Musicians feel and experience influence in many ways. And to be certain, Tom Verlaine’s guitar playing—his deconstructed melodies, pointed attack, and capacity for flight—inspired many to attempt imitation. But for a lot of us, Verlaine’s guitar and voice, and the music he created with Television and as a solo artist, were much more than another set of musical tricks to nick. They symbolized liberation and freedom from musical constraints, the rush, promise, and exhilaration of bohemian city life, the world of poets, and the notion that outsider musical voices could find audience and reverence. In the end, Verlaine’s playing may have been impossible to duplicate. But the electricity in his expression suggested an enormity of potential to those looking for a ray of light in weird times.

Tom Verlaine was born as Thomas Miller in Denville, New Jersey, in 1949 and grew up in Wilmington, Delaware. (He later changed his last name to honor the French Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine.) As a youth he was captivated by Stan Getz, John Coltrane, and Richard Wagner. He took piano lessons, was drawn to the saxophone, and, in his telling, found rock ’n’ roll comparatively unexciting—at least until he heard the Stones, Yardbirds, Kinks, and Byrds. In their works he found the same sort of intensity he had found appealing in jazz. The revelation led Verlaine to guitar. And ultimately, the fusion of those influences—British Invasion energy, free jazz fire, and classical melodic instincts and concepts—would shape his approach to the instrument.

Verlaine conjured a visceral, even mystical sense of tension and release from his fingers. His lines could sound tattered and violent or hushed and tender. And in inhabiting the two worlds, he often approached the sublime elevation of his hero John Coltrane.

Verlaine moved to New York City in 1968. In time, he reconnected with fellow prep school delinquent and poet Richard Hell, with whom he formed Television in 1974. By then, Verlaine had also joined forces with another wildly talented guitar foil, Richard Lloyd. In 1975, Hell, whose bass chops and extroversion were better suited for punk’s more brutish side, was fired and replaced with Blondie bassist Fred Smith. Along with drummer Billy Ficca, they formed a potent rhythm section uncannily suited to Verlaine’s musical vision.

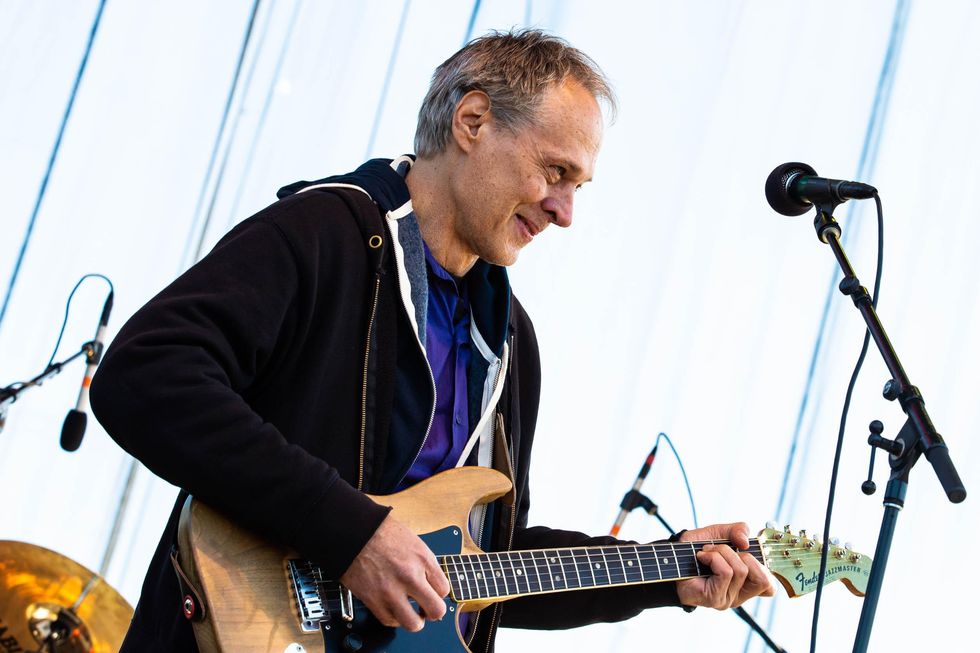

In this performance at Chicago’s Riot Fest in 2014, Tom Verlaine plays his Frankenstein S-style with a super-strat body, Danelectro lipstick pickups, and a mid-’60s Jazzmaster neck.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Even with the benefit of hindsight, it’s still a wonder that Verlaine and Television managed to make their 1977 masterpiece Marquee Moon amid the ossified record industry environs of the mid ’70s. Though Television was instrumental in jump starting New York City’s punk revolution (Verlaine talked CBGB owner Hilly Kristal into taking a chance on the band, effectively launching punk’s most celebrated venue), Television was an odd fit in a scene of misfits. Between Blondie’s high-energy pop moves, the Ramones’ bonehead-genius riff machine, and Patti Smith’s live-wire, larger-than-life poet-goddess presence, Television’s combination of wiry, twitchy garage-rock threads and searching, extended jams must have seemed alien at times. Had punk’s ethos of “shorter, faster, louder” been more strictly codified at the time, they might have even been cast out for letting their jams sprawl in the fashion of the Grateful Dead or Quicksilver Messenger Service (Verlaine’s quivering string vibrato often bore a more-than-passing likeness to that of Quicksilver lead guitarist John Cipollina).

Television’s modest first single, 1975’s “Little Johnny Jewel,” recorded for NYC scenester Terry Ork’s small label, offers a taste of how odd they must have sounded in contrast to their peers and the slick-and-super-mega chart toppers of the time. In some ways, “Little Johnny Jewel” sounds unbelievably small. Verlaine’s guitar, sent direct to the console, sounds thin, plinky, even miniscule. Yet Verlaine’s solo on “Little Johnny Jewel” is filled with deep yearning and ache. The bass riff, built on a few descending three-note figures, suggests back-alley mystery and creeping menace. It may sound small, odd, and misshapen next to the brutal linearity of the Ramones, but it perfectly captured the romance and sensuality of the city in which it was created, and the spirit of the art outcasts that inhabited its quieter, darker corners.

As Television found their footing and formalized their roles, they morphed from tentative and sloppy into a band capable of crooked clockwork precision and power. Verlaine and Lloyd, meanwhile, evolved into one of the most fascinating guitar duos ever. Lloyd leads were often marked by fluid exactitude. Verlaine, however, conjured a visceral, even mystical sense of tension and release from his fingers. His lines could sound tattered and violent or hushed and tender. And in inhabiting the two worlds, he often approached the sublime elevation of his hero John Coltrane.

Little Johnny Jewel

Television’s wave crested and crashed early on. Marquee Moon was a masterpiece on arrival. And its centerpiece, the song which shares the LP’s name, was anchored around an extended Verlaine solo that ascended from cool and spare to frantic and white hot. Live, the song was often explosively ecstatic. (If you want to know what musical freedom sounds like, check out the versions of “Marquee Moon” and “Little Johnny Jewel” from the official live bootleg, The Blow Up.) But Television’s highly evolutionary approach to guitar music did not sit easily alongside the more accessible fare of CBGB compatriots Blondie or the Ramones. Their second LP, Adventure, was less visionary than its predecessor, yet it’s a showcase for some of Verlaine’s most melodic and lovely tunes, as well as some of his choicest solos (“The Fire” for one). In theory, Adventure was a more accessible work than Marquee Moon, yet it floundered commercially, effectively ending the band’s first chapter.

In subsequent years, Verlaine, who had little interest in the more grotesque trappings of the rock business, remained quietly busy and prolific. His early solo LPs were rich with bright spots and great songs, but sometimes compromised by contemporary production or short on the extended incendiary guitar flurries that had become his trademark. However, 1992 marked a vernal, transformative year for Verlaine. It saw his reunion with Television, the release of the band’s underrated third, eponymous LP, and his own instrumental LP Warm and Cool. The latter, in particular, a collage of beautiful, drifting, and fractured mood pieces and lost spy movie themes, hinted at the directions Verlaine would often take in the future—filmic, intimate statements that reflected his love of cinema, Morton Feldman, and painting, as well as a winking sense of humor. That thread found realization again in 2006’s Around, another collection of enthralling instrumentals that found Verlaine at ease, and still capable of communicating palpable intensity and anxiety in a minor-key drift and a flurry of a few notes.

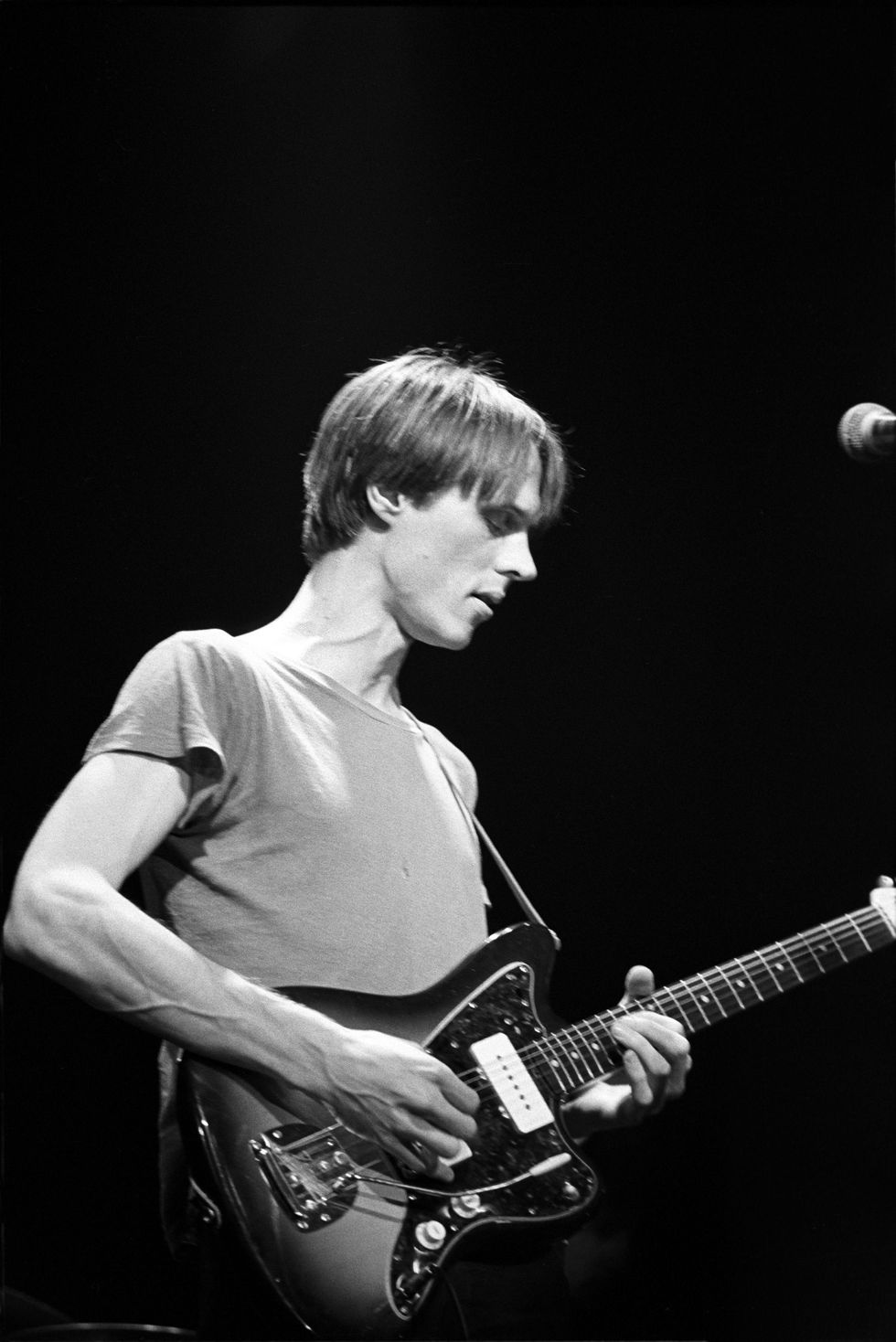

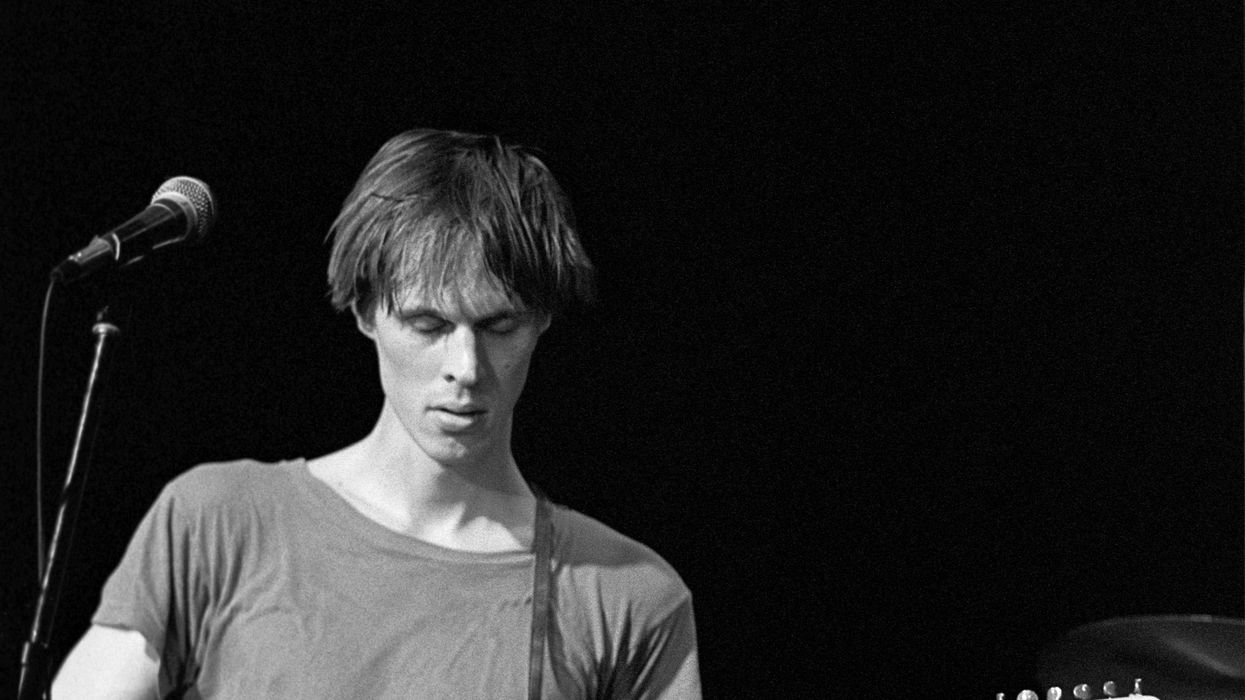

Tom Verlaine performs with Television at the Bottom Line in New York City on June 11, 1978.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

If you followed Verlaine in the press—and it would be fair to call him a bit press averse—it was easy to assume he was irascible and unapproachable. And when you felt his most intense musical moments penetrate your heart and gut like darts, it wasn’t too hard to imagine that a spirit of confrontation, even anger, inhabited them. Yet when my partner Meg and I opened for Television and met Verlaine, I found him kind, open, quiet, even shy. We drank wine, smoked cigarettes, talked about ’60s soul, painting, food, the stupid rents in our respective cities, and thoughts of getting away from it all. He asked that Erik Satie play before Television took the stage. And when he left to go to dinner, he left his guitar behind for me to play. He was a sweet guy, full of humility. In those moments we shared, it was very easy to understand where the tender melancholy in his songs and melodies came from. Verlaine possessed a blinding fire inside. But he was also impossibly cool, and positively overflowing with heart and soul.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.