Matt Sweeney thinks you should fingerpick. "I don't want to sound like some sort of dick who hates guitar picks," he says, after about 20 minutes railing against guitar picks. "But try it. It's worth it."

Sweeney is passionate, and when given a soapbox he doesn't hold back when he's advocating for something he believes in. Otherwise, he's self-effacing and humble. For example, check out the Guitar Moves video series he did a few years ago for Noisey, the music site for Vice. Besides becoming something of a household name (at least in nerdy, guitar-obsessed households not already familiar with his extensive and impressive discography), in each episode he threw himself headlong into a situation that, at best, was painful and awkward as he learned a new concept or technique for the first time live and on camera.

"Being awkward and vulnerable, that's like being alive," he says. "I think music is all about harnessing your horrific, awkward vulnerability, and working on it and working on it and turning it into something that sounds confident and makes other people feel that they aren't so awkward and vulnerable. That's an illusion, but it's an illusion as much as art is an illusion, meaning that you work really hard to make it easy for somebody else. To make somebody else feel at ease."

Harnessing vulnerability may also explain Sweeney's particular guitar-related passions. In addition to fingerpicking, he has strong opinions about things like flatwound guitar strings—he loves flatwound guitar strings—and not using pedals.

Matt Sweeney & Bonnie 'Prince' Billy "Make Worry For Me" (Official Music Video)

But his first passion is fingerpicking, which he learned how to do after he was already established. By that point, he was a seasoned road dog with thousands of miles under his belt with underground bands like Skunk and Wider. He also had a number of recording credits to his name and had gone on to greater recognition as a founding member of Chavez. But then he realized there was more than one way to skin a mudskipper.

"I was in Chavez, and on a lark I went to a festival called the Charlotte Bluegrass Festival—it's like a real old bluegrass festival in the middle of Michigan—and seeing people fingerpick blew my mind," Sweeney says. "A friend of mine, his name is Sam Dylan, had already figured out how to play a couple of Mississippi John Hurt songs, and he was also really adamant about fingerpicking. His attitude was, 'If you're not fingerpicking you're just fucking around.' He showed me two patterns, which are both Mississippi John Hurt patterns."

Fingerpicking for Sweeney was transformative, both as a musician and as a person. "At that point, I thought I was an okay guitar player, and I'd already made a bunch of records," he says. "But just trying to do those patterns was so humiliating that it definitely made me understand why rock guitar players don't fuck with fingerpicking. I decided to stick with it. It was such a challenge and so remarkably humiliating to sound incompetent on something that used to be my passport into feeling cool. But after seeing my friend do it, and after he showed me the patterns—I have a very clear memory of it—I thought, 'If I get this, I am going to have a voice and I am going to have a way of playing guitar that is undeniable, and it's going to sound really good, and not a lot of people can do it.' It took like a month, which is nothing. It's humiliating, but it doesn't take that long. I really do think that the undoing of your confidence is such a no-go zone for people, and so many people play music precisely for the reason that they can feel in control. Fingerpicking changed everything. I can't recommend it enough."

TIDBIT: The new follow-up to 2005's 'Superwolf' took 16 years but was recorded with immediacy in mind. "Eye contact is key for recording anything," Sweeney says. The album art is by Harmony Korine.

Sweeney's first recording without a pick is the song "Salty Dog," recorded with the singer Cat Power for her album The Covers Record. The song is a duet—voice and guitar—and his part is based on a pattern he learned from Dylan. It was also around that time that his interest in fingerpicking collided with his burgeoning collaboration with vocalist Will Oldham (who often records under the moniker Bonnie "Prince" Billy), and which led, eventually, to the birth of their duo, Superwolf.

"Chavez wasn't playing much anymore, and I had befriended Will Oldham," Sweeney says. "Will was one of the first people who heard me fingerpick. We became friends, a guitar was sitting around, I picked it up, played something, and Will said, 'That sounds good.' I said, 'Right, that's the whole point of fingerpicking … to make somebody say, 'That sounds good.'"

That revelation wasn't arrogant or self-centered. It was grasping a deeper truth intrinsic to music, which, for Sweeney, is inextricably linked to fingerpicking.

"Really, that's the point of music: to get people's minds off of whatever and to hypnotize them a little bit," he says. "That's when I thought, 'Cool, I did the thing that I wanted to do. I can fingerpick now and I can play with a really great singer who is working in an idiom that I hadn't worked in before.' I started playing with Will and that gave me the opportunity to keep developing the way that I was playing, because it went well with his singing. After a couple of years, that led to Will suggesting that we write songs together."

Matt Sweeney's Gear

Matt Sweeney's 1969 Martin D-18 (a gift from Neil Diamond)

Guitars

• 1969 Martin D-18 (a gift from Neil Diamond)

• 1976 Gibson ES-335TD

• James Carbonetti Savagist Bo Diddley-style guitar

Nuñez Amplification Dual Range Boost

Amps

• Austen Hooks converted Bell & Howell projector amplifier

• Will Oldham's Music Man HD-130

Effects

• Nuñez Amplification Dual Range Boost

• Echopark F-1 Germanium Fuzz

Strings

• La Bella Jazz Flats (.012–.052)

• D'Addario flatwounds (.012–.052)

Those songs became their first album, Superwolf, which was released in early 2005. Their duo is very much a modern take on the low-key, fingerpicked albums of yore. "Will's songs come out of that tradition of English-style and Appalachian fingerpicking," Sweeney says. "It's a nod to that. Will doesn't try to be a retro artist or throw around the term authentic, or anything like that, but his music is absolutely rooted in Scottish folk songs."

That first album also features the drummer Peter Townsend ("the real Pete Townsend," Sweeney says) and guest vocalist Sue Schofield. It took 16 years, but the follow-up, Superwolves, was released at the end of April. In addition to Townsend's return, it features a number of guests, including Tuareg guitarist Mdou Moctar, members of Moctar's touring band, and other friends from Nashville and Brooklyn. The music is understated and relies heavily on the interplay between Oldham and Sweeney. They tracked live and made sure they could see each other. "Eye contact is key for recording anything," Sweeney says.

The tuning Sweeney uses with Superwolf is an important part of the band's sound, too, even though he doesn't often stray too far from standard. "With Superwolf, most of the songs are in a tuning that Will and Lou Reed used a lot, which is just standard tuning, but it's in D," he says, noting that every string is tuned down a whole step, although otherwise it looks and feels like standard. "I don't understand why it isn't more of a normal thing to do, because it immediately opens up different possibilities, and that's sort of why the Velvets sound really cool."

Producer and industry legend Rick Rubin was a fan of that first Superwolf album and invited Sweeney to play on sessions. Over the years, Rubin has used him in numerous situations, including some you might not expect, like with superstars Neil Diamond and Adele. But Sweeney's first gig with Rubin wasn't as seemingly incongruous. It was on the first posthumous Johnny Cash release, American V: A Hundred Highways (Sweeney also appears on American VI: Ain't No Grave). It was through that project and hanging out in the studio with some of Cash's longtime sidemen that Sweeney encountered what was to be another passion: flatwound strings.

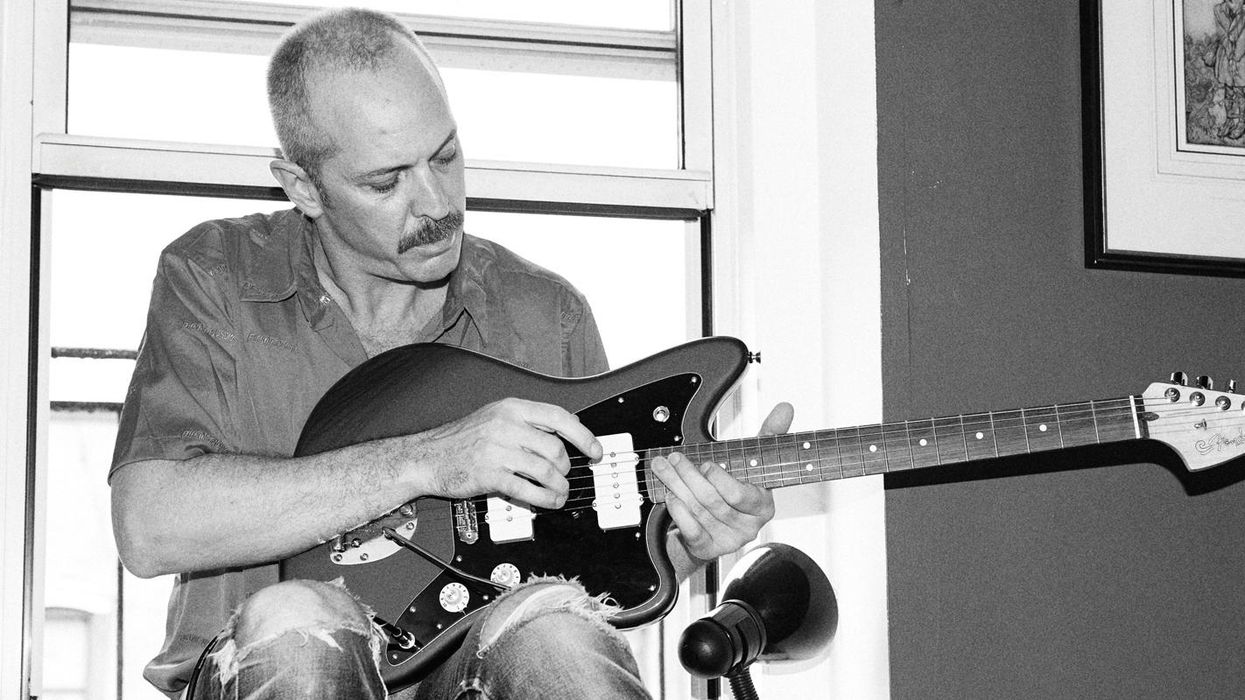

Matt Sweeney's career amalgamates an uncommon blend of indie- and roots-rock-cred, high-profile session gigs, membership in the Billy Corgan-led supergroup Zwan, and collaborations with Josh Homme and Bonnie "Prince" Billy.

Photo by Chris Shonting

"I got asked to do sessions for Rick Rubin, and I had no idea what to do at all," Sweeney says. "I chose to bring nothing with me—because I knew his studio had tons of guitars—and sure enough, all the players on the sessions were using flatwound strings. Okay, I won't say all of them, but certainly Smokey Hormel was. I think I picked up an acoustic guitar. It had flatwound strings on it, and I said, 'This sounds amazing.' Smokey said, 'Yeah, dude, you have to use flatwounds if you're going to make a good-sounding record.' I said, 'Nobody ever told me that.' He said, 'Nobody ever does.'"

For Sweeney, flatwound strings are an aesthetic link to the history of guitar-based music. "Roundwound strings weren't widely available until 1970," he says. "Every damn recording you've heard is on flatwound strings." [Author's note: Sort of. According to AcousticMusic.org, Pyramid, based in Germany, started selling the first set of pure nickel roundwound strings in 1954. In the U.S., roundwound strings became commercially available in the mid-1960s, and most manufacturers offered them by 1970. The Beatles, mentioned below—and this is argued endlessly in various online forums—most likely used flatwound strings on their early recordings, but by their final period were probably using .010-gauge roundwound strings, like many guitarists today.]

"Remember when you were first playing guitar and put on a new set of strings? Remember how cool it would sound? I don't really like that sound," he laughs. "But it's bright and shiny. String up your guitar with flatwounds and start playing along to Beatles' songs. 'Oh, there's the sound.' It's wild! It's such a quick hack to getting a cool tone. It also makes your guitar playing totally different, because there is zero resistance when you're moving up and down the strings. There's no squeak. You get this new lease on life on guitar. The tradeoff is you don't get the shiny bright sound and the action is a bit higher. But on the positive end, it sounds so good and it records really well."

Sweeney has an opinion about getting great tone, too, which, for the most part, doesn't involve pedals. "I don't know any other way to get a tone other than from your amp and fingers," he says. "Otherwise, you're not getting your tone, you're processing your tone. That's another thing that fingerpicking brought out: Your right hand is your mouth. That's what's making the sound come out. But again, speaking of tone, we seem to largely agree that the guitar recordings everybody freaks out about are usually from before the '60s. They're using flatwound strings, they're not using pedals, and it sounds really great."

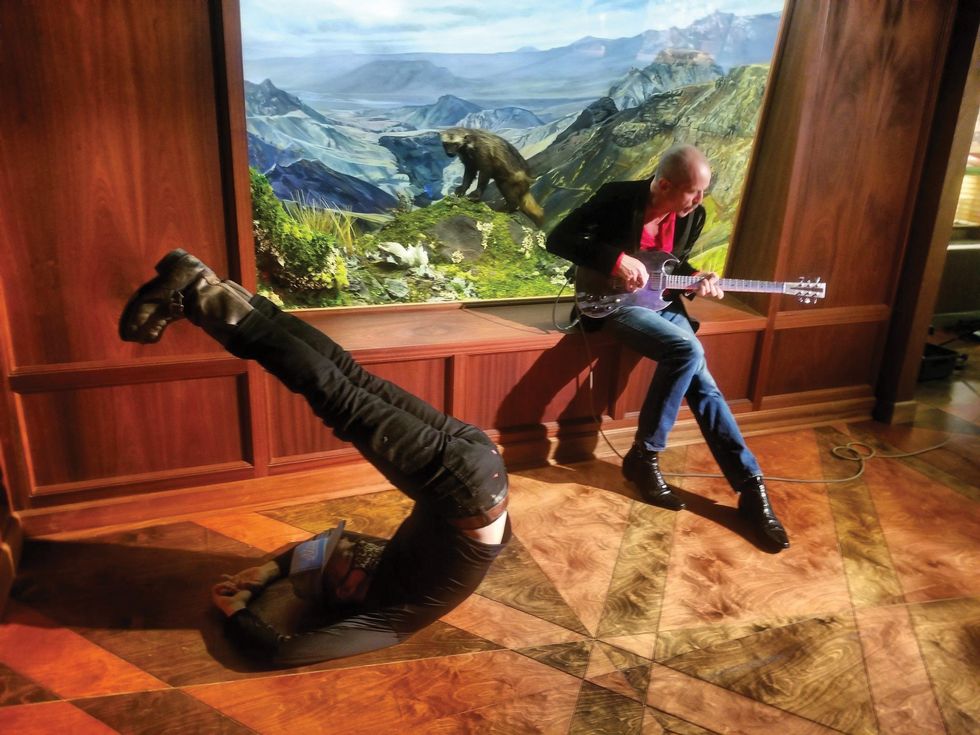

The Superwolf duo of Sweeney and Bonnie "Prince" Billy, on the floor here, allows both players to explore their most traditional instincts, and was built on friendship that bloomed into a musical project. Any wolverines in the photo are purely coincidental.

Photo by MXLXTXV

But Sweeney isn't opposed to pedals, and, unlike fingerpicking, his relationship to pedals doesn't involve deeper philosophical issues. He also understands how sometimes they're essential to standing out in a mix. "I love pedals. Pedals are really cool, and they're fun," he says. "But I established the way I sound without relying on pedals at all. Although over the last couple of years, I've been amassing range-driver-sounding pedals, which I now have a bunch of. That's something I picked up from Josh Homme. He pointed out, 'Get any kind of pedal that will make the sound wave a little different.' Pedals that put things out of phase and make it poke out a little bit are cool."

Still, ultimately, he asserts your sound is in your fingers. "The whole thing is, turn up the amp really loud. Since you're not using a pick, you have a lot of control over your attack. You can bear down on it, hit it harder, hit it softer. That's the sound. You get shitloads of drama that way. You can get all these cool things that people talk about with tone that sound really beautiful because you're fingerpicking and the strings are ringing against each other and you're controlling the volume. It's cool, and it really works."

Fingerpicking, flatwound strings, coaxing great tones from an overdriven amp—none of those things are easy, but that, similar to purposefully filming himself in awkward, vulnerable situations, is how Sweeney operates. He's not looking for shortcuts. He's following his passions, and, as best he can, keeping it real.

"Definitely the reason I got into playing guitar was because I thought it would be kind of easy," he says. "It's easy to sound good on guitar, and that's what's really rad about the guitar. Other than being a good singer, I think it's probably the cheapest way to get musical and to start making a sound that feels good. You learn a couple of guitar chords and it's exciting. You could pick up a guitar and in a day you can sort of do a facsimile of whatever crappy song you think is good. But then you're kind of ignoring the fact that you're not really going for it, and not really challenging yourself. I've always found that guitar players will say, 'Oh, fingerpicking is like classical guitar.' But that's just a catchall term for all the guitar playing that you don't understand [laughs]."YouTube It

In this episode of his 'Guitar Moves' series, Matt Sweeney gets a typically humbling lesson in the style of Mississippi Fred McDowell from Dan Auerbach, on acoustic guitar.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)