Photo by Michael Sauvage

Marcus Miller is one of the cornerstones of modern electric bass—a veritable 4-string titan who has played alongside jazz giants (Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Mike Stern, Wayne Shorter, and Stanley Clarke), recorded with rock outfits (Scritti Politti, Doves, Bryan Ferry), and been sampled liberally by hip-hop artists (including Jay-Z and Snoop Dogg). Considering that he’s got signature Fender basses, his own line of DR bass strings, and a massive and dizzyingly diverse discography—as a solo artist, player, and producer—surely he has nothing to prove.

Or does he? Chatting from his home in Los Angeles, the New York City native sounds anything but complacent as he discusses the process behind his new album, Renaissance—his fifth solo effort. “This time I just wanted to make it about the performances,” says Miller, who eschewed the slick R&B production of previous solo albums like 2008’s Marcus and 2001’s M2 for a stripped-down live sound augmented by ace young guns like guitarist Adam Rogers, drummer Louis Cato, and saxophonist Alex Han.

“That’s where the renaissance idea comes in for me,” says Miller, 51. “It’s a return to five or six guys playing in the studio, doing things that, frankly, not everybody can do.” Supported by sultry horns and smart, sassy original compositions like “Detroit” and “Mr. Clean,” Miller lets his funk flag fly high, turning in dangerous grooves and chord changes, as well as stellar solos. Throughout, his cherished 1977 Fender Jazz bass pumps out a fat but intensely detailed tone that perfectly complements his unrivaled thumb technique.

But even after 35 years on the scene—and with his place in music history long since secured—Miller remains creatively restless and determined to push himself even further.

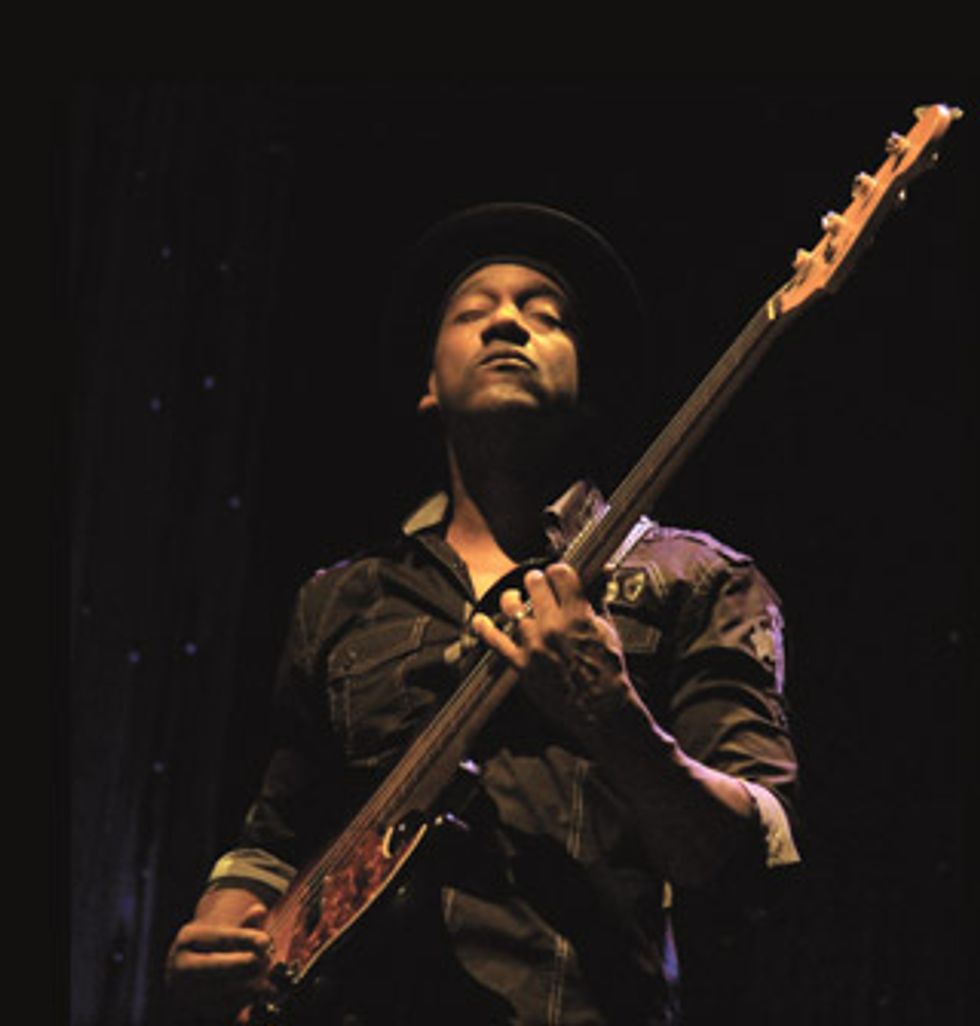

Marcus Miller plucks one of his Jazz basses outfitted with a faux tortoiseshell pickguard. Photo by Michael Sauvage

Is the new album title, Renaissance, intended

to suggest a musical rebirth of sorts?

About five years ago, right after my last

studio album, I said, “Okay, I’m going to

really try to find a new sound.” I intentionally

put myself into musical situations

where I could find some fresh, creative

inspiration. I did a live album with an

orchestra in France [2011’s A Night in

Monte Carlo], I did a live project with

Stanley Clarke and Victor Wooten [2008’s

Thunder], and I did the album Tutu Revisited—an homage to an album I did

with Miles Davis—and many other things.

During the Tutu Revisited tour, I started working with some younger musicians. I hoped that would bring a new energy to some of that Tutu material, which at that time was already 25 years old. I really enjoyed playing with them, and we developed a very interesting sound. I thought it would be nice to write music specifically for this group and do an album that focused on great performances and compositions, not focusing so much on the production, like I had on my last few records.

Electronic music production seemed to

define the last decade, but there’s a huge

return to more organic recording lately.

Yeah, I mean it used to be that if you were

working with samplers, you really had to

know your way around a studio to make

music. But now all you’ve got to do is know

your way to the Apple store, and you can

figure out how to do that stuff. For me,

what makes what we as musicians do special

is our ability to perform it right there in

real time. So I figured I’d try to display that

instead. I mean, the sampling thing is

cool—whenever new creative approaches

present themselves, it’s up to us to see

what we can do with it, and I love what

we were doing with the samplers—but at

this point, it feels like what’s really fresh

is just to strip it down.

Miller on His Go-To Jazz Basses

“Man, there are advantages to playing the same instrument for 35 years!” laughs Marcus Miller, whose workhorse 1977 Fender Jazz Bass—outfitted with a Bartolini preamp and a Badass bridge—is the very same instrument he played on Miles Davis’ Man with the Horn album in 1981 and on late-’70s sessions with artists like Luther Vandross and Joan Armatrading. “When you’ve played an instrument that long, you really know all the sounds it’s got to offer.” Miller’s Fender signature model Jazz bass pays tribute to the original and features a natural finish, a 2-band active EQ, a Badass II bridge, and, of course, the distinctive chrome pickup cover.

“I bring one of my [signature Fender] 5-strings on the road with me,” Miller adds, “but a lot of times I’ll just tune my 4-string’s E down rather than take the time to switch basses—because I got so used to doing that from my session days. A lot of those old Luther Vandross R&B records were drop C, and even with Miles I was often down to an A on the bottom. I had octaves going, A to A, on the bottom, and man, it was pretty tubby sounding. But back in the ’70s, before they had extended-range basses, that’s how you did it—and you knew your fingerings in D and C just as well as you knew them in E.” —James Rotondi

“Redemption,” “Mr. Clean,” and

other songs on this album have some

great solos. How is approaching a

bass solo different than approaching

a guitar solo—does it come down to

harmonic support?

For a bass player, there’s an inherent

requirement to maintain a sense of

rhythm and to really present the harmony

very clearly—because usually

there’s no one else holding that down for

you. I have a couple of different ways to

approach it: A lot of my solos are basically

glorified, involved bass lines. So,

in a sense, it’s as if there were someone

still playing the bass—it just happens to

be me while I’m soloing. I like to play

“question-and-answer,” where I’ll play

the question up high, and the answer

down low, so there’s always a kind of

rhythmic and harmonic motion going

on. So that’s one challenge, that there’s

no bass player behind you.

But also, a lot of the time, there’s no harmony behind you, either. If the piano and guitar player are playing too busy, obviously it can cover up what you’re doing. But if you ask them to be more sparse, then you’re going to have to be more clear about the harmony. Unfortunately, a lot of bass players aren’t that familiar with harmony, and that’s where they can get into trouble. You don’t have those kinds of concerns with guitar. If you play an Ab major triad on guitar over a D bass note, it’s clear what you’re doing. If you do it on bass, it’s just an Ab triad, unless you’ve figured out how to make people hear that D as well.

Personally, I don’t really enjoy hearing a bass playing melodically by itself with no underpinning. To me, it sounds like a lot of the information is going on in the bass player’s head. Sure, he’s hearing the harmony and the rhythm, but no one’s actually playing it, so what is the listener really getting? Another solution, of course, is to just have somebody play bass under you—which I’ve done from time to time—and there you’re a little more free to leave space and to phrase in a more vocal-like manner.

Miller’s primary bass for the last 35 years is a 1977 Fender Jazz model outfitted with a Badass bridge and a Bartolini preamp. Photo by Michael Sauvage

Has your plucking-hand technique

changed much over the years?

I attack the string with my thumb pretty

much the same way I always have—just

beyond the end of the neck—because

that’s a really sweet spot on my particular

instrument. Some guys do it more on the

neck, which creates more false harmonics.

I’ve always hit just in front of the end

of the fretboard, because I need a sound

that’s strong on the fundamentals. But it’s

changed with my plucking fingers, and

it’s pretty fluid—even when I’m doing the

thumb-style playing. When slapping, I used

to only pluck with my index finger, but

I started incorporating my middle finger,

as well. And when I’m using the thumb

more like a pick, moving up and down the

strings, I have to move my thumb away

from that sweet spot to make sure I can get

even strokes going up and down.

When I was doing sessions all the time, I’d pluck in the standard spot for a Jazz bass, which is just between the two pickups—where that meaty sound is. When I started making solo records, though, I began to address the fact that I never liked the transition from fingerstyle to slap and plucking style. So I started doing my fingerstyle strokes really close to the neck, using a really heavy attack, so that it almost sounded like a full pluck even though it was a finger stroke. That way, when I switched over to a thumb and a pluck, the sound was more consistent. On my own albums, you’ll almost always hear me using that style.

Over the last few years, I’ve started to move my right hand back and forth a lot more, all over the bass, and it’s helped me realize that I don’t need to fool around with my tone [settings] as much if I just choose a different placement of my fingers—and that allows me to play in very different ways.

What sorts of ways?

You can play way back by the bridge, and

another great spot is just about an inch and

a half to the left of the back pickup. It still

really sings, but you also get a little more of

the meat that you don’t when you’re all the

way to the back pickup.

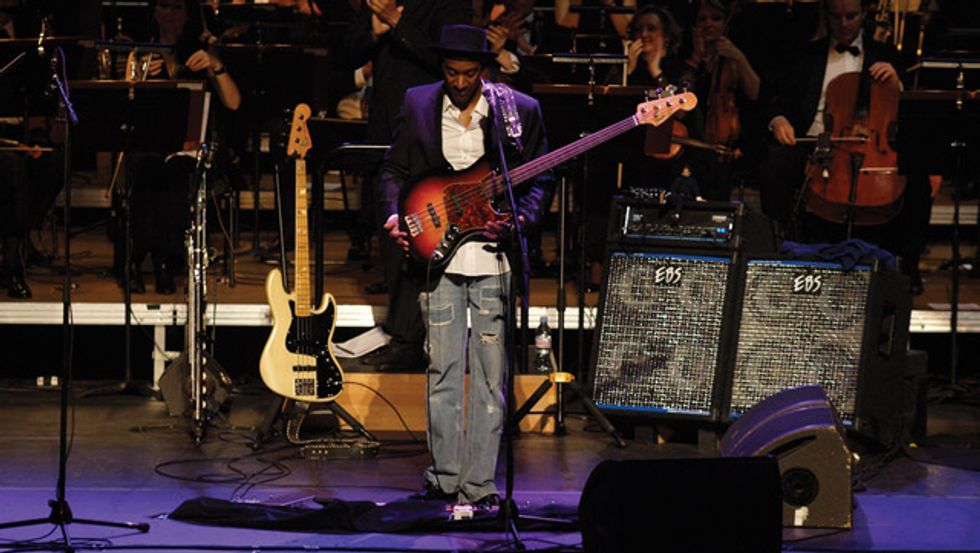

Miller onstage with a sunburst Fender J and an EBS

TD660 head driving twin EBS 4x10s. Note the Bionic

Man ... er action figure sitting atop the EBS rack.

Photo by Andrea Scognamillo

What do you practice these days—is it

still mostly scales and arpeggios?

I start by just warming

up, which is really important.

A lot of younger players don’t realize

that. I’ll just play scales really slowly, usually

when I’m talking with somebody and going

over the set before soundcheck—just to get

everything moving. And then I’ll find scales

that involve all the fingers—for instance,

whole-tone scales in different permutations—just to get all my fingers moving.

For example, I might play the notes Bb,

Db, A, and G using a 4–2–3–1 finger pattern

on the E and A strings, and then move

that pattern—and variations on it—up

and down the neck. I’ll use both scales and

arpeggios for that.

Then I’ll move into some bebop-based stuff, because I’m always trying to keep that connection between my imagination and my technique. I’ll improvise and try to play exactly what I’m hearing in my head. And if I get stuck, and I can’t play what I’m hearing, I’ll make a little exercise out of it and work on that until it’s happening. That type of practicing takes me all over the place, and that’s necessary, because I do a lot of improvisation, and I really need to be sure I can get to where I need when I want.

Sometimes, I’m running standard jazz-tune changes. Other times, I may be superimposing harmony over a single chord, like I was talking about earlier, to really get a sense of working the melody, harmony, and rhythm all at the same time. I’ll usually end up playing with different rhythms—keeping the beat, but flipping it around and turning it upside down, while making sure it’s steady and feels good. Because, in the end, if you don’t bring together all the stuff that I’m talking about in a rhythm that feels good, it’s kind of meaningless.

Marcus Miller's Gear

Basses

Various 1977 Fender Jazz basses, Fender

Marcus Miller Jazz signature 4-strings,

Fender Marcus Miller Jazz V 5-strings

Amps

SWR Marcus Miller bass preamp and

SWR Power 750 power amps driving SWR

Marcus Miller Golight 800-watt 4x10 cabs

(live), EBS Fafner II head driving EBS

NeoLine Pro 4x10 cabs (live)

Effects

MXR Blow Torch, MXR Bass Octave

Deluxe, MXR Bass Compressor, MXR

Phase 90 (“for whenever I want to

play “Money, Money, Money” by the

O-Jays”), MXR Micro Flanger, Dunlop

Cry Baby 105Q wah, Fulltone OCD

(used on the ballistic third chorus

to the new album’s “Detroit”), a

Rodenberg GAS-808, Electro-Harmonix POG, Ernie Ball volume

pedal, Sanford & Sonny Bluebeard

Fuzz, dbx 166 compressor (studio)

Strings and Picks

DR Strings Fat Beams Marcus

Miller 4- (.045–.105) and 5-string

(.045–.125) sets, DR Hi-Beams

In the ’80s and ’90s, you

played and recorded with

everyone from Peabo Bryson to

Luther Vandross, Mariah Carey,

David Sanborn, and Paul Simon.

You even played on Donald

Fagen’s 1982 masterpiece, The Nightfly.

What were those early days as a session

cat like?

As a studio musician in New York, there

are two types of players. There’s the musician—more of a chameleon—who’s good

at finding the sound that’s necessary for

a particular record, and then there’s the

guy who you don’t call unless you want

his unique sound. I was somewhere in the

middle. I’d get to the session and see what

was required, and if it seemed like they

were looking for the kind of sound everybody

knew me for, I’d break that out. But

other times, it was clear that my regular

style wasn’t going to be appropriate.

Donald Fagen, for instance, wanted a straight, clear fingerstyle Jazz bass sound. That was my first time working with Donald and his producer Gary Katz. All the studio musicians in New York were warning me about Fagen. “Man, he’s going to have you playing that thing over and over until you get it right!” He was famous for that. So I came in ready to spend lots of time there, and I did four or five songs, two takes each, and he said, “That’s great!” and sent me on my way. I was like, “Hey, that didn’t hurt at all!” Now, I did hit him with a little thumb [playing]—but he took it off. I hit “I.G.Y.” like a gospel shuffle—like a Luther Vandross “Bad Boy/Having a Party” funk style—and he was, like, “No! Way, way too exciting—thank you very much!”

YouTube It

Need video proof of how badass Marcus Miller is? Click to the world’s TV and find out.

Snapping and popping rule the day

in this clip from Miller’s 2008 stint at

the annual Lugano Festival Jazz in

Switzerland.

>

Miller displays his impeccable fingerstyle

work in this 1982 clip with Miles

Davis and guitarist Mike Stern at the

Hammersmith Odeon in London.

On this rendition of the Jaco

Pastorius/Weather Report classic

“Teen Town,” Miller gets in a major

hammer-on workout before taking the

funk factor to the nth degree.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)