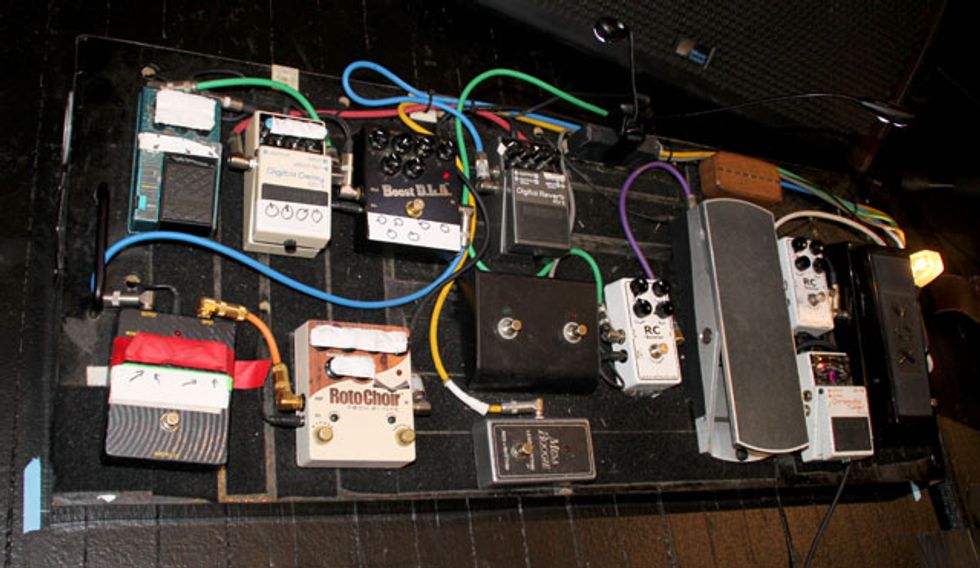

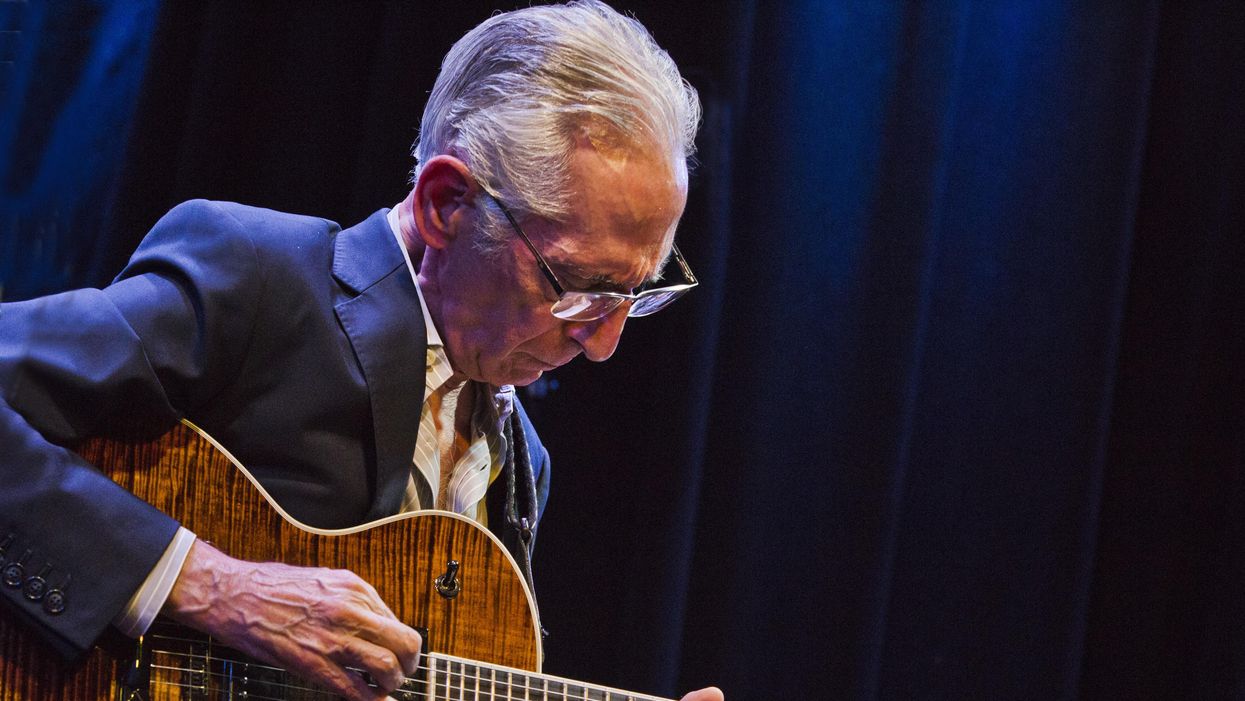

GALLERY: Steely Dan Touring Gear 2011

The guitars, amps, and effects used by Walter Becker and Jon Herington on Steely Dan''s 2011 tour.

By Jason Shadrick,

Jason Shadrick

Since attending a Dave Matthews Band concert as a teenager, Jason has been into all things guitar. An Iowa native, Jason has degrees in Music Business from Minnesota State-Mankato and Jazz Pedagogy from the University of Northern Iowa. Since then, he has spent time doing everything from promotion at an indie music label to organizing guitar workshops all over the country. Currently, Jason lives with his wife, son, and daughter in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.