Since bursting on the scene with Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen in the late ’60s, Bill Kirchen has been at the forefront of twangcore and hillbilly rock. As one of the first to bring the spanky sounds of Tele pioneers Roy Nichols and Don Rich to the Woodstock generation, Kirchen has rightfully earned his “Titan of the Telecaster” moniker by playing a soulful mix of rockabilly, Western swing, blues, and honky-tonk.

Kirchen’s musical journey began in the early ’60s in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he was exposed to the burgeoning East Coast folk scene. After forming a band with several University of Michigan buddies, including George Frayne (better known as Commander Cody), Kirchen convinced his cohorts to migrate to San Francisco in 1969. The timing was right for the Lost Planet Airmen, who quickly became part of the musical mayhem that defined the era, joining the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers, and other top bands on the national concert circuit. The Airmen’s first two albums—Lost in the Ozone and Hot Licks, Cold Steel, and Trucker’s Favorites—yielded several classics of the day, including “Seeds and Stems Again Blues,” “Mama Hated Diesels,” and the band’s Top Ten hit, “Hot Rod Lincoln.”

Four decades later, Kirchen shows no signs of slowing down. “Actually, I think I’m getting better,” he says, “though I don’t take it as a badge of honor. I attribute this to one thing: I’m an extremely slow learner. I woke up at age 59 and went, ‘Oh yeah, I get it—that’s how you’re supposed to sound.’”

Since playing with Commander Cody and crew, Kirchen has released seven solo albums and toured and recorded with such notables as Danny Gatton, Emmylou Harris, Link Wray, and Gene Vincent. For his latest album, Word to the Wise, Kirchen invited a handful of musical compadres and former bandmates— including Commander Cody, Dan Hicks, Norton Buffalo, Nick Lowe, Paul Carrack, Blackie Farrell, Maria Muldaur, and Elvis Costello—to join him in the studio for a series of duets. The result is a deeply satisfying mix of originals and covers that runs the gamut from twangy honky-tonk to gritty pub rock.

We recently asked Kirchen to tell us about recording Word to the Wise and what gear he used to create his trademark Tele sounds. With a seasoned storyteller’s dry sense of humor, he delivered the goods.

Where did you get the idea for recording an album of duets?

It was really the record company’s idea. I was reluctant at first, because I didn’t want to be the guy who drags other people into his project simply to sell records. It got okay in my mind when I figured out I’d only ask people I’d worked with professionally to be on the album. Once we’d settled on that criterion, it became fun and I enjoyed asking everyone to participate.

How did you choose your collaborators?

Some of them were musicians who inspired me before I ever got up and running in this business. Both Dan Hicks and Maria Muldaur fall into that category. When I had my first band, the Seventh Seal, back in Ann Arbor, I bought a Charlatans record that featured Dan, and I drew a lot of inspiration from it. And many times I’d hitchhike to Boston to hear the Kweskin Jug Band with Maria at the Club 47. I heard them at the Newport Folk Festival in ’64 and ’65, too. So Maria and Dan were heroes of mine from the ’60s. I’ve played with Nick Lowe and Elvis Costello over the years, so they were a natural fit. Blackie Farrell and I have been writing music since the Commander Cody days. The one stretch is that I’ve never performed professionally with Paul Carrack, but I have sat in on his stage and he has joined me on my stage, so I figured that’s okay. The fact that money never changed hands is immaterial.

Where did you record Word to the Wise?

We cut the rhythm section in the UK and then went around the world to harvest the vocals with a laptop, recording people where they live. For instance, we recorded Chris O’Connell in Virginia and I got Cody in Albany, New York. Sometimes we carried the tracks on a hard drive into the studio to record vocals, like when we went across London to record Nick and Paul in Nick’s studio. We had to record Elvis Costello by mail, because we had a brief window of opportunity when he could do it, so I didn’t get a chance to go there and watch him track his vocals. We definitely had to time shift to get this record out. That’s the great thing about digital recording these days—it’s much easier to accommodate everyone’s schedules.

Did you cut the rhythm tracks together as a band?

Yeah, the rhythm tracks are all live. I overdubbed all the solos and most of the fills and lead parts at a later time. I have an Apple Logic rig at home, and I did vocal harmony and guitar overdubs after the fact at my house.

Yet it sounds like you didn’t fall into the trap that so many of us do, which is, “Hey—I can tear this song apart and redo everything, note by note!”

It’s a slippery slope, man. I have to admit I’d sometimes find myself sitting there slack-jawed in front of the computer, hitting the space bar to redo a few seconds of guitar after having literally recorded 50 tracks of that part. And it’s not getting any better, you know? Every take is slightly worse than the one before—it’s a trap. I’m not trying to say overdubbing is bad and playing live is good, but there’s still something to be said for recording as much as you can in real time. Digital audio giveth, but it taketh away.

In honky-tonk songs like “Bump Wood” and “Husbands and Wives,” the drums swing in the tradition of Merle Haggard. That’s rare these days.

Yeah, there’s no premium put on swing anymore in most modern country music. Heck, rock used to roll, and to me that means swing. Maybe music didn’t get helped by modern conventions we take for granted now, like click tracks. Didn’t Brian Wilson say headphones and electronic tuners ruined music? [Laughs.] I’m glad it swings because we tried. Jack [O’Dell, Kirchen’s drummer] will be very pleased to hear that. Although Jack is younger and grew up on Led Zeppelin and skate punk, his dad was a drummer, so Jack heard Ray Charles records when he was a kid.

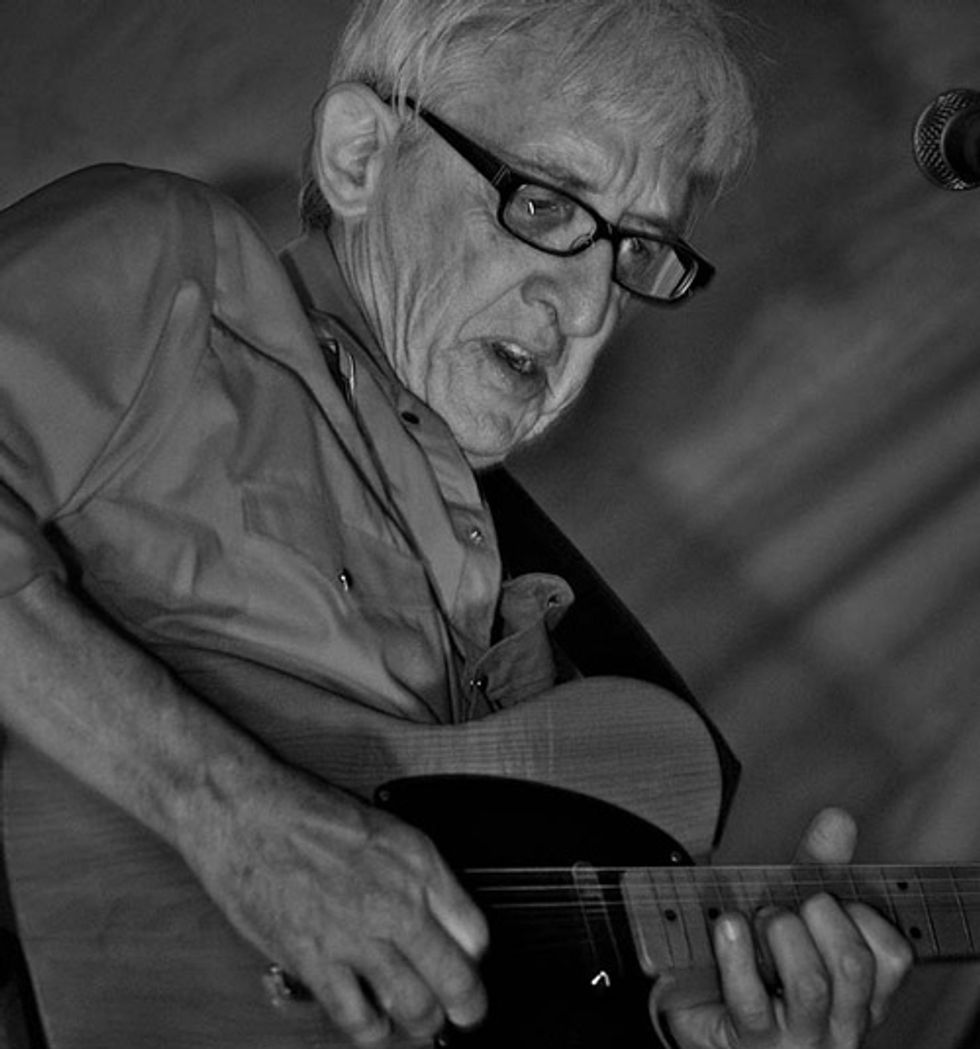

“My advice to anybody is to grab that guitar, get up on that stage, and just try not to suck,”

says Kirchen, shown here at a show on September 12, 2010. Photo by Chip Py

Did you use a variety of Teles on the album or did you stick to one guitar?

When I made this record, I had two main Teles. One was my beat-up ’59 sunburst Tele I’ve had forever—which at that point had Joe Barden pickups in it. The other is a Tele made for me by Eric Danheim, from Big Tex Guitars in Houston. Eric is the guitar player in the Hollisters, and he assembles and relics Teles. I believe the Big Tex has Jason Lollar pickups, though I have no idea which ones. I’ve never been able to figure that out because Eric doesn’t even know. During the overdub process, I got my hands on a delightful Rick Kelly replica Tele with Don Mare pickups. This guitar is made from 150-year-old pine that came from [film director] Jim Jarmusch’s loft in New York City, after he had it rebuilt. Here’s what’s wild: The neck is pine too, and it doesn’t have a truss rod. The neck is just god-awful huge—over an inch deep from top to back. Sometimes when I go for the “folk” F chord—the one where you grab the low F with your thumb—it’s like, “Where is it? Someone help me with this F note!” So I used those three Teles on the record. I can’t tell you which guitar appears on what track, but that’s the way it goes.

How does the absence of a truss rod affect the Kelly’s sound?

Well, Rick’s rap, which I tend to believe, is that without a truss rod you don’t have that hollow below the G and D strings. Instead, you have a solid piece of wood there, and that produces a fatter tone. More and more, I’m realizing that a lot of tone in any guitar comes from the neck, which I never really gave much thought to until recently. I’ve got two Big Tex guitars, and one has a maple fretboard and the other has a rosewood fretboard— and, boy, they sound different. Now I can really hear the difference in the neck.

Tell us about the baritone you played on Word to the Wise.

Well, that’s the fourth Tele I used on the album. It’s a Fender Baja Sexto owned by [luthier and master repairman] Danny Erlewine, who I’ve known since the ’60s from my days in Ann Arbor. He sold me my first tweed Fender Twin back in the mid ’60s. Why didn’t I keep that one? [Laughs.] But anyway, Danny built the body, and I think Fred Stuart [formerly of the Fender Custom Shop] made the neck. I used that a bunch on the album. I also used a Danelectro baritone in England, because I didn’t have the Baja with me.

Do you tune your baritones B–B or A–A?

I tend to tune it A–A, but I’ve done both. On my prior record [Hammer of the Honky-Tonk Gods], I had it tuned Bb–Bb for a song that was in F.

How about amps?

I brought my Talos amp to England and I used it exclusively on the rhythm tracks, as I recall. It’s a dual-6L6, 1x12 combo made by Music Technologies in Springfield, Virginia. It’s a neat amp. When I got home, I used the Talos for the overdubs, as well as a ’68 silverface Deluxe Reverb and a TV-front tweed Deluxe. The ’68 Deluxe has been beefed up by Pete Cage [of Cage Amplifiers], who put in a slightly larger output transformer and reconfigured the amp for 6L6 tubes.

I’ll tell you a funny story about my Talos. When I fly, I surround it with bubble wrap and tote it in a soft-sided suitcase. While I was over in London tracking, somebody told Mark Knopfler about my Talos, and he was interested in hearing it. I’d never met Mark, but I dragged the amp over to his studio so he could try it out while he was working on his most recent album. On my way to Heathrow to fly home, I had to swing by his studio to pick up the amp. I knew I was going to have to pay the $125 overweight shipping to get it home, so I thought, “Why not fill the amp with laundry?”

Now, Mark insists on helping me carry the amp down from the studio. I tell him, “I got it, Mark,” and he says [adopts a British accent], “No, Bill, please let me carry the amp.” So we get down to the sidewalk, where I’ve got a car waiting, and I say, “Okay, I’ve got it from here.” But again Mark insists, ”No, let me help you.”

So he’s holding the case open with the amp in it, and I’m trying to force my plastic bag of dirty laundry into the back of the amp. Well, I’ve been in England for three or four weeks, so this bag just won’t fit in there. Finally, there’s nothing for it: Mark is kneeling on the sidewalk, holding the case, and I have to take my dirty underwear out of the bag and shove it into the back of the amp. I say, “So, Mark, is this how you travel?” And he goes, “Not anymore.” And I say, “So watch and learn, Mark.” [Laughs.]

Mark is a great guy, just lovely. He also has the most spectacular studio I’ve ever seen—by a power of 10. Everywhere you peek, there are vintage guitars and amps, 16-track tape recorders, ribbon mics—all kinds of astonishing gear. While I was there I met [Knopfler’s second guitarist] Richard Bennett, who I’d never met before. He was very nice too.

Are you particular about speakers?

Yeah, I’m really mad for these Jensen neo-dymiums now. I used to use the Jensen reissues, but then the neos came out and they work even better for me. I think it’s because they have a flatter frequency response. Whatever it is, I like it. I occasionally use an original Jensen C12N, and my ’68 Deluxe has an even older Jensen that Pete Cage put in it for me. But, by and large, the Jensen neo is my speaker of choice.

“Shelly’s Winter Love” has deep, throbbing tremolo. Does the Talos have tremolo or are you getting that from the Deluxe?

No, the Talos doesn’t have tremolo. During the tracking sessions over in England, I got my tremolo from one of those $29 miniature Danelectro Tuna Melt tremolo pedals. I love those things. It gives a little gain boost, which is handy. For the overdubs back home, I used my Deluxe’s tremolo.

Did you use other pedals on the record?

I used a Talos overdrive pedal called the Ass Bite Overdrive, of all things. It has four knobs—a Gain knob and a Volume knob, plus one knob for Ass and another for Bite. There you have it. I ask you, what else could they call it? It’s a neat overdrive that can be very transparent. Sometimes I’d use it for a little boost, and sometimes I’d crank it up. I wish I could tell you what songs have the Ass Bite and what songs have an amp turned up to 10.

Kirchen at Woodrow Wilson Plaza in Washington, D.C., July 7, 2006, with his Barden-equipped

’59 Tele. Some 10,000 gigs ago, the guitar sported a sunburst finish. Photo by Mark Jonas

In “Arkansas Diamond,” there’s a phase shifter on your guitar parts. Did you use a pedal for that?

No, I didn’t add that myself. The producer, Paul Riley, put that on after the fact during mixing. When I first heard it, I was slightly miffed. I thought, “What’s that all about?” But then I realized it’s really a nod to the great Waylon Jennings and his Maestro phase shifter, so now I heartily concur. What the heck—if it was good enough for ol’ Waymore, it’s good enough for me.

The phase shifter really accentuates the boom-chuck palm muting you’re doing on the bass strings.

Yeah, yeah, yeah—I know what you mean. It’s a cool sound, like that hollow sound they used to get out of Dano tic-tac basses. It’s a real quacky tone.

When you hit the two solos in “Man in the Bottom of the Well,” you conjure a little of that modal, Summer-of-Love guitar sound.

There is some of that, I know. What came over me? It’s almost like I had my foot up on the monitor and was whipping my hair back and forth. Actually, in ’67 it was more about standing there glaze-eyed and slack-jawed. It was fun to play those solos.

There’s even a hint of Mike Bloomfield.

Oh, I would hope so. I used to see him back at the Keystone Korner in San Francisco. Mike and my wife were friends, and he used to come by to hear the Airmen when we first moved to town.

Toward the end of the second solo, it sounds like you’re using your Tele’s tone pot to get a wah sound.

Yeah, that’s exactly what I did, tone-pot wah. My little finger was honkin’ away on the tone knob— a little something extra for the people. I’ve got the control plate reversed on my Tele, with the tone pot located in the middle of the plate.

For tone-pot wah, do you get fussy about capacitors in your Teles?

No, I don’t. If the tone-pot wah isn’t working or if my volume swells don’t work on one guitar, my tendency is to grab another guitar [laughs]. I’m utterly clueless about that. I know both the capacitor and the pot’s taper play a role, but now you’re hearing a guy talk well beyond his knowledge.

Your main Tele has a Vintique neck-attachment system with threaded metal inserts and machine screws that, in the past, enabled you to easily remove the neck when you flew to a gig. Do you still do this?

When I first started going to England years ago, I carried my guitar in a Land’s End briefcase. I would unscrew the neck, put the body in the briefcase—it fit perfectly—and stick the neck through the umbrella loop on the canvas bag. Maybe if I wanted to be formal, I’d stick a sock over the peghead. I quit doing that after 9-11, because I worried that airport security might not let me take a guitar neck on the plane. They might consider it a weapon. So I haven’t had the neck off in a long time. Nowadays, I fly Southwest in the US, and they always let me carry on a guitar. Flying to Europe, I haven’t had a problem bringing a guitar on the plane in quite a while.

Do you have favorite mic’ing techniques?

In the studio, I leave that to the engineer. But when I’m recording at home, generally I’ll position a Shure SM57 in front of the speaker cone, at a slight angle and a little off center. I’ll also put an AKG 414 a little further back to pick up some room sound. When recording acoustics at home, I’ll use a 414 and a couple of Russian Octava condensers—inexpensive but really nice small-diaphragm mics I got 12 or 13 years ago.

Tell us about your strings and picks.

I use Curt Mangan strings exclusively. I string my Teles with either the stock .010 set or a custom gauge that’s .0105, .013, .017, .026, .038, and .048. On that set, the B, G, and D are the same as a normal set of .010s, but the bottom two are a bit heavier and the top E is slightly bigger. The .0105 set is what I used on most of the record. On my Martin 00-18, I use Mangan acoustic mediums. Also, I use yellow .73 mm Mangan Curtex picks. The material is a dry plastic with an almost powdery finish, and they come in a standard shape. That gauge is between a medium and a heavy pick.

What do you like about Mangan strings?

The whole thing about the Telecaster is the continuum from fat to bright. Where I hear the difference is in the wound strings. To me, they have a nice cross between a bright twangy sound and a full round tone. You know how some strings are so twangy they almost sound like they’re out of phase? That doesn’t happen with Mangans. Also, I don’t get those quality-control problems with his strings—I don’t put on a set and then have one string that’s horribly wrong for some reason. I’ve been playing Mangan strings for at least four years now.

You’ve been working professionally for more than 40 years. What advice do you have for guitarists coming up?

My advice to anybody is to grab that guitar, get up on that stage, and just try not to suck. That’s exactly what I do. I say, “I hope I don’t suck right now,” and then I dig in.

Bill Kirchen's Gearbox

Guitars

’59 sunburst Fender Telecaster (serial number 2222), Big Tex Guitars replica Tele, Rick Kelly replica Tele, Fender Baja Sexto with Dan Erlewine body, Danelectro baritone, Martin 00-18

Amps

Talos 1x12 combo, ’68 silverface Fender Deluxe modded by Pete Cage, TV-front tweed Fender Deluxe

Effects

Boss DM-2 analog delay, Talos Ass Bite Overdrive, Danelectro Tuna Melt tremolo

Strings and Picks

Curt Mangan strings (.010–.046 and .0105–.048 for electrics, .013–.056 for acoustics), Mangan Curtex .73 mm picks

Miscellaneous

Shure SM57, AKG 414, and Octava mics

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)