“We're not exactly, like, GIT kind of guitar players."

The man is Mark Arm. The question he's answering: How is it that, over the course of his and co-guitarist Steve Turner's 30 years in legendary Seattle garage-rock revivalist outfit Mudhoney, they've been interviewed by a guitar publication exactly once … 27 years ago?

Think about that. This is a band that didn't just help lay the groundwork for the Pacific Northwest's “grunge" scene as it shared bills both stateside and abroad with movement heavyweights like Soundgarden, Nirvana, and Tad. No, this is a quartet that the founder of the now-iconic Sub Pop label, Bruce Pavitt—who signed Mudhoney in 1988, as well as all of the aforementioned bands—touted as the label's “flagship" band. In a 2012 interview with Paper, Pavitt even admitted that, before Nirvana became a household name, Cobain and company were like Mudhoney's “little brother." Asked what he thought the first time he saw frontman Arm, Turner, drummer Dan Peters, and original bassist Matt Lukin play one of their notoriously ferocious live shows, Pavitt replied, “I thought they were one of the greatest bands in the history of rock 'n' roll!"

And yet, when PG dials up Arm and Turner to talk about Digital Garbage, Mudhoney's 10th LP since their explosive '88 debut EP, Superfuzz Bigmuff—an album that literally wears its gear proclivities on its sleeve—neither seems to hold a grudge about the three-decade snub. While the former briefly quips about the contrast between the Mudhoney 6-string way and those at the '80s shred temple formerly known as Guitar Institute of Technology (today's Musicians Institute), the latter hardly seems to have noticed.

But anyone who knows Mudhoney knows that's simply their way. They've weathered 30 years in a messy business without any breakups or artistically dubious reunions precisely because they don't give a shit, much less two, what anyone thinks. And that's not because they're dicks—although Arm in particular is known for silly antics (in the between-song banter on live tracks from the deluxe edition of Superfuzz, for example, he bids Berliners “howdy," mimics JFK's “Ich bin ein Berliner" line, and tells the crowd to “pull down your pants if you like us"). The simple fact is they're just a bunch of low-key, practical friends having a good time doing what they love. They know what they like, and that's what they do. Hell, even when they're being complimented for the huge influence their raging Mustangs and Hagstroms have had for the last 30 years, they'll demure with some anecdote about how, when people toss around the L word—“legends"—it's merely code for “not dead yet."

Even so, a closer look at both Mudhoney's music and the things they say and do reveals a lot more nuance and, yes, growth. The passing years and fads have, thankfully, never inspired embarrassing stylistic jumps like the ones that cause Arm to wince on behalf of former heroes Aerosmith. “Fuck—'Janie's Got a Gun' … Armageddon [“I Don't Want to Miss a Thing," recorded for the 1998 Michael Bay movie]?! I'm glad they're all still alive, but if they'd just kind of broken up when they originally fell apart, it would've been much better," Arm says. But Turner, who now resides in Portland, and Arm, also aren't interested in putting out the same album over and over again. As their catalog of 10 LPs, five EPs, and six live albums attests, Mudhoney has evolved the way a stable, well-adjusted friend might grow over time: New experiences, knowledge, and circumstances leave their inevitable marks, yet they never succumb to insecurity and lose what made you love them in the first place.

And, frankly, that's because, well, the guys are great friends. Their time together doesn't just go back to '88. Turner and Arm have been pals since the end of high school, when they played together in a band called Mr. Epp and the Calculations. Two years after that, in 1984, they formed Green River with guitarist Stone Gossard and bassist Jeff Ament, both of whom would go on to worldwide fame in Pearl Jam. And even though Lukin (who, prior to joining Mudhoney, co-founded Melvins with Buzz Osborne in 1983) eventually left in 2001, replacement bassist Guy Maddison has been aboard going on 18 years now.

2018's Digital Garbage showcases Mark Arm's wickedly sharp tongue that has been wielded not just for laughs but also to draw blood on some pretty heavy social and political issues.

Arm, Turner, Peters, and Maddison, also take time out for other friends and projects without letting it bug each other. And as they've matured in years, the subject matter of Mudhoney songs has gotten more thoughtful, too. Arm's penchant for a good time remains, but as the 21st century has progressed, his wickedly sharp tongue has been wielded not just for laughs but also to draw blood on some pretty heavy social and political issues—as evidenced by the 11 unflinching tracks on Digital Garbage.

Here, Arm and Turner discuss a host of subjects, from how their latest effort was scrapped and overhauled after the events of November 8, 2016, to how Arm, 56, keeps his voice sounding like it did 30 years ago, and whether, in the age of boutique fuzzes, Super-Fuzzes and Big Muffs still rate No. 1.

Let's start off talking about the new album: Between the title, Digital Garbage, and song names like “Next Mass Extinction," “Prosperity Gospel," “21st Century Pharisees," and “Kill Yourself Live," is it fair to say it was more motivated by the state of the world than some past efforts?

Mark Arm: You know, what's going on in the world has always been in the background, but I think the situation became so acute that I just couldn't write about girls and cars or whatever [laughs]. I grew up in punk rock, and hardcore in particular, and some of my favorite bands at the time were super political—like Crass, Discharge, the Dead Kennedys, and Really Red. For a while there I thought, oh, we don't need to play “F.D.K. (Fearless Doctor Killers)" [from the 1995 album, My Brother the Cow] anymore, because you don't really hear about abortion clinic bombings. It kind of comes and goes in waves.

Politically, things are obviously quite different from when your last album, Vanishing Point, came out in 2013. Did that end up being more of a motivator to make these lyrical statements than it had been in the past?

Arm: Well, we had been working on stuff earlier, but we went back and listened to what we'd done and decided it didn't really live up to the standards, musically. We had three or four songs we'd written around 2015, 2016. We were going to start working on a record in 2016, but Steve and I got sidetracked doing a bunch of stuff with Monkeywrench [a bluesy project with Poison 13 guitarist Tim Kerr]. In a way, I was going, man, I can't wait for all this [2016 U.S. general election] campaigning crap to be over so I can concentrate on writing a normal record.

Assuming things would turn out different from how they did….

Arm: Yeah! It would just be the usual kind of inter-party bickering. Hillary Clinton would win and the Republicans would do “Benghazi! Benghazi! Benghazi!" or whatever … same old shit. But things obviously took a step—in my mind anyways—in an insane direction.

These days Turner (shown here still proudly touting his anarcho-punk roots with a vintage Crass T-shirt)

is mostly seen with one of his late-'60s Guild Starfire IVs. Photo by Tim Bugbee

Did that make you guys work harder and kind of focus you?

Arm: I guess it kind of focused me lyrically. But, ideally, it's not the record I wanted to make, if that makes any sense.

Steve Turner: Every day that he brought in another song with lyrics was pretty mind-blowing to us. We were like, whoa! For example, “Please Mr. Gunman"—I swear that was two days after the church shooting in [Sutherland Springs] Texas. Some Fox News commentator, I think, said, “Well, at least they died in church." Mark had those lyrics done by the next practice.

So, in an alternate reality these same riffs would have completely different lyrics?

Arm: Oh yeah. Although a song like “Night and Fog" [which hints at the horrors of a nighttime ICE raid] probably wouldn't have been written at all. I guess that's a good or a bad thing, depending on how you view that song.

How does the writing process typically go for you guys—and has it changed much over the decades? Like, since Steve lives in Portland now, do you send each other song ideas?

Turner: No. I thought we would start to do that a little bit more, but there tends to be an order of how we work.

Arm: We tend to do things in person. Generally we come up [to Seattle] for practice once a week, if we're on a roll. When we were writing [for Digital Garbage], Steve would sometimes come up and stay for two practices in a row, which is really helpful, so you don't forget what you just did the night before.

Turner: Mark really likes to be in the room and jam out together, which I understand. He wants it to be a group collaborative kind of thing. I think he feels weird bringing in a whole finished song. We love it when he does—it happens occasionally. He'll have something totally put together and we'll bend or morph it into something else. But, generally, someone has an idea or two for a verse. And then we have this little digital recorder down in the basement that Mark's got a lot better at recording on…

—Steve Turner

Arm: We have a digital recording device now, so we're almost current in technology! [Laughs.] We've got this 2005 Korg with a hard drive and a CD burner. To get the music out of there, you've got to burn it onto a CD and bring it up to my computer.

Turner: Usually we just throw some riffs together and jam on them for a while … put them in some sort of order so that Mark has them to listen to and try to put some lyrics and melody to.

A lot of influential bands that have been around as long as you guys have end up struggling to evolve their sound—and often fail pretty miserably. Yet, with each new album, you guys manage to sound instantly identifiable but also genuinely fresh and inspired.

Arm: Oh, that's a great compliment. I don't feel like we're looking for a new sound. We are who we are, but we're not afraid to … as much as I love, like, the Ramones and Motörhead and AC/DC, we're not just throwing out the same kind of riffs every time.

How do you pull that off—is it just a matter of being comfortable in your own skins and not giving a shit what anyone thinks?

Arm: I think probably just not giving a shit what other people think. Obviously we take great care in what we do, and we love writing songs and recording and playing. But we're also not too precious about it. When we go in to record, we don't spend weeks on just one song. We record pretty quickly. Usually everything is pretty well worked out, except for maybe some weird overdubs. Over the years we've learned that usually the first idea is the best.

Turner: We have a small wheelhouse. It's the four of us, and we do what we do. We're not trying to keep up with anything—or even pay attention to anything—but we do expand. There's always something that each one of us is super turned-on by recently. With Mark's lyrics, it's the world. And there are always weird musical elements that will pop in—like, Guy [Maddison, bass] is totally into synthesizers right now. That showed up on this record, which was great. And Dan [Peters, drums] is playing a lot of guitar lately, so we kind of told him that he had to bring in a song for us, which he did. There's always a little twist.

Guitars

'67 Guild Starfire IV

'68 Guild Starfire IV

Circa-1971 Fender “Competition" Mustang

Amps

1965 Fender Super Reverb

Fender Hot Rod DeVille 410

Fender 1965 Deluxe Reverb Reissue

Effects

DOD Overdrive Preamp 250

DOD YJM308 Yngwie J Malmsteen Signature Overdrive

Electro-Harmonix Nano Big Muff Pi

Foxx Tone Machine

Foxx Fuzz Wah Volume

Ibanez TS9DX Turbo Tube Screamer

MXR Micro Amp

MXR '74 Vintage Phase 90

Vox V847-A Wah

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball .010–.052 string sets

Jim Dunlop .73 mm Tortex picks

Let's discuss some of those “twists." “Messiah's Lament" is somehow both kind of raucous and laid-back, with kind of a Neil Young vibe.

Arm: That was the song that was brought in pretty much top-to-bottom by Dan. It kind of reminds me of that song “Round & Round" on [Young's second 1969 LP] Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere.

Turner: It's a very different style of guitar playing. I think it's pretty amazing when drummers start writing songs on the guitar. They always have really good rhythm, so they're already one step ahead of most guitar players.

Arm: Dan's spent probably the last 10 years—ever since he was a stay-at-home dad taking his kids to school—really learning guitar on acoustic. He knows chords that I don't know!

Did Dan play on the album version?

Arm: He showed Steve the riff, and Steve played it. Then Dan had a bunch of 12-string overdub ideas, I think.

Turner: His take on rhythm was totally different from mine. It was kind of a challenge to learn how to play.

“Kill Yourself Live" has some really interesting country-ish slide riffs.

Arm: When we started jamming on that, the way Steve was playing the guitar chords—sort of open-chord picking but strumming at the same time—kind of reminded me of “Gut Feeling" by Devo.So we decided to construct an intro that pays homage to that. Before we practiced it with organ, I played slide guitar to do something that would fit but sound different. I think it's the only slide guitar on the whole record.

The jam at the end of “Prosperity Gospel" is pretty glorious. And, considering how fired-up the lyrics are, it's surprisingly lovely and melodic, too.

Turner: If anything inspired that, it's the guitar playing from “Eight Miles High" by the Byrds.I think [Byrds frontman Roger McGuinn] was trying to be like [jazz-sax great] Pharaoh Sanders for some of that really crazy 12-string stuff he did. I tried to do it on a 12-string, but I couldn't get anything happening.

What did you end up using instead?

Turner: My regular Guild Starfire IV. I have two red ones, a '67 and a '68. I believe it's the '68 that's better to me. It's a little heavier, it's got better tuning pegs, and it's got a slightly bigger neck.I have a Starfire 12-string, but I just couldn't get the soloing sound I wanted at all on it.

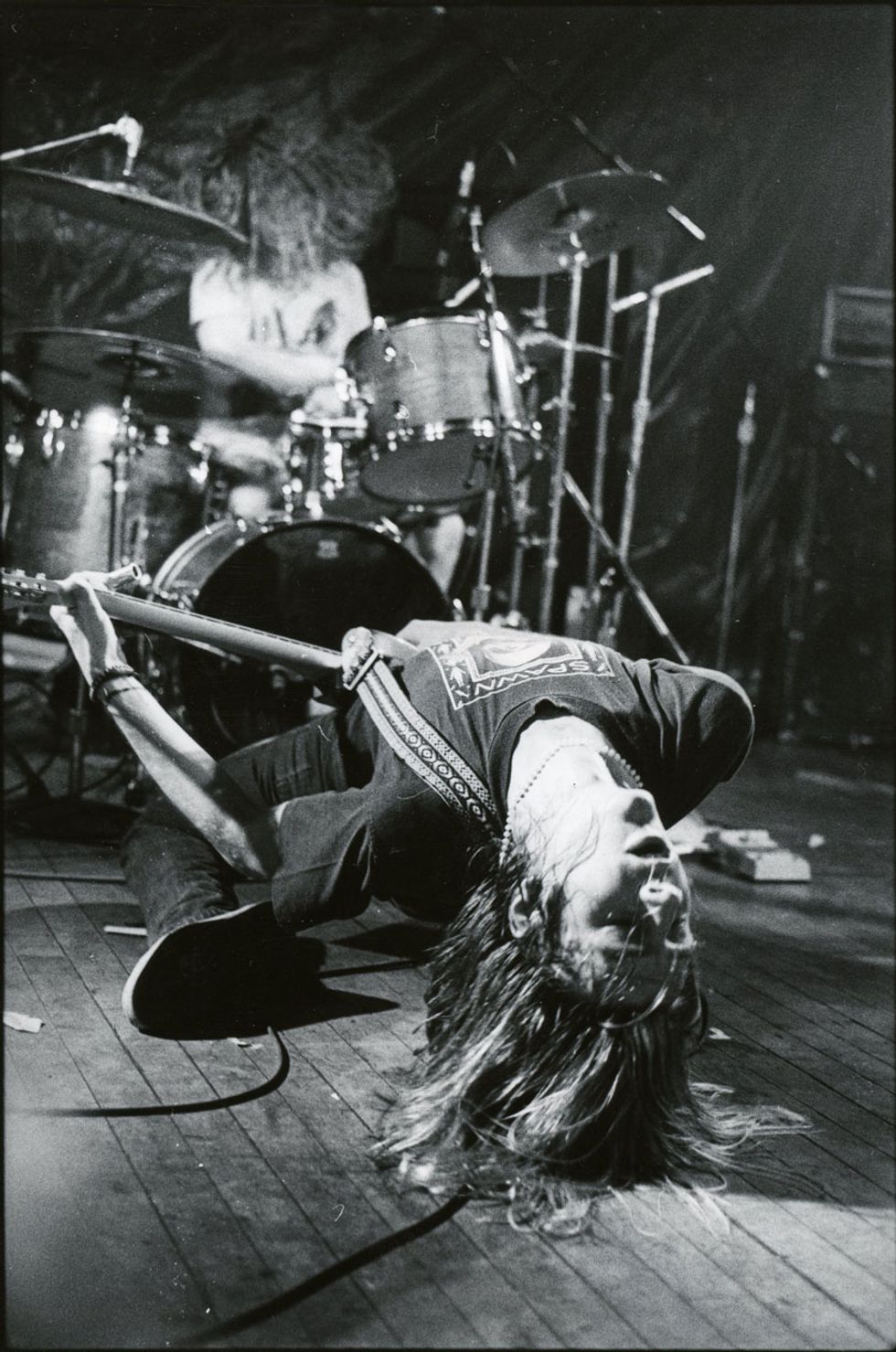

Arm bringing down the house at an April 1993 gig in New York City. Photo by Frank Forcino / Frank White Photo Agency

“Prosperity Gospel" also has a really live feel. Was that all from a single take with the whole band?

Turner: I think so. I tried to do other stuff, and then we just kind of decided the live take was the best. Generally, for it to be a keeper for a basic track, Dan, Guy, and myself have to have a good take together live. There might be a couple tiny fixes on bass or guitar, but for the most part it's got to be a good live take for all three of us. Almost all, if not all, of my main guitar tracks on the record are live. Usually Mark has to redo his guitar, because we don't know the songs very well yet and he's guiding us through a lot of vocal cues and can't concentrate so much on the guitar.

Do you guys try to keep up on gear developments at all?

Arm: Yeah, not so much.

Turner: Not really. A lot of people give me fuzz boxes, and different companies will hand me stuff. Like Tym Guitars in Australia makes some amazing Big Muff and other related clones that I think are fantastic. So there's a few companies like that I keep up with—Death by Audio's Fuzz War was a pretty amazing pedal a few years back.

Arm: Oh, we'll try new pedals. In the '90s I was trying a whole lot of different pedals—I've got a shelf full of things that I never use, things that I would buy and play in the store that sounded cool to me at the time but I never really found a place for. My setup is pretty minimal.

Turner: The first song we actually got done for this record was “Hey Neanderfuck," and I was trying to get as heavy and gnarly a sound as I could. There was this textured pink box this guy gave me—it didn't have a name on it, so I can't say what the company is, unfortunately. There's definitely some [Univox] Super-Fuzz in there, but there's also an octave button. It made that riff. But I always have an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff in line. My favorite is the Nano, the cheapest ones they make.They're like $60 or something. They're almost disposable—because they do break. But oh, well. Buy another one!

We're just old at this point!" —Mark Arm

You guys are obviously huge fuzz connoisseurs—you named your debut album after the two you just mentioned, Steve—but it's interesting that the Nano Muff remains your favorite at a time when there are so many painstaking boutique clones of vintage fuzzes fetching pretty serious money.

Turner: I'm kind of trying to get the sound of my original Big Muff. The one I used on all of the earlier records is one of the last production Big Muffs, I think. I got it new in 1984 on closeout. Going off memory and feel, to me the Nano sounds the most like that. In the studio I bring in a whole bunch [of other fuzzes], but then sometimes I just get lost trying to fix something that doesn't really need to be fixed, you know what I mean? There are others, though—the Foxx Tone Machine. I used to use the Foxx Fuzz Wah Volume quite a bit. That's one of the best fuzzes ever made, and the Tone Machine is basically the fuzz side of that. I always have that one in the studio with me, but I didn't use it on this record.

If you think about the aesthetics of where we come from—garage punk, and punk rock in general—a lot of it was made with cheap gear, and a lot of it was reclaiming gear that guitarists had kind of dismissed as garbage. Like the Mustang. That was my ultimate guitar back when I was a kid, but it was pooh-poohed when I finally got one. I could get them for $150. The Danelectro and Silvertone amps were kind of high-rated garbage when we were getting into them. We based a lot of our sound on cheap gear, so it makes sense to me that I still buy the cheap gear.

Arm: In the '90s one of the boxes that I landed on that I liked most was this Ibanez Soundtank-series 60's Fuzz. I think they only made it for a year or two, because they're made of this cheap plastic—they look like a little black Volkswagen Beetle—and they just break. Anytime I'd find one in a music shop I'd just buy it and have a buddy put the guts into a metal box.

Guitars

Gretsch G6129T-59 Vintage Select '59 Silver Jet

'60s Hagstrom III w/Filter'Tron neck pickup (tuned to open A for slide)

Amps

'70s Fender Super Six Reverb

Effects

DOD Overdrive Preamp 250

Ibanez Soundtank FZ5 60's Fuzz

Moog Minifooger Analog MF Delay

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball .010–.052 string sets

Jim Dunlop .73 mm Tortex picks

Peterson pedal tuner

Before we close, Mark, I wanted to ask how you keep your screams and howls sounding so consistently feral all these years? It's a wonder your voice isn't shot!

Arm: I really don't know. I mean, it might somehow be genetic. My mom used to be an opera singer, so she had a pretty strong voice … but she didn't scream. I never had vocal lessons or anything, but the one thing she told me was to sing from your diaphragm. I don't just sing through my throat, it comes from a deeper place. Maybe that has something to do with protecting my vocal chords. Now that I'm a little older, it takes a couple of practices to get it in shape for a show. If we're on tour, as long as I don't get sick and we get enough sleep, then it's fine. Getting enough sleep is key. When we first started touring, I had no concept of that.

Last question: Mark, in an interview a few years back you were asked whether it was weird to have big music magazines fawn over you guys when you first went abroad in the late '80s. You talked about the importance of being confident—even if it's false confidence—in order to keep getting onstage night after night. Now that you're regarded as legends, has that aspect changed at all?

Arm: You know, I still get nervous before we go on. I don't know if that has anything to do with confidence. It might just have more to do with caring rather than just going through the motions. We're all confident in what we do and how we work together and how we play together. And I'd be hard-pressed to actually believe we're legends! We're just old at this point! In the mid 2000s we played a show with Motörhead in Portland. Afterwards, we met Lemmy [Kilmister, late bassist/vocalist]. A couple weeks later, Steve and I were traveling to the U.K. We were in the same immigration line as Lemmy, doing that zig-zag thing. At one point he just says, “You know, all you've got to do is stick around and they'll start calling you a legend."

That's a lot easier said than done!

Arm: I guess it depends. For us it might just be a case of inertia. What else are we going to do? The ball's already rolling. We like each other a lot. We get along. We love what we're doing. Why stop, even if no one gives a shit?

Step into a time machine via a treasure trove of vintage footage showing crowds moshing, headbanging, and stagediving to Mudhoney's fuzzed-out, relentlessly energetic 1988 debut single, “Touch Me I'm Sick."

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)