|  |

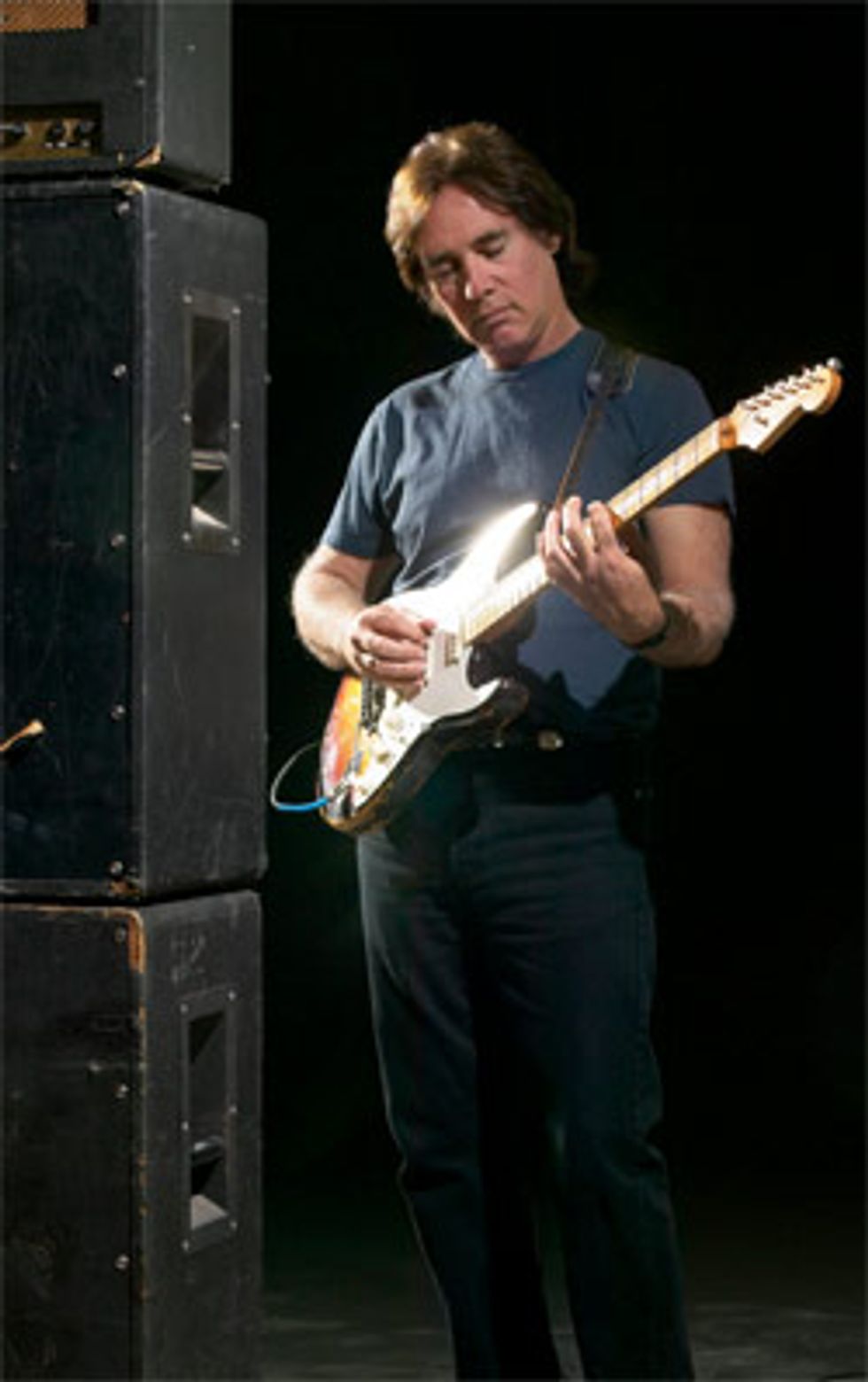

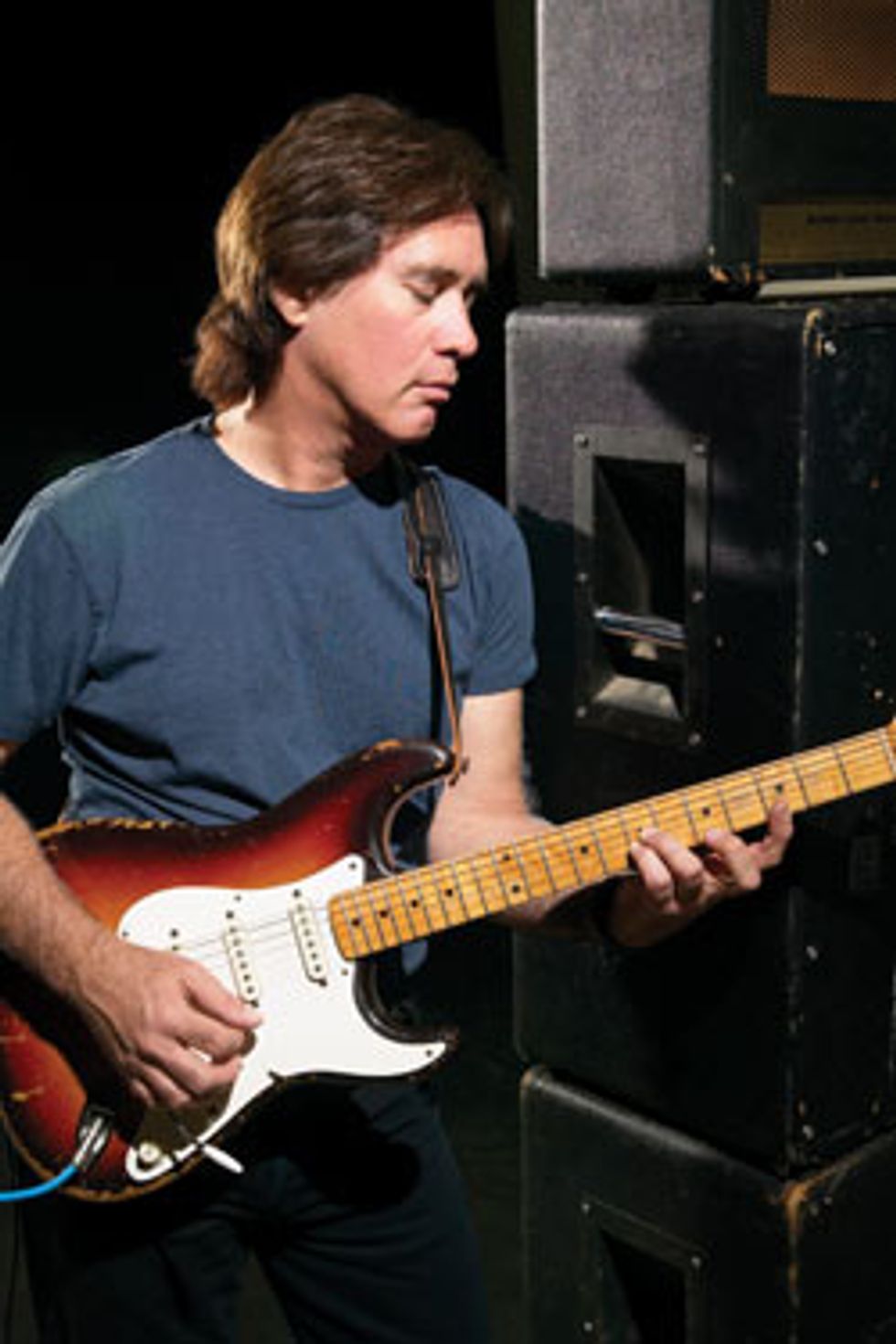

I caught his gig at Hollywood’s legendary fusion hang, The Baked Potato. I heard an eye-bulging fusion of great tunes and styles and that made me want to run home and practice. Verheyen uses the kind of gear that makes guitar freaks need a drool bucket. He uses a mix of vintage amps and guitars married with modern technology—to great effect. Verheyen has the coolest toys. When he agreed to this interview, I knew this was going to be the perfect opportunity to pick the brain of a great virtuoso. He also turned out to be one hell of a nice guy.

What in your mind distinguishes you from other guitarists who put out records with chops for days?

The problem is that there are so many guitar players nowadays that love to use their home studios and spend hours and hours on their solos. I’m an old school guy sonically. I’ve got to use a real studio. You never listen to your amp with your ear down near the amp. You listen to your amp in the room. The best studios in town, like Capitol Records and Sunset Sound and some of these old school places, have amazing rooms. We mic the amp, but we also mic the room. That’s the sound of the guitar and that’s what I want to hear. I’m not a home studio guy. I pretty much just do little demos for myself on an old hard drive recorder, and mic amps and mic acoustic guitars and work out parts, so I rarely have to use a real studio.

So instead of my records costing $5000 to $6000, they cost $25,000 or $30,000. Which is dangerous nowadays in this climate where people aren’t buying CDs—they’re downloading. But that’s ok, too.

The sound on your records is very organic.

I never use plug-ins, and I always mic an amp no matter what. I like to mic it through some of that old API gear that they have at Sunset Sound, but I’m paying two hundred bucks an hour (laughs) so it’s a little dangerous. You want to be able to listen to it five to ten years from now and say, “Man, this still holds up,”

whereas that plug-in stuff may not.

When I go into the studio, I have four to five hours to get this tune completely in the bag. That means the 12-string part, the Gretsch part, the SG part, the two acoustic parts and the solo. The modern art of the guitar records is in the orchestration, because at some point everybody’s got monster chops.

I was listening to Greg Howe’s new record and thinking, “Oh man, this guy’s chops are insane!” There are a lot of people on a level that’s pretty high in terms of that. Now it becomes, how do you layer? How do you orchestrate? My concept has always been, “How do I pick who’s going to be Frank Sinatra? Which guy is going to have that main voice?” On those Frank Sinatra records the whole orchestra comes in and it’s beautiful. There’s this huge level of glorious sound. Then Frank comes in and it’s even more glorious!

So when you’re orchestrating all the guitars you have to figure the rhythm part is going to be this clean Strat, but I’m going to back it up with this acoustic. I’ll put the Strat in the middle of the two acoustics to give it a little more sonic girth. Right in the pre-chorus this Tele has to come in with a little hair on it. When the chorus hits I’m going to put the Les Paul here and the SG here through little amps, and they’re going to play the same unison line. Little amps are key because they can give you that cranked tone. When the solo comes in, that’s a 4x12 in the middle of the room with a mic far away and you get this big huge sound. You can hear the room, and that’s really important.

1969 Marshall 100-Watt head, 1964 Fender Twin, 1963 Vox AC30 and two THD 2x12 cabs. |

In the eighties, just like everybody else around 1981, I met Bob Bradshaw. So I got the big rack. That rack grew and grew, and then there were two racks, an amp rack and an effects rack. One day in about 1989, when all that stuff was going strong, I remember plugging my seafoam green Strat into one of my Fender Princetons and thinking, “You know what? This sounds better to my ears than $50,000 worth of rack gear.” In those days we were listening to the sound of the reverbs and the delays and the choruses. When you turned all that stuff off, the sound of the basic guitar through the rig was kind of sterile. I realized that the marriage of a great-sounding guitar with an amp is very important. I had a Vox AC30 and some Marshalls

and stuff like that and I thought, “Maybe I can use these things.”

It started to come together with an A/B system. I would say right around 1990 I started putting together that kind of clean and dirty rig. I remember talking to Allan Holdsworth and he said, “You don’t play clean and dirty out of the same speakers do you?” And I said, “Yeah.” He said, “How can you do that? I want a real papery warm sound from my lead tone, like Celestions. From my clean sound I want something a little more bright and pingy.” Then I thought, “Well so do I!” That’s what kind of started me thinking down the road of having two separate rigs.

At one point I was playing a show at Billboard Live in Hollywood, and I had my rack stuff and the entire band’s show was programmed in. I just had to go to number one, number two, etc. Somebody walked by the power source and kicked the cable and it came out of the wall. It wiped out all ninety-nine programs! So I’ve got ten minutes until show time, and the other band had a Fender Twin. I thought, “I’ll just pull out some pedals, plug into this Fender Twin and go for it.” Really, when you get into all this changing of parameters of each sound, the only person who knows it is you, unless it’s super radical. I realized at that point that it’s better to have two amazing sounds than ninety-nine okay sounds.

That rackmount preamp/power amp period was sometimes an eight, but never a ten. My two favorite clean sounding amps are the Fender Twin and the AC30. I get all this nice midrange and fatness from the Twin. With the AC30 I get all this high-end sparkle. As a stereo pair it’s pretty cool.

Dr. Z SRZ-65 head, with Carl's rack. |

What I do is come off the A/B pedalboard, and for the clean I’m going through one pedal. It goes into a Robert Stamps reverb unit, which he made custom for me back in 1997 when I was about to do a Supertramp tour. I needed spring reverb, but in rack form, and he did that for me. It comes out of that and goes into a stereo chorus, but I almost never turn it on. When I do, it’s very subtle. That comes out in stereo to the left and right inputs of a Lexicon MPX 100 Stereo Delay. I use that ping-pong delay just to give myself some imaging on stage. I’ve got a few settings for various tempos, and all my rack effects are before my clean amps. For the dirty sound, I come off the B-side of the pedal board after going through the three distortion pedals and go into the Doctor Z head. It’s a replacement for my old Marshall. They’re becoming $5000 to $6000 for those Plexi heads. Doctor Z made it so that if you turn the master volume all the way up it’s out of the signal path. It’s basically acting like a non-master volume amp using the power tubes to the fullest. Then I come into one of those THD Hotplates. That has a direct out—I feed that to a cabinet—and it also has a line level out that I feed into a Lexicon PCM-41. It’s a line level reverb, and the only way you can get into that is by turning the speaker out into line level, which the Hotplate does really well.

The switching is seamless.

An A/B system like that is going to be organic, whereas if you do channel switching or MIDI or any of that stuff, it cuts off. That little millisecond is not organic. If I have a rhythm part going and I’m singing, and I feel like slamming in a little lead line, the rhythm part hangs over in the air while I switch. There’s no pop or anything with those Lehle foot switches.

Carl's pedalboard. |

Yeah, there’s a really nice distortion pedal I’ve been using called the Cream pedal by Andy Fuchs of Fuchs Amplification. It’s kind of a cross between a saturated Fuzz Face type of pedal and a Tube Screamer. It’s somewhere in the middle, which is nice because I find Tube Screamers sometimes aren’t saturated enough to get that creamy tone. Fuzz Faces are a little hard to manage for me. They’re a little out of control. I’ve been using that quite a bit lately.

Doctor Z recently got me a new Carmen Gia head. That’s a really nice head. It’s only 18 watts, but for recording or a small blues gig it’s great. I’ve been able to use that head to get the sound I’ve never been able to get before, real beautiful sounding.

How did you become such a successful session cat? What separates you from other guitarists?

I looked at the guys who just did record dates. They were maybe non-readers. Then I looked at theses other guys who seemed to be able to do everything… records, movies, jingles, TV, all that kind of stuff. The guys who can do everything get a lot bigger piece of the pie. To me the number one requirement for that was a thorough understanding of the ornamentation of the styles.

When you really get down to it, blues, blues-rock, rock, country, country-rock, bluegrass, jazz, heavy metal, be-bop, all these different styles of music use the same twelve notes. The only difference between the jazz guys is how they ornament the style. They’ll play a certain feel so it’s a rhythmic ornamentation. They’ll play a certain choice of notes so it’s a harmonic thing and a sonic thing. You take that be-bop style of Charlie Parker—it’s really in many cases the mixolydian mode. Then you go to these blues guys like B.B. King. He’s also playing the mixolydian mode, along with minor pentatonic and various things, but so are the jazz guys. So it’s the phrasing and what I call the ornamentation of styles.

I had an awakening one day around 1980. I’d been studying jazz really hard, practicing five to eight hours a day for maybe six to seven years to try to be able to play through changes in the style of Wes Montgomery, Pat Martino, Pat Metheny and all those guys. I wanted to be a jazz guy. One day, I’m driving my car and I hear this Joe Walsh solo on the radio. It was from The Eagles’ tune, “Those Shoes.” It was just a soulful solo. I think he was using a voice box. I had to pull my car over. The state of the art of rock guitar has come so far. It made me think, [laughing] “This is the music of my people!” It made me really think, “I could play twenty-six choruses of ‘Stella By Starlight,’ but who cares? I really like this.”

Come to think of it, I love that Chet Atkins stuff I was hearing the other day. And I really like the way my friend plays classical guitar, and I’d really love to learn some of those Bach pieces. And I love the way Albert Lee plays. I need to get into everything. It made me come to realize that if you dig it, you must learn it. I just want to be a great guitar player, and not a great jazz player—not necessarily a great one thing or another. I think that really helped me in the studios.

Give me an example of how this works for

you in the studio.

I come into a session on a country thing, so I pull out this great Fender Tremolux amp I’ve got, and plug my Telecaster in and get the perfect country sound. Then the producer says, “Ya’ know, I think it’s a little too country. Can we rock out?” So I say, “Yeah.” So I get a Strat and play through a THD head that has some crunch to it. So the artist says he wants to go more acoustic and he wants to take it up a step. So now we’re in a different key and we’re thinking bluegrass or folk-rock.

If you’re the hat-wearing, boot-wearing, country picker guy, once they start changing it you’re sent home. That day is over. They need different guys because that country guy can only play one thing. Anybody who wants to be successful in the world of producers and songwriters really needs to have all that versatility. It’s even more important than reading, unless of course you get into movies.

You seem to embody those styles a lot more than what I hear from people coming out of academia. You sound like the real deal.

You seem to embody those styles a lot more than what I hear from people coming out of academia. You sound like the real deal. You’ve got to separate your artistic career from your sideman career. Your sideman career is about you being a well-listened craftsman. I was called into a session once where they said, “I need that ZZ Top thing.” That’s Billy Gibbons playing a Les Paul, probably through a little tweed Fender amp. Pinch harmonics… a Texas shuffle is very different than a Chicago shuffle so the sound adjusts, the feel adjusts and here’s my impersonation

of Billy Gibbons. That is being a well-listened craftsman, as opposed to an artist. I separate the two in order to make a living. When you are a sideman you’ve got somebody else’s musical vision that you’re trying to bring out. When I’m making my own records it’s my musical vision.

The styles come through in your solo work.

I hear all that country stuff in my own playing, the jazz stuff as well as the fusion of rock and blues. It’s all part of the expression of the whole. With the well-listened craftsman, you’re kind of like a plumber who looks under the sink and says he needs a 5/8” wrench.

Knowing your guitar tone history is just as important as knowing the fret board.

Every real serious student of the guitar is also a musical historian. You think back to those old records and you know what they played. Seymour Duncan can name every guitar from every track from the fifties, sixties and seventies. He knows every pickup. He knows it all.

What do you do to further your craft in terms of practicing?

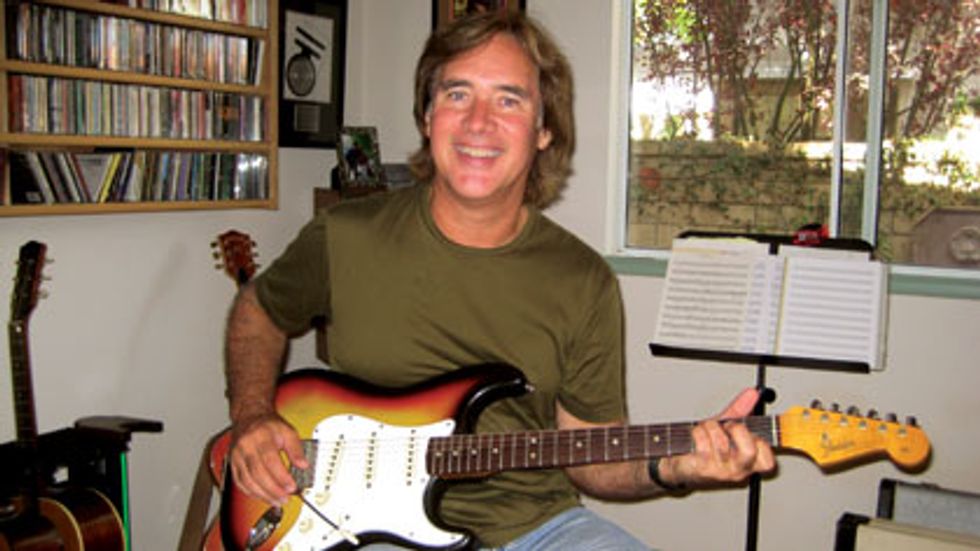

I’m a serious practicer. To me, practicing is where I find my center as a person. If I go a day without practicing, I feel useless. I don’t feel like I’m doing what I’m here to do. I don’t feel like I’m on the level of where I want to be. To practice, I’ve always kept a lick book. It’s an ongoing musical diary that’s always on my music stand.

I’ve got lines for Emaj7th chords, harmony lines, pentatonics in D minor, chord voicings and anything that comes to mind. I’m always writing stuff down. I’m getting ready to do a DVD, so I’m writing five minor, five dominant and five major lines. I have old lick books that are completely full of lines. I’ve transcribed Brent Mason’s “Hot Wired” and then start working on ideas from that. It’s a great way of practicing. I’ll say, “I need a line in F# minor that starts on the low F# and ends on the high C#.” I’ll come up with something new and original, then write it down. Then I’ll transpose it into a major version, and then a dominant seventh version. Then I’ll practice it… to see if it fits. Then I’ve got new material—or I could go back ten pages. I can try it again and it might lead me to new stuff.

You’ve discussed your lick book on your Intervallic Rock video. It’s invaluable.

My personal style is a direct result of the lick book. My intervals are always larger than minor seconds, major seconds and minor thirds. I think in terms of fourths, fifths and sixths. It relates to my lines and my chords.

I would say it’s a key element of your style.

| ||||

People who are full-time musicians run the risk of picking up the guitar after work and relaxing with it. They end up playing the same stuff they play every night to relax. It’s like the glass of wine. They play a lick, maybe a couple of chords, improvise in D major and it just kind of flows along. That isn’t practicing.

Practicing is finding new things or getting the impossible stuff you already know down better.

Improving. Do you play every single day?

Yeah. Not playing for a couple of days would be really bad.

What’s your favorite Strat?

The one you saw me play live is a ’61 seafoam green Strat. It’s my favorite rock guitar.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)