The music of Colombia’s Los Pirañas imagines an alternate universe where traditional sounds meet the futuristic. Pulling in listeners with rhythmic and melodic elements drawn from cumbia and other Latin American styles, guitarist Eblis Álvarez infuses the band with a heavy dose of high-tech, glitched-out sonics. This signature formula creates a frenzy of pulsating grooves built on a bed of Latin percussion, throbbing bass, and whacked-out guitar riffage that leaves listeners’ heads spinning.

While the boundaries created by traditional musical forms can be restrictive, they can also provide a framework for experimentation. Los Pirañas exists as part of a lineage of Latin American music that has thrived by using creative developments in guitar technology to explore within those boundaries—just like the Peruvian guitarists who were inspired by surf music and brought the electric guitar to folk styles, or those who combined psychedelia with traditional cumbia in the 1960s and ’70s.

Drawing on his background as a classical composer focused on electro-acoustic music, Álvarez uses Max MSP programming in conjunction with a modest pedalboard to create his signature sounds. High-tech guitar rigs are nothing new, but it’s the way Álvarez uses these tools that is so novel. Over the course of the band’s three albums, starting with 2012’s Toma Tu Jabón Kapax, the guitarist has dived into the deep end of tonal experimentation while injecting a heavy sense of humor and absurdity into his sound.

This sensibility is typical Álvarez. As the founder of the wildly eclectic Meridian Brothers, he has kept busy exploring the combination of technology and a variety of traditional Latin American styles, creating a prolific body of work, since starting that project in 1998. Despite the band’s name, Álvarez composes, produces, and plays many of the instruments on the Meridian Brothers albums himself.

Los Pirañas, on the other hand, is a collaborative that thrives on the relationship between Álvarez and his bandmates: bassist Mario Galeano and percussionist Pedro Ojeda. Though Los Pirañas didn’t form until the 2010s, the band has a much deeper musical history that goes back to the 1990s, when the three musicians started jamming as teenagers. In the time since, they have worked on various projects together, with both Galeano and Ojeda appearing on Meridian Brothers recordings, and they’ve developed a musical sensitivity and responsiveness that seems almost telepathic. Over the course of Los Pirañas’ three full-length releases, they’ve tracked the development of their improvisation-heavy collaboration. Historia Natural, Los Pirañas’ new album, finds the trio once again expertly handling rhythmic and dynamic changes at explosive energy levels as they kick out 10 tracks of tropical oddities, such as the bouncy “Llanero Soledaño” and the avant-surf-ish “Palermo’s Grunch.”

Wanting to learn all the fascinating details behind Álvarez’s work with Los Pirañas, PG recently caught up with the guitarist on Skype shortly before the band kicked off a European tour.

You’ve been playing with the other members of Los Pirañas for a very long time, but when did the band form?

The story is that Mario, Pedro, and I … we have different projects. Mario’s very into collecting records. Mostly Colombian records. Pedro is also into collecting records and he’s into all sorts of percussion combinations. He’s like a researcher for drummers—any kind of a percussion tradition between Africa and Latin America. I’m very into computers and programming, and synthesizers and composing. We’ve been friends since high school, when we used to get together and play, although we have had our own projects.

The beginning of the band was, Pedro had a gig and his musicians canceled on him. He called us and we began to play at a restaurant, trying to be ambient music for the diners. He asked us to not be too noisy or too experimental. We were playing boleros and we were playing jazz music in a bolero fashion. But then I started playing with all sorts of pedals, very soft, and it worked.

We began to be hired to play parties, improvising our stuff. After throwing five or six parties, a label here called Festina Lente [which translates as “make haste slowly”] told us, “Hey, you guys need to make a record.” So we went to the bar where we play experimental music here [in Bogotá]—it’s called Matik Matik—and we brought this portable studio and recorded the very first record based on this material. By then we got fired from the restaurant because we were too noisy.

How do you compose material for Los Pirañas? Obviously there’s a lot of improvisation, but there’s riffs, great melodies, and changing time signatures.

We work in two layers. The first layer is Pedro and Mario. They are really interested in all sorts of African and Afro-Colombian rhythms, and they have a connection together. They look to each other and change tempos and do accelerandos and Mario screams at Pedro and they change. They don’t know what they’re going to do, but they do it at the same tempo. They are very together.

I jump into that and I do all my computer patches and pedal experiments. Sometimes I propose something and they follow me. Sometimes I just get surprised that they change and I don’t realize it. And it works like that.

TIDBIT: Los Pirañas albums—including their latest, Historia Natural—begin with improvisations, which are then whittled down into individual riff-driven songs. “We just do riffs, riffs, riffs,” says Álvarez.

Are you saying that the albums aren’t composed songs, they’re just improvised?

Yeah. We begin to improvise and then we say, “Oh, that sounds good. So let’s try to polish it.” But it’s just improvising. It began to work like a kind of jazz music: you have a theme and then you improvise. But of course, we don’t do solos. We just do riffs, riffs, riffs.

You need to have a really good connection with each other to pull off something like that.

We share a taste for records, for Colombian music, for all the lines of research we’ve been doing through the years. We rehearse once a year. When we do the records, we just meet at the studio or, this time, at this bar, and we just play, play, play, and then we choose the better recordings so we can learn it.

You’re about to go to Europe on tour. Will you learn the music off the album or improvise live?

We have to learn to put together the riffs. You put out a record and people want to listen to the tunes they are used to. Of course, we will still do our usual improvisation.

The band’s sound is so focused, and it sounds like you’re playing tunes.

We were jazz players in the ’90s. At some point, we got tired of that, of jazz or even free jazz, and we got into traditional music. Pedro got into afrobeat, Mario got into Colombian cumbia, so after a while, we just left jazz. I don’t play jazz anymore, but I think we kind of remain in that attitude towards music. “Let’s jam.” It’s like that. But, of course, in this two-layer improvisation system, we don’t jam like it’s jazz. We work with traditional melody. Cumbia, for example, Peruvian traditional melodies, Colombian traditional melodies. The rest is noise and rhythm.

How does Los Pirañas relate to traditional music? What are you drawing on?

Everything goes through some part of the traditional music, starting with Pedro, because he has this set of drums that is kind of nonconventional. Instead of tom-toms, he uses timbales. He has cowbells and he has a double hi-hat in order to make all the traditional polyrhythms. He has developed a very special way of playing by combining several drums from different traditional musics.

Our main basis is the traditional cumbia, but also orchestral cumbia and guaracha. Pedro is also very in touch with all the African traditions, like soukous, highlife, afrobeat, and he actually joins everything into his style. Mario jumps in with mostly a cumbia basis.

My departing point is the Peruvian guitarists. Peru is the more developed country in terms of electric guitar and tradition. They really developed a huge style—Manzanita, Enrique Delgado, Juaneco y su Combo, Los Mirlos, Los Ecos. There are tons of bands playing with electric guitar and they got that from surf music. It’s a whole historical development of the guitar in Peruvian music. Unfortunately, it didn’t develop enough in Colombia.

Álvarez says Los Pirañas works in two layers, with bassist Mario Galeano and percussionist Pedro Ojeda creating a bedrock of shifting rhythms while he lays sometimes radically unpredictable guitar lines on top. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano

The bands you mentioned are older bands, from the 1960s or ’70s. So you’re being influenced by this older music and pairing it with modern guitar sounds, turning it into this futuristic version of the past.

As a jazz guitarist and rock guitarist, I jumped into that older music in order to build a basic style, and then I put something abstract in it, which is the elements that come from computer programming. I am very into electronic music, but more in an abstract way—not in the social or cultural way. I’m not playing raves or parties or being a DJ. I’m mostly into programming sounds with computers. And so I just combine both.

How did you get into programing?

I studied composition. In the 2000s, I was into electro-acoustic composition and I was more like a classical composer. I studied classical guitar. I’m a trained classical musician. I still compose pieces for orchestras and ensembles, but not that much compared to the work with the bands.

In classical school, I learned to do all sorts of electro-acoustic music, programing, interactive installations—all kinds of soundscape techniques and composition. I studied that in Denmark and I was living there and doing all that stuff, but, at one point, I realized I could join all this electric guitar stuff with the signal processing and synthesis I was working with.

Tell us a bit about your process.

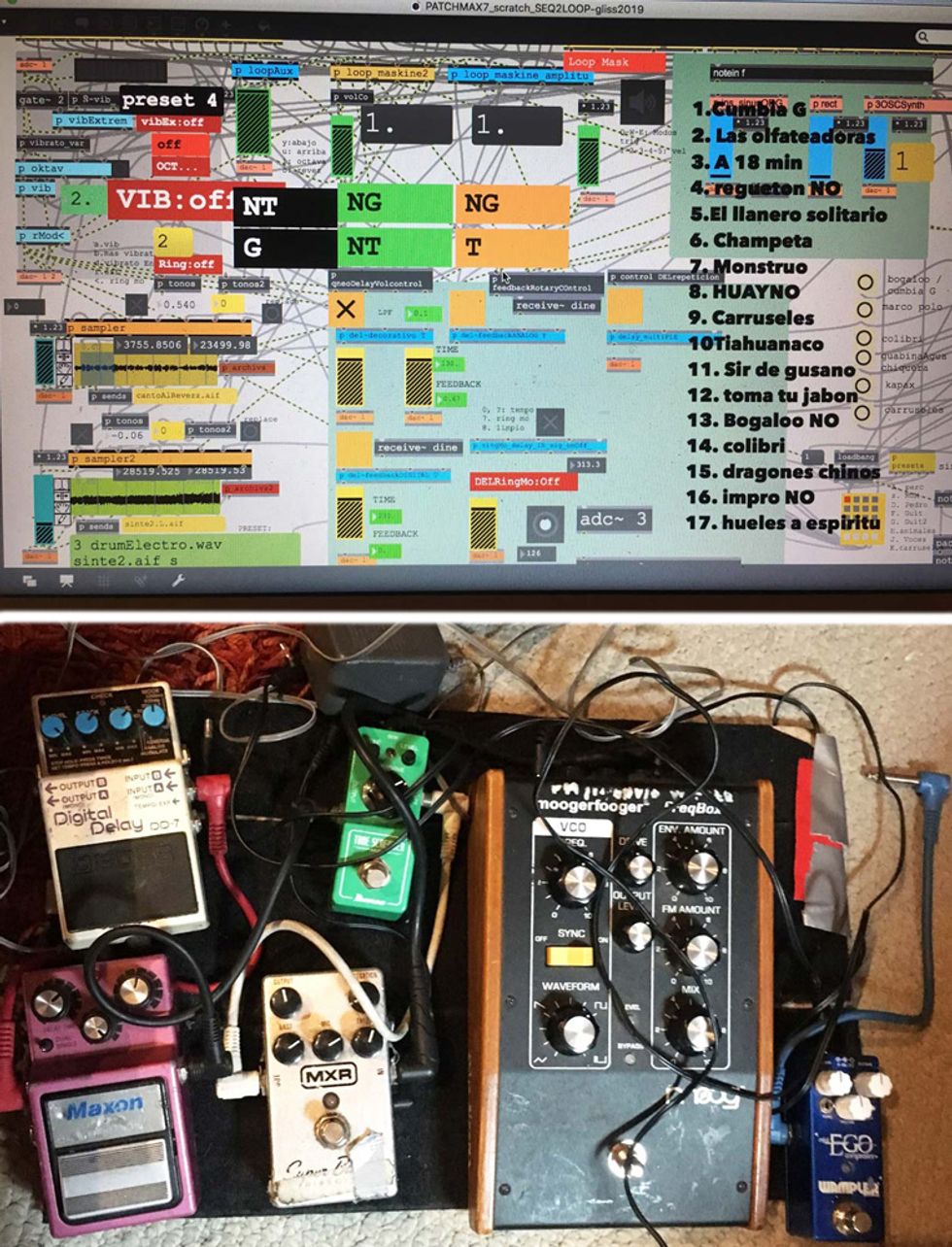

I program in Max MSP. There are three lines of electronic music: signal processing—all the ways of processing the signals; synthesis, which is the way to produce signals electrically; and sampling, which is recording of all those signals and playing them back together. The ramifications are infinite, but studying these three techniques, you can start to build your stuff in whatever means you want, so I experimented with everything.

Guitars

2000s Fender Jaguar

Amps

Fender Deluxe Reverb

Effects

Max MSP

Boss DD-7 Digital Delay

Ibanez Tube Screamer Mini

Maxon AD-9 Pro Analog Delay

Moog MF-107 Freq Box

MXR M75 Super Badass Distortion

TC Electronic Shaker Vibrato

Wampler Mini Ego Compressor

Strings and Picks

D’Addario (.012–.054)

To be simple, I just have tons of signal processing patches into Max. I just alter amplitude, frequency, and phases. These are the three things you can alter. I’ve built several processes into these three functions. Then I go to pedals. I use the pedals because some pedals sound much better than the computer—mostly distortions and some delays that have a particular sound. But everything is pretty much common stuff. There is nothing weird on my pedalboard.

When I see people using Max to process their guitar signal, they’re usually making noise music or ambient music, and the guitar ends up being this really expansive thing. You don’t hear it much in a more groovy, note-based setting.

People usually think that those programs are made for noise, for massive atmospheres or sound art, but you can be very simple with those programs. This is the beauty of it for me. You can just get an oscillator and make it do something that your imagination puts into it.

Since we are working a lot with traditional music, there are a lot of melodies. The melody is very important for us. Noise music is something foreign to traditional music, unless it goes into the percussive layers. So I just put the noise into the rhythm and put it in a role that fits with traditional music.

What is the order of operations in your rig?

I’ve tried everything, but now I do guitar, computer, and then pedals. Sometimes, if I have enough room or enough cables, I do a split and I put the computer in the middle of the rig in order to be able to process the first part. For example, when I’m sampling the guitar live, maybe I want to sample some part of the processed pedals and then have the sampling being processed by the pedals afterwards. I’ve tried everything. On tour I go with the simplest things, but in Bogotá, when we play, sometimes I do small experiments. I’m always changing.

What kind of amp do you usually use?

I’m not very specific about amps. I just have shitty amplifiers. I don’t bother with that. I just play with whatever I get. But through the years my favorite is the Fender Deluxe—the reissues or the old ones—because they have a lot of attack. I’m very obsessive with attack because we play so rhythmically.

How do you differentiate between this band and the Meridian Brothers?

I really try to put each band in an independent drawer, because it’s very dangerous to end up mixing all the styles. Right now, I have four bands, so I’m very into separating those styles.

Los Pirañas is very guitar-oriented, and I’m trying to get the guitar into all kinds of boundaries I can cross. Meridian Brothers is mostly a composer project, experimenting with different cultural clichés of mostly Latin America. Recently, I’ve been doing a kind of punk-style salsa. Then I have Chupame El Dedo, which is a kind-of satanic metal band with synthesizers. And I put out a new project, El último Meridian, that is mostly like reggaeton, trap-oriented. I divide a lot and I really try to put a wall between the way I approach composition and styles.

The guitarist’s signal chain runs through both a laptop using Max MS software and a modest pedalboard that always includes an Ibanez Tube Screamer Mini, a Maxon AD-9 Pro Analog Delay, and a Moog MF-107 Freq Box, among other goodies.

Describe the scene you’re a part of in Bogotá.

It’s a small scene with tons of bands, concerts, and parties. For me, the good thing about it is we are enclosed. Sometimes it gets too much enclosed, but the good thing is that it is a kind of a feedback loop of musicians and artists doing parties every weekend, two or three times a week. For me, it’s healthy.

We used to have very healthy local record industries. We had a lot of presses and record labels that were doing local music. It was sold locally. But in the ’90s, everything was destroyed. Everything was global and now it’s even worse. We don’t have a healthy economic music industry here. We have to go outside. We have to go to Europe or to the U.S. to play. You cannot live off of music. If you are a teacher, you can. But you cannot sell your records. You cannot get royalties. Concerts don’t pay well.

We are exposed to globalization or standardization. The taste that is developed is a taste that belongs to cultural development. People here sometimes refer to the global icons of the music industry, such as Pink Floyd or Nirvana or whatever. But small collectives are putting music out and throwing parties. They are very into a taste that developed in the last 15 years, which is a combination between global influences and people looking back to musicians such as Pedro Laza, a very traditional, important musician here, or Andrés Landero, or whatever. The references are this local taste instead of the global standardized icons. That makes things rich. People are dancing to champeta, to reggaeton, to cumbia, to salsa—and that's cool. These small collectives are talking through their own blood, not through standardized icons, which the big industrial complexes of music are trying to do.

Los Pirañas dish out a high-energy helping of tropical grooves and weirdo guitar tones in this live Mexico City performance from 2016. Check out the wild animal sounds that Eblis Álvarez coaxes out of his Fender Jaguar at 2:08 and 3:17.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.