Brendon Small originally set out to be a guitarist—he even earned a degree from the Berklee College of Music—but along the way he changed gears and decided to focus on comedy. “I spent eight years of my life in Boston,” he says. “Four of those were at Berklee, and the next four were across the river, in Cambridge, studying comedy. I studied guitar and then I studied comedy by doing standup in Harvard Square.”

Small’s experiences as a comedian led him to television and his first animated series, Home Movies, on Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim. “That’s how I got into all this TV baloney,” he says. “I was doing standup over there at the Comedy Studio, which is on the third floor of the Chinese restaurant, the Hong Kong. Back in the day it’d be me—Louis C.K. would stop in all the time and do shows. He was just a kid back then, but older than us. And me and Eugene Mirman [comedian and voice of Gene Belcher on Bob’s Burgers] were roommates.”

Home Movies ran from 1999 to 2004, and Small’s next project, Metalocalypse, brought him full circle. “Had Metalocalypse not happened, I still would have been a geeky guitar guy sitting in my room, being very happy with just playing guitar for myself,” he says. But Metalocalypse—a cartoon series about a fictional death metal band called Dethklok that’s bigger (and far more powerful) than the Beatles—made playing guitar front-and-center in Small’s professional life again. Small wrote the music for the show, played all the guitar parts, and, because Dethklok’s lead guitarist, Skwisgaar Skwigelf, was a shredder, Small shredded as well. He was also voice actor for the Skwigelf character and several others.

Metalocalypse was a hit. It ran for seven seasons—the final episode being an hour-long rock opera, The Doomstar Requiem—and the music from the show also proved popular. Dethklok’s first three albums charted in the top 20 of the Billboard 200 and the third release, Dethalbum III, peaked at No. 10, making it the highest-charting death metal album of all time. In addition, The Doomstar Requiem: A Klok Opera Soundtrack made it to No. 7 on Billboard’s soundtrack chart in 2013.

Small took Dethklok on the road, too. His touring lineup included drummer Gene Hoglan (Testament, Devin Townsend), bassist Bryan Beller (the Aristocrats, Steve Vai), and co-guitarist Mike Keneally (Frank Zappa, and many others). Those musicians are featured to varying degrees on Dethklok’s albums as well as Small’s current project, Galaktikon. “I set up a band where, if I dropped my guitar, no one would notice because the guys I am playing with are so good,” Small says. “They are super musicians. They can do anything. If you hand something to them, they will find a way to do it. They’re bred to do it somehow.”

Small’s second Galaktikon album, Galaktikon II: Become the Storm, dropped at the end of August and again features Beller and Hoglan. He is taking it on tour in 2018. “That’s the plan,” he says. “With Dethklok, I put together a really fun live show that was funny, entertaining, visually exciting, and with a band who could play their asses off. So my whole thing is that if I am going to do this, I have to beat my last show by making it cooler and more exciting visually and musically.”

We recently spoke with Small about his daily practice routine, his home studio, his custom axes, and the philosophical parallels between music and comedy.

When did you start playing?

I wanted to play guitar for a long time, and my neighbor—who I am still really good friends with—he had a guitar. He was already playing and he could play power chords, open chords, and he taught me about King Diamond, Metallica, Slayer. He also taught me about Zeppelin, Jethro Tull, and who Yngwie [Malmsteen] and [Joe] Satriani were—so this kid ended up being a big part of my life. He took lessons, so I started taking lessons from the same guy. We were two nerds. We were getting excited about chord theory—trying to get through chord charts. If we learned a new chord, we would try and write music with it.

TIDBIT: All the tunes for Small’s second Galaktikon album were demoed in his home studio: a converted two-car garage where he’s always got his Marshall miked

up for recording.

But most of all, I was one of those suburban kids with instructional videotapes. I had Paul Gilbert’s Intense Rock Sequences & Techniques, which was really important if you wanted to shred and learn alternate picking and three-notes-per-string stuff. That was a staple in how to play fast guitar for my generation. We didn’t have YouTube when I was growing up, so you actually had to get a physical copy of one of these tapes. That was an important part of understanding technique—seeing real players play well.

Yeah, there’s no substitute for seeing what the hands are doing—and how.

Exactly. It’s funny, you can watch a lot of guitar players who play really well but look like they’re uncomfortable playing. Other people, they’re so relaxed it looks like they’re cutting butter with a hot knife. That’s the kind of player that I wanted to be. Me and my friend had a very healthy competition in both theory and technique—who could do something the other kid couldn’t. We would drive each other nuts. If he could do something I couldn’t, it would make me upset. If I could do something he couldn’t do, he’d lose his mind because I had been playing for less time. It’s nice to have those kinds of relationships. They’re kind of antagonistic, but they’re also helpful in the long run.

What did you eventually study at Berklee?

My major was professional music, with a concentration in performance and composition. I was taking a lot of theory, writing, arranging, and getting deeper with harmony classes and stuff like that. Performance just means I took a million different guitar labs—from country labs to fusion labs. There were actually advanced prog concepts classes where we’d learn about Gentle Giant and Kansas and shit like that. It was really fun.

Were you required to study jazz at all?

My jazz playing is something that I don’t know that I would do in public. As a comedian, I think I would do it in public to get a good laugh [laughs]. Something that I keep working on every day is playing over changes. There are big, long moments where I don’t consider that stuff—where I am working too hard with other things—but whenever I have free time with a guitar, I like to go back to finding cool stuff to do with altered scales over changes, two/fives, and stuff like that. My jazz stuff is very limited, but I get it.

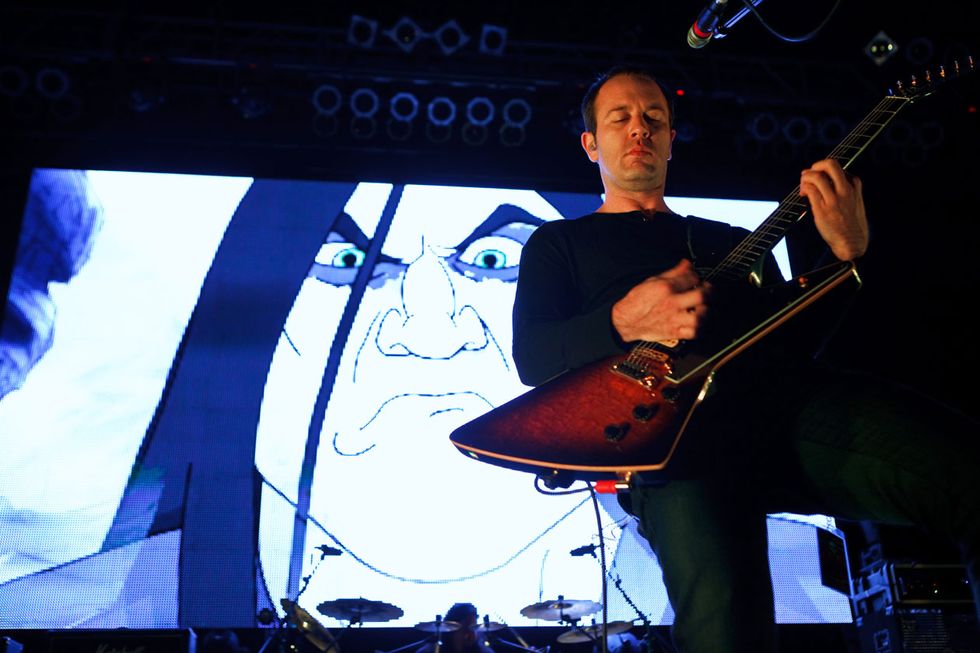

The leap from the Cartoon Network’s animated Adult Swim to the actual stage proved a fairly easy one for Small and his coterie of go-to players, who’ve been performing at clubs, theaters, and festivals since late 2007.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Do you have a daily practice routine?

It changes, but I do play every day to keep my fingers in playing shape. The weird thing about Metalocalypse and me becoming more of a musician, parallel to my comedy career, is that—had Metalocalypse not happened—I still would have been a geeky guitar guy sitting in my room, being very happy with just playing guitar for myself. I buy lessons from people still. I’ll get, like, [U.K. fusion guitarist] Tom Quayle lessons and work on little tongue twisters and things like that. I am always working on getting my legato smooth, getting my economy picking a little more articulate and a little bit more rhythmic. You still improve, no matter how many years you have of playing guitar. Even now, I see little demarcation points of, “This is shit I couldn’t do a year ago but now I can.” Through the last decade of all this TV guitar stuff, it’s forced me to have to get better. You learn very quickly from your first record that all those Paul Gilbert licks and all that stuff that I was working on—you run out of licks very quickly. You can hear that first record I did and it’s like, “There’s a Paul Gilbert lick … there’s a Yngwie lick … there’s a thing Marty Friedman must have done at some point.” You run out of licks and all you’re left with is your sense of melody and your ears. That’s where it starts getting fun and exciting. You start pushing things and thinking melodically, as opposed to lick-wise and staying with your bag of go-to tricks that can start to sound boring.

Do you think your playing has gotten more musical over the last 10 years?

Without a doubt. And that’s because I exhausted the licks in the first two bars of the first record. You’ve got a choice to think, “What is interesting? What is cool? What is your concept of the ultimate guitar solo?” I have to go back to my heroes. I have to think of the people who inspired me and analyze what they did and how they did it.

get a physical copy.

To stand back, look at it, and say, “Is it worthwhile having a guitar solo in this song? Is this advancing the song?” Or in terms of Brian May—who is one of my guitar heroes: He would build a song inside of a song. But sometimes, doing Dethklok and Metalocalypse,I had to force myself to play difficult-to-play guitar parts here and there, because I wrote the character to be a shredder. Had I not made him a shredder, I would not have had to study that stuff as much.

So the character forced you to play faster even if you felt a song might call for something slower or more melodic?

Yes. Exactly. It’s funny, recording and listening to myself forced me into taking what I like about the style of music and what I am bringing to it, and hopefully advancing it just a little bit.

Let’s talk a bit about how you capture ideas. Do you have a studio setup at home?

I converted a two-car garage into the ultimate studio for me: I have an amp closet where I have a Marshall set up with three mics. Sometimes I just use two on the cones, but it’s always miked and ready to go. I have a whole trough underneath of cables that go to my mixing board. I’ll plug straight into the Marshall, send the sound right into my studio monitors, hear a nicely produced guitar sound come through, and I’ll play with that. I’ll turn up to 4 or 5 on my amp and record really loudly, even just for demo ideas. I remember reading an article in some guitar magazine a long time ago where they said, “Don’t have to set up your guitar area—have it ready to go at all times.” There are so many wires and cables and so many headaches and so many different things that can be just fucked up or go wrong. Leave it plugged in. Don’t give yourself any excuse not to make music.

Brendon Small’s Gear

GuitarsGibson Thunderhorse Explorer

Epiphone Thunderhorse Explorer

Gibson Snow Falcon Flying V

Epiphone Snow Falcon Flying V

Amps

Joe Satriani Signature Marshall Head JVM410HJS

Effects

MXR EVH 5150 Overdrive

JHS AT (Andy Timmons) Signature Channel Drive

Electro-Harmonix Mel9

Line 6 Helix

Boss SL-20 Slicer

Dunlop Dimebag Cry Baby from Hell

Dunlop EVH95 Eddie Van Halen Signature Cry Baby

DigiTech Whammy

Strings and Picks

Dunlop Nickel Wound sets (.013–.056, with a wound G)

Dunlop Ultex 1.14 mm picks

I have that set up, and I use Pro Tools HD. I’ve got a board in there. I’ve got mic preamps—some APIs and some BAE copies. I have a [Shure SM] 57 and a [Sennheiser MD] 421 and a Royer [R-] 121, and I have a little mixer that I’ll use to blend all those sounds. If I want a little more top end or a little more bass, I can mix that in. But I usually keep it pretty similar.

Which Marshall are you using?

I’ve used a lot of different Marshalls over the years, but for this record I messed around with a few different amps and landed on the Satriani Marshall—the modded JVM that Satriani has [the JVM410HJS]. I had gotten a few new distortion pedals when I first started making this record in 2015, and the clean channel really worked well with all of them. It has a good fundamental sound underneath everything. I used the MXR EVH [5150 Overdrive]. I felt like I got a different sound out of that, which was warm for distorted rhythm parts. We did a lot of cool EQ-ing on the guitars and changing things in post [-production], too. I’d forgotten that that’s a really important part of recording a record: First you have to get a sound you’re comfortable with, but you don’t have to commit to it—you can move your EQs around and dial it in after the fact.

What kind of tone sculpting did you do?

What naturally happens in heavy metal—because you’ve got left and right [-channel] guitars that are at full distortion playing rhythm all the time—is that those frequencies are going to compete with what the bass is doing, and also what some of the brass is doing on the drum kit—like the hi-hat, the crashes, or the Chinas. So a mixing person’s first move is usually to start scooping mids out of the guitars, but I don’t like that sound—not these days. I want a fat sound. I want a frown-curve EQ more than anything. I want to make sure I have cymbals and all that stuff, but what I’ll try to do is add the right frequency of the mids back in. I try to make sure my leads sound warm and vocal-like—and, hopefully, violin-like.

I read somewhere that you always practice to a click track.

If it’s not a click, it’s some track with drums on it that I am playing over. It took me a while to learn that if you’re not practicing rhythmically, you’re not doing anything.

Do you use a click track while writing, too?

Sometimes you’ll be sitting there, hunched over your guitar, and come up with something that doesn’t have a click track or anything. What I’ll usually do is open my iPhone, record it, and describe what I am doing to myself so I remember it. But usually the way that I write music is, I have those riffs that I’ve collected, then I bring them into Pro Tools and either drag in some drums that are somewhat in the ballpark of what I’m hearing, or just a straight click. The way I look at Pro Tools is that it’s like a big note pad—you’re scribbling all over it, making all these notes, and at some point you circle one of the notes and go, “This is a cool idea. I’m going to develop it. I’m going to hold onto this piece because it moves me for some reason.”

YouTube It

Brendon Small displays his bona fide metal chops at this March 2013 guitar clinic, performing his Dethklok composition “Thunderhorse” on a Les Paul.

That’s the cool thing about writing music. You can’t really do it the same way with comedy, but with music you can be the composer and the audience for it at the same time. If it is moving you, it might move somebody else. Not always, but sometimes. In fact, more often than not in my history, the things that I like are the things that the audience tends to like, too, which is a nice place to be. But it doesn’t work that way with comedy all the time. Just because you laughed at a joke doesn’t mean anybody else in the world will find it funny. That’s the brutality of comedy, which is fantastic.

Does that brutality apply to music, too, or is music more forgiving?

Music is not about surprising people. It is about some kind of weird, subconscious mind-hook that brings you a little bit closer to a song. It alters your mood, hopefully, in some way that makes you feel differently than you did before the song was playing. That’s my very reduced idea of what music should be. With comedy, I’m surprising them. Hopefully, it comes to this place where I’ve set up this thing and then I pull the rug out from under you. I surprise you with something you didn’t expect me to say. That surprise wears off if you listen to a joke more than once. With music, you can learn to enjoy the song more the more you hear it. Did you ever have one of those records where you listen to it and think, “This is really interesting but I’m not sure about it”? Then you listen to it a few more times, and it starts gaining in listening. That’s what I am after—that you uncover a subtext as you continue listening. You can still listen to your favorite song and get something out of it, even though you’ve been listening to it forever. But with humor, it dissipates. It reduces each time you hear a piece of comedy. You still appreciate it like crazy, but you’re not emotionally tricked anymore.

Small’s World of Guitars

Brendon Small’s late animated television series, Metalocalypse (which ran from 2006 to 2013 on Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim block), has a cult following with guitarists for many reasons. The humor, often tied to stereotypes and inside references only true guitar nerds will get, is spot-on. The animated segments showing guitar playing are depicted realistically and accurately. And the guitars themselves are often recognizable models faithfully rendered. Some are even based on Small’s signature Gibsons.“Since I’ve kicked my foot through the door at Gibson,” Small says, “I keep trying to get them to build more guitars for me and to release more guitars. Because who wouldn’t want to do that?”

Small has four epically named models. The limited-edition Thunderhorse Explorer is available in both Gibson and Epiphone versions, as is the Snow Falcon Flying V. “I have prototypes for other Explorers, too,” Small says. “One of them is called the Snow Horse, which is an all-white Explorer. I have two of those: one with a super-shreddy neck and one with a super-fat neck. The main experiment I did with those guitars was removing as much paint as I could—maybe one coat with a little bit of a light burst dusting on it. The reason I did that was because my first Thunderhorse, a silverburst Explorer, wasn’t lacquered—it has, like, a satin finish. It didn’t have that much paint, and it wore off the back playing it live. At some point, we played a gig in Tennessee and the whole luthier team of Gibson guitars came out and watched the show.

Before we went on I said, ‘Why do I keep coming back to this guitar? Why does this guitar sound better than these ones with lacquer on them?’ And they said, ‘It’s the paint. The paint compresses your sound. It looks cooler. That’s why people want them. They want these glossy, shiny guitars. But the ones that sound better have less paint.’ That totally made sense to me. The wood needs to age, it needs to dry, it needs to go through a cycle, and we stop that process when we put a ton of lacquer on. So part of the experiment with these prototypes is that they have less paint.”

But not every design decision was tonal. Some—like the reverse headstock on the Snow Horse—were made for looks alone. “There is no advantage whatsoever,” Small says about that design. “In fact, it is more difficult [to tune]. But I think it looks neat and reverse headstocks are cool. It also makes sense with the whole shape of the thing: The Explorer has these cool angles and this adds one extra angle.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)