Guitarist Buck Curran embodies the spirit of folk music as much as he plays in that style. He grew up in Ohio, and he’s lived in Ireland, where he absorbed the culture of his heritage, and in Virginia, where he worked on folk instruments and became immersed in sitar music, and then in Maine, where he started the psych-folk duo Arborea—which recorded six albums—with his then-wife, Shanti.

It was during his time in Virginia that Curran started developing his own voice. Driven by the desire to capture the contemplative drones of ragas and replicate the timbre of the human voice on his 6-string, he began to explore an East-meets-West acoustic guitar style. He was later inspired to produce two tribute albums to one of the genre’s leading figures, Robbie Basho.

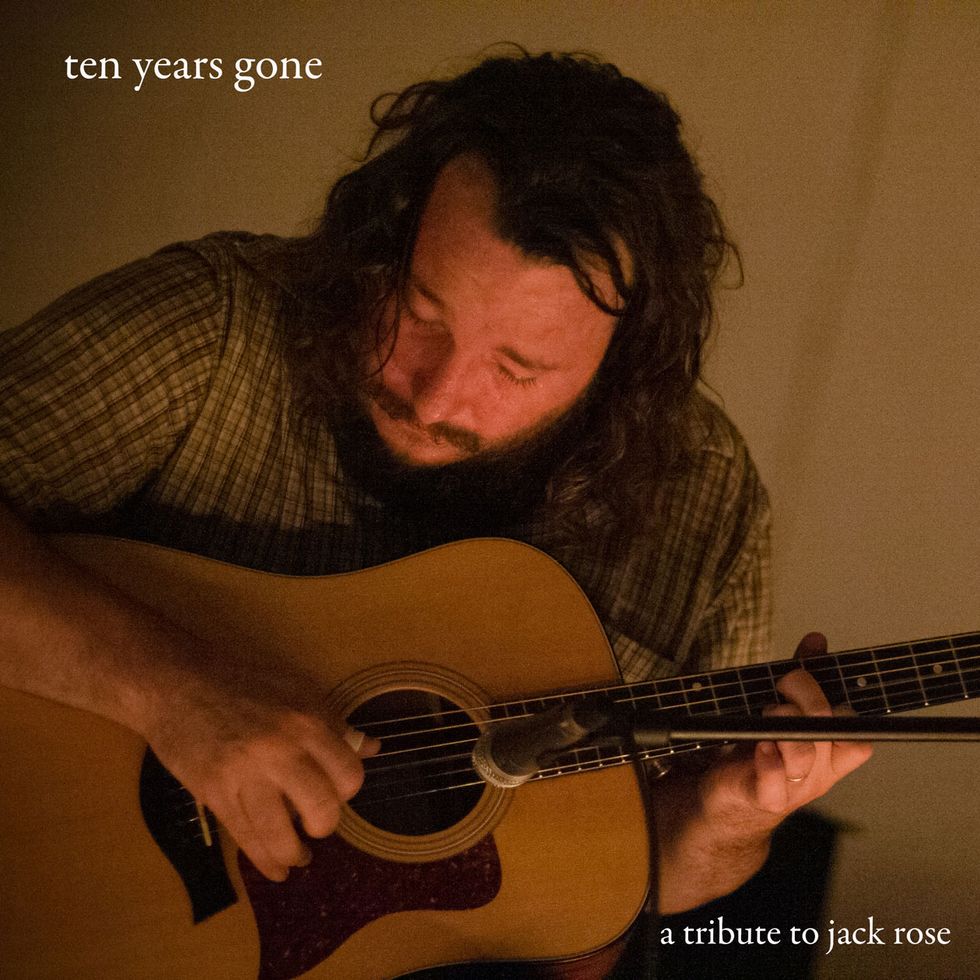

Following suit, his latest project, Ten Years Gone: A Tribute to Jack Rose, is an homage to Rose’s contributions to what’s become known in recent years as American primitive guitar. Originally a member of noise/drone band Pelt in the early ’90s, Rose discovered a passion for the fingerpicking and textural styles of John Fahey and Robbie Basho in the early 2000s, and the self-taught stylist dedicated the rest of his prolific career to this music until he died from an apparent heart attack on December 5, 2009.

Hear Buck Curran play “Greenfields of America,” his slide guitar contribution to the new album, Ten Years Gone: A Tribute to Jack Rose.

Curran’s idea was to release the tribute album—which he’ll follow with his own just-recorded solo release, No Love Is Sorrow—on the 10th anniversary of Rose’s death. He scrambled to compile the work of 13 different players over the three months leading up to that anniversary. They include Mike Gangloff, a former Pelt member, and Helena Espvall, who has recorded and played with Arborea, Bert Jansch, and Vashti Bunyan. With all those different voices, the album is still unified by the same romantic, folkloric spirit, weaving from sonorous cello to twanging ragtime guitar to the droning acoustic palettes that were the signature of Rose’s style.

When I spoke to Curran over the phone at his home in Bergamo, Italy, our conversation touched on Rose very little. Curran was eager to share his musical life stories and how a global ancestral voice is expressed within the genre the album celebrates. A lot of his interest lies in reproducing other instruments, not just voice, on the guitar. He comments on one of his favorite piano pieces by Robbie Basho, “Rhapsody in Druz,” which sounds as if played on the Persian dulcimer-styled santor, which in turn reminds him of Debussy recreating the sound of gamelan on piano. He says how the appearance of the Turkish ney—an end-blown flute—on Peter Gabriel’s soundtrack to Passion made him think, “How do I do that on guitar?”

Curran is a great conversationalist, with plenty of oral history to share in a vein that speaks to a greater community of players. Just listen.

How did the idea for the Jack Rose tribute album come about?

It goes pretty far back, to Arborea’s second album, while Jack Rose was still alive. I did a composition dedicated to him, and then, in 2009, he passed away suddenly after he got off tour. Over the years I thought about re-recording that, because that particular instrumental was improvisation, so it was pretty raw. And up to about a year before the 10th anniversary of his death that just happened in December, I was still kind of mulling over that idea—to release it as a single, as a tribute to him. But I suddenly realized, because I’ve done these tribute albums to Robbie Basho—who was also an influence on Jack Rose, and was informed by Japanese music and Indian music ... I worked with so many great guitar players for those two volumes that I thought it would be better to do the tribute as a community. There wasn’t a lot of time at the point I decided to start asking people.

How do you know all the musicians on the album?

I had to really think about who were Jack’s friends. For years, Sir Richard Bishop was in the Sun City Girls. His music is influenced a lot by Gypsy music. Around 2010 or 2011, Rick and I were both on tour and playing the Tin Tan Festival in Spain, and we were actually asked to do a tribute to Jack, which we did. So he was one of the first people that I thought of to invite. And then Helena Espvall, who was the cellist from Espers. They were friends of Jack.

Also, there’s a lot of younger guys on the record now, like Simone Romei from Italy, who was influenced by Jack’s music. I’ve played concerts with just about all of these guys. I was thinking specifically of William Sowell, who goes by the name Prana Crafter. I’ve been a fan of his music and we’ve never worked on a project together. He actually asked me at some point, before the compilation, if there was going to be another Robbie Basho tribute. I thought to ask him right away. He’s one of the guys that I haven’t really met in person. So hopefully the next time I tour in the U.S. I’ll get to meet him and play a show. We’re also thinking about collaborating in the future.

TIDBIT: In curating his tribute album for Rose, Curran asked musicians to contribute what he described as “field recordings,” amassing a collection of performances that ranged from studio tracks to an iPhone demo.

How was the album recorded?

It’s from various sources. I didn’t want to stress anybody out, so I thought I’ll just ask everybody to think of it as field recordings. You don’t necessarily have to go into a big studio to record this. I’m an avid advocate for field recordings. Actually, for Simone’s track, I picked out a track that I had heard by him, and believe it or not he recorded it on his iPhone. The thing was, the source was so good. He was actually very self-conscious, and went into a studio and ended up not capturing the same vibe. So we ended up using the original track.

Community seems to be a thread throughout your career. Any thoughts on why you work this way?

That’s not an easy question to answer, because there’s a lot of things that are related to that. In the ’90s, I ended up moving to Ireland and living with a family in the mountains outside of Dublin. It was kind of communal living. A lot of beautiful things can come of collaborating with people. Musically, I’ve always had this interest in improvisation. With my duo Arborea that I was with for 10 years, Shanti and I started that in a backyard in Maine and we would invite other friends over and have group jams. Really good things inevitably came out of those situations.

There were years before that time where I was always struggling to meet people, you know? When I was in high school, there was hardly any other guitar players or musicians. I went to high school in Ohio, so by reading Guitar Player magazine I would discover Biréli Lagrène from France playing Django Reinhardt style, and read about flamenco players. But I had no way of hearing that music live outside of trying to go and get the albums. As things progressed and I started getting out, touring and meeting everybody … everything started to gel in that way.

Curran is also an excellent electric guitarist, using his Stratocaster, Jazzmaster, and Gibson Les Paul plus effects to conjure atmospheric, ambient soundscapes live and in the studio. Here, he’s onstage with Arborea in Zaragoza, Spain, where the duo opened for Low in 2013. Photo by Marcos Cebrián

How did you get into the style of guitar music you’re playing now?

When I got back from Ireland [in the ’90s], I moved back to Virginia, where I was working at Ramblin’ Conrad’s guitar shop and working for a friend at his deli for a while in the Medical Tower in Norfolk. He was a big fan of Indian music, and played some raga-esque things on the acoustic guitar. But he had a great record collection of a contemporary of Ravi Shankar’s, Nikhil Banerjee. I got really deep into the sitar from his playing. When I first heard it, I just connected so deeply with it. As time went on, I found out about Robbie Basho. When I first heard him, I felt like I understood what he was doing. So it was like a kindred spirit, I guess, if you want to use that term. But I basically had a great interest in songwriting and guitar music and sitar music. So I kind of developed two things separately and combined them.

It doesn’t feel like it’s guitar music in the same way we think of certain techniques or genres of guitar music. It feels really textural and transcendental, in a way.

There’s many things related to why that is, because players are using overtones, they’re using drones, things you find deep in Africa [laughs]. It’s different than classical music that relies on Western harmony. It’s more about melodic ideas.

The other thing is there’s a lot of string buzz. There’s not an emphasis on having this perfect setup where it’s all nice and clean. So you almost get these kind of sitar overtones. And when you’re tuning a guitar down to low C, then the string’s flopping around and the more you drive it with your right hand, you start getting that buzzing. But it’s so funny, you see people criticizing on YouTube, “I think that guitar needs a setup.” Like they don’t know what’s happening. It’s part of the thing.

Guitars

2006 Curran Butterfly

Yamaha F310

Recording King ROS-9-TS

Fender Stratocaster

Fender Jazzmaster

Gibson Les Paul

Amps

Marshall Valvestate VS15R

Effects

Catalinbread Talisman Reverb

TC Electronic Alter Ego V2 Vintage Echo

Acid Fuzz Italian Fuzz

Melody Pedals One Rainy Wish Clean Octave Boost

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EJ16 Phosphor Bronze (.012–.056)

Fender 3150R Pure Nickel Bullets (.009–.042)

DR Pure Blues Light-Heavy (.009–.046)

ProPik Thumbpick

Dunlop Tortex (yellow and orange)

There’s a video of Davey Graham playing “She Moved Through the Fair” in the ’60s in England. He’s been credited with creating DADGAD. He supposedly came up with that when he was living in Morocco or living in North Africa and trying to play with oud players. That performance is so brilliant because it’s that crossover between North African/Middle Eastern music and Irish music. The way that he plays the drones—there’s some rattling that is quintessential with the development of that style of music. Nobody in England was combining it all. It kind of all catalyzed there.

How did you come to know Jack’s music?

I moved to Maine at the very end of 2000, and there was the folk explosion, basically. Which started in my mind by the mid-2000s—you had acoustic players, songwriters like José Gonzalez, Devendra Banhart, Joanna Newsom.

Jack Rose was playing before John Fahey died in 2001, and he started really pursuing compositions in that Robbie Basho/John Fahey style about that time. So about 2004, he was touring around. He did a John Peele session [on BBC radio] when John Peele was still alive ... all this acoustic music was really happening—primitive American style and also freak folk. One of the things he was brilliant at was playing the Weissenborn, the Hawaiian slide guitar. He was playing these long extended raga-type instrumentals on that instrument.

When I first got to know Jack, I would play really hot fingerstyle music, like Peter Finger, who’s a pretty famous German guitarist that plays progressive, hot fingerstyle—all perfectly executed. But Jack right away was like, “I don’t like it. There’s too much going on. There’s no space in the music.” And it was so funny when he said that, because that’s one thing I’ve always connected with in music. Some of my favorite players would create space.

How did you first get into playing guitar?

I would say my first instrument was singing. I was in love with the voice when I was young. My track on the Jack Rose tribute is with slide, and that’s an attempt at a vocalization—to make the guitar sing. I do that quite a lot. I actually use the EBow a lot.

So the guitar was kind of by default because I was already more interested in singing. And my father had a guitar which he couldn’t play, so it ended up under the bed. But I always wanted it [laughs]. And my parents had a great record collection, like John Williams, the classical guitarist, and the O’Jays and Tim Buckley and all this stuff. Aside from the R&B and soul, I would put on a guitar album and just be amazed that someone could make so much sound with just one instrument. So that really started the journey for me with guitar. The first thing I did with my dad’s guitar was just hit notes and see how long it could sustain them.

Here’s a close-up look at one of Jack Rose’s beloved, main instruments: a Weissenborn-style lap-slide guitar custom-made from koa by English luthier Pete Howlett in 1997. Photo by Buck Curran

What guitars do you like?

I design my own acoustic guitars, and I design them to specifically be used for this kind of music. My guitar is built extremely light, with a lot of overtones. It’s got a really tight waist, so it sounds really good in the midrange and great for slide playing as well. It’s made for alternate tunings. So that’s my main acoustic. But I found a super-inexpensive Yamaha that had all these wonderful qualities, and that’s become my road guitar over the last four years—this $140 Yamaha. When they listen to the records people always ask me, “What are you playing?” To give credit to that guitar, when I was shopping for one there were actually four of that exact same model of Yamaha, and that particular one sounded amazing in alternate tunings. There was just something special about it, you know?It’s so funny how all the tiny details in acoustic guitars can add up to make them so individual.Especially the neck. The neck really adds sustain. If you have a good, dense piece of mahogany, it really transfers the sound beautifully.

What are your plans for future projects?

I’m finishing up my next solo record. That’s one of the primary things that I have going on right now. And that’s a combination of instrumentals and songs with vocals. The opening track is called “Blue Raga.” It’s this particular figure and I think it came about after I heard that Davey Graham recording. I don’t ever sit around and listen to other people’s music and focus on what’s going on. It’s just the overall presence of something, you know? And then I kind of think to myself, “Ah, I can do something like that,” and I just start randomly hearing ideas and then I grab the guitar and find them.

My wife here in Italy [Adele H] is an amazing singer and we’re going to be working on her project as well. She was more part of the underground experimental scene in Milan some years ago. We want to do this kind of interesting experimental album with piano and choir vocals. Her music is very inspirational for me. I just love listening to her do her thing.

In this performance of his original piece “Song for Liam,” Curran sums up his affinity for simplicity, space, and long, vocal sustain in guitar music, setting a powerful mood with a limited range of notes.

Seamlessly transferring the spirit of ragas and sitar to the Western, steel-string acoustic tradition, Jack Rose illustrates his distinctly emotive touch while deepening the mood with layers upon layers of repetitive motifs.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.