Just ask acoustic guitar players, builders, and fans: They'll tell you we're in a golden era for the instrument. Not only are such venerable companies as Martin and Gibson producing some of the best new guitars in their long histories, but they're also delivering the most accurate reissues of their storied prewar classics. Independent luthiers around the world are crafting acoustic guitars of stunning quality, in every conceivable style from recreations of 19th-century parlor guitars to bold modern flattops that upend every aspect of traditional design.

At the same time, the acoustic guitar has never seen so many inventive practitioners. Virtuosos as far-flung—musically and geographically—as Richard Thompson, Tommy Emmanuel, and Pierre Bensusan remain vital after having collectively logged more than 130 years as music professionals. Thousands of younger guitarists have discovered these players' work, while simultaneously deriving inspiration from the American Primitive school. The latter includes John Fahey and Robbie Basho—steel-string pioneers who recorded in the 1960s and '70s on Takoma, the label the late Fahey started in 1959.

And these younger pickers aren't content to copy, but instead strive to forge personal, idiosyncratic styles from their many influences. To illustrate the diversity and creativity of this new generation of acoustic guitarists, we spoke to five emerging players who are making waves with their performances and recordings. Daniel Bachman, Tashi Dorji, Chuck Johnson, Adam Miller, and Cian Nugent cover a wide range of stylistic territory, and their music offers a glimpse into the state of contemporary acoustic guitar.

Bachman, Johnson, and Nugent are clearly indebted to Fahey and other Takoma fingerpickers, but because they bring many other influences to the table, they hardly sound derivative. Inspired by guitarists like Joe Pass and Charlie Hunter, Miller has developed an uncanny polyphonic approach to jazz. Coming from an entirely different direction, Dorji takes his cue from Derek Bailey and other iconoclastic musicians, and freely improvises stunning—and challenging—soundscapes.

Though all five guitarists sometimes play in ensembles, each really shines in the context of solo performance. For the most part, they avoid overdubs and electronic effects in the studio and onstage. And they all make the most out of a meager selection of gear. For example, Dorji favors a Hohner HW605, an example of which this author happened to find at a local thrift store for a mere $50. Once again, this proves the adage: It's not about what you play, but how you play.

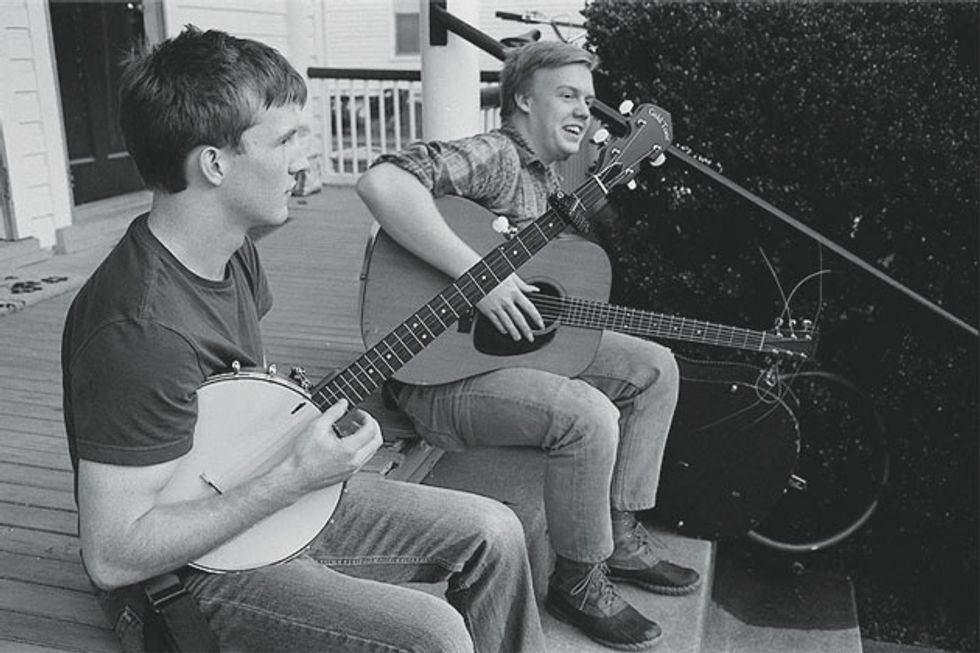

Daniel Bachman

At 24, Daniel Bachman is a young fingerstylist with an old musical soul. The Virginia-based guitarist is steeped in the music of the American Primitive players, and it's clear he's carefully studied both their stylistic antecedents and the traditions of his native South. Bachman synthesizes everything into a highly personal, mature style that belies his youthfulness.

Bachman's impressive command of the steel-string, plus occasional forays into the worlds of banjo and sitar, can be heard on the flurry of singles, EPs, and albums he's recorded in the last half-decade. His two recent full-length efforts, Orange County Serenade and Daniel Bachman, are testaments to the breadth of his musical knowledge and curiosity.

You grew up in a very musical household. What was that like?

Both of my grandfathers were professional musicians at one point. So was my dad, who started off playing in a Fred Neil-Tim Hardin vibe. I grew up with guitars all around the house and tunes constantly playing. It was definitely hard to get away from music at home. My dad typically has four guitars at any given time. He once played a 1969 D-18, and that's now my main instrument. Come to think of it, most of the guitars I've ever owned have once belonged to my dad.

What are some of the less obvious influences on your playing?

I'm not religious, but I'm really into the heavy holiness gospel stuff by a lot of unknown musicians no one really cares about—a lot of the older camp-meeting stuff. The vibe of that music just hits me really hard. I listen to pretty much everything these days, including a lot of electronic music. Lately I've been checking out Laurie Spiegel, who was also a great guitar, lute, and banjo player. That electronic music actually works really well when applied to an open tuning, where you're working with a very specific set of notes.

Which open tunings do you prefer?

Open C is really versatile in that you can tune the first string down a half-step [to Eb from E] for a C minor tuning or by another half-step [to D] for a sus tuning ... pretty drastically different sounds. With the first string at Eb it sounds very harsh and minor, but when it's at E natural, it's so bright—like a lovely, sunny day.

I've finally gotten into open G, which is a tuning that freaks out a lot of people because of the low D. I just kind of ignore the 6th string—I don't even touch it. To me, open G is kind of a golden tuning, the most classic one there is.

Daniel Bachman's Gear

Guitars

1969 Martin D-18

1980s Guild D-50

No-name custom Weissenborn-style guitar

Strings and Picks

D'Addario EJ17 Phosphor Bronze (.013–.056)

Dunlop brass thumbpicks

Stevens bar slides

Tell us about your compositional process.

I don't have a full-time day job, so I treat writing as my 9-to-5 thing. This gives me the luxury of putting together songs I'm really proud of. In the past, I've been frustrated by tight deadlines and have admittedly put out things I'm now embarrassed by.

I'll sit with a lick until it develops into a great A section. Then, I'll think about how long I want the song to be, whether three minutes or 10, and

come up with the rest of the piece using a similar process. Working with open tunings, it's easy to have lots of different chords at my disposal and to figure out how to put parts together in an organic way.

How does improvisation figure into your music?

In a sense, my writing process is all about improvising, pulling things left and right out of nowhere. Once I've finalized a tune, I stick to it pretty strictly, but maybe with some deviations in terms of chord voicings, dynamics, and tempo that change from night to night when I play it live. Basically, I'm just trying to write songs and play them as best I can.

How has your playing evolved over your last several years as a recording artist?

The other day I was talking to this dude about my playing when I realized that it has shifted a lot. I've always wanted to play slower, with more guts and emotion, but for years I could only blast through tunes. It was almost too hard to play slow, and I'm just now opening up to it. At the same time, I'm constantly listening to as much stuff as I can and trying to cop new ideas. I'm always trying to get just a little better.

Photo by Jason Scott Furr.

Tashi Dorji

Tashi Dorji is the most strikingly original musician of this roundup, in part due to geographical circumstances. The 36-year-old guitarist grew up in Bhutan, the small mountainous country whose neighbors include India and China. A lack of internet and television limited Dorji's access to the information guitarists in other parts of the world took for granted, and he was forced to rely on his ear and his imagination to learn how to play on a nylon-string guitar whose setup was suboptimal.

In 2000, Dorji moved to Asheville, North Carolina, to attend Warren Wilson College. But the sheer volume of new music he encountered distracted him from school. He lived with roommates who introduced him to punk rock, and he also got entrenched in free jazz, noise, and the avant-garde in general, devouring the catalog of every artist his friends mentioned.

After a few years, Dorji dropped out of school to focus on music. He has since developed a style of free improvisation—all of his pieces are spontaneously composed—in which he gives equal consideration to metallic-sounding gestures and lush harmonies, as heard on recent releases like his self-titled vinyl debut album or the blue nest of larks that die EP (available on his Bandcamp page).

What was it like to learn the guitar in Bhutan?

It was very different. I had really limited access to sounds—only shortwave radio and a national station that played hits three to five years after they came out, which I listened to on this mini boombox. I was also exposed to traditional music, a lot of monastic music from the northern part of the country, with dancing and drums.

In high school I started swapping bootleg cassettes from India, and I got exposed to Bollywood and a lot of music from the U.S., mainly classic rock. When I was in 9th grade, one of my friends had a cheap nylon-string guitar, and after I learned a chord or two on it, I convinced my mom to get me a guitar of my own. My friend then taught me a few easy Neil Young songs that he learned from a tab book he'd managed to get his hands on.

I didn't have a television or the internet, and, not being able to see what guitarists were doing, I had to figure out things on my own. Since I had a good ear, I was able to listen to Nirvana's Unplugged and teach myself the chords. Those were essentially my lessons—learning Nirvana songs from Indian bootleg cassettes.

Describe the impact Derek Bailey has had on your music.

I first heard Derek Bailey around 2007, but didn't delve deeply into his music until several years later. I'd moved temporarily to Maine and found his CD Standards at a used record store for five dollars. It completely moved me and affected me deeply in a lot of ways. It was a huge epiphany. I've always been wary of school, of the institutionalization of the mind, and hearing something completely removed from tradition or dogmatized playing really freed me. It gave me permission to approach the guitar in a very nontraditional way.

Tashi Dorji's Gear

Guitars

Hohner HW605 concert-sized steel-string

Ibanez 2839 nylon-string

Strings and Picks

D'Addario EJ17 Phosphor Bronze (.013–.056)

Martin M120 Silverplated Classical (.028–.043)

You use extended techniques judiciously in your playing.

I'm obsessed with finding percussive sounds on the guitar, and extended techniques drive me into those realms. I insert bobby pins, chopsticks, or whatever else I can find between the strings, to create really percussive, metallic textures. Sometimes I'll clip a safety pin around a string so that it creates a complex buzzing sound. By using these techniques, along with more conventional ones like harmonics, I can create tension, color, and dynamics.

Do alternative tunings determine your improvisations, or is it the other way around?

I think it works both ways. Some guitarists reserve specific tunings for certain styles of performances, but I really don't. I like to play around with different tunings at every live show, and often come up with them on the spot. Sometimes I just try to come up with a tuning that sounds weird, and that definitely dictates how I play. But generally, I'm really open to new tunings. I don't have any specific agenda.

What do you think about, structurally speaking, in your improvisations?

Sometimes I try to come up with a head, so to speak, and play variations on it. Other times, I decide if the piece will be a long or a short one, and just see where the music takes me. I've found my state of mind also determines the content. When I'm caffeinated, I find myself playing faster, with jittery textures. But the thing is, my structure is essentially no structure. It's kind of anarchistic in a way.

You don't seem to be much of a gearhead.

I only play two acoustic guitars that I bought used—a small steel-string Hohner and an old Ibanez classical guitar. I don't really care too much about what I play. I guess I'm not such a good subject for a guitar magazine! [Laughs.]

Photo by Omid Zoufonoun.

Chuck Johnson

As an acoustic guitarist, Chuck Johnson might fall under the American Primitive umbrella, but his musical life has been much more expansive than that label suggests. Throughout the 1990s in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Johnson played electric and acoustic guitar in various bands whose music resisted categorization. He also dabbled in free improvisation under the name Ivanovich.

At the beginning of the next decade, Johnson set aside his 6-strings to focus on electronic music, not just composing but also building his own circuitry and instruments. This pursuit took him in 2007 to the West Coast, where he earned an MFA at Mills College while studying under the maverick composer and accordionist Pauline Oliveros.

In recent years, Johnson, 46, has rekindled his relationship with the guitar. He's developed an idiosyncratic fingerstyle approach equally indebted to folk guitarist Elizabeth Cotten and minimalist composer Terry Riley—an approach he's explored on solo outings A Struggle Not a Thought (2011), Crows in the Basilica (2013), and the forthcoming Blood Moon Boulder. Johnson's guitar can also be heard on the HBO documentary Private Violence and the PBS show A Chef's Life.

—Chuck Johnson

How did you discover fingerstyle guitar?

In the mid 1990s, I came to play fingerstyle in an atypical way. My mother had given me a banjo and I was trying to learn to play it Scruggs style, with three fingers and in open tunings. But then I discovered Elizabeth Cotten and transferred her approach to the guitar. I started picking up guitars, retuning them, and using some of the same picking patterns I'd learned on the banjo.

Who are some of your benchmarks in that arena?

I'm definitely influenced by Elizabeth Cotten and other Piedmont blues players like Etta Baker, Reverend Gary Davis, and Mississippi John Hurt—all of whom have a sort of laid-back swing that comes from a ragtime influence.

Within the American Primitive canon, for depth of repertoire, and inventiveness with regard to syncopation and pathos, there's John Fahey. For cosmic individuality and weirdness, there's Robbie Basho, who didn't sound like anything that came before him. Then there's Peter Lang, who brings such a lyrical quality to the melody. He's maybe not as known as the bigger names, but I've related more to him over the years than to someone like Leo Kottke, whom I admire but whose work I'm not as excited about.

Chuck Johnson's Gear

Guitars

1966 Guild F212 12-string

Larrivée L-01

Lazy River Weissenborn-style baritone lap slide

1931 Supertone Bradley Kincaid parlor (restored by luthier Trevor Healy of Healy Guitars)

Tacoma PM28 parlor

Strings and Picks

D'Addario EJ16 Phosphor Bronze (.012–.053)

Martin M120 Silverplated Classical (.028–.043)

How have you reconciled the worlds of electronic music and fingerstyle acoustic guitar?

With electronic music, I'm generally more interested in vertical qualities of sound—timbre, overtones, and feedback. It wasn't until after I finished my studies at Mills that I realized that wasn't so different from what I like about acoustic guitar: open tunings bring out overtones, making for a rich and resonant sound. The trick with my solo acoustic work has been instead of doing something abstract, as with my electronic music, to strike a balance between a vertical approach and an interesting melody or linear, narrative form.

Which tunings do you prefer?

At this point I have a small handful that I use, as I don't like spending a lot of time tuning in shows. The ones I prefer are well-known in folk music: open D, D minor, G, and occasionally DADGAD. I also use open C or C minor, sometimes tuning the first string down to D, for a more ambiguous quality.

Do the tunings inform your compositions or the other way around?

Alternate tunings are definitely part of my compositional process. I think of each tuning as a different system to work within. I think it's like putting together a puzzle, really just sitting down with a tuning and finding a melodic line that I can use to connect chords. From there, I add other ideas and shift around bits and pieces, adding what makes sense and taking away what doesn't.

How does the acoustic guitar factor into your work as a film composer?

Being a fingerstyle guitarist has definitely worked out in my favor for film work, as it seems to be a popular choice for soundtracks these days. Generally people who ask me to do this are already familiar with my work as a solo guitarist. It's relatively easy for me to write in such a compact form, little compositions that range in duration from 30 seconds to a minute at the most. The open tunings tend to give me immediate access to fresh ideas.

Photo by Megan Woods.

Cian Nugent

After he learned to play Doc Watson's version of “Deep River Blues," Dublin-based guitarist Cian Nugent began to explore the acoustic worlds of John Fahey and Bert Jansch, which he used as a point of departure for his own idiosyncratic approach to the guitar and songwriting. Like Daniel Bachman, Nugent, who is 25, now plays with maturity beyond his years.

Nugent has been playing professionally since he was a teenager. In 2007, he released a self-titled debut, largely in the Fahey tradition, and has since toured Europe and America with fellow guitar explorers Glenn Jones and Steve Gunn, among others. In the process, Nugent has broadened his approach, assimilating psychedelic sounds and more abstract improvisations into his solo and ensemble music, heard to excellent effect on his most recent album, Hire Purchase.

How did you develop your highly personal style—did it evolve naturally, or did it involve a concentrated effort?

Well, I always preferred the sound of playing quietly rather than hammering hard on the strings. I've also always been a fan of recordings by players that draw you into them, rather than loudly pronouncing their purpose. I've always aimed to bring people in to what I'm playing rather than playing hard in order to be heard. That said, I've been known to kick up a shit-storm with a guitar. What's the point in having ideas about how to do something if you only adhere to them?

Who are some of your benchmarks, both in terms of acoustic guitarists and music in general?

Two of the guitar players that have had the biggest impact on me are John Fahey, for his sense of pacing—he kept it slow without it dragging and was rich with pain—and Richard Thompson, for his refined sense of touch. Thompson showed me that you can play the blues without having to sound American.

Beyond guitar players, the way John Lennon and Bob Dylan shape harmony and melody is kinda written in my blood. I love the Azerbaijani saz player Edalat Nasibov. My friend Chris Hladowski calls him the Jimi Hendrix of the saz, and I know what he means: Edalat really gets your blood flowing and his sense of improvisation is so vital. The joyous dialogue between John Coltrane and Elvin Jones is always something I hold as an archetype of musical achievement, too.

Talk about a musical epiphany.

A big thing was learning about open tunings. I can't recall the first song I learned to play in an open tuning, but I remember the sense of freedom it allowed me, being able to go up the neck for melody and not being bound to playing chords and melodies that fit around them. In a way I feel like I've been working backwards, because recently I've been really enjoying playing in standard tuning and exploring within its confines. Sometimes open tunings can be like going to an all-you-can-eat buffet—there's a whole lot of stuff there, but you don't know where to start.

Cian Nugent's Gear

Guitars

1979 Guild G37 with 1970s DeArmond pickup

Amps

Sound City Concord combo

Strings and Picks

D'Addario EJ17 Phosphor Bronze (.013–.056)

Golden Gate thumbpicks

Acrylics from nail salon (on index and middle fingers)

To what degree does improvisation feature into your music?

I used to be totally unable to improvise, but slowly got more and more into it. I made an album of entirely improvised stuff with Steve Gunn and John Truscinski, and I learned a lot from that. I think we all shared an aim of what we wanted the music to do, and where we wanted to go with it. I think that's important when you're improvising—that you're playing with people who are on the same page.

What I love about improvising is that you can achieve shared heights with other players that can totally surprise you and that wouldn't have happened if you had everything scripted. I like to have space for improvisation in music that can go on for as short or as long as feels necessary. That way you can respond to the feel of the day, room, people, etc. I think that's the magic of improvisation: Sometimes it really works and sometimes it doesn't.

How would you describe your overall philosophy when it comes to playing the acoustic guitar?

I think it's important to play guitar from your stomach—that's where it sits and that's where you should feel it. Guitar is the most common instrument in our society and that's what I love about it. There's always a guitar in someone's house—it's a shared language, like folk music. But that familiarity can grow boring, and we can get sick of the tropes of guitar. So I try to be in a place musically that is familiar, but hopefully not too much so. I try to play the song you remember, but can't place.

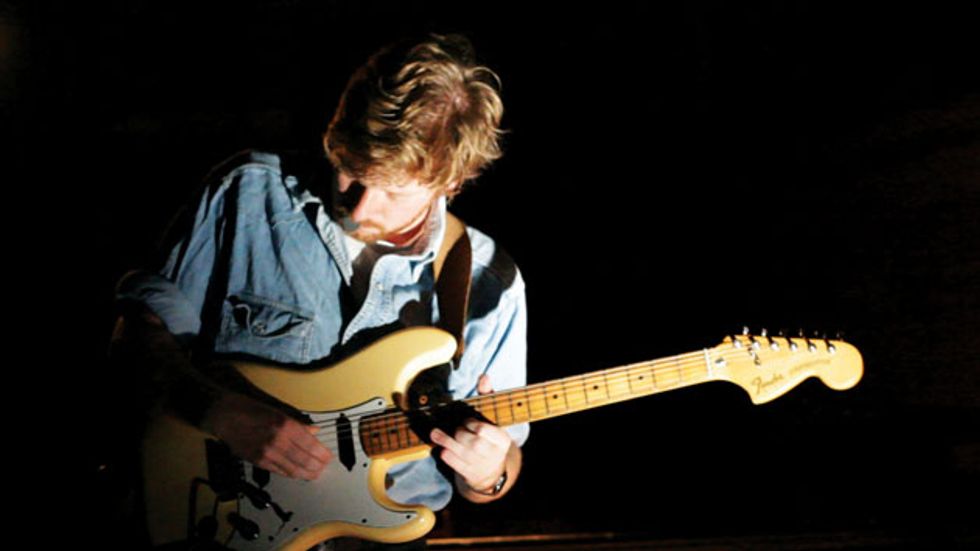

Adam Miller

With practice, a competent guitarist can learn to play a highly polyphonic piece of music by breaking it down into its individual components and slowly putting them together. But it takes an impossibly gifted player to improvise independent melodies, harmonies, and bass lines—all at the same time—while maintaining an impeccable groove. Australia's Adam Miller is one such rare phenomenon.

Miller, 34, first discovered the acoustic guitar through Tommy Emmanuel, whose virtuosic stylings he copped as a preteen. By 15, Miller was opening for Emmanuel in concert. He has since shared the stage with Les Paul, Martin Taylor, and Charlie Hunter, among others, while releasing a series of solo albums beginning with 2001's After One Day.

No slouch on the electric guitar, Miller stretches out in an ensemble with some of Australia's leading jazz musicians on his most recent album, Shifting Units. On the same release, Miller plays each of the compositions unaccompanied on acoustic guitar—evidence not just of the brilliance of his technique, but of the durability of his compositions.

Tell us about your formative musical experiences.

I started playing organ when I was about 4 years old and picked up a guitar at around age 9. I remember really loving Billy Joel's Storm Front album, but couldn't sing anything like Billy with my 9-year-old voice. My mum bought me Tommy Emmanuel's album Dare to be Different around the same time—1990, when Tommy was starting to become a household name in Australia. I thought I could sound like that because he wasn't singing, just playing the guitar. Of course I had no idea how difficult it was! But that was probably good, as I just tried to play like that without thinking anything of it.

How did you develop your highly polyphonic approach to the guitar?

It really came as a consequence of culture in some ways. It was trying to play the type of music I really enjoyed, but often having to perform solo. I started playing proper alternating-bass fingerstyle in my late teens, but aside from playing guitar shows, no one really got it. I was also playing a lot of electric guitar in funk, pop, and jazz band settings, and pulling good audiences. I always wanted my solo guitar music to groove more and have elements of improvisation, but didn't realize it was possible until I heard CharlieHunter. It really opened my mind to what you could accomplish as one person.

I started playing an 8-string guitar like Hunter, but really found my voice when I applied those ideas back to the 6-string. The technique I've developed really is very dynamic. I'm able to come up with arrangements very quickly and improvise quite freely—in both the bass line and lead line. It allows me to perform and compose songs in a greater variety of styles than I find with the traditional alternating bass patterns. It also allows me to imply a strong groove without the need to add tapping and percussion.

Adam Miller's Gear

Guitars

Jeff Traugott 00 fan fret

Ryan Thorell custom archtop (on order)

Pickups and Sound Reinforcement

Seymour Duncan Mag Mic

DPA 4061 omnidirectional miniature mic

D-Tar Solstice preamp

Two-Rock Coral amp

Two-Rock EXO-15 amp

Effects

Strymon TimeLine delay

Disaster Area DMC-3 MIDI foot controller

Strings and Picks

D'Addario EXP16 coated phosphor bronze (.012–.053)

Analysis Plus cables

Which non-guitarists have informed your approach?

With bass playing such a huge role in my solo music, it's probably pretty obvious that I love listening to bass players and trying to incorporate what they do. I learned all the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Rage Against the Machine bass lines as a teenager. Other bass players that have had a huge influence on me have been Andy Hess, Pino Palladino, and the Australians Steve Hunter, Mitch Cairns, and Peter Gray, all three of whom played on my new album, Shifting Units.

I also draw inspiration from the feel of drummers like Matt Chamberlain and Steve Jordan. Ben Folds is a big influence, too. I love the way the piano works in the trio environment and really use that as a muse for how you can play polyphonic parts on the guitar within the context of a band.

How do you sum up your overall philosophy when it comes to playing and composing?

I try to compose as simply as possible. It's easy when you're into jazz to get lost in changes and complex melodies. I do a lot of shows with a band and we don't often have the luxury of rehearsal. By having simple tunes, my band can imply their own voice easily. Same goes for when I perform solo, in that I'm able to take the audience to a different place each night. I don't write for solo guitar. Instead, I end up arranging my compositions back to solo guitar. In fact, the whole idea of Shifting Units was to demonstrate just that.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.