The flamboyant Fantastic Negrito is a self-described “recovering narcissist.” You might have NPD, too, if you accomplished even half of what he has. Since 2015, Negrito has performed at several of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign stops, released The Last Days of Oakland (which won a Grammy in 2017 for Best Contemporary Blues Album), and toured with the late Chris Cornell and Cornell’s supergroup Temple of the Dog. But while he rose to stardom in just three short years, his success was anything but overnight.

Born Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz into a Musilim family spearheaded by an Oxford-educated, Somali-Caribbean immigrant, Negrito is the eighth of 14 kids. His family moved from the East Coast to Oakland when he was 12, and once he arrived, he left home, never to look back. “I grew up in the streets of Oakland and embraced all the culture,” says Negrito. “It was just so ripe and ready to be picked back then. The beginning of hip-hop meeting punk music meeting progressiveness with a taste of hippiness and some gangsta-ism—all into one pot.”

Negrito got caught up in the life of a street hustler, but after a hairy encounter with a masked gunman, he left Oakland for L.A. There, Negrito’s demo tape ended up in the hands of Prince’s manager, Joe Ruffalo, who put him up in an apartment and gave him a stipend. He soon scored a million-dollar deal with Jimmy Iovine of Interscope Records as Xavier, and released The X Factor, an album that he played all the instruments on. At the time, gangsta rap was in vogue and Negrito’s music failed to catch on. Negrito says, “It was this huge record deal and I was supposedly this huge star, which is what I wanted back then, and gosh, four or five years into it when nothing was happening, something really big happened, which got me out of it.”

That something was a catastrophic accident in 2000 that flipped Negrito’s car over about four times and left him in a coma for three weeks. The prognosis was dire. “I woke up from the coma and went, ‘Hey, are my hands okay? I’m a musician,’” recalls Negrito. “I looked around the room and people shook their heads. They didn’t even say I severely damaged both of my hands. They thought I would never play again.”

I think I’m in full recovery though.”

After leaving the hospital, Negrito delved into the underground music scene in South Central L.A.—a world he recalls being inhabited by illegal nightclubs and sheriffs snorting cocaine. During this period, Negrito had a few musical incarnations, which included licensing his music for over 70 films, and recasting himself as Chocolate Butterfly, Me and This Japanese Guy, and Blood Sugar X. He was, in his words, “lost in a beautiful wilderness of sex, drugs, and adventure.”

But he eventually got burnt out and decided it was time to come back to Oakland. He sold off his equipment and left the music business to become a weed dealer. One day his son was cranky, and, out of solutions to satiate the kid, Negrito pulled out a guitar that ended up reigniting his creative juices. No, it wasn’t some closet classic 1958 sunburst Les Paul. Quite the opposite, really.

“It was a cheap guitar from Thailand, and I hated it,” says Negrito. “My friend, who had stolen some of my equipment because he was on heroin, gave me that guitar to try to make up for it. I was trying to sell it but nobody wanted it. So there it was, under that couch for five years. I picked that thing up, man, and looked at my son and strummed a G chord. I looked at this kid’s enjoyment of hearing the strings resonate with that wood. It made me feel so many different emotions—I was a little bit scared, excited—and I could feel the tingling behind my neck. That became the slow walk back to just playing. I learned ‘Across the Universe.’ I thought, ‘I’m gonna play this for my son to get him to sleep every night,’ and it worked like a charm.”

During this time in Oakland, he formed a multimedia collective called Blackball Universe with writer Malcolm Spellman, who soon became famous for the TV series, Empire. “He pushed and pushed me, and that was the birth of Fantastic Negrito,” says Negrito. “I thought, ‘Pick up your guitar and go hit the fuckin’ streets. Don’t ask for help from the major labels, don’t go to the clubs, man. Take that damn guitar and play on the streets.’” Negrito entered and won NPR’s Tiny Desk Contest, beating out around 7,000 entries with his song, “Lost in a Crowd.” This victory marked the beginning of his comeback.

TIDBIT: Although Negrito’s management and label urged him to record his second album in a fancier studio, he chose to stay in Oakland and cut tracks “in the same shabby little room that I recorded my Grammy-winning album in. I just wanted to keep it real.”

“I didn’t even want to do it,” he says. “I was in a collective, which means we vote on everything. I voted against Tiny Desk. I thought it was a waste of time. But yeah, that happened and the rest is history.”

Negrito’s latest release, Please Don’t Be Dead, melds social commentary with heavy riffs, and is one of this year’s most compelling albums.

Did winning the Grammy for The Last Days of Oakland have any impact on how you approached Please Don’t Be Dead? I understand your previous Interscope deal messed you up creatively.

Oh hell no, man. I took a complete detour. Everyone was talking to me about that stuff and I closed my ears. I stayed in Oakland and recorded in the same shabby little room that I recorded my Grammy-winning album in. I just wanted to keep it real. I was like, “You know what, I just want to forget that I wrote The Last Days of Oakland. I wanna come out swinging, man.” What happened to me was, I was in Europe and people would come up to me like, “Hey, what is going on in America?” And I would be like, “Okay, I’ve heard this 100 times.” So I thought to myself, “There’s Nazis marching in North Carolina. I’ll be willing to bet that those Nazis like ‘Johnny B. Goode.’”

I just kept thinking about this, and I thought, “That’s really the power of music, especially American music, which is so rooted in blues.” I call it the “universal riff.” I remember I was in Norway right after I thought that, and I had written “Plastic Hamburgers” because I was going to do a duet with Chris Cornell. He was going to do the third verse—I had written the extra third verse for him to write what he wanted, so I just left it open for him. I go, “Hey guys, let’s play this new song.” I was in a foreign country, and they didn’t know me, and that riff opened up and I’m like, “blues in E,” [sings heavy riff] and it was like, “We got ’em!” I remember thinking, “Damn, the riff, man. That is the unifier.”

Please Don’t Be Dead is definitely riff heavy.

Man, it’s everything. I feel that’s like the spirit of the album: the hope and optimism about what America really meant to the world, and what we brought culturally, musically, and idealistically, in terms of values. I was like, “This is going to be all about riffs, bass guitar, blues guitar riffs, chants.” I wanted everything to be something that pulls people in.

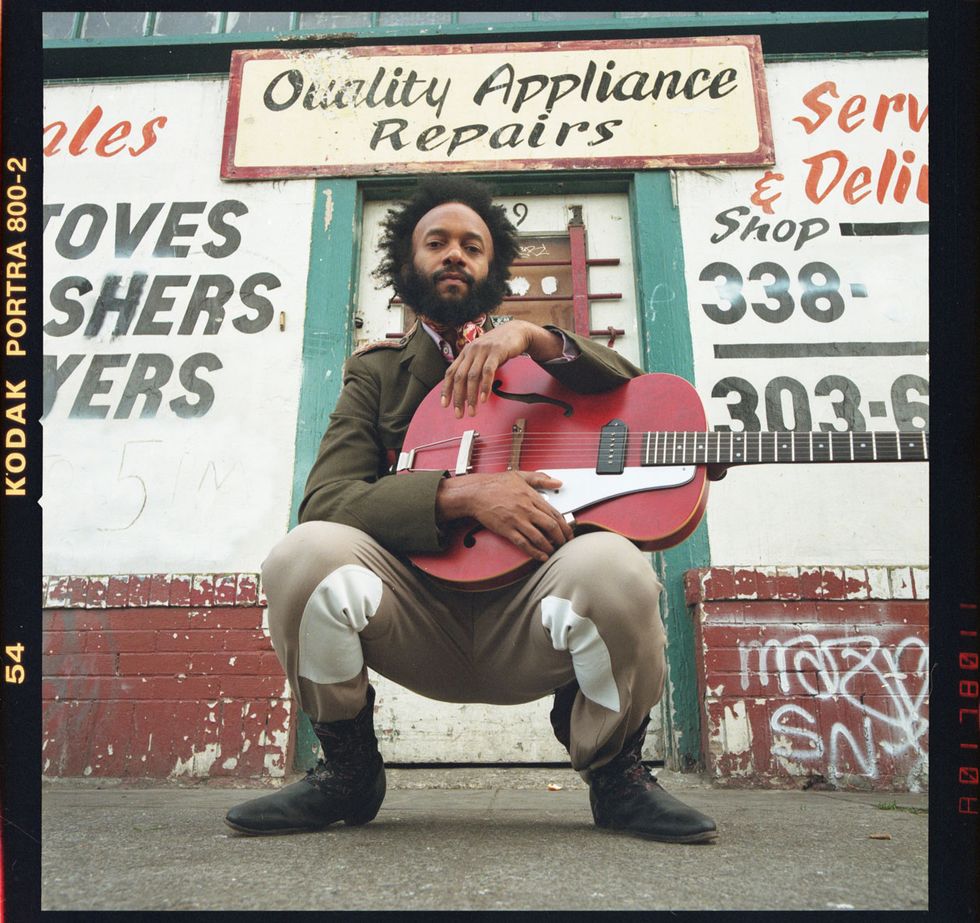

Up against the wall: Negrito was essentially out of the music business, growing and selling pot, when a desire to sooth his infant son with song and a push from his artists’ collective rekindled his career. Photo by Lyle Owerko

I’ve seen videos of you playing, and it seems like you strum with your thumb on chords, but when you play single-note runs, like bass riffs, you use your index finger and pluck up, like a bass player.

Yeah, it’s just so fucked up that I can’t even put into words how I do it. You gotta imagine that I have a hand like this: The wrist won’t move, the fingers move really lethargically, so it’s like someone cut open my hand and poured concrete in it. I call it “the Claw,” and I put the Claw on it and whatever it fuckin’ hits. I understand why they thought I would never be able to play because I can’t really move my fingers. And my thumb doesn’t move. I got about maybe three inches I can move on my thumb. God, if I tried to really do it, it would be depressing, so I’m like, “You know what? On piano and on guitar, I’m going to accept whatever my hand does.”

“A Cold November Street” has a short, screaming guitar interlude from Masa Kohama. Did you influence the direction of your musicians’ performances or did you trust the instincts of your band?

I’m very strange as a producer, because coming from the old original hip-hop sampling generation, what I love to do is I record everybody and then make up what I want to make up. So, I kind of make guitar solos. I’ll patch it together and take the best parts. It’s one of the great things about Pro Tools. I’m pretty verbal about what I want to hear. I’ll be humming and strumming and talking, and I kind of know exactly what I want. I’ve been playing with that guy for so long that he kind of knows me. It’s different for other projects, but for Fantastic Negrito I’m always about less, less, less, less. I want to get to that point in the shortest distance. I’m trying to isolate intensity. I kind of took to blues and all this black roots stuff, and what I loved was the simplicity and the rawness—to have impact with less.

“A Letter to Fear” starts of with an ominous vibe, vaguely reminiscent of Led Zeppelin’s “Dazed and Confused.”

I never thought of that. I love all of that English rock. If I hear great comparisons like that, I’m just happy to be in the same sentence. I remember meeting Robert Plant. He came to see me at a small place in England. Of course, I love Led Zeppelin and everything they listened to, like Skip James. I love it all, man. Anything that’s great, I try to soak up. When I wrote that song, I was on an airplane and I remember hearing about another fucking shooting, I think it was Texas. I was like, “I just won’t get used to this. I won’t let this be something normal.”

That song and “Dark Windows” have interesting chord movements that work so perfectly, yet go to unexpected places.

“Dark Windows” is a song I wrote about my relationship with Chris Cornell. I wanted to make peace with that. We had a very special relationship with a comfortable distance. We did three tours together. It’s just the power of music. That’s what we can go to in a tumultuous time where there’s so much divisiveness. This is what’s going to get us through it, man.

Guitars

Epiphone Hummingbird

Epiphone Masterbilt acoustic-electric

Epiphone Century archtop

Harmony hollowbody

Basses

Fender Precision

’80s Fender Aerodyne Jazz

Rogue

Fender Jazz American Deluxe V (owned by Cornelius Mims)

Amps

Cave Valley Thunderbird 50-watt combo

Fender Bassman

Fender Twin Reverb

Effects

Dunlop Cry Baby

MXR M75 Super Badass Distortion

Strings and Picks

Gibson sets for electric and acoustic (.011–.050)

Gibson bass sets (.045–.105)

Are you primarily self-taught?

As a senior in high school I became interested in music and I’d sneak into UC Berkeley and pretend I was a student. They weren’t so conscious about security back then. I would sit there and listen to what people were playing—they were mostly scales. I didn’t know what it was, but I figured out that you could play Do–Re–Me–Fa–Sol–La–Ti–Do in every key, and I was like, “Wow.”

Was that all by ear or did you watch and mimic their fingerings?

It was all by ear. I didn’t know shit. I just wanted to play. Back then I loved all those early Prince records and I read about him, and it was like he just taught himself. So I was like, “Shit, I’m gonna teach myself.”

You played a lot of instruments on Please Don’t Be Dead.

Well, come on. I write on them but I don’t have anything like Prince had. I’m like utility guy: “I need these tools to paint this picture.” I just got one guitar that I really love playing. It feels different. It’s an Epiphone Hummingbird. There’s something about Epiphone. I mean, I love Gibson stuff, and I record and play with some of it, but the Epiphones just sound more street to me. The Epiphone electric hollowbodies are also really great. They’re good for a guy with 20 percent of his hand. You don’t have to work too hard. There’s one that’s mixed in really low, especially on “The Duffler.”

What basses did you use on the album?

Man, I used about five, six, seven bass guitars. I remember going for different tones and rounder stuff, and more edgy percussive stuff. I used that old Precision bass. I used that 4-string, violin, cheap Korean bass. What is that called? It’s a Rogue. I was like, “Oh, 79 bucks? I’ll take it.”

Gear snobs will usually look down on the cheaper stuff.

It just depends on what you’re trying to do, and I was like, “This is warm, I want this.” I played bass on one track—I used the Rogue on “Transgender Biscuits,” and Cornelius (Mims), who played bass, has a fancy, super 5-string that he uses and I was trying to dumb him down on this album. That’s why I had him play a really noisy P bass. I was using the James Jamerson setup on a lot of songs, where I was doing the round strings and we were using the foam. That setup was like the star on this record. It really had the warm, fat bottom.

Cheap guitars yield rich music for Fantastic Negrito, who telegraphs sharp-edged roots-based stories from his Oakland home base. Photo by Deandre Forks

What amps do you like?

The Fender Bassman. I had this other vintage one that I regret selling. It was a 1960s one. I’m terrible with names.

A Deluxe Reverb or Twin Reverb?

Twin Reverb! Twin Reverb.

That’s a classic.

I know, but I thought I quit. I have some copies of that one, too. There’s another one, Cave Valley amps. I love those fuckin’ amps. I recorded a lot of the record on that. It’s a small amp and he used kind of like Leslie parts. It’s interesting, bro. There’s something about that amp.

You say you’re a recovering narcissist. John Mayer has said he’s a recovered ego addict. Who’s got a bigger ego, you or John Mayer?

That’s so funny you said that. He said he’s a recovering what?

Ego addict.

Did you know that me and him just had a talk?

No, I didn’t.

I just had lunch with him last week. I remember telling him that, because I didn’t know that he said that. He was like, “What? Fuckin’ shit, I’m one too.” And I’m like, “Okay,” and we had a big talk. Who’s got a bigger ego? Fuck. Let me think ... that’s a good one. I think me and John Mayer—whoo—we may be really neck and neck on that. I think I’m in full recovery though.

that pulls people in.”

He said he recovered, too.

He may be, he may be. I liked him a lot. Whose is bigger? John, let’s take it to the stage. We’re both damaged people and I think we both realize it, and you know, we’re working hard on it. That was funny, when I said that, he looked shocked. Like, “Holy shit, did this guy just say recovering narcissist?” I was like, “Yeah, that’s me.”

What do you think of the Kanye thing?

Oh no. [Laughs.] Kanye’s thing, just me personally, hey, I don’t want any beef with Kanye, but I’ll just say it: I think Kanye suffers more from “I want people to talk about me.” I think that he may be a genius at that. This is the second interview I did today. I did one with someone in Italy and they’re talking about it. Kanye is a lot like Trump. This is what they both do. I think they might have, what’s the word, nihilist views. Which is like, “I don’t really believe in anything. I just am fuckin’ out here saying anything.” A few years ago he snatches that award from someone [Editor’s note: Taylor Swift at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards] and said, “George Bush doesn’t like black people.” Whatever it takes to get us to talk about him.

But I firmly, firmly do not like political correctness. Like we’re so entrenched in ideology that it’s like one or the other. Look, I’m a gun owner but I think we have a gun problem, you know what I mean? I’m against political correctness, but goddamnit, can we say transgender, white, Jew, and black? Can we just be normal and be like, “Hey man, let’s have real conversations. Hey, I’m a black guy and I kind of feel this way as a black guy,” and I’m like, “cool.”

We’re trying to fill the gaps here, man. We’re trying to talk to each other. It’s okay. We don’t have to be offended by fuckin’ everything. Now, we don’t have to be disrespectful, but we don’t have to be offended, and we can really build bridges. I believe that music does that shit. I’m really happy with this album and I’m ready to go tour, and go ruffle some feathers, because artists should do that. [Laughs.] We should make people a little uncomfortable.

Fantastic Negrito beat out nearly 7,000 entries to win the NPR Music Tiny Desk Contest in 2015—with a video he shot in a freight elevator. Here, he reprises his winning song, “Lost in a Crowd,” in a Tiny Desk Concert shortly after his victory.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)