With all the tone-chasing we guitarists do today, you hear a lot of talk about how certain things are going to make some magical difference in our sound. We’ll argue endlessly about whether class-A amps, new-old-stock tubes, germanium transistors, and countless other minutiae are superior to their alternatives. But rarely do you hear us talk about getting that perfect sound by purposely ravaging the structural integrity of our gear. Perhaps that’s a shame—because when former Kinks lead guitarist Dave Davies turned visceral in his tone pursuits back in 1964 while recording the band’s seminal hit “You Really Got Me,” he single-handedly changed the sound of rock ’n’ roll forever.

“I always wanted to write a song about that period in my life and what was going on,” Davies recently told Premier Guitar. And with “Little Green Amp,” the lead single from his new solo album, I Will Be Me, he did just that. Back when Davies and fellow Kinks—older brother Ray (vocals and rhythm guitar), bassist Pete Quaife, and drummer Mick Avory—were recording their eponymous debut, Dave couldn’t get a sound that he liked out of his tiny green Elpico amp. It was either too bassy or too bright, but never right. So he decided to slash the speaker with a Gillette razor blade. The result was a raw, ragged, primal distortion that went down in history forever. “In all modesty,” says Dave, “I think that sound changed an awful lot of people’s values and ideas about guitar playing, and music in general.”

It’s a bold claim, but it really is no exaggeration. Dave Davies is the guy who introduced the glorious mayhem of the distorted power chord to the guitar vernacular. Popular music has never been the same since. Artists as disparate as the Ramones, Van Halen, Metallica, Green Day, and, well virtually anyone who’s hit a power chord owes a debt to Dave.

“You Really Got Me” hit No. 1 on the U.K. charts and put the Kinks on the map the same magical year that saw the Beatles heralding the British Invasion with their legendary appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. It seemed the Kinks were poised to follow suit as the next British superstars, but the band had a reputation for violent in-fighting—incidents like Avory sending Dave to the hospital after flinging a cymbal at his head, and Ray getting into a scuffle with a union member during a 1965 American tour were the norm. These incidents and other missteps got the Kinks banned from performing in the States for four years—well past the peak of the Invasion. Nevertheless, Dave and the Kinks made their mark as an iconic band with hits like “Waterloo Sunset,” “Lola,” “All Day and All of the Night,” and “Come Dancing.”

But the Kinks’ legacy has long been marred by acrimony between Dave, the extrovert, and Ray, the more introspective one. They were the last of eight children, and they’ve had a career-long feud that went beyond simple sibling rivalry. The sheer animosity between the two is at a level that makes Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth seem like best friends. While the tension made for many incredible moments onstage, the band disbanded in 1996 and never looked back. To this day, it seems the war may never end. Even after bassist and founding member Pete Quaife passed away in 2010, Dave refused Ray’s proposal to play at the funeral.

That’s not to say Dave is musically inactive. In addition to the recent creative surge that sparked I Will Be Me, he has released several solo albums since 1980. And with its impressive assemblage of guests—including Anti-Flag, the Jayhawks, and Geri X, among others—Dave’s latest effort showcases a broad range of stylistic influences that go way beyond just three power chords.

We recently caught up with Dave, who was fresh off his stint at New York City’s City Winery, to discuss I Will Be Me, get new perspectives on that ravaged little amp, and see what it would take to get him to reunite with Ray.

What ignited this period of creativity that culminated with I Will Be Me?

Lots of things—everything from the economic situation of the world to the political situation across the board to my first grandson being born. And I was happy with the songs I was writing. I felt like I was in a good space in my head with the songs, and that’s always a good place to start. I felt motivated to write. Once I got one song together, the other ones kind of crept out. The first one I wrote was “Living in the Past”—that kick-started the writing.

What’s that one about?

It’s basically about a character who’s confronted with the world falling apart. He kind of tends to look back but he can’t ignore the future. He’s reminded on a daily basis that the future is here to stay. When we get confronted with strange world conditions we tend to try and stick our heads in the sand sometimes.

The intro sounds a bit like “Sunshine of Your Love.”

I don’t know. Everything sounds like something. What I wanted to do was make it like a Kinks riff—like something I would do on a Kinks record. [Sings “Sunshine of Your Love” riff.] Cream was really inspired by “You Really Got Me”—they copied the riff.

So they owe you for that.

They owe me something, I think [laughs].

Congratulations on becoming a grandfather. Is that what inspired “The Healing Boy”?

Yes, it’s about him. It changes the way you feel about the world and injects more optimisim into your life.

That song starts off with an eclectic, almost classical vibe, and then veers off into something of a country-folk style when the vocals enter.

Yeah, I like a lot of classical music. I like to cross-pollinate with classical, techno, rock, and all sorts of things when the mood is right.

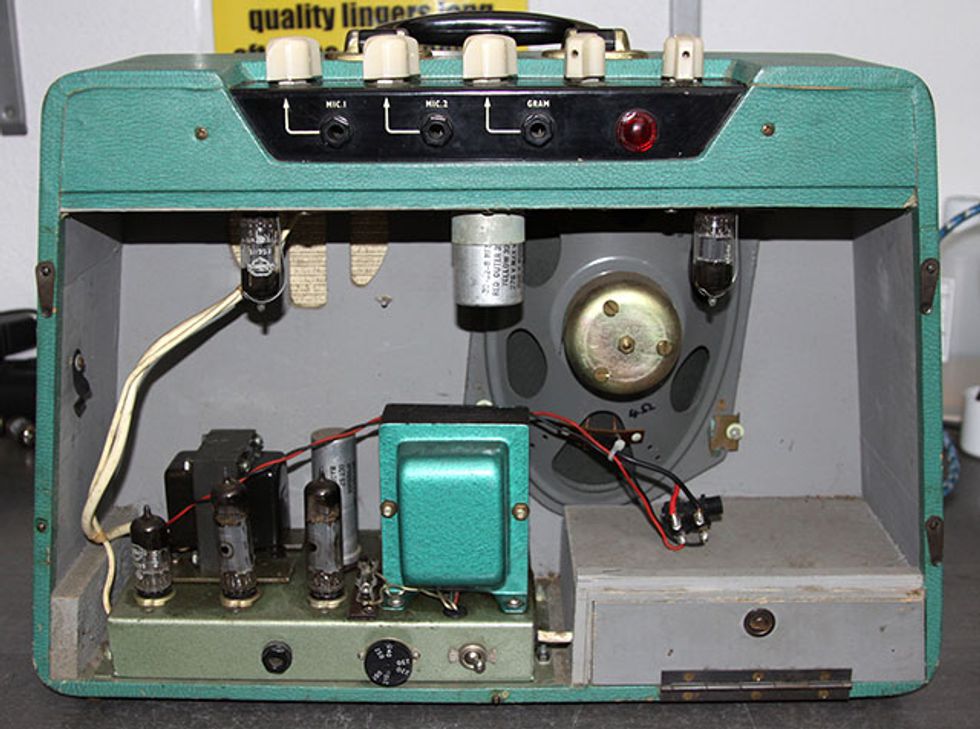

According to amp repairman Russ

Fletcher, the Elpico AC-55 was first made by the British company Lee

Products around 1956, and it was intended to amplify tape recorders and

record players—hence the "Gram" (gramophone) input jack. It put out 10

watts and used six tubes—an EZ80 rectifier, two EL84 power tubes, and an

ECC81 PI and two ECC81s in the preamp. “I've seen one or two with

ECC83s/12AX7s instead of the ECC81s,” says Fletcher. Reportedly, the

fuzz-guitar sound on the Beatles’ "Tax Man" was Paul McCartney playing

through an Elpico.

While recording the Kinks’ debut album in

1964, Dave Davies altered the course of guitar history with the help of

an Elpico AC-55 amp like this one. Unhappy with the sounds he was

getting from it, he slashed his Elpico’s speaker with a razor blade and

inadvertently created one of the rawest sounds in early rock, as heard

on the classic “You Really Got Me.” Photos courtesy of Russ Fletcher

(russhifi.blogspot.com)

“Little Green Amp” refers to the amp that changed rock ’n’ roll

forever. Throughout the song, you also make spoken references to

historically significant songs like Bobby Darin’s “Splish Splash” and

Gershwin’s “Summertime.” Is there some sort of common thread?

It’s mainly autobiographical, but I tried to make it humorous. There was a record I used to love as a kid—Bobby Darin. [Sings] “Splish, splash, I was taking a bath,” and then [sings]

“Summertime, and the livin’ is easy.” I was just having a bit of fun.

There’s also a reference to the Kinks’ “Sunny Afternoon.” [Sings] “In the summertime….”

The “Little Green Amp” riff sounds like the “You Really Got Me” riff played backwards.

It is exactly that riff backwards.

Did you use the little green amp on that track?

No, I used a little old Peavey Decade—a solid-state amp.

Did you slice its speaker with a razor blade?

No. I just cranked it and used a cheap mic.

What sorts of reactions did you get to that sound back when “You Really Got Me” first came out?

People either loved it or hated it. Some were, like, “What the [expletive] is that shit?” Other people would say, “Wow!” It was mixed feelings, but once the record started to chart and do well, people really took to it. It was quite a revolutionary step, really, in regards to modern music. There was nothing like it. They didn’t have heavy metal or hard rock back then—it was unheard of.

There’s some controversy about who played the solo on that song.

Oh, come on! It’s me that played it—it couldn’t be anybody else. The way that I played that solo, no one on this planet could play it like me. That’s ridiculous.

How did you replicate the “You Really Got Me” sound after that? There weren’t as many amp options back then. Did you go around slashing more speakers?

No, no. After that, in the early ’70s, amplifier manufacturers developed pre-gain. So, in a way, I should have patented it and called it pre-gain. I already knew what it was—basically cranking up and overdriving one amp to boost the input of another amp. It gave a lot of people different notions about amplification. We found that, in that time, people were making amps that had pre-gain and post-gain. Mesa/Boogie—when I heard their amps, I thought they perfected it to a really great degree. I still use Mesa/Boogie amps. They’re great. I love their tone and the way you can really push the pre-gain. It’s not the same, but in principle it’s similar.

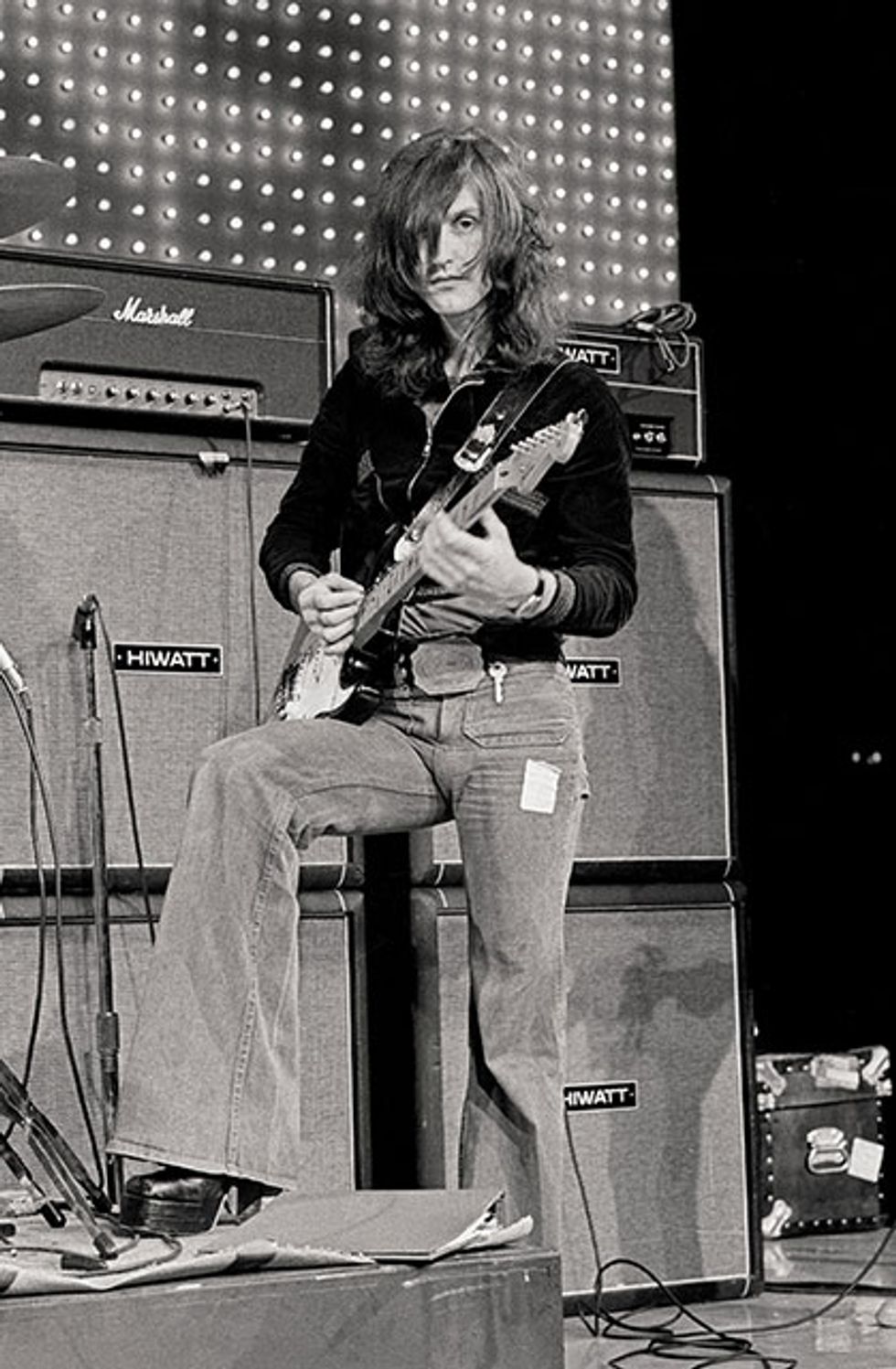

Dave Davies pays tribute to the “Little Green Amp” that changed rock ’n’ roll forever at a recent engagement at New York City’s City Winery.

When you played “Little Green Amp” at your recent City Winery gig, your solo differed from the album version. Do you like to improvise solos live?

Yeah, I can only improvise. I only have a little block where I’m supposed to do it, so I just do it for fun. If you keep playing the same old thing all the time, that drives you insane.

But it also increases the risk of something going wrong, doesn’t it?

That’s the whole magic of live music—that’s why we like it.

Davies playing a Strat live with the Kinks in 1974, photo by Greg Papazian

How did you feel about Van Halen’s cover of “You Really Got Me” when it came out

It’s okay. I love it when people copy what I do and what the Kinks do. The Kinks’ recording of “You Really Got Me” sounds like anxious kids who are struggling—like kids fighting the world. The Van Halen version sounds too accomplished—it says, “We know what we’re doing.” It’s still good, but the attitude is totally different.

Would you ever reciprocate and cover a Van Halen song?

Not really—but I like their music. It's good to have different types of music and guitar sounds. The joy of music is the variety. That’s why I like to write about different things using different styles.

Looking back today, how would you describe your contributions to electric guitar?

Oh, I don’t know. I have no idea. I mean, where would any of us be without Les Paul? Where would any of us be without Big Bill Broonzy? Or Muddy Waters? Or John Lee Hooker? Or Chuck Berry, for Christ’s sake? All these things go inside you and you want to emulate or copy them all. I love that. Chuck Berry was one of the biggest influences for me. And rock people from the ’50s and ’60s. And then Les Paul changed the whole idea of recording.

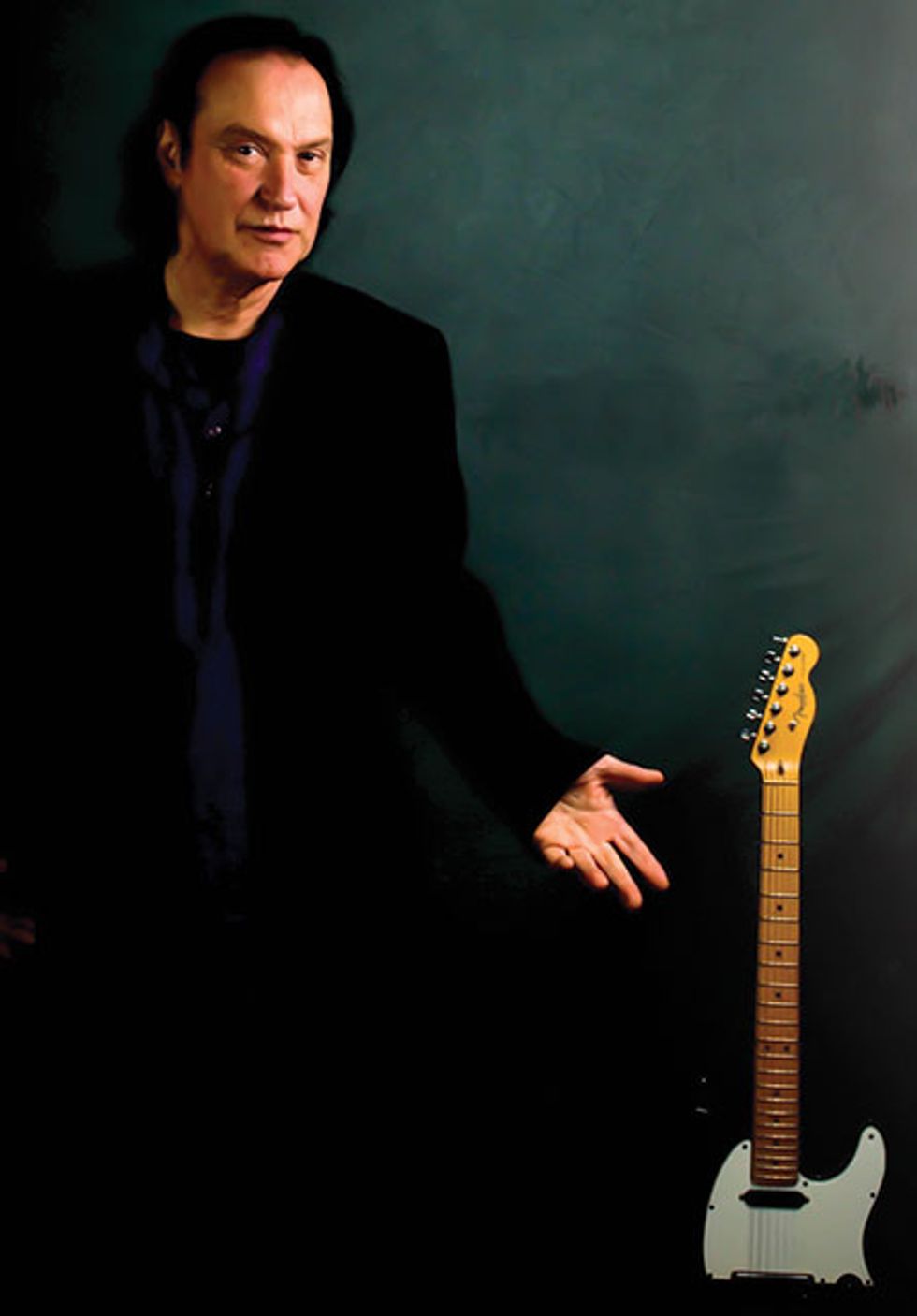

Let’s talk gear. What’s your main axe now?

It’s a Fender Tele with a maple neck and Lace Sensor pickups that lean toward the Gibson mode of pickups.

On the original recording of “You Really Got Me,” you used a semi-hollow Harmony guitar. Can your Tele get you in that ballpark?

No, not really. But it’s just a more modern version of it. It’s similar. The original guitar I used was a semi-acoustic Harmony Meteor with DeArmond pickups.

This is where it all began. Armed with a Harmony Meteor semi-hollowbody, Dave Davies (far right) hams it up in this classic live footage of the Kinks playing “You Really Got Me”—the song that changed rock ’n’ roll—and guitar playing—forever.

You previously used a Gibson Flying V. What took you away from that?

It’s difficult to play [laughs]. And the weight is all wrong—the neck and the machine end. It’s a fancy guitar to look at—it’s really a piece of visual art.

Earlier you mentioned you’re using Mesa/Boogie amps—which model?

A Dual Rectifier.

That’s slightly surprising, given that it’s such an iconic heavy metal amp.

Yeah, but I like it. You can mess around with it—don’t just plug it in and switch on the heavy-metal button [laughs].

Why did you use the Peavey Decade instead of the Dual Rectifier on “Little Green Amp”?

Because I’ve found that when you record, little amps sometimes have more impact. In the studio, you might only need that compressed, tight sound. People don’t know that it’s not a thousand -watt amp when they hear it, if it sounds right. Big amps are good for when you’re playing a big place.

Given that you and Ray are still healthy and making music, what do you think it would take for the remaining members of the Kinks to get back together?

I have no idea. [Maybe] if Ray just had a bit more grace about my value in the history of the Kinks. I mean, he’s always undervalued my input. That’s why I had to make this album. Because, y’know, I will be me—I am a person with ideas, energy, and a spiritual path. It’s emotional and we have to start nurturing and encouraging people around us to help us, not just take the good bit. We’re all in this together—it’s the same, politically and globally. We shouldn’t try and isolate ourselves from other people. We need to learn to integrate ourselves with humanity.

You have a great spirit.

A lot of that spirit grew out through listening to people like Huddie Ledbetter [Lead Belly] and Hank Williams and all these great musicians. The spirit has always been there—rock music has always been a force for the good, I think. We abused it to meet our own agenda for greed and big business, but at the heart of it, rock ’n’ roll has always had a true and pure spirit.

The Kinks’ “All Day and All of the Night” spearheaded the three-chord rock genre. The screams that emanate from the crowd in this classic clip from 1965 make it clear that a revolution was in the making.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)