What magicians really practice is subterfuge. The noisy blues mage Hound Dog Taylor was a master. His quote, "When I die, they'll say 'He couldn't play shit, but he sure made it sound good,'" is emblazoned on a T-shirt, over a photo of his 6-fingered fretting and sliding hand. And his stage persona—laughing and joking at warp speed and bullhorn volume, drunk, Pall Mall dangling from his lips, a huge slide raking his Kawai Kingston's strings in a way that made his amp detonate fragmentation bombs—was that of a barroom jester. But there is genuine magic at the nucleus of Hound Dog's wild-ass playing, for the effect it had on audiences and the story in sound it still tells.

"Anybody who heard Hound Dog live and says they didn't have a good time is lying," attests John Sinclair, the American counterculture hero who helped present Taylor while serving on the board of the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival in the early '70s. "He'd start his sets by yelling, 'Let's have some fun!' And everyone did. He's my all-time favorite artist."

The perpetually struggling musician from Natchez, Mississippi, could barely read words, but Hound Dog read his audiences like Shakespeare, using songs like "Wild About You Baby" and "Give Me Back My Wig," and his trio the HouseRockers' almighty groove, as helium for lifting hearts. He also knew how to find the soft spots in aching souls, with his tear-wringer "Sadie" or the nakedly abject "She's Gone."

"Anybody who heard Hound Dog live and says they didn't have a good time is lying."— John Sinclair

As a Black man raised in the depths of the Jim Crow Delta, then living and performing mostly in the hardscrabble urbanity of Chicago's South Side, Taylor knew the score and used his music to settle it. Although Hound Dog's been gone for 46 years, defiant joy still rings in the sound of the three singles and two studio albums he cut in his lifetime. And especially in live recordings, where he and his team, because they were more than a band, of co-guitarist Brewer Phillips and drummer Ted Harvey ran wild—as loud, carefree, and outrageous as they cared to be, not giving a damn about anything. Their brash, braying, and self-possessed music is the sound of freedom and, in the context of African-American history, even rebellion. And those who can't hear that through the raggedy tones and occasional hiccups are making the mistake of merely listening with their ears.

Young Dog’s Blues

Theodore Roosevelt Taylor was born in either 1915 or 1917 in Natchez, about 85 miles north of Baton Rouge, on the banks of the Mississippi. The small city's boomtown days were past. Its status as the lower river's nexus of steamboat traffic was erased by the expansion of railroads. But it continued to be a lively music town. In 1940, Natchez was the site of the infamous Rhythm Club fire, where 209 people lost their lives after being trapped inside the wood and steel building where Walter Barnes, a well-regarded contemporary of Duke Ellington, was leading his Royal Creolians orchestra.

By then, Taylor—whose first instrument was piano—was playing guitar and singing all over the Delta, when he wasn't driving a tractor on the farm where he worked. He had even appeared on Sonny Boy Williamson's popular King Biscuit Time live radio show on station KFFA in Helena, Arkansas. Two years later, Taylor hastily relocated to Chicago after the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of his home in retaliation for an affair he'd had with a white woman. For the first day, he crawled through drainage ditches and hid in fields as he made his way north.

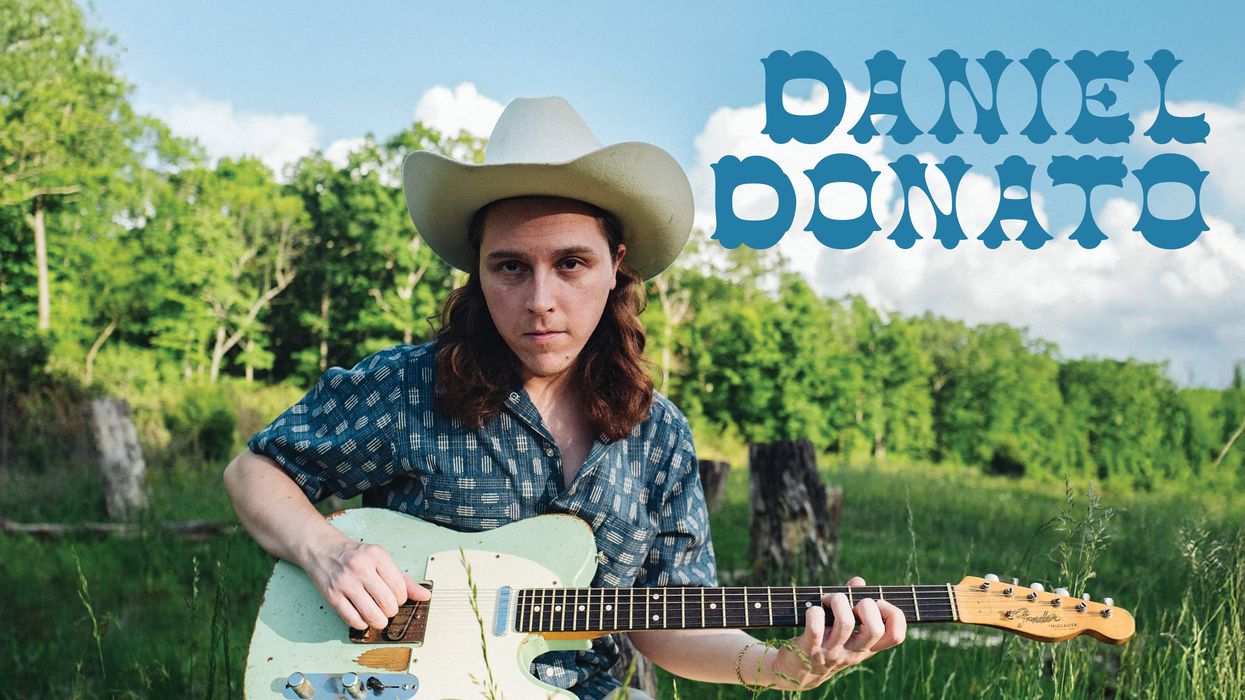

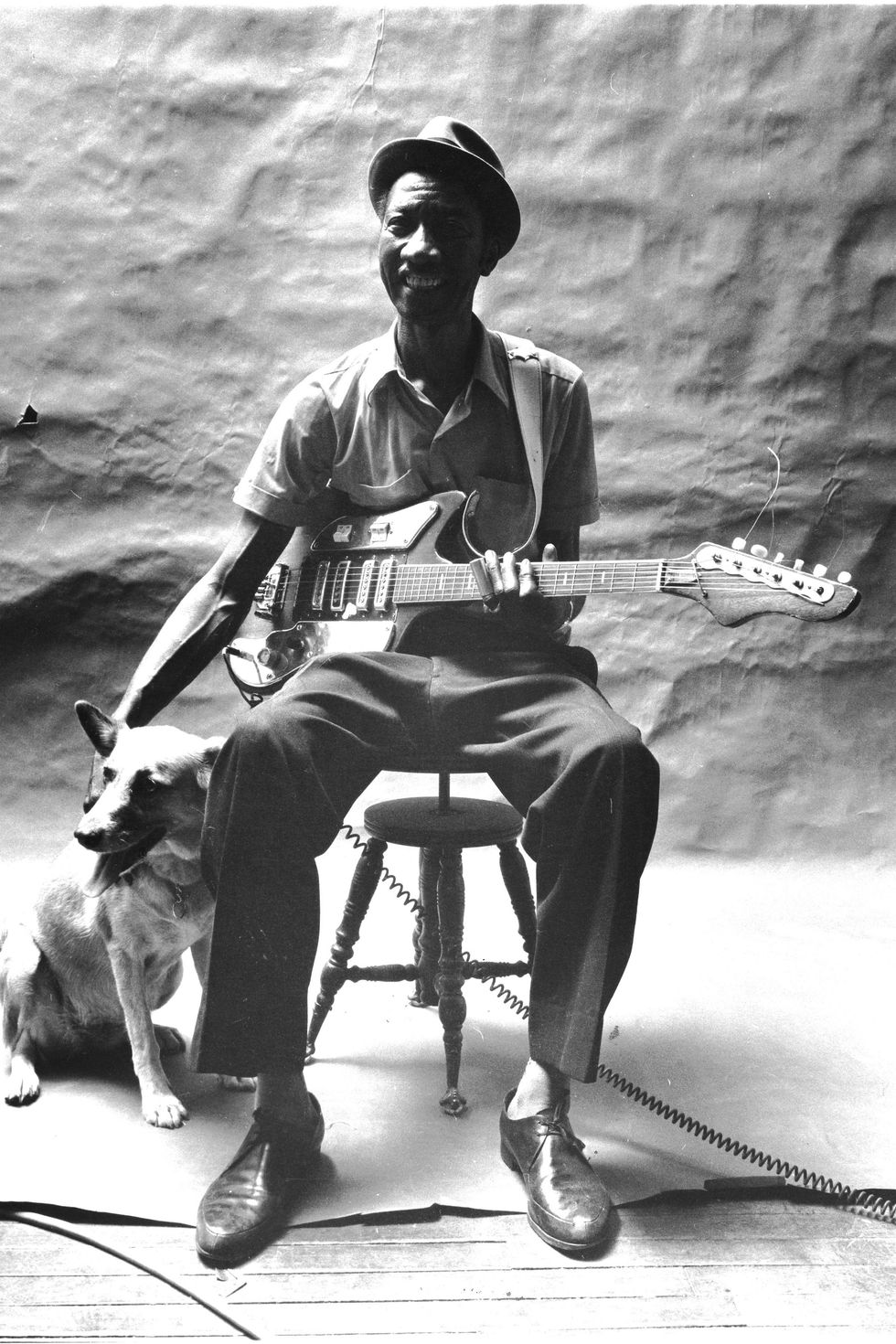

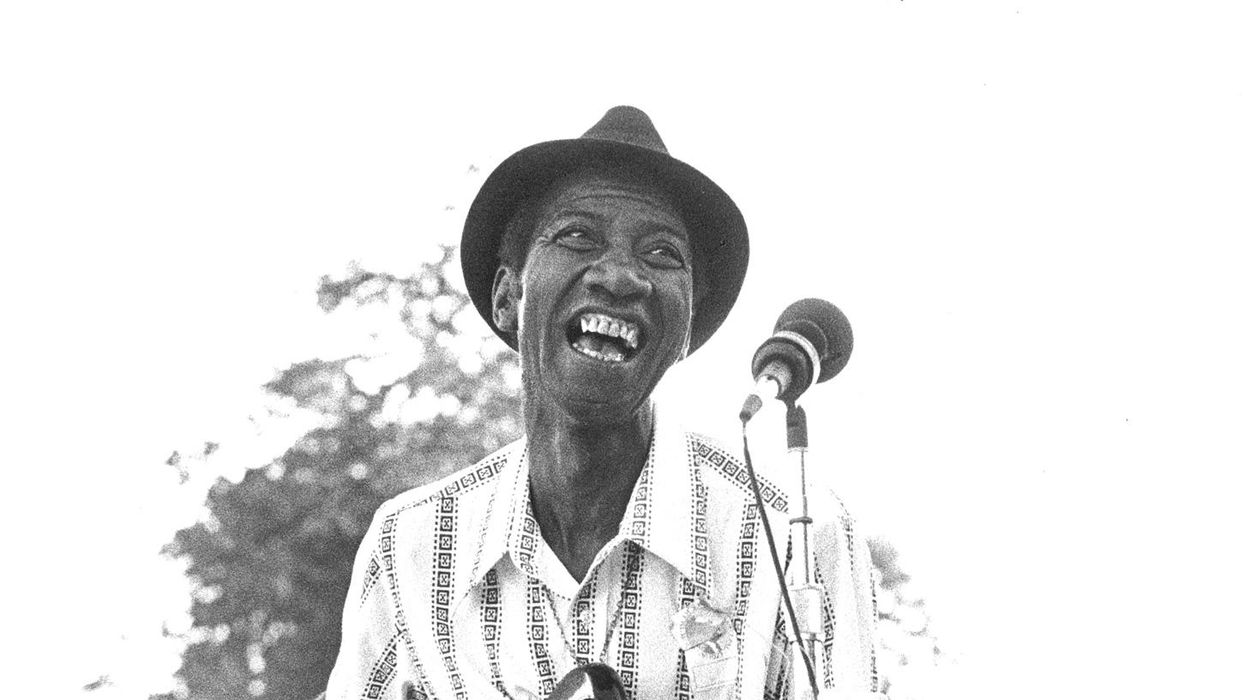

In this out-take from the photo session for his debut album, Taylor has his Kingston with a metallic pick- and body guard—and an amiable canine companion.

Taylor was born with polydactylism, a condition that causes the formation of additional fingers or toes. Both his hands had six fingers. Although the sixth wasn't functional, his fifth was extra-large, and some theorize that its additional bulk and strength may have helped him more aggressively pin the strings with his slide. At one point, as fable has it, he tired of being razzed for his difference and used either an axe or a straight razor to cut off the extra finger on his right hand. The resulting pain and blood led him to leave the left alone.

For his first 15 years in Chicago, Taylor played gigs but made a living via day jobs. Under the spell of Elmore James, whose early '50s singles established him as a star, the Dog began playing more and more slide, crafting his own raw distillation of James' keening, cutting, aggressive style and even copping his bawling vocal approach. In 1957, Taylor was building cabinets for televisions when he made the decision to chase the muse full time. Two years later, he met guitarist Brewer Phillips on a gig, and the HouseRockers began to gestate.

Through the '60s, Taylor eked out a living in Chicago's Black working-class bars, which stayed open long and late. At some point, he got the nickname Hound Dog, which, let's face it, is cooler than Teddy Roosevelt. Tales vary, but it was either bestowed upon him because of his tireless pursuit of members of the opposite sex, or because he actually did look like a canine, with his prominent ears, large nose, and rounded eyes. He reportedly developed a pre-show ritual of downing a shot of whiskey, a mixed drink, and a beer in quick sequence just before taking the stage, which he'd then command for a series of sets sometimes stretching to six hours or more. The typical fee was $30 for the band, bumped up to $45 on weekends.

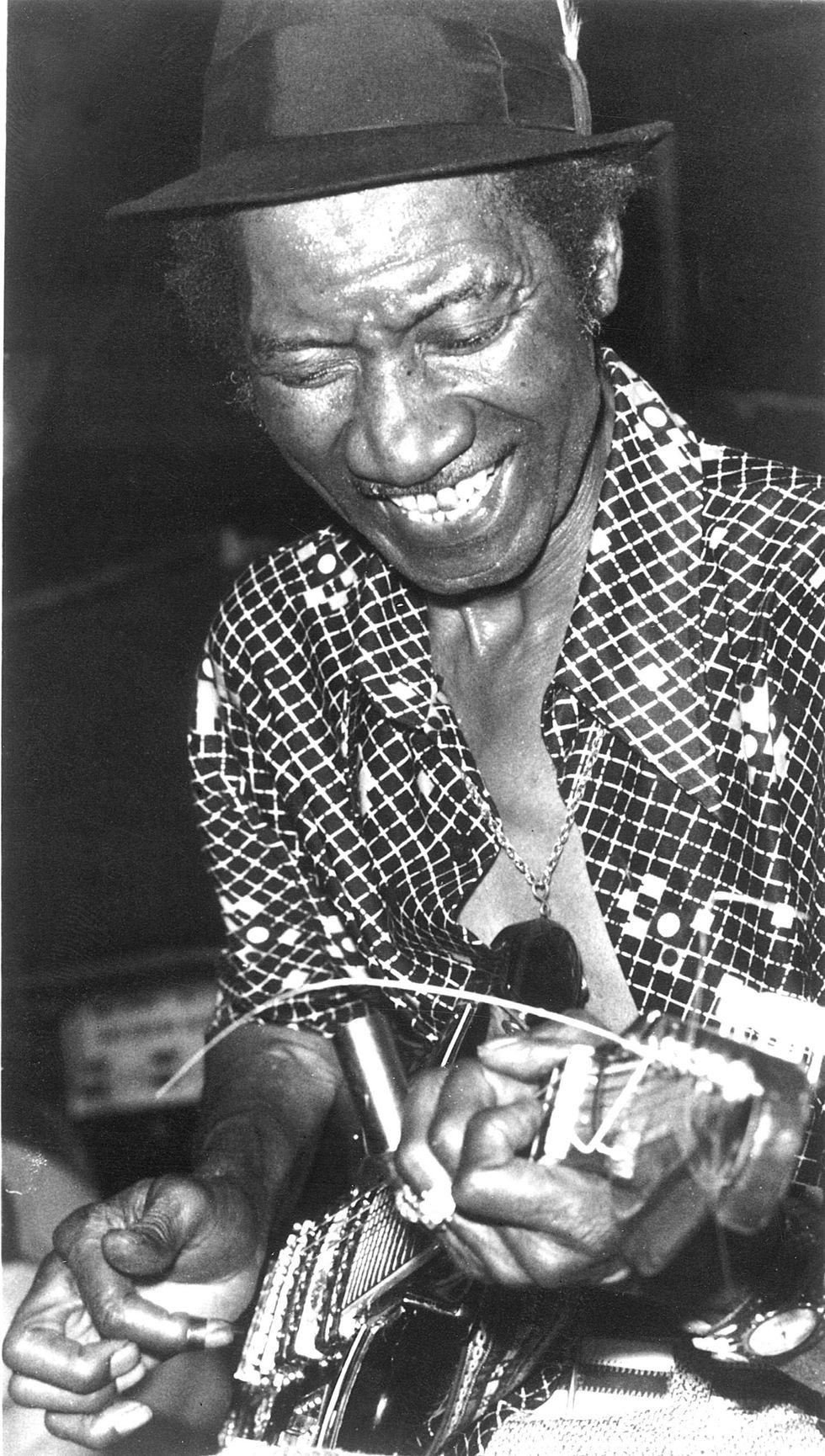

Hound Dog Taylor, natty as always, digs in hard for some single notes. See the steel pick on his right index finger? That's part of why his sound is often so explosively bright.

Photo by Jack Lardomita

In 1965, he and Phillips added drummer Ted Harvey, and their sound coalesced. With Harvey as their tireless sparkplug, they developed a loose but brilliant language by meshing their guitars. Mostly Hound Dog took the lead, with his slide and howling voice, while Phillips laid down a stone-finger-buster riff as a bassline. Often when you hear an instrumental by the HouseRockers, like "Phillips Screwdriver," that's Brewer at the fore, aggressively playing patterns or fiendishly mean 'n' dirty single-notes in a style gleaned from his early lessons with the great 6-string innovator Memphis Minnie. In truth, Phillips was a better player than Taylor, but Hound Dog had the schiznit, and—with his crew at his side—laid it down like Godzilla.

Enter the Gator

Three singles between 1960 and '67, including a release on the Chess subsidiary Checker, did nothing to enhance their fortunes. In '67, Taylor somehow obtained a slot on the American Folk Blues Festival tour of Europe, but he hated the experience, because his style didn't mesh with his fellow travelers, which included Little Walter, Koko Taylor, Son House, and Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. But in 1970, the coin flipped. Music-loving, recent college grad Bruce Iglauer had moved to Chicago for a job at Bob Koester's famed Jazz Record Mart and Delmark Records operation, and to chase the city's thriving blues. Taylor had told him about a regular Sunday gig he held down at Florence's Lounge, at 5443 Shields Avenue, on Chicago's South Side. It was a classic workingman's bar in a standalone building made of brick and cinder blocks, with a cubed-glass window and a dark, wood-paneled interior. As anyone who has pursued regional music styles to their depths knows, this is the kind of lair where wizards can sometimes be found. And on one afternoon in 1970, that's where Iglauer found Taylor, Phillips, and Harvey.

Iglauer recounts that afternoon, right down to the beads of sweat trickling down Taylor's cigarette-smoke-clouded face, in 2018's Bitten by the Blues: The Alligator Records Story, which he co-authored with Patrick A. Roberts. Talking about that gig 51 years later, revelation still rings in his voice. "It was the most fun I'd ever seen anyone have playing music," he attests. "I remember grinning all afternoon. They were so happy that it was like watching kids pretend to make music with brooms instead of guitars. Ted Harvey worked at a loading dock for Montgomery Ward, and Brewer Phillips worked construction. Hound Dog was the only one who made a halfway living playing music. So their only motivation for being there was to have fun."

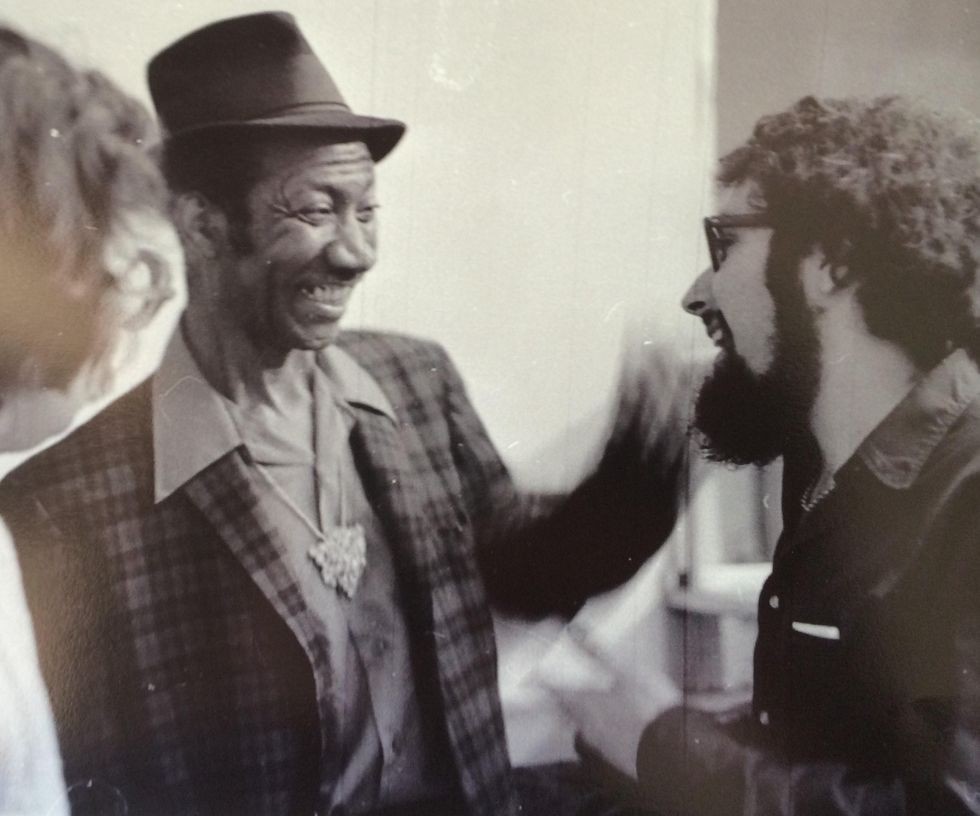

The meeting of Hound Dog Taylor and Bruce Iglauer was a turning point for both men. Taylor rose from Chicago's working-class bars to club, festival, and college stages around the world, and Iglauer became the proprietor of what would become the leading independent blues label, Alligator Records.

Photo by Nicole Fanelli

Beside colorful stories about his travels with the group—how Ted Harvey rarely drove because he'd end up motoring against traffic on the wrong side of a superhighway, Taylor sitting up all night in his hotel room with the lights on because he was frightened of having a repeated dream about being chased by wolves, Taylor's epic slide-guitar battle with J.B. Hutto, the trio's relief finding a Kentucky Fried Chicken in Australia after resigning themselves to starvation—the period also gave Iglauer an intimate view of what and how they played.

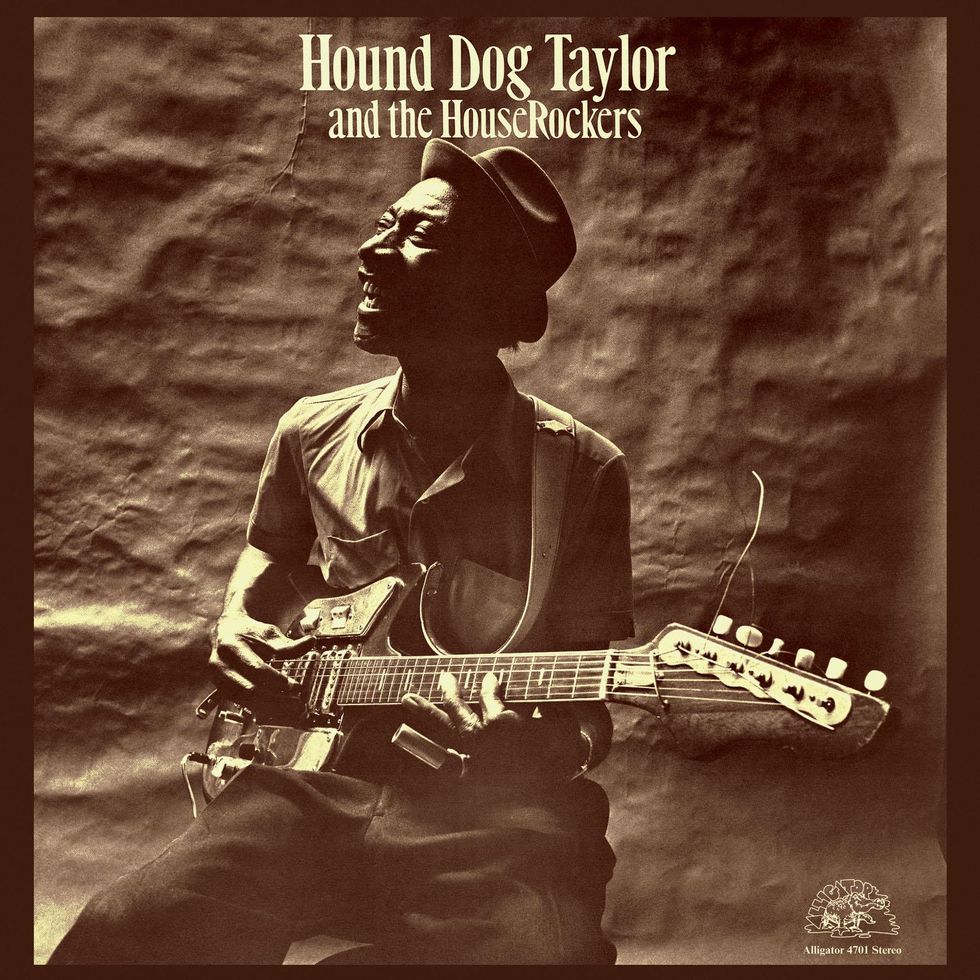

That day was transformative for both Iglauer and Taylor. After failing to get his boss to sign Taylor to Delmark, Iglauer used a $2,500 inheritance to pay for two days of studio time, then started Alligator Records to put out the results, Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers, in 1971. Natural Boogie followed in 1973. Today, Alligator is the world's largest independent blues label, celebrating its 50th anniversary and a storied history that includes hundreds of titles by Albert Collins, Johnny Winter, Son Seals, Lonnie Brooks, Lonnie Mack, Koko Taylor, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, and other legends. But for the next four years, Iglauer shepherded Taylor, Phillips, and Harvey in the studio and across the world's stages. He describes the trio's chemistry as "equal parts brotherly love, vicious adolescent rivalry, and Canadian Club."

How They Rocked

Taylor's main amp, the one heard on Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers, was a Silvertone 1400-series piggyback 6-speaker combo—a 60-watter he turned about as high as possible. That's the key to Taylor's gleeful distortion: funky gear and sheer volume. But Iglauer notes that he also witnessed Hound Dog play through a Peavey 1x15 and a Fender Super, and even, during a soundcheck at the Ann Arbor festival, into a Fender Twin with a Gibson Les Paul. "Hound Dog always sounded exactly the same."

The HouseRockers' chemistry was "equal parts brotherly love, vicious adolescent rivalry, and Canadian Club."—Bruce Iglauer

Taylor's guitars of choice were a pair of Kawai-made Kingston S4Ts, with fat necks, whammys he didn't tend to use, an on/off slider for each of four pickups, and master volume and tone controls. One had a Telecaster pickup subbed in, plus a metal pickguard and upper body protector, and both of these then-$50 pawnshop specials were difficult to keep in tune, but perfectly suited to Hound Dog's raw exhortations. Dan Auerbach owns one of these guitars and played it on the Black Keys' most recent album, Delta Kream. (For more on this guitar, see "Dan Auerbach Summons the Ghosts of Mississippi Blues" in the May 2021 issue.)

"Hound Dog did not dampen the strings like some slide players do, and essentially approached the instrument like Elmore James, but in an even more aggressive fashion," says Iglauer. Taylor also made his own slides. He'd slice metal tubing from a kitchen chair, long enough to extend across his guitar's neck, and then pound a piece of brass tubing into it, so it would fit his finger better and have more weight.

Listening to Taylor's first two albums, plus the posthumous live release Beware of the Dog! and the live-and-studio-leftovers Release the Hound, provides a strong vision of the trio's dynamic. Harvey is a surprisingly adept drummer and takes breaks where his rhythms veer in jazz-inflection directions. Taylor is heavy handed, tempering his ringing, grinding, often-turbo-speed slide with barking single notes to open up his verses, and chords that smash with sledgehammer audacity. The steel pick he wore on his right index digit adds to the shrillness of his tone—especially when he pecks out single notes like a brawny rooster. And Phillips plays far more than basslines on his guitar, even when fulfilling that role. His figures are packed with nimble variations, although he never shortchanges the pulse, and his solos offer a scalding challenge to copycats.

Taylor's debut album was produced and released by Bruce Iglauer, and established his Alligator Records imprint. The label is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year.

"Hound Dog's tuning was typically somewhere between open E and open D," Iglauer continues. "They tuned by ear, so it was relative." Especially after the night wore on and the whiskey bottle emptied. "Once, Hound Dog tried to quit drinking, but it was terrible. His hands couldn't stop shaking, and he couldn't play, so he started again."

The Other Side of the Dog

Like the animal whose name he wore, Hound Dog Taylor loved being with people. Fans around the world knew him as funny, warm, smiling—the perpetual genial host. "Even when he was at home, he was 'on,' just like he was onstage—the life of the party," says Iglauer. And whenever the young record man visited Taylor's apartment, it was buzzing with visiting friends and relatives. But in his quiet times, Taylor often appeared sad and regretful. "He seemed to feel that he missed out on a lot of things in life," says Iglauer. And he persecuted himself over what he saw as a lack of musical and practical education. "I don't believe he appreciated the depth of his own soulfulness or the transcendent joy that his music created."

Oddly, one of Taylor and Phillips' joys was argument. Once, they bickered all the way from Boston back home to Chicago, a 983-mile trip, about whether Hub City radio station WRKO was AM or FM. "One morning, after an all-night drive, Hound Dog woke up in the back seat of the car and noticed Ted Harvey was asleep in the front," recalls Iglauer. "He smacked Ted on the back of the head and yelled, 'Wake up and argue.' This was not always good or funny. In his book, Iglauer recounts finding Taylor and Phillips in a violent argument behind a club, knives drawn and out for blood. "I don't know what would've happened, because their tone made me feel like they really wanted to kill each other." Acting fast, he reminded both men they had a show contract to fulfill, and the battle stopped. "I think they were looking for an excuse to put their knives away," he says.

Hound Dog Taylor - 15 minute LIVE Ann Arbor 1973 Video

Here's Hound Dog Taylor onstage at the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival in 1973, with the HouseRockers, being his ebullient self. Listen for the pointed tone of his fingerpick on the single-note turnaround and the braying spray of tones that emerge from his ferocious slide. At times, it's really not that far from Sonic Youth, although it's always stone blues.

In May 1975, they went too far. During a visit to Taylor's home, Phillips made a tasteless joke about having sex with his wife, so Taylor shot Phillips in the arm and thigh with a .22 rifle. That ended the HouseRockers, and a few months later Taylor was in the hospital with inoperable cancer in his lungs and neck—his last stop before the great gig in the sky. Iglauer was a frequent visitor, and on his final stop-by, two days before the Dog slipped away, he was leaving as Phillips arrived to make amends with his friend. Taylor died on December 17, 1975.

"I don't believe he appreciated the depth of his own soulfulness or the transcendent joy that his music created."—Bruce Iglauer

Because of his half-century helming Alligator Records, Iglauer has known nearly every major electric blues artist, to varying degrees. When asked where Taylor fits in the pantheon, he pauses a moment, and then mentions George Thorogood, the band GA-20 … just a tablespoon full of direct torchbearers compared to the likes of Alberts King or Collins, or B.B and Buddy, or, of course, Stevie Ray Vaughan. "What Hound Dog did in terms of technique is not difficult," he says. "You can put your guitar in open tuning and find his notes. Hound Dog played simplified Elmore James, with slide chords and sliding and single notes on individual strings, but that groove …. his rhythm. Hound Dog was all about that groove."

That raw sound, that groove, and the pure joy of being alive that resonates in the music of Hound Dog Taylor makes me think of a quote from another great record man, Sam Phillips. The Sun label chief famously described the music of another musical canine, Howlin' Wolf, as coming from "a place where the soul of man never dies." Hound Dog Taylor's music also comes from that place.

Inside of a Dog—Approaching the Style of Hound Dog Taylor and Brewer Phillips

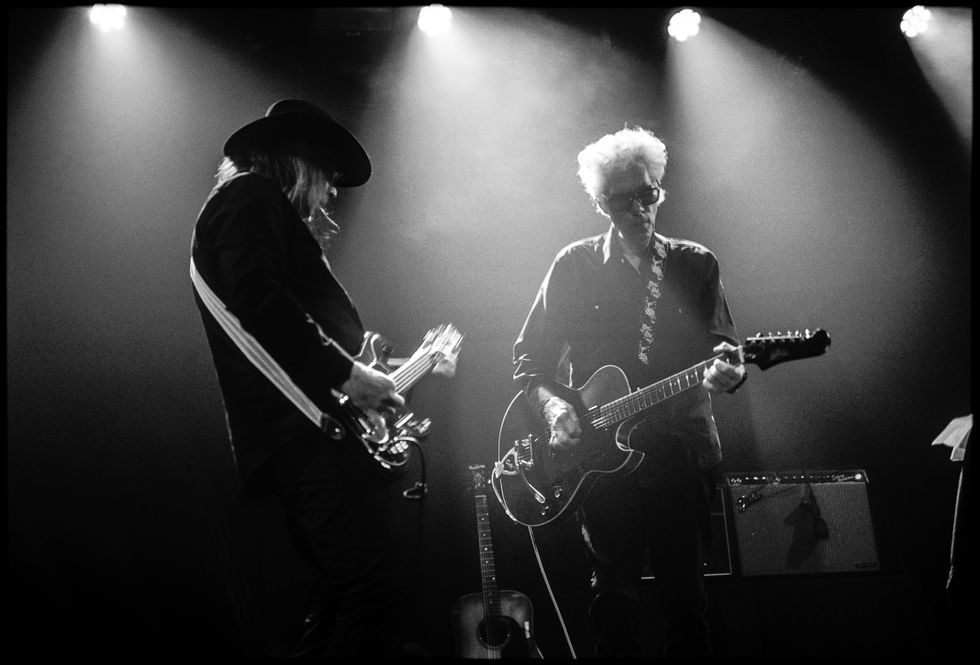

Pat Flaherty, left, and Matthew Stubbs took on the roles of Hound Dog Taylor and Brewer Phillips for their band GA-20's new album.

Dissecting the music of Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers is like conducting an alien autopsy. Things might sound and look kinda familiar, until you get deep inside, where offbeat stops and turnarounds, staggering shuffles, fast-flowing arteries of single notes, and fat-ass grooves abound.

GA-20 guitarists Matt Stubbs and Pat Faherty took their scalpels to the task to prepare for their new album, GA-20 Does Hound Dog Taylor: Try It … You Might Like It! "We've always loved Hound Dog's stuff, and real Chicago blues," explains Stubbs, whose main gig is with blues legend Charlie Musselwhite. And GA-20's two-guitars-and-drums lineup also makes the HouseRockers a natural frame of reference.

For their tribute album's 10 songs, Faherty played the role of Taylor and Stubbs chased Phillips' approach. Faherty found a Kawai-made relative of Hound Dog's Kingston, a Teisco, on eBay just before the sessions. "The sound is really in those pickups," he observes. "As far as intonation goes, you can't get the cheaper versions to go in tune past the second fret, and their strings couldn't even be lined up over the pickups correctly. So you have to get a better model, like Hound Dog had. I need a little tension when I pick, because the guitar is tuned to open C#, so I used .012s. Hound Dog would use that tuning, and his version of Elmore James's 'It Hurts Me Too' is almost in F." Faherty figures Taylor tuned mostly in the neighborhood of open D or Eb, and adds that E tuning is audible on the live recordings.

Faherty's initial experience playing slide was as a student at Berklee, under the guidance of jazz and textural guitar guru David Tronzo. "Hound Dog's style is super-loose, and the thing about his tone that makes him different from a lot of other slide players is that when he goes for it, he digs really hard. You can tell by the shrill attack that he's not smooth. The sound is very biting and in-your-face."

Stubbs offers that "Brewer was the secret weapon in the band. He solo'd like a madman. I've listened to Hound Dog my whole life, but had never gone through Brewer's style with a microscope before. Some of the turnarounds he used to play, like in 'Give Me Back My Wig'.… I remember thinking, 'Man, if I'm going to get close to this, I'm really going to have to double down.' He filled all the gaps with some really sophisticated playing. Brewer wasn't just following Hound Dog. He was constantly creating these little melodies on the side. And there are places where they dropped bars and changed rhythms, and you'd think they messed up, but then you listen to the live recordings and find out they made these changes together every time."

Stubbs favored a '51 Telecaster for the sessions at his home studio, and a reissue when he needed to tune down to C#. For amps, Faherty mostly used a Silvertone 1471, 5-watt, 1x8 combo. As for Stubbs' own main amp, it was their band's namesake: a 16-watt Gibson GA-20 combo.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)