The composer and co-creator of the Allman Brothers’ guitar legacy dies at 80, leaving behind 55 years of recording, performing, and legendary tales.

Magic happened when Dickey Betts and Duane Allman played together. Their sinuous, twined, harmonized guitar lines—inspired in part by Western swing and Miles Davis—were like nothing else in rock when the Allman Brothers Band’s debut album was released in 1969. And their Les Paul and SG partnership led the way in creating the Band’s reputation as the finest rock ensemble players of their day. Although that partnership was short-lived, due to Duane’s fatal motorcycle accident in 1971, that transcendent dual-guitar sound, best captured in the heroic performances on the live At Fillmore East double-album, continued throughout the band’s career and became a hallmark of Southern rock, largely thanks to Betts. And it will endure as one of the most recognizable dialects of electrified guitar-based music.

Betts soldiered on with the Allman Brothers Band until 2000, living in the shadow of Duane, whose early death cemented his legendary status. But Betts’ playing was equally commanding—the yin to Duane’s fat-toned, slide-driven yang. As a composer, he minted melodies and riffs that endure. “Jessica,” “Blue Sky,” “Ramblin’ Man,” and “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” are Betts’ work. As a player, he was unerringly melodic, with a Gibson and Marshall tone that blended clarity and heft with the tang of distortion. He played loud. Really loud. But that volume fueled his expressive dynamic touch and his supremely articulate 6-string language was always worth hearing.

“The band was so good we thought we’d never make it. It was so amazing I don’t even know how to put it into words—even now.”

Dickey Betts died on April 18, reportedly from cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He’d been sidelined since 2018, when he had a mild stroke which was followed by an accident at his home, which necessitated surgery to relieve swelling of the brain. He was 80 years old.

Like the Allman Brothers over the decades, Betts’ own career had its hills and valleys, but his musical character and abilities remained intact until recent years. When I spoke with him a decade ago at Nashville’s Hutton Hotel, the then-70-year-old observed, “I’m amazed that at my age I’m still effective. I have a formidable band together and I write new songs, although mainly we just do renditions of things like ‘Jessica’ and other hits.

Those are fun to play and people enjoy those songs. I’ve got a full catalog of instrumentals that I could play all night if I wanted to. A rock ’n’ roll career is supposed to last about as long as a professional football player’s—five years and you’re done. But I’m still out there swinging, filling theaters, and playing festivals.”

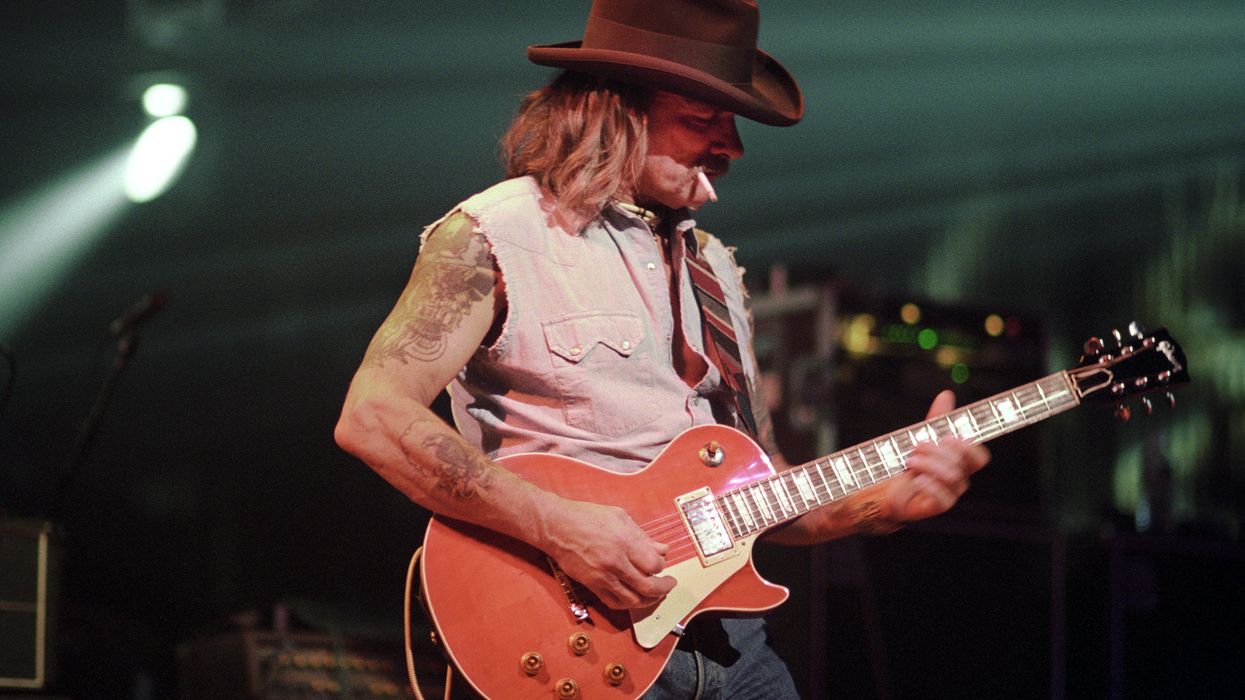

Passing the torch: Betts onstage with his son, Duane Betts, who leads his own band today. Here, they recreate the dual-guitar sound first cast in bronze by Betts and Duane Allman in 1969.

Photo by Jordi Vidal

Betts was in Music City on that occasion to celebrate the launch of the Gibson Custom Shop’s Southern Rock Tribute 1959 Les Paul, based on an instrument he owned, and was about to embark on one of his annual summer tours with his band Great Southern, which he’d been leading in various configurations since 1977. He also had his Dickey Betts Band, which he started in 1988 and included Warren Haynes, whom Betts drafted into the Allmans when the Brothers reformed in 1990 after a near-decade hiatus. I’d been warned by Betts’ handlers that he could be difficult, and Allman Brothers Band lore contains enough stories of his wicked temper and edge-of-violence outbursts to serve as warning. He was arrested for assaulting a police officer in 1993, and reportedly held a knife behind his back during a band argument shortly before he was dismissed from the Allmans. But, sipping a glass of wine while wearing a sleeveless white tee shirt, a straw cowboy hat, and a necklace of alligator’s teeth, he was cordial, funny, and thoughtful.

He reflected on his role in bringing jazz influences to the early Allman Brothers, which tapered well with Duane and Gregg Allman’s blues sensibilities. “I got that, initially, from Western swing,” he recalled. “My dad did play fiddle, but we didn’t call it bluegrass. It was called string music and he also played Irish reels and things. So, I think I got my sense of melody from Western swing and my dad.

“I also got my sense of tone from my dad. I saw how my dad would pay attention to his fiddle sound. He knew how to tune a fiddle by putting a tone post in, to push the top of the fiddle up. He would move that post around until he had just the right tone. So, I think that search for tone is just in my disposition. I always wanted my guitar to have a little edge on it, but with a clear sound. I experimented with different speaker combinations until I found it. Part of your tone is in your hand, too.”

After playing in a series of bands from his native Florida into the Midwest, including an outfit called the Jokers that Rick Derringer name-checked in his hit “Rock and Roll, Hoochie Koo,” Betts was recruited for the Allmans by Duane in 1969. “We didn’t do it consciously,” Betts said of their conflagrant dual-guitar sound. “We knew that when we started improvising, things fit, and we didn’t analyze it. Duane was more real militaristic into urban blues. And then I had a Western swing lilt to my rock playing, and it fit together beautifully. A lot of older folks said they thought we sounded like Benny Goodman, and it made sense to me later on when I listened to Goodman. He was pretty hip for his day, and would interweave his instruments together, too. We also listened to Miles Davis, who we thought was one of the greatest composers and bandleaders.

“Right from the beginning, we knew what we had,” Betts continued. “The band was so good we thought we’d never make it. It was so amazing I don’t even know how to put it into words—even now. With Duane, Berry Oakley, Greg and me as the songwriters, with everybody’s musicianship … it developed like a Polaroid picture. Nobody knew what it was going to be. They tried it at first as a trio, with Duane, Berry [Oakley, bass] and Jaimoe [Johnson, drums], and they cut some demos that were okay but they knew it wasn’t the Cream or Jimi Hendrix. And Berry told Duane the magic was happening when Betts was around, jamming, and from there we just grew into a six-piece naturally.

“We were elated with our sound, but every record company in the country turned us down. ‘All the songs sound the same.’ ‘They don’t have a frontman’… all this corny junk. So, we just started to travel around the country playing for free. In Boston, I remember we moved into a condemned building and ran an extension cord from the next building. We played in the park there. We’d get some hippies together and build a stage.”

While ’69’s The Allman Brothers Band sold poorly at first, it received critical acclaim, and the band’s grassroots mentality and love for playing—often relayed live via extended versions of their songs with plenty of improvisation—took hold in the potent American youth culture. The follow-up, Idlewild South, fared a bit better commercially, but At Fillmore East became their breakthrough. Sadly, Duane died just three months after its release.

“When we started getting killed off, well, there was nothing we could do about that,” Betts reflected. “It was tough times after we lost Duane and then we lost Berry. But then we had our biggest record [Eat a Peach, from 1972]. We figured. ‘Why quit when you’re losing?,’ and it worked out.

“And then, of course, the whole thing came apart,” Betts said of his 2000 ouster from the band. He was removed by the other charter members for the transgressions he was notorious for: drug and alcohol abuse, aggressive behavior. “But the Allman Brothers weren’t like the Rolling Stones, where we toured every five years. We were a working band. Thirty years is a long haul—especially when you’re doing something where your emotions are on your shirtsleeve all the time. The social dynamics just blew apart.”

Regarding the Southern rock mantle, Betts said, “We didn’t like it at first. It was kind of a reckless business label put on us by record companies. We thought of ourselves as progressive rock. We wanted to be more sophisticated than Southern rock sounds. We also didn’t think Southern bands sound that much alike, so why categorize them that way? As I get older I understand it was about record company marketing, but the difference between Marshall Tucker and the Allman Brothers Band is vast. They were more Western and we had a lot more jazz and blues, and improvising. My favorite was Molly Hatchet.”

Until his stroke and other illnesses waylaid him, Betts settled into his own music, seemingly content to be out of the heavy cycle of touring and recording required by a major band, settled into his life on Florida’s Gulf Coast. “I like fishing,” he said. “We live on the water and I’ve got a boat. I’m an archer. I can shoot stuff out of the air. We hunt wild hogs on the islands. It’s good to have something to do when you go home besides take dope [laughs]. I’d always get in trouble. On the road you’re busy; you go home and you don’t know what to do. Now I have some other good ways to apply myself.” Betts is survived by his wife, Donna, and four children: Kimberly, Christy, Jessica, and Duane, a skillful guitarist and bandleader in his own right.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)