“Does an instrument really contain or possess a part of the person’s soul who plays it?” ponders guitarist Bruce Forman. “Probably not … I don’t believe in that shit.”

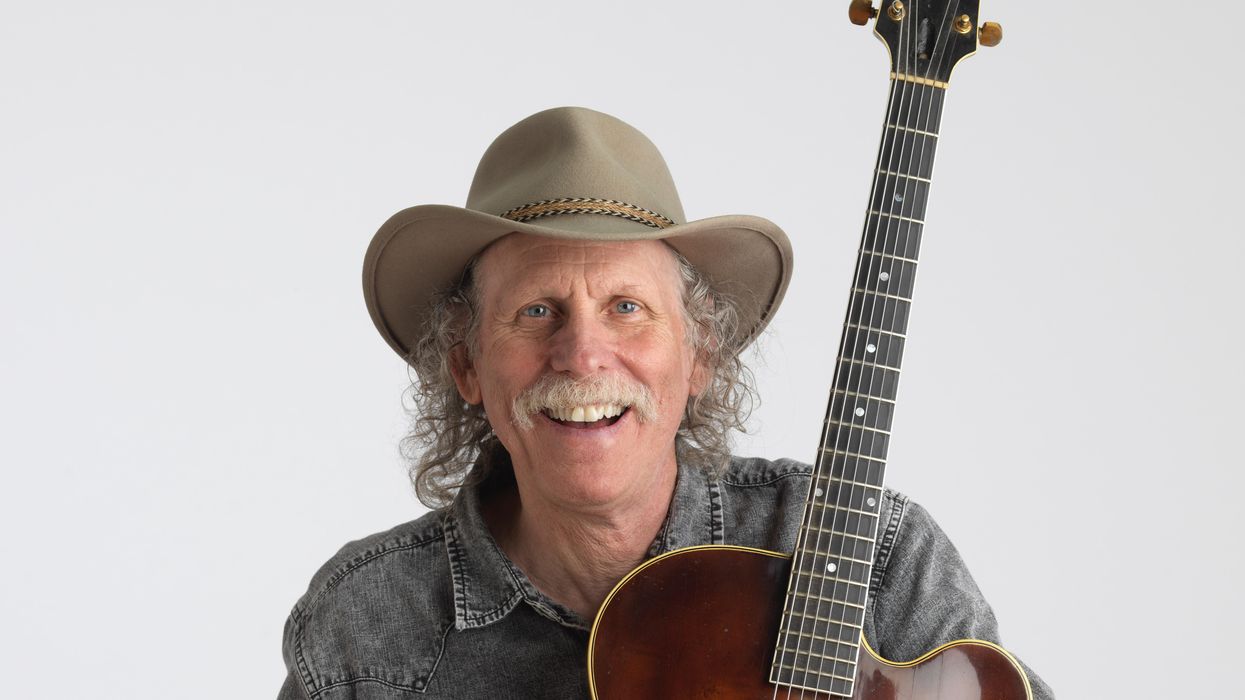

With his ever-present cowboy hat, and radiating a mustachioed grin, it’s hard not to get swept up in Forman’s skepticism-laced enthusiasm for the question. He’s been meditating on the idea since May 2020, when he purchased the Gibson ES-350 that belonged to his mentor, the one and only Barney Kessel. “The instruments can tell stories,” Forman preaches. “The instruments can tie generations together and they can bring people together. That’s basically what our soul is.”

If any guitar has a soul, Kessel’s guitar is it. Despite popular—and snazzily outfitted—signature models that were once offered by Gibson, Kay, and Airline, he stuck by his beloved ES-350, playing it almost exclusively on stage and in the studio. In one short YouTube video, “Barney Kessel talks about his guitar” (an excerpt from the DVD Barney Kessel: Rare Performances 1962-1991), he speaks briefly about what makes his ES-350 so special, pointing out the “high-quality” cobalt and copper in its 1939 Charlie Christian pickup, highlighting its bridge, which he says was made custom “along the principles of a fine violin bridge,” and praising the exceptionalism of the replacement knobs he took off a record player. Off camera, an interviewer asks Kessel how he feels when he plays this guitar, and he responds, “Pretty close to being in heaven.”

Kessel’s career was nothing short of legendary. In addition to his extensive and exemplary work at the forefront of the jazz world, where he advanced technical expectations and the vocabulary of the instrument, his membership in the Wrecking Crew found him recording countless pop hits and film soundtracks, making him one of the most recorded guitarists of all time. Given his close affection for his ES-350, it’s probably not overstated to say that the sound of this very guitar is embedded into our collective consciousness, which makes it a treasure.

But for Forman, the ES-350 is so much more than that. It’s a living artifact of his mentor.

“Barney was really funny. He had a great sense of humor, and so did Ray and Shelley. They could have been standup comedians.

Putting On the Gloves

Forman’s relationship with Kessel goes back to the mid-1970s. The Texas-born guitarist was a jazz-obsessed teen, which he says made him a bit of a “Mr. Magoo” once his family moved to San Francisco, where he was disinterested by the city’s thriving rock ’n’ roll culture. Rather, he attended jazz concerts and workshops frequently enough that Kessel began to take notice. Forman was eventually able to impress the older guitarist with his playing, and by 1978, Kessel hired the young devotee, who was just 21 or 22 years old.

“The first official gig where I was hired to play with him was in San Francisco,” he explains. “We played duo, then we both played solo, then there was a rhythm section, so we’d each play a trio tune. Then, he chose me to go on the road with him for a European tour of established master and upstart young guy—that was a big thing in the ’70s and ’80s.”

Kessel didn’t just choose Forman because he was a young talent that he wanted to support. He was looking for a sparring partner, and Forman had proven himself a worthy adversary. “When you play with him, it’s like a knife fight. He’s there to compete in a very cutthroat manner,” says Forman. “He wants to win, even though he appreciates you when you play great. He doesn’t want to make you play bad, but he wants to push it to the edge of his ability.” Forman insists he rose to the occasion and says, “It wasn’t easy for him, and I got him a couple of times. I knew what we were doing, and I was there for it. I think he liked that about me, as much as he might have hated me a couple of moments in the middle of it.”

TIDBIT: While Forman and company would have loved to work in the studio where the Poll Winners recorded their albums, the Contemporary Records building in Los Angeles no longer exists. Instead, they chose guitarist/producer Josh Smith’s Flat V Studio, in San Fernando Valley, and found photos of the original sessions in order to approximate miking techniques.

The two remained close as Forman’s career blossomed. Soon, he was playing alongside other jazz legends such as Dizzy Gillespie, Ray Brown, Oscar Peterson, Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Hutcherson, and Shelly Manne, simultaneously building an extensive discography, which includes releases on the Muse and Concord labels. He also became a committed educator through his work as a professor at University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music, where he’s become a mentor to countless students—most notably guitarist Molly Miller.

In 1992, Kessel—who was born in 1923—suffered a stroke that left him unable to play. Forman says that he would visit him and his wife, Phyllis, at their San Diego home and he would play the ES-350 for them. “Phyllis would bring it out. I don’t know if Barney really wanted me to play it for him,” he remembers. “He had a stroke and it was hard to read his emotions. She really wanted to hear it, and she wanted me to make sure it wasn’t falling apart sitting in the case.”

After Kessel passed in 2004, Forman continued to visit Phyllis and the ES-350. It was on one of these occasions that he had the notion to pay tribute to his mentor. “I had this idea that we should re-visit the Poll Winners with this guitar,” he explains.

“When you play with him, it’s like a knife fight. He’s there to compete in a very cutthroat manner.”

Then, There Were Three

In 1957, Kessel, bassist Ray Brown, and drummer Shelley Manne were at the top of their game and topping the jazz polls that appeared in the magazines DownBeat, Playboy, and Metronome. Confidently assuming the band name the Poll Winners, the trio recorded a series of five albums for Contemporary Records, the first four of which—The Poll Winners, Ride Again!, Poll Winners Three, and The Poll Winners Exploring the Scene—appeared between 1957 and ’60 and helped to usher in the popularization of guitar/bass/drums jazz-trio instrumentation.

“We have to realize those records were Earth shattering,” Forman enthuses. “Before that, there may have been some guitar/bass/drums bands, but not that I know of in the history of jazz. The guitar was in a band with multiple guitars, like Django or George Barnes, or it was in a vibes and bass kind of trio, like Red Norvo and Benny Goodman, or they were in with a piano, like Oscar Peterson or Nat Cole or Ahmad Jamal. The guitar/bass/drums … our instrument had not really grown to that level of responsibility and maturity in jazz.”

The heart of Forman’s concept for a tribute record was that the three Poll Winners’ instruments would be played by their protégés, all of whom were friends and collaborators. “John Clayton, who’s a Ray Brown protégé, has Ray’s bass. I knew that Monterey Jazz Festival had a set of Shelley’s drums, and I knew a guy in Portland who had a set of Shelley’s drums, and Jeff Hamilton, the reason he’s in L.A. is because Shelley brought him to take over [for him] in the L.A. Four. And I played in the trio with Ray and Jeff.”

Bruce Forman’s Gear

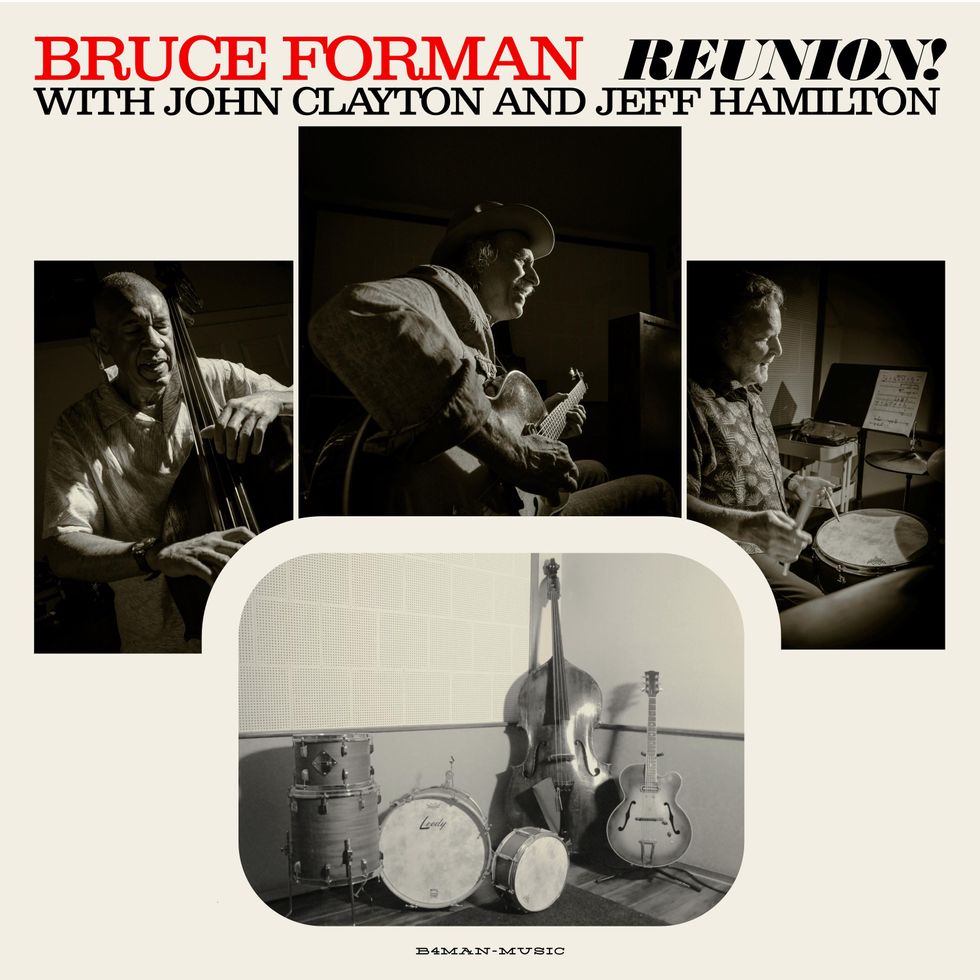

The trio that recorded Reunion!, from left to right: Bruce Forman and Kessel’s ES-350, drummer Jeff Hamilton, and bassist John Clayton.

Guitars

- 1946 Gibson ES-350 formerly belonging to and modified by Barney Kessel

Strings and Picks

- D’Addario Chromes flatwounds (.014–.018–.026w–.035–.045–.056)

- Dunlop Primetone 1.0 mm picks

Amps

- Gibson BR-3

- Henriksen Bud TEN

- Morgan JS12 Josh Smith Signature

But this tribute project would require a big favor from Phyllis Kessel, since Forman didn’t actually own his mentor’s guitar. “She said, ‘Boy, that’s great,’ but when she realized I had to take the guitar and play on it for a while, and probably get it set up, that was not cool. She wanted it totally in her possession.”

Eventually, Phyllis decided to sell the ES-350, and Forman suggested the auction house that handled the sale. “We both believed that it was extremely valuable. I didn’t want anything to do with it because I didn’t trust myself. Who knows how that could cloud my judgement in terms of getting the best thing for her,” he explains. But in 2018, the guitar sold for just a fraction of what either of them expected, purchased by “a guy from Oklahoma who loved Charlie Christian,” just like Kessel.

Forman and the buyer soon became email pals, sharing their affection for Kessel’s music. But between maintaining a regular gigging schedule and his teaching job at USC, Forman has a full plate, so he put the idea of the Poll Winners tribute to rest.

“We have to realize those records were Earth shattering.”

A Visit From a Ghost

Everything about this project changed in April 2021, when Forman swears he had a visitation from beyond: “I was playing at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center in Santa Cruz, and I’m driving up there and, I swear to God I’m not bullshitting, there was a moment when he [Kessel] was sitting there next to me. I couldn’t see him—this wasn’t a hallucination. I could just feel his presence. I could even smell his after-shave. He wore this kind of weird cologne shit. The whole drive up there, I’m thinking about Barney. I can’t shake it—didn’t even want to listen to music because I was too deep in all these memories. I get to the club, and I realize I played here with Barney about 35 years ago, but meanwhile I’ve played that club dozens and dozens of times, and I’d never once thought of Barney.

“I get inside of the club, and I still can’t shake Barney. He’s just there. So, I email the guy who had the guitar and said, ‘I’m having this heavy Barney Kessel flashback. I’m in this club we played years ago. Hope you’re getting along with the guitar. If you ever want to let it go, please let me get first crack.’ That’s all I said.

While Kessel’s ES-350 and Gibson BR-3 amplifier show plenty of signs of wear, they sound alive as ever on Reunion!

Photo by Patrick Tregenza

“Went up and played my set, came back, looked at my emails and I had gotten an email from him, and he said, ‘Bruce, it’s amazing you contacted me now. I just decided it’s probably best for me to sell the guitar. I don’t want to leave it for my wife or my kids. It’s too weird a thing to leave it to somebody else to have to deal with. The reason I bought it in the first place was to keep it from going into the hands of a collector who would take it out of circulation. So, I’d really love for someone like you who had a connection to Barney to have it. If you just give me what I paid for it, if you come and get it, and if you give me a guitar lesson, you could have it.’”

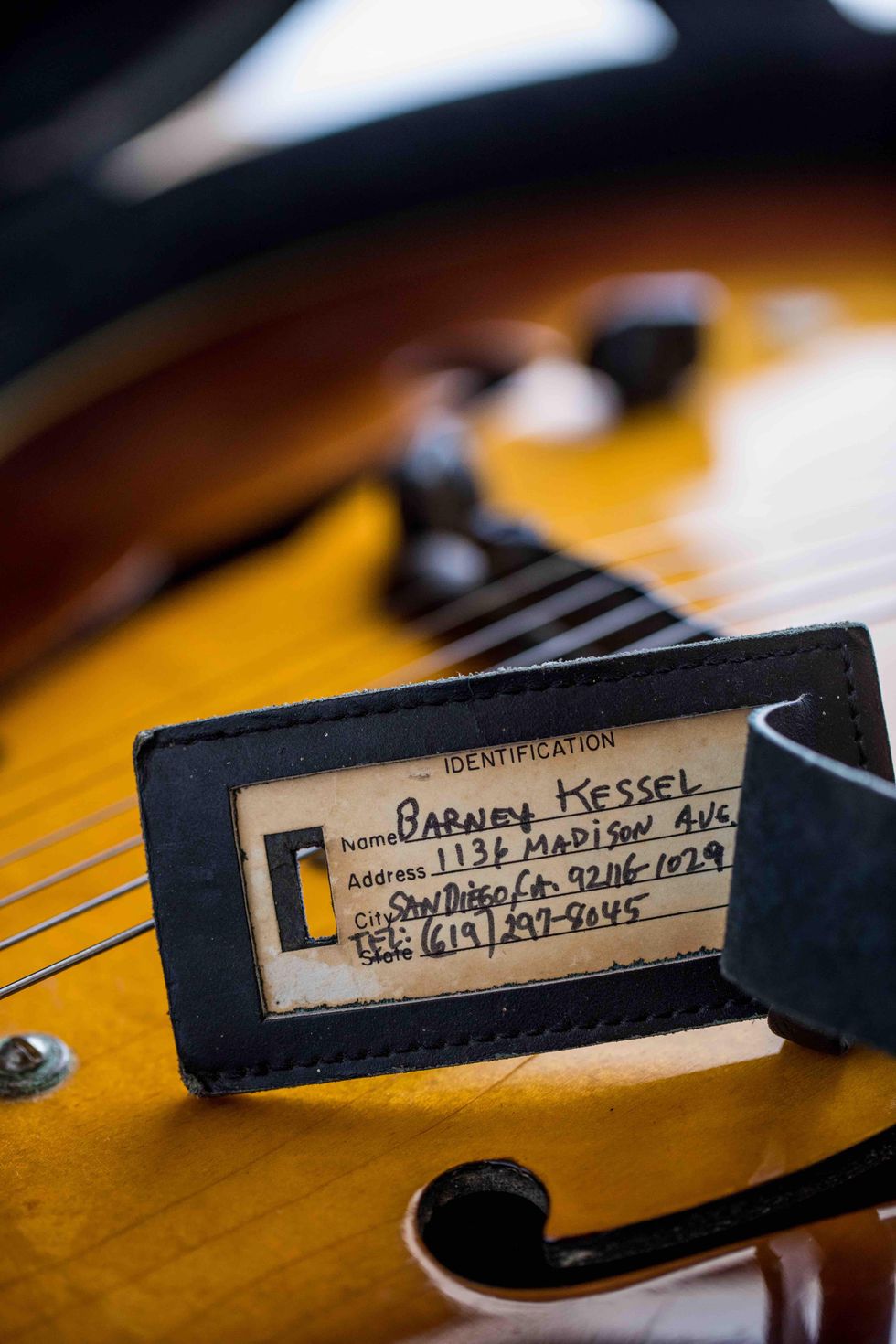

Two weeks later, Forman was headed to Colorado to pick up the guitar. When he returned home, Forman shot his own video with Barney’s guitar (which can be found in the Kickstarter page for the Reunion! project). As he goes over the details of the guitar, we get an up-close look at the finer details and see how it has changed over time. Kessel made extensive alterations to the instrument through the years, from replacing the fretboard and tuners, to painting the headstock black when he “went to war with Gibson.” The trapeze piece is rusty, as is the over-sized replacement jack plate that may be supporting the guitar’s significantly cracked sides. Hearing Forman play it, the ES-350 is alive as ever. It’s a bright and responsive instrument, and the always-smiling guitarist seems to approach every note and chord with pure joy. (There’s plenty of evidence on Forman’s Instagram, too, where he documents his “first chorus of the day.”)

“There was a moment when he [Kessel] was sitting there next to me. I couldn’t see him—this wasn’t a hallucination. I could just feel his presence.”]

The Reunion! Sessions

By the summer, Forman, John Clayton, and Jeff Hamilton headed into guitarist Josh Smith’s Flat V Studio with their respective mentor’s instruments. Forman even brought Kessel’s Gibson BR-3 amp, which a friend gave him as a gift (though he also used a Henriksen Bud TEN and a Morgan JS12). They wanted to pay tribute to, but not re-hash, the Poll Winners albums. “It’s a tribute but it’s not a tribute in the way most people do tributes. It’s really more like kids getting together playing their parents’ instruments,” says Forman.

Rather than taking the most obvious route and covering tunes on the original albums, the trio looked for a more personal way to evoke their mentors. Throughout his arrangement of Kurt Weill’s “This Is New,” Forman uses the intro figure that Kessel played on “Cry Me a River,” which he recorded with vocalist Julie London, as a recurring motif. Forman says that’s “probably the most famous thing he did.” His “Barney’s Tune” is an original based upon the jazz standard “Bernie’s Tune,” where he uses sliding harmonized thirds to recall Kessel’s style. The sole entry on Reunion! that also appeared on The Poll Winners is the jazz standard “On Green Dolphin Street.” But even on that track, Forman takes a different approach, injecting it with the feel of the once-omnipresent guitar showpiece “Malagueña.”

Kessel’s guitar’s case still wears this hand-written luggage tag from its former owner.

Photo by Patrick Tregenza

“Barney was really funny. He had a great sense of humor, and so did Ray and Shelley,” Forman says, and laughs. “They could have been stand-up comedians. And a lot of times in the music, they do silly, funny-ass shit [like that] that was just really cool.”

While the loose and playful feeling of the Poll Winners is always part of the music on Reunion!, Forman’s personality and musical voice plays the biggest role. He’s a fiery player whose deft, energetic chording propels the songs with swinging style, while his zesty melodic lines fly off the fretboard. Much like Kessel, he plays from the gut with a palpable sense of enthusiastic glee. And while Kessel is, obviously, a huge influence, Forman’s playing also reveals a love for his favorites, Charlie Parker and Count Basie. At this point in his long career, though, he mostly just sounds like himself. Hearing him play on Kessel’s gear, the tone of the ES-350 incorporates so well with his style and it just seems to make sense.

”As Forman tells it, that’s what Barney knew all those years ago: “On one of the first days of one of the first tours [with Kessel], he said, ‘Do you ever wonder why I picked you?’ And I said ‘yeah.’ I could name four or five guys I would have expected him to pick. He said, ‘I picked you because you play the way I play, but you don’t sound like me.’ Which is kind of cryptic, you know?” he laughs. “But I got it—he’s right.”

YouTube It!

Hear Barney Kessel’s guitar in Bruce Forman’s hands, live in the studio during the making of Reunion! The trio expertly navigates the tune “Feel the Barn” with dynamic, swinging interplay, led by Forman’s bright, clear tone and melody-first approach to improvisation and harmony.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)