Note from the editors:

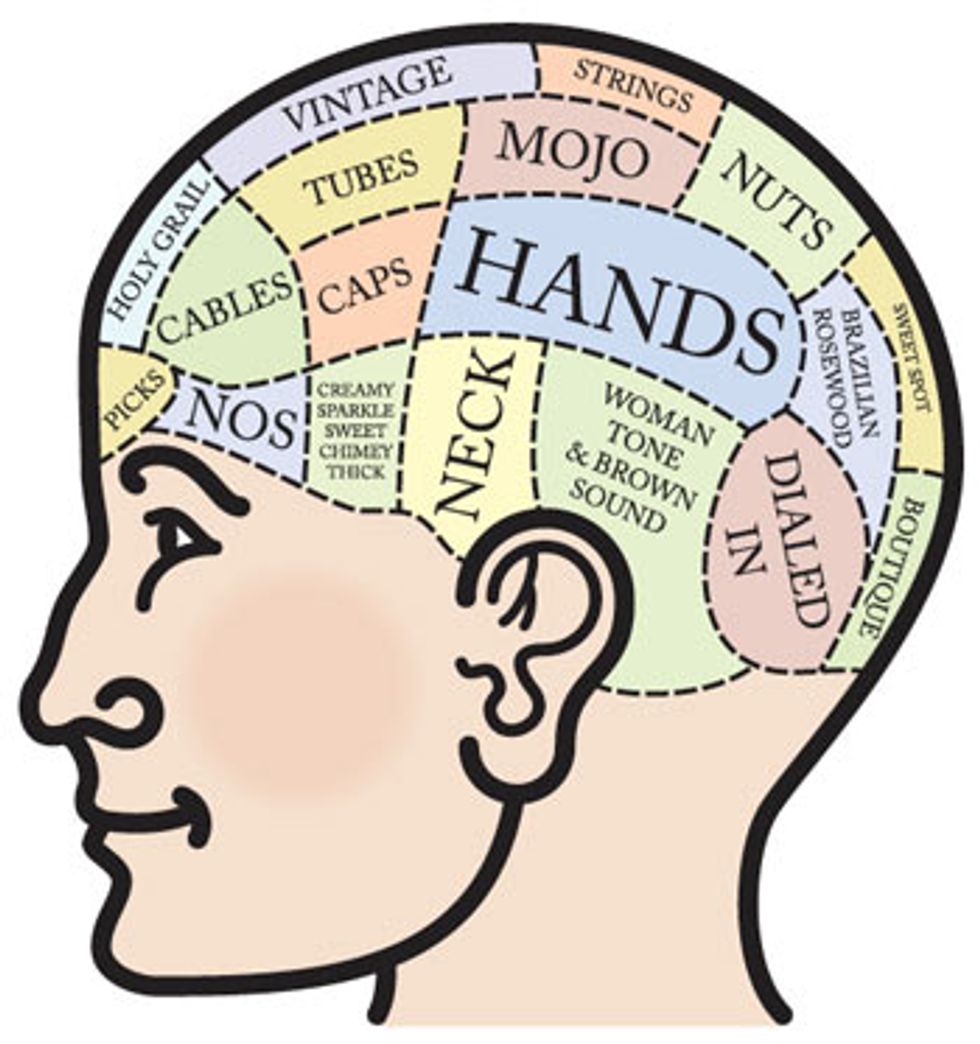

It is widely believed that a guitar’s tone involves fingers, physics, sometimes electronics, more physics, and then your ear. Not true. In reality, this signal path is not complete without one more thing… your brain. So why is it that the most complex part of the process, which is clearly the brain, is the one we never talk about? Assuming that beauty is ultimately in the brain of the beholder, why do so many beholders lust after the same handful of classic tones, when there are so many varieties out there? That can’t be a coincidence. Is that evidence that superior tones actually do exist, or is it simply proof that some mishmash of culture, acoustics, mojo— and who knows what else—have played with our heads without us even realizing it?

What exactly is happening when we try to produce certain tones with our favorite musical instrument? We believe it comes down to three things: psychology, science and religion (not that kind of religion; we’re talking about another kind of belief system). For the next three months, we’re going to explore these concepts. We know we aren’t likely to set the record forever straight; we’re merely trying to better understand the elements at play. In other words, our goal for this series is to mess with your head.

The first time I plugged a Gibson Heritage ’80 Series Les Paul directly into an unmolested 1985 JCM 800 sitting on top of a beefy 4x12 with Celestion G12H-100s I had truly set foot in tonal Valhalla. While full-bodied G chords and bowel-emptying detuned chugs rang in my ears, I just couldn’t wipe the sloppy grin off my mug. “That’s it!” I thought, finally putting down the axe as light continued to spill from the heavens. I had indeed heard the angels singing through those Celestions. My path toward the holy grail of tone had finally led me to a comfy cul de sac.

The first time I plugged a Gibson Heritage ’80 Series Les Paul directly into an unmolested 1985 JCM 800 sitting on top of a beefy 4x12 with Celestion G12H-100s I had truly set foot in tonal Valhalla. While full-bodied G chords and bowel-emptying detuned chugs rang in my ears, I just couldn’t wipe the sloppy grin off my mug. “That’s it!” I thought, finally putting down the axe as light continued to spill from the heavens. I had indeed heard the angels singing through those Celestions. My path toward the holy grail of tone had finally led me to a comfy cul de sac.

I’m sure most of you reading this are already yelling out the punch line from the cheap seats. Just keep in mind that was twenty three years ago, and much like the premise of the show Kung Fu, I am still, of course, a young grasshopper trying to snatch the tone pebble from the master’s hand.

After my short-lived tonal nirvana was over, I started searching for the next perfect tone. GAS set in hard, and I took up permanent residency in tonal purgatory, constantly trading, selling and buying guitars, amps, pedals, etc. in a concentrated effort to permanently grasp that slippery eel we call tone. Although that sloppy grin has a way of stretching across my grizzled grill every now and then, there’s always some other guitar slingers’ singing sound that will make my big toe curl up in my boot and send me reeling back to square one.

The Never-Ending Journey

If you’re anything like me, you experience occasional moments of clarity during your tone quest. That’s when you ponder questions like, “Do I really need 15 overdrive pedals and six Marshall 4x12 cabs?” Your answer: “Why yes. Yes, I do.”

Maybe you wonder why you sit through records made by a guitarist whose style you don’t really appreciate, but you’ll spin them anyway because his tone leaves yougob smacked. Perhaps you turn green with envy when you hear tales of people finding goldtops in attics, or Supro Thunderbolts and Maestro fuzz pedals at garage sales. Surely you wonder why you sneak expensive fuzz pedals past your better half as remorselessly as an unfaithful man scrubs lipstick off his collar. I don’t doubt that you also heat up the soldering iron with the mere thought of Dirk Wacker’s latest “Mod Garage” column, just like I do. You know exactly what I mean, and on some level, like me, you truly hope and pray that you never get well. I mean, really. Who wants to find their rig and be done?

Professional Help

I decided to get help—not necessarily to cure me of my GAS but rather to crack the code of it. I arranged a meeting with the manager of Mental Health Services at Concordia University in Montreal, Dr. Jeffrey B. Levitt, and decided to see if he could help me finally snatch that damn pebble out of that calloused ol’ hand.

Dr. Levitt isn’t your everyday quackery-spouting egghead. He’s actually one of us. About a baritone neck away from his framed psychology license in his office is a calendar boasting all of the solid lumber coming out of the Fender Custom Shop. On top of his desk, where other psychologists might have a Newton’s Cradle of clacking steel balls, he has a nickel-covered set of Throbak humbuckers. Dr. Levitt’s quest for tone has led him to a ‘92 Fender Custom Shop Telecaster that he plugs into a 65amps London head with a matching 2x12 cab, but his quest for tone remains as insatiable as mine.

“Very few people actually attain what they are desiring,” Dr. Levitt told me soon into our conversation. He went on, laying a clear foundation of thought from which we’d further poke and prod, “People will get a Gibson and a great amp and create a great sound but it’s never satisfying enough. To use an analogy, vanilla is great and is probably the best ice cream flavor but you when you see strawberry and chocolate and other flavors you have to dip in and attain it. The sonic vocabulary is so vast that once you get one type of tone it remains to be only one paragraph of one chapter of one story. I know people who are just crazy about fly-fishing and they will just obsess with water temperature, the type of fishing line, altitude, etc. and it’s no different from being a guitar enthusiast. Once you become passionate about something, the quest is never over. The quest, though, proves to be even more enriching than reaching the ultimate.”

I actually followed that. Bought it, too. From there, we both knew where this was going. I had more questions, and it was clear that with his background as both a tone junkie and a psychologist, I had the right person to ask.

Where’s the Rub?

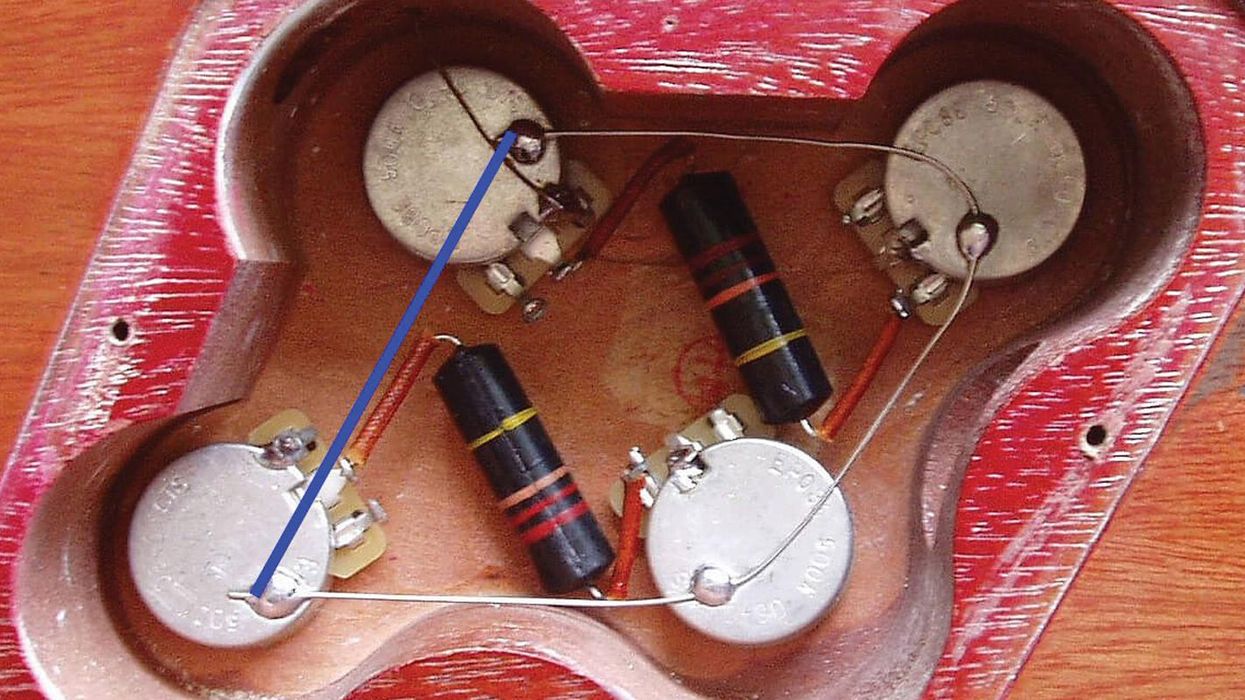

Usually, the seed of a guitar sound I want to attain is planted by a favorite record. The inspiration for the aforementioned Les Paul/Marshall revelation came directly from Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak record. As soon as I heard the midrangy crunch of the twin Les Paul and Marshall pairing on the title track, I was hooked and so it began. Quickly, my stock Gibson “Shaw” pickups seemed thin in comparison with Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson’s twin attack. I have now had every pickup combo imaginable in that guitar and have gotten the closest with a bone nut, TonePros aluminum tailpiece and bridge, RS Guitarworks pots and capacitor, and a WCR coils American Steele set of pickups. I truly love the sound of that setup, but you guessed it—I’m still not holding the Thin Lizzy cigar. I know I’m not alone in having a story like that.

“The more glorified an artist is, the more people will want to attain that fame, beauty and sound,” Dr. Levitt said. “We want to say that the tone is in the fingers but it’s very difficult to measure that and recreate that, so we go to other measures to attain cause and effect. Especially with signature series instruments, there is a fallacy that we will get this one-to-one correspondence with the person who inspires us.” I believe that on some level we all know what Dr. Levitt is referring to; we just don’t want to admit it.

“What does happen, though, is that these artists will provide a path,” Dr. Levitt suggested with a smile, “and as interests in other tones broaden, we will inevitably synthesize these tones and that’s where our own signature sound starts appearing.” My own signature sound? The longer I thought about that, the heavier that concept became.

Yes, Jazzmaster

Most of my amp, guitar and pedal choices are based on records I have become emotionally attached to. I want to recreate those emotions in my own playing. Television guitarist Tom Verlaine’s clean, angular and outside jazz guitar lines truly inspired me and had me researching his gear and finally hunting down and procuring a ’66 blackface Super Reverb and a pair of Jazzmasters (seafoam green’61 and a transitionyear tobacco ’65). Do I sound like Tom Verlaine? Not even close. Do I love the sound of my ’65 into the Super Reverb? Let’s just say I know that the hair on the back of your neck will stand at attention when I tear into “Marquee Moon.”

Oddly enough, before I was on a Verlaine trip my obsession with Jazzmasters came from guitarists like Sonic Youth’s Lee Renaldo and Thurston Moore and Dinosaur Jr.’s J Mascis. These mavericks were trying to remove themselves as much as possible from the classic Page, Clapton and Hendrix tones that a plethora of players were trying to shoulder up against. Another thing that I now see clearly is that my infatuation with classic Jazzmaster tones was a blessing for me as well as for other less financially endowed riffmeisters. The Jazzmaster’s doormat reputation had something to do with the slim price tag attached to its extra wide head stock. Heck, that could have been the same reason that threadbare rockers like Renaldo and Mascis’ gravitated towards them.

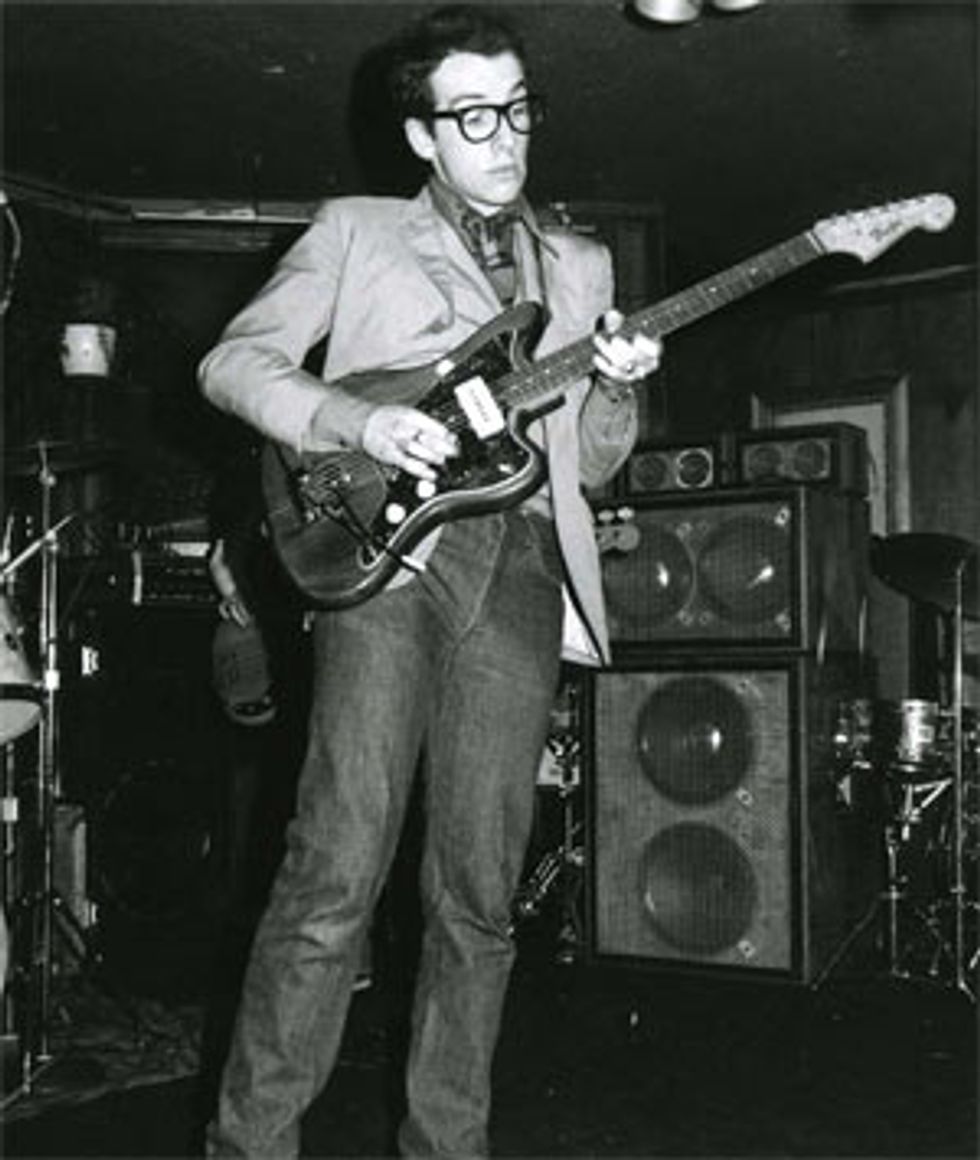

As you may know, when Fender introduced the Jazzmaster in ‘58 at a hefty price of $326 it was considered Fender’s top-of-the-line instrument. In a particurly skewed marketing attempt, Fender tried to snare the jazz guitar market with a poor choice of a name and a sound that had strong emphasis on pick attack and treble which was the polar opposite of the warm, Wes Montgomery-like tone that jazzbos were after. When the dotted-eighth players turned their noses up at Jazzmasters, surf bands were swift to pick them up, plug them into their reverb tanks and adopt them as their own. Once the Gretschs and Rickenbackers associated with Beatlemania took hold in the mid-sixties and the British blues movement would usher in the ‘burst Les Paul, the Jazzmaster was considered kindling at best. Those things were stacked to the rafters in the back rooms of most pawnshops. It wasn’t until fairly recently that Jazzmaster players like Elvis Costello, Mascis, Renaldo and Moore would receive signature guitars to help facilitate the demand for the model, and bump up the value of Jazzmasters on the vintage market. So what does the story of this red-headed stepchild of a Fender tell us about tone hunting and tone hunters? Simply put, there’s a lot that goes into the reputation of what might be considered “desirable prey.”

“Guitars like Steinbergers and Parker Fly guitars are amazing playing and sounding guitars but are hardly going to topple the sales of Telecasters, Les Pauls and Stratocasters, because they just don’t have the same aura,” Dr. Levitt surmised. “In the end, there will always be identification with what we glorify, and there will be iconic sounds and images in our collective conscious that we respect, value and seek. We want that connection to a story and if we peek behind the curtain and just see a washboard with a plank of wood stuck on, it loses a bit of the magic—and that’s what we’re after.”

Although many of us don’t want to admit it, Dr. Levitt’s theories do dredge up some truth. One has to look no further than the fetishists who are knocked to their knees when talking about the Peter Green/ Gary Moore ’burst, Roy Buchanan’s “Nancy”, Billy Gibbons’ “Pearly Gates,” Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “Number One,” Clapton’s “Blackie,” etc. Are those aficionados aware of how much they love the associated narratives behind those guitars, or is it truly the tones—and only the tones—that they’re after?

True Relics?

Truly famous guitars are famously dinged, and that helps differentiate them from other instruments while adding the realistic side of romance to the equation. True love survives wear and tear; it lasts. The problem is, most of us are incapable of working SRV “Number One”-level love into our guitars, emotionally and physically, but we want to participate in this “older is better” way of thinking. Accidentally or purposely putting a gank or two in your otherwise new Strat just isn’t the same—a weathered guitar has to look like it has been played by a pro for a long, long time. That’s why many companies offer a controversial relic’d version of their classic lines these days.

If you ever want to see two guitar fiends screaming bloody murder at each other, just bring up the topic of relic’ing. People get awfully testy when it comes to guitars bearing chemically treated and artistically abused armor. It makes sense that this is a sensitive issue—the fake beat-up look threatens the sanctity of an aesthetic that, until recently, was reserved for guitars that were authentically worn in and lovingly coaxed into producing todie- for tone over long periods of time. Those are rare guitars. Naturally, one side of the debate is very protective of that authenticity.

“We are programmed as humans to be drawn to stories and characters, and if there is no story we tend to find it less sexy,” Dr. Levitt confirmed. “For the most part, guitar players think ‘the older the better,’ and that’s partly because quality control was better at a lot of the major manufacturers in the fifties through the early seventies. Despite quality control lacking in the mid-seventies people will still pay vintage prices for these guitars, even though they may not be as well made as guitars are today. These beat up guitars tell stories, so when we see the relic’d look it triggers the mind to question how that happened and the mind begins to fantasize. When we pay for a relic’d guitar, we’re paying for a fantasy … unless you’re psychotic, you don’t actually believe that you’ve been on numerous tours with this brand new guitar, but you are now able to imagine that.”

There’s No Crying in Tone Hunting

Set aside the fact that certain eras had better manufacturer quality control and consider that there’s also an emotional connection with older music. It has endured the test of time and begat new generations of tone, therefore it rates higher on our tonal respect charts. Page’s “Black Dog” tone holds a certain nostalgic value compared to the guitar sounds anyone can crank out with digital tools these days.

“People seek comfort with the familiar, the tested, and with stability.” Dr. Levitt offered, displaying the kind of trained mental objectivity that unlettered tonehounds will struggle with. It’s much easier to simply swear that those old tones are downright “better.” No one wants to be told that their emotions are coloring their opinions about actual tonal “quality,” if there is such a thing.

“Perception is very tricky and relative,” Dr. Levitt continued. “A guitar could look like a piece of junk and be butt-ugly but may possess unbelievable tonal qualities due to the wood, construction, and other variables. But … I’d rather play a Tele, Strat, LP, or Rickenbacker, even if they’re sonically inferior, because I am enamored by their looks and history. That is, it makes me play better because I feel better about playing them. It’s a feeling that you’re a part of history, a part of a group, a part of a family—be it Fender, PRS, Gibson, etc. The “feeling” part and issues of connectivity and attachment… that’s all psychology.”

True Believers

I suspect you’ve called BS on some part of this article by now, and that’s fine. Surely there is such a thing as superior tone, psychology notwithstanding… right? Personally, I can’t say that I’m over my fixation with tone now that I’ve had a chance to chew on these pointy-headed concepts. I must say, though, I really do feel closer to whatever it is that I’m looking for. I haven’t reached that tonal destination yet, but looking back I know I’ve saddled up a bar stool next to it and shared a pitcher of draft with it.

If there is anything I’ve learned from our mutual unpeeling of the layers of the tone onion, it would be that the journey is far more enriching than the actual destination. Dr. Levitt suggests that much of this has to do with our natural inclination to seek out the explainable. In some way, our quest for Holy Grail tone is an enactment of our thought process. We want to reduce ambiguity. We try to frame everything within the parameters of cause and effect. We may not find the cause, but we get a good snootful of the roses every now and again, so we dutifully put our one foot in front of the other and continue down the winding path to eargasmic tone. It’s these prickly plants and their sweet aroma that make this whole trip worthwhile.

My eyes remain fixated on that perfect pebble. I’m still helplessly trying to grasp it away from the tone master, but in the back of my mind I also secretly hope to remain hamfisted and slow to grip. The day we are finally able to grab that elusive pebble could be a sign that our passion has truly run dry.

Next month—don’t miss part II, The Science of Tone, in which we ask the question: Isn’t our fixation with PAF and Nocaster tone kind of like a car buffs swearing that the Model T had the best-running engine ever made?

It is widely believed that a guitar’s tone involves fingers, physics, sometimes electronics, more physics, and then your ear. Not true. In reality, this signal path is not complete without one more thing… your brain. So why is it that the most complex part of the process, which is clearly the brain, is the one we never talk about? Assuming that beauty is ultimately in the brain of the beholder, why do so many beholders lust after the same handful of classic tones, when there are so many varieties out there? That can’t be a coincidence. Is that evidence that superior tones actually do exist, or is it simply proof that some mishmash of culture, acoustics, mojo— and who knows what else—have played with our heads without us even realizing it?

What exactly is happening when we try to produce certain tones with our favorite musical instrument? We believe it comes down to three things: psychology, science and religion (not that kind of religion; we’re talking about another kind of belief system). For the next three months, we’re going to explore these concepts. We know we aren’t likely to set the record forever straight; we’re merely trying to better understand the elements at play. In other words, our goal for this series is to mess with your head.

The first time I plugged a Gibson Heritage ’80 Series Les Paul directly into an unmolested 1985 JCM 800 sitting on top of a beefy 4x12 with Celestion G12H-100s I had truly set foot in tonal Valhalla. While full-bodied G chords and bowel-emptying detuned chugs rang in my ears, I just couldn’t wipe the sloppy grin off my mug. “That’s it!” I thought, finally putting down the axe as light continued to spill from the heavens. I had indeed heard the angels singing through those Celestions. My path toward the holy grail of tone had finally led me to a comfy cul de sac.

The first time I plugged a Gibson Heritage ’80 Series Les Paul directly into an unmolested 1985 JCM 800 sitting on top of a beefy 4x12 with Celestion G12H-100s I had truly set foot in tonal Valhalla. While full-bodied G chords and bowel-emptying detuned chugs rang in my ears, I just couldn’t wipe the sloppy grin off my mug. “That’s it!” I thought, finally putting down the axe as light continued to spill from the heavens. I had indeed heard the angels singing through those Celestions. My path toward the holy grail of tone had finally led me to a comfy cul de sac.I’m sure most of you reading this are already yelling out the punch line from the cheap seats. Just keep in mind that was twenty three years ago, and much like the premise of the show Kung Fu, I am still, of course, a young grasshopper trying to snatch the tone pebble from the master’s hand.

After my short-lived tonal nirvana was over, I started searching for the next perfect tone. GAS set in hard, and I took up permanent residency in tonal purgatory, constantly trading, selling and buying guitars, amps, pedals, etc. in a concentrated effort to permanently grasp that slippery eel we call tone. Although that sloppy grin has a way of stretching across my grizzled grill every now and then, there’s always some other guitar slingers’ singing sound that will make my big toe curl up in my boot and send me reeling back to square one.

The Never-Ending Journey

If you’re anything like me, you experience occasional moments of clarity during your tone quest. That’s when you ponder questions like, “Do I really need 15 overdrive pedals and six Marshall 4x12 cabs?” Your answer: “Why yes. Yes, I do.”

Maybe you wonder why you sit through records made by a guitarist whose style you don’t really appreciate, but you’ll spin them anyway because his tone leaves yougob smacked. Perhaps you turn green with envy when you hear tales of people finding goldtops in attics, or Supro Thunderbolts and Maestro fuzz pedals at garage sales. Surely you wonder why you sneak expensive fuzz pedals past your better half as remorselessly as an unfaithful man scrubs lipstick off his collar. I don’t doubt that you also heat up the soldering iron with the mere thought of Dirk Wacker’s latest “Mod Garage” column, just like I do. You know exactly what I mean, and on some level, like me, you truly hope and pray that you never get well. I mean, really. Who wants to find their rig and be done?

Professional Help

I decided to get help—not necessarily to cure me of my GAS but rather to crack the code of it. I arranged a meeting with the manager of Mental Health Services at Concordia University in Montreal, Dr. Jeffrey B. Levitt, and decided to see if he could help me finally snatch that damn pebble out of that calloused ol’ hand.

Dr. Levitt isn’t your everyday quackery-spouting egghead. He’s actually one of us. About a baritone neck away from his framed psychology license in his office is a calendar boasting all of the solid lumber coming out of the Fender Custom Shop. On top of his desk, where other psychologists might have a Newton’s Cradle of clacking steel balls, he has a nickel-covered set of Throbak humbuckers. Dr. Levitt’s quest for tone has led him to a ‘92 Fender Custom Shop Telecaster that he plugs into a 65amps London head with a matching 2x12 cab, but his quest for tone remains as insatiable as mine.

“Very few people actually attain what they are desiring,” Dr. Levitt told me soon into our conversation. He went on, laying a clear foundation of thought from which we’d further poke and prod, “People will get a Gibson and a great amp and create a great sound but it’s never satisfying enough. To use an analogy, vanilla is great and is probably the best ice cream flavor but you when you see strawberry and chocolate and other flavors you have to dip in and attain it. The sonic vocabulary is so vast that once you get one type of tone it remains to be only one paragraph of one chapter of one story. I know people who are just crazy about fly-fishing and they will just obsess with water temperature, the type of fishing line, altitude, etc. and it’s no different from being a guitar enthusiast. Once you become passionate about something, the quest is never over. The quest, though, proves to be even more enriching than reaching the ultimate.”

I actually followed that. Bought it, too. From there, we both knew where this was going. I had more questions, and it was clear that with his background as both a tone junkie and a psychologist, I had the right person to ask.

Where’s the Rub?

Usually, the seed of a guitar sound I want to attain is planted by a favorite record. The inspiration for the aforementioned Les Paul/Marshall revelation came directly from Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak record. As soon as I heard the midrangy crunch of the twin Les Paul and Marshall pairing on the title track, I was hooked and so it began. Quickly, my stock Gibson “Shaw” pickups seemed thin in comparison with Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson’s twin attack. I have now had every pickup combo imaginable in that guitar and have gotten the closest with a bone nut, TonePros aluminum tailpiece and bridge, RS Guitarworks pots and capacitor, and a WCR coils American Steele set of pickups. I truly love the sound of that setup, but you guessed it—I’m still not holding the Thin Lizzy cigar. I know I’m not alone in having a story like that.

“The more glorified an artist is, the more people will want to attain that fame, beauty and sound,” Dr. Levitt said. “We want to say that the tone is in the fingers but it’s very difficult to measure that and recreate that, so we go to other measures to attain cause and effect. Especially with signature series instruments, there is a fallacy that we will get this one-to-one correspondence with the person who inspires us.” I believe that on some level we all know what Dr. Levitt is referring to; we just don’t want to admit it.

“What does happen, though, is that these artists will provide a path,” Dr. Levitt suggested with a smile, “and as interests in other tones broaden, we will inevitably synthesize these tones and that’s where our own signature sound starts appearing.” My own signature sound? The longer I thought about that, the heavier that concept became.

Yes, Jazzmaster

Most of my amp, guitar and pedal choices are based on records I have become emotionally attached to. I want to recreate those emotions in my own playing. Television guitarist Tom Verlaine’s clean, angular and outside jazz guitar lines truly inspired me and had me researching his gear and finally hunting down and procuring a ’66 blackface Super Reverb and a pair of Jazzmasters (seafoam green’61 and a transitionyear tobacco ’65). Do I sound like Tom Verlaine? Not even close. Do I love the sound of my ’65 into the Super Reverb? Let’s just say I know that the hair on the back of your neck will stand at attention when I tear into “Marquee Moon.”

Oddly enough, before I was on a Verlaine trip my obsession with Jazzmasters came from guitarists like Sonic Youth’s Lee Renaldo and Thurston Moore and Dinosaur Jr.’s J Mascis. These mavericks were trying to remove themselves as much as possible from the classic Page, Clapton and Hendrix tones that a plethora of players were trying to shoulder up against. Another thing that I now see clearly is that my infatuation with classic Jazzmaster tones was a blessing for me as well as for other less financially endowed riffmeisters. The Jazzmaster’s doormat reputation had something to do with the slim price tag attached to its extra wide head stock. Heck, that could have been the same reason that threadbare rockers like Renaldo and Mascis’ gravitated towards them.

Elvis Costello with one of his beloved Jazzmasters in 1977. The Jazzmaster’s story, especially the rising price of vintage Jazzmasters, can teach us a lot about the psychology of tone. Photo by Bob Leafe/ Frank White Photo Agency. |

“Guitars like Steinbergers and Parker Fly guitars are amazing playing and sounding guitars but are hardly going to topple the sales of Telecasters, Les Pauls and Stratocasters, because they just don’t have the same aura,” Dr. Levitt surmised. “In the end, there will always be identification with what we glorify, and there will be iconic sounds and images in our collective conscious that we respect, value and seek. We want that connection to a story and if we peek behind the curtain and just see a washboard with a plank of wood stuck on, it loses a bit of the magic—and that’s what we’re after.”

Although many of us don’t want to admit it, Dr. Levitt’s theories do dredge up some truth. One has to look no further than the fetishists who are knocked to their knees when talking about the Peter Green/ Gary Moore ’burst, Roy Buchanan’s “Nancy”, Billy Gibbons’ “Pearly Gates,” Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “Number One,” Clapton’s “Blackie,” etc. Are those aficionados aware of how much they love the associated narratives behind those guitars, or is it truly the tones—and only the tones—that they’re after?

True Relics?

Truly famous guitars are famously dinged, and that helps differentiate them from other instruments while adding the realistic side of romance to the equation. True love survives wear and tear; it lasts. The problem is, most of us are incapable of working SRV “Number One”-level love into our guitars, emotionally and physically, but we want to participate in this “older is better” way of thinking. Accidentally or purposely putting a gank or two in your otherwise new Strat just isn’t the same—a weathered guitar has to look like it has been played by a pro for a long, long time. That’s why many companies offer a controversial relic’d version of their classic lines these days.

If you ever want to see two guitar fiends screaming bloody murder at each other, just bring up the topic of relic’ing. People get awfully testy when it comes to guitars bearing chemically treated and artistically abused armor. It makes sense that this is a sensitive issue—the fake beat-up look threatens the sanctity of an aesthetic that, until recently, was reserved for guitars that were authentically worn in and lovingly coaxed into producing todie- for tone over long periods of time. Those are rare guitars. Naturally, one side of the debate is very protective of that authenticity.

“We are programmed as humans to be drawn to stories and characters, and if there is no story we tend to find it less sexy,” Dr. Levitt confirmed. “For the most part, guitar players think ‘the older the better,’ and that’s partly because quality control was better at a lot of the major manufacturers in the fifties through the early seventies. Despite quality control lacking in the mid-seventies people will still pay vintage prices for these guitars, even though they may not be as well made as guitars are today. These beat up guitars tell stories, so when we see the relic’d look it triggers the mind to question how that happened and the mind begins to fantasize. When we pay for a relic’d guitar, we’re paying for a fantasy … unless you’re psychotic, you don’t actually believe that you’ve been on numerous tours with this brand new guitar, but you are now able to imagine that.”

There’s No Crying in Tone Hunting

Set aside the fact that certain eras had better manufacturer quality control and consider that there’s also an emotional connection with older music. It has endured the test of time and begat new generations of tone, therefore it rates higher on our tonal respect charts. Page’s “Black Dog” tone holds a certain nostalgic value compared to the guitar sounds anyone can crank out with digital tools these days.

“People seek comfort with the familiar, the tested, and with stability.” Dr. Levitt offered, displaying the kind of trained mental objectivity that unlettered tonehounds will struggle with. It’s much easier to simply swear that those old tones are downright “better.” No one wants to be told that their emotions are coloring their opinions about actual tonal “quality,” if there is such a thing.

“Perception is very tricky and relative,” Dr. Levitt continued. “A guitar could look like a piece of junk and be butt-ugly but may possess unbelievable tonal qualities due to the wood, construction, and other variables. But … I’d rather play a Tele, Strat, LP, or Rickenbacker, even if they’re sonically inferior, because I am enamored by their looks and history. That is, it makes me play better because I feel better about playing them. It’s a feeling that you’re a part of history, a part of a group, a part of a family—be it Fender, PRS, Gibson, etc. The “feeling” part and issues of connectivity and attachment… that’s all psychology.”

True Believers

I suspect you’ve called BS on some part of this article by now, and that’s fine. Surely there is such a thing as superior tone, psychology notwithstanding… right? Personally, I can’t say that I’m over my fixation with tone now that I’ve had a chance to chew on these pointy-headed concepts. I must say, though, I really do feel closer to whatever it is that I’m looking for. I haven’t reached that tonal destination yet, but looking back I know I’ve saddled up a bar stool next to it and shared a pitcher of draft with it.

If there is anything I’ve learned from our mutual unpeeling of the layers of the tone onion, it would be that the journey is far more enriching than the actual destination. Dr. Levitt suggests that much of this has to do with our natural inclination to seek out the explainable. In some way, our quest for Holy Grail tone is an enactment of our thought process. We want to reduce ambiguity. We try to frame everything within the parameters of cause and effect. We may not find the cause, but we get a good snootful of the roses every now and again, so we dutifully put our one foot in front of the other and continue down the winding path to eargasmic tone. It’s these prickly plants and their sweet aroma that make this whole trip worthwhile.

My eyes remain fixated on that perfect pebble. I’m still helplessly trying to grasp it away from the tone master, but in the back of my mind I also secretly hope to remain hamfisted and slow to grip. The day we are finally able to grab that elusive pebble could be a sign that our passion has truly run dry.

Next month—don’t miss part II, The Science of Tone, in which we ask the question: Isn’t our fixation with PAF and Nocaster tone kind of like a car buffs swearing that the Model T had the best-running engine ever made?