All photos by Michael Bloom Photo, michaelbloomphoto.com.

With its expansive mountain views, gourmet dining options, and rustic accommodations, the Full Moon Resort (located in upstate New York’s Catskill Forest Preserve) is the picture-perfect image of calm. But it was closer to sheer terror than tranquility for the nearly 100 guitarists lined up for their chance to jam with guitar virtuoso Paul Gilbert at his 2013 Great Guitar Escape, held from July 8–14. Participant Steven Schwartz, an owner of a local music store and a ridiculously accomplished shredder himself, succinctly described on Facebook what it was like to have every lick he threw at Gilbert deflected and answered with the most lethal of sextuplet-laced blows: “Dear Diary, today I got to trade solos with Paul Gilbert for 45 seconds. Heart is still racing, hands are still shaking ... and it's been over two hours since it happened.”

The few hours that Schwartz remained in shock pales in comparison to the time it took some of the participants to complete the long journey to the resort from places as distant as Germany, Amsterdam, Canada, and even Brazil, from where three friends came together for a once-in-a-lifetime trip. Although one of the Brazilian gentlemen had stern orders from his wife demanding that he not come back with any guitars, along the way to the camp, the trio made a pit stop in New York City and couldn’t resist the temptation to pick up a Suhr axe and a Fender Cabronita Tele.

The Great Guitar Escape’s faculty was personally chosen by Gilbert and consisted of rocker Andy Timmons and jazzer Mimi Fox (both Favored Nations artists), Berklee College of Music associate professor (and co-author/instructor of Berklee’s online course, Steve Vai Guitar Techniques) Scotty Johnson, blues slide master Tony Spinner, and internet tapping/double-neck sensation Adam Fulara (who Gilbert found on YouTube and imported all the way from Poland). “The people I chose are people that I’m also interested in as a student,” admitted Gilbert. “I have so much respect for them that I feel a little reluctant to be the boss. I feel like they’re as good as me, if not better. But somebody’s got to do it. Somebody’s got to drive the bus, so okay, I’ll grab the wheel.”

Paul Gilbert discusses his list of essential listening songs.

With Gilbert’s name on the marquee it’s easy to automatically assume that the Great Guitar Escape would have been a weeklong orgy of three-note-per-string scales and string-skipping arpeggios, but surprisingly the shred aspect represented only a fraction of the week’s curriculum. The classes touched on all facets of guitar playing and there was a great balance of topics to choose from. The vibe of the teachers ranged from informal—Spinner’s classes featured Gilbert interviewing him—to ultra-egg headed. Fulara’s class was virtually a treatise on music with a dense, five-page text handout titled “Elements of Music-Overview,” which featured a bizarre, low-brow-meets-ivory tower juxtaposition of the Cranberries “Zombie” as a Cantus Firmus in a counterpoint example. Such variety made the intense dawn to dusk schedule survivable.

Premier Guitar was there to participate in the festivities, sample some of the classes, and give you a firsthand glimpse at what it’s like to take part in the ultimate guitar getaway—complete with a short lesson from Timmons and Gilbert at the end of this article.

Groove 101 with Scott Johnson

Scott Johnson—Going “Outside” with Rhythmic Intention

Scott Johnson’s storied career spans the gamut from recording with artists like Gilbert and the Ford Blues Band (featuring guitar phenom Robben Ford), to battling it out in the trenches as a first-call session ace. His class focused on the crucial skills a working musician needs and started with a look at the subtle but oft-overlooked components that separate the men from the boys—like dynamics (loud and soft) and duration (short and long). The importance of having solid reading chops was also emphasized. “I've never seen tablature on a gig,” said Johnson as he began demystifying the overwhelming possible combinations of notes and rhythms that paralyze many would-be readers from jumping into the waters. “You see a lot of the same rhythms over and over again, and if you read enough you will start to recognize these rhythms.”

To acquaint the students with some key rhythms and to zone in on the importance of playing in the pocket, Johnson microscopically analyzed all the possible 16th notes in a beat. He had students repeat an attack on each 16th hypnotically against an amplified metronome until it was locked in and grooved. After this felt solid, he broke the class up into sections and had each section play only one part of a 16th note rhythm. Once the class settled in nicely on the vamp, Johnson soloed against the class, at times deliberately manipulating his phrases to make it a real challenge to not get thrown off. No matter how much Johnson displaced his phrases rhythmically, the class held strong and in a little more than an hour, everyone appeared to understand what it means to play in the pocket.

A student (left) opts for a private lesson with instructor Scott Johnson (right).

Mimi Fox—Creative Jazz Improvisation

When you think of a Paul Gilbert camp, chord melodies and Wes-style octaves might not be the first thing that comes to mind, but Gilbert insisted on having a bona fide bebopper on board. “I wanted to get someone that was a really solid jazz player,” says Gilbert. “I hadn’t heard of Mimi so I just Googled “Best New Jazz Artist” and came across her. She’s also on Steve Vai’s label. When I see her play, what she does is so advanced that it just blows my mind. I’m fairly intimidated.”

Almost immediately upon arriving to the resort, Fox formed a bond with Timmons, who recently had the bebop fire re-ignited. For many of her classes, Fox had Timmons join her onstage, and she reciprocated during his classes as well. This made for many exciting musical moments.

Starting off with the nuts and bolts mechanics, Fox talked about key scales, both common (Mixolydian, Lydian b7, whole tone, and diminished half/whole) and uncommon (Byzantine—a harmonic minor scale with a #4), that every jazz player should know. To put it all into context, she improvised lines with these scales as Timmons comped chords, and all ears in the room perked up as they heard the biting tensions these new-to-many scales produced.

Andy Timmons is mesmerized by Mimi Fox's solo guitar stylings.

A point she reiterated often was that she initially learned these colorful sounds by ear after transcribing classic solos from the masters. “Like a mad scientist I would write all this stuff down,” said Fox. She then played through selections she’d transcribed back in the day including Wes Montgomery’s head and solo on “Cariba,” and Pat Martino’s solo on “Lazy Bird.”

Fox was very forthcoming. When a student asked her if she ever messes up onstage, she said, “Honestly, you never stop paying your dues.” She then recounted seeing an iconic jazz piano legend add an extra "A" section to the standard, “Seven Steps to Heaven,” thereby screwing up the form of the tune. That’s the type of mistake that, on the surface, might seem innocuous, but to a jazz player it might result in the pink slip. The class rounded out with Fox and Timmons performing a hyper-burning rendition of Charlie Parker’s “Donna Lee.”

Andy Timmons discusses how the study of bebop has informed his rock playing.

Andy Timmons—Rock Phrasing Workshop

Taking a less technical teaching approach than Fox, Timmons’ strategy was to show by example and he emphasized his points by playing along to pre-recorded backing tracks for a large portion of the class. He talked about the musical finesse that he garnered from his jazz studies early on and demonstrated via intricate chord melody arrangements of several Beatles tunes, as heard on his release Andy Timmons Band Plays Sgt. Pepper. “Although what I learned was in a jazz context, I was applying it to pop music,” says Timmons. “I may not play bebop licks all the time but how I think is very much informed by the jazz players—things like voice leading, note choice, and chord tones or non-chord tones.”

Timmons offered sage advice to his students about polishing their playing and creating a unique stamp on their instruments. “I call developing your own voice, editing. You know The Beatles were great editors. They learned a bazillion tunes and when it came time to write their own songs they had a library in the back of their heads, ‘Oh yeah, I like that chord change,’” says Timmons. “Stevie Ray was a great editor. He took the best of Albert King, the essence of Jimi Hendrix and all the great blues players but it was about the way he packaged it. It’s about finding the things that connect with you emotionally and applying them to your own thing. It doesn't matter how many words you know, it's how you use them.”

The mood was lightened many times by Timmons’ humorous antics, such as singing the Gilligan’s Island theme over the “Stairway to Heaven” intro riff. The laughter stopped, however, when Timmons closed out the class by performing the jazz standard “All the Things You Are” with Fox in a jaw-dropping, contrapuntal baroque style piece with both artists improvising flowing eighth-note lines that thoroughly nailed the changes.

Gilbert enjoying his time offstage in the audience.

Jam with Paul

Gilbert’s course offerings included “Scales and Arpeggios for Rock Guitar” and “Songs, the Best Guitar Teacher for Rock,” but by far the class that got everyone the most excited was “Jam with Paul.” After all, how often does anyone get to trade licks with a rock guitar icon?

You might think the jam session would turn into utter chaos with so many guitarists in the house. To the contrary, the jam was amazingly well organized. Ibanez’s repair team leader Mike Arellano was on hand to keep the line moving by removing and passing on the silent switching cable after each jammer had his shot. The first jam of the week consisted of sparring with Gilbert over an eight-measure A7–D7 vamp with everyone getting three rounds of the progression to blow on.

Although the jam session wasn’t a traditional class in the sense of information dissemination, for many it provided the best learning experience of the camp because it threw them right into the lion’s den. “You suddenly realize that, no matter what you’ve got as far as fast or slow, or whatever, you’ve got to be able to squeeze it into a framework,” says Gilbert. “A framework of tempo, a framework of harmony, a framework of accents—accents that you either want to match or play against and create syncopation. There are great guitar players who never think of those terms, they just feel it naturally. But there are also so many people—including myself—who … there are lots elements of music that took me way too long to discover. I hope that experience left a mark on everybody.”

Paul Gilbert gets inside information from Tony Spinner.

”Scarified” to Stevie Wonder

Every night was capped by a stellar concert with Gilbert and faculty. The song selections throughout the week’s concerts—The Bee Gees’ “How Deep is your Love,” Gary Moore’s “Still Got the Blues,” ABBA’s “Dancing Queen,” and Stevie Wonder’s “Sir Duke,” among many others, reflected Gilbert’s recent interest in playing over changes. “The Stevie Wonder tune I played the other night goes from A major to Ebm7—a minor 7 chord a tri-tone away! I’m just the happiest person in the world listening to it and dealing with the challenge of soloing over it,” says Gilbert, who also picked up a Rickenbacker bass several times throughout the week for select cuts.

For the diehard fans who’d rather be dead than live without shred, Gilbert performed “Scarified,” his signature face-melter that he popularized during his Racer X days. During the performance, Gilbert asked for a do over of the insane arpeggiated middle section, just to nail it flawlessly.

Mimi Fox trades licks with Adam Fulara over a one-chord vamp at the all-star faculty concert.

Happiness from Happenstance

For many attendees the best part of the week was what transpired out of pure happenstance. Having the good fortune to have Gilbert, Timmons, or any other of the stellar faculty members end up on your roundtable during one of the three daily meals led to priceless conversation, which, for many, proved to be just as educational and entertaining as the classes themselves. Gilbert told a table of students with plates full of mustard seed-crusted salmon: “I thought of an amazing exercise. Play ‘You Really Got Me,’ which starts on the “and” of beat 4, but start it on every possible downbeat and every possible upbeat. You can do downstrokes or whatever; I’m not worried about the technique. It’s a rhythmic exercise. Your playing hasn’t changed at all, but it’s changed in reference to where the foot is. The idea is to mentally shift it, like you do in ProTools when you move something over and drop it in another spot.” That sounded simple enough—but when I got back to my room and tried it, I struggled through feeling like an uncoordinated klutz.

It wasn’t just random chances to hang with these guitar heroes that made the week special. Some lucky students had the opportunity to jam with them. One kid was just noodling on a hollowbody in the lawn when Timmons invited him back to jam. Mimi Fox also joined in and the kid got perhaps the most intense lesson he’d ever encountered in his life. Even if it wasn’t a jam with an established pro, there were daily round-the-clock unsupervised student jam sessions in three locations where everyone had a chance to strut their stuff.

Mimi Fox shows an eager student some blazing lines.

The Grand Finale

To top off the week, there was one final open jam with Gilbert. To make it even scarier, they pulled out all the stops and enlisted Timmons to play bass. The structure was an E blues and the students would trade licks with Gilbert every two measures for a total of two choruses each. I decided to take the plunge and join in. To be honest, initially, I wasn’t really scared. But the more I listened to those around me—both teenagers that practice eight hours a day and successful corporate business dudes—expressing just how terrifying of an activity this was, their anxiety rubbed off on me.

Probably like everyone else in line, I had some grandiose fantasies of what this moment was going to be like. However, when my turn actually came up, reality came crushing down, and instead of whipping out the 16th-note sequences that I planned on, I opted to play it safe and avoid trying to get into a guitar battle that I’d have no chance of winning. Before I knew it, my turn was over. At that moment, all I could think of was practicing like a madman for the chance to do it again next year. It then dawned on me why so many of the attendees are return students, and why the three Brazilians had already made plans for attending Gilbert’s next Great Guitar Escape.

LESSONS

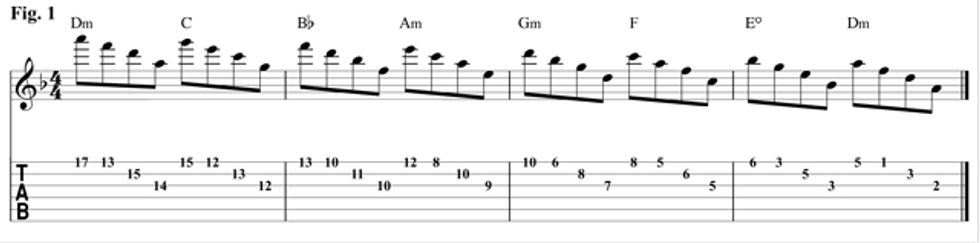

Andy Timmons

When I learned the modes I never thought they were different scales. We’re always learning things in position but I do things that are a lot more horizontal than vertical. To me it’s just more lyrical and vocal sounding. What it did for me was show me the possibilities. I could be playing “Cry for You,” which is just in D minor but I relate it to F major.

This is how I apply a modal approach to this chord progression. It’s just diatonic triads—D minor, C major, Bb major, A minor, G minor, F major, E dim, D minor—just triads right down from the D minor or F major scale.

Paul Gilbert maps out wicked arepeggio shapes on the whiteboard.

Paul Gilbert

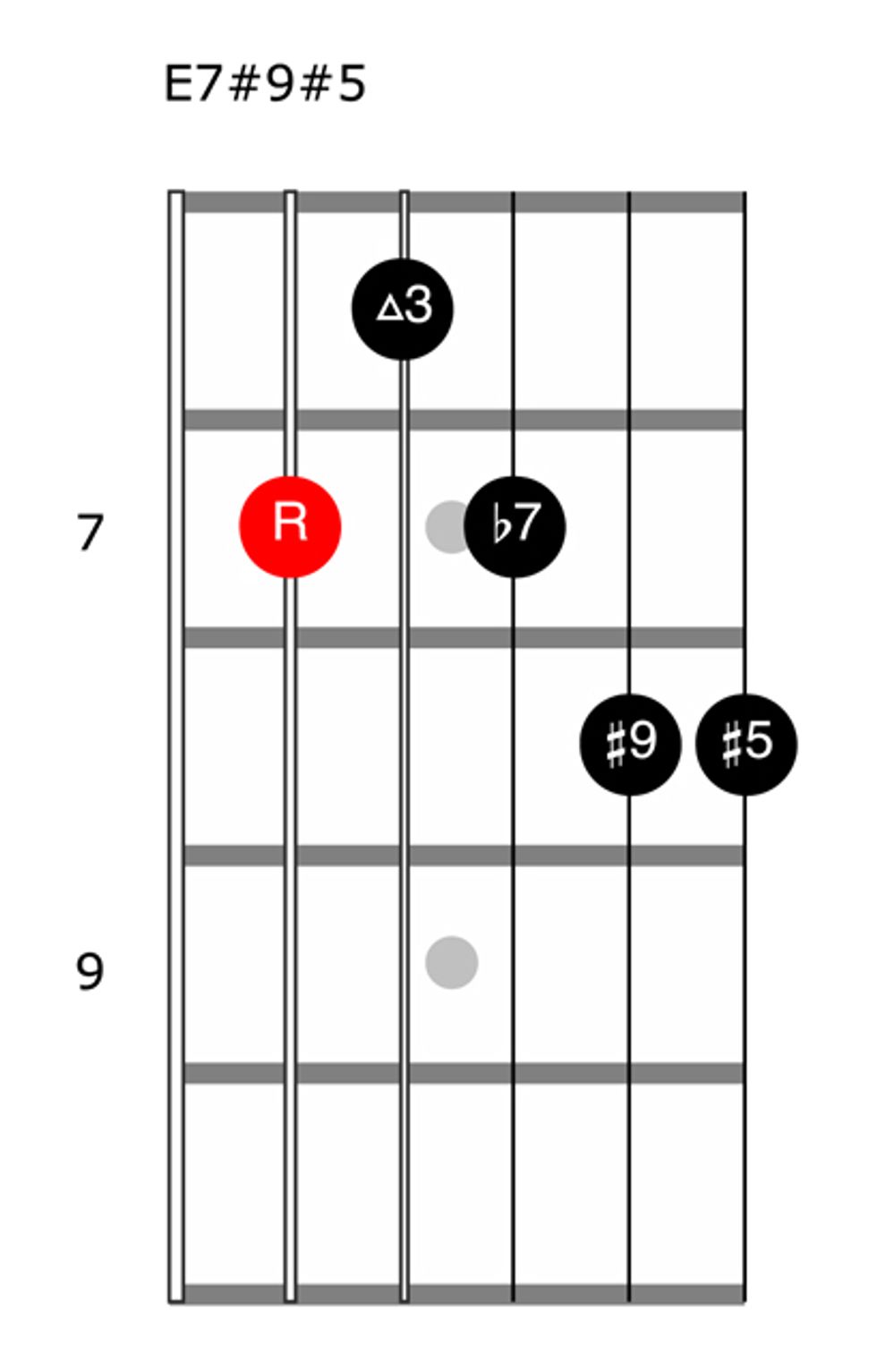

Give a jazz player an E7#9#5 chord and the first thing he’ll probably do is whip out the Super Locrian scale. Paul Gilbert’s got a more direct way to navigate this scary-sounding chord. “I’ve heard that term Super Locrian, but to me it’s just the notes of this chord [plays E7#5#9],” says Gilbert. “A big breakthrough for me mentally was realizing that I don’t have to play every note in a scale. If I leave some out and pick my favorites, it aims the sound much more harmonically accurate. Whereas if I play every note in the scale you can have the right notes but you’re not having as much harmonic intention.”

Perhaps the most common guitar voicing of the E7#9#5 chord is played as the Jimi Hendrix chord with an added note on the 1st string. From bottom to top the notes are E–G#–D–G–C.

Gilbert takes the notes of the voicing and arranges them in alphabetical order, configuring the notes in a finger-friendly pattern. “Instead of being spread out in a chord voicing, here they’re stacked up consecutively,” says Gilbert. “That’s me dipping my toes into the pool of jazz. This is really an interesting way of forming scales and arpeggios.”

A recent lightbulb moment also paved the way for more of Gilbert’s thrilling sonic shapes. “My wife has been practicing jazz piano at home and she was just playing the chords very methodically to learn them,” says Gilbert. “I noticed that she wasn’t playing the roots in the upper voicings. That helped to develop my ears.”

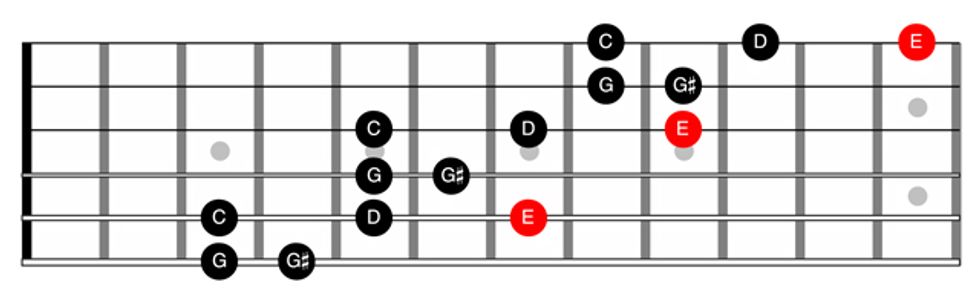

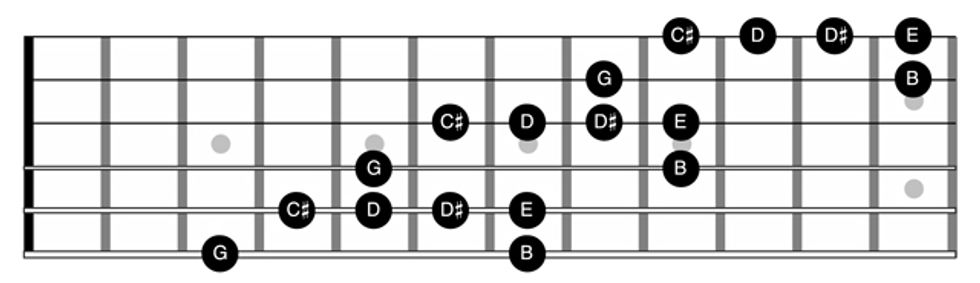

Over A7, rather than just reaching for a predictable A7 arpeggio, Gilbert suggests trying a shape that leaves out the root but adds the 9th (B) and the #4th (D#), in addition to the 3rd (C#), 5th (E), and b7th (G).

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)