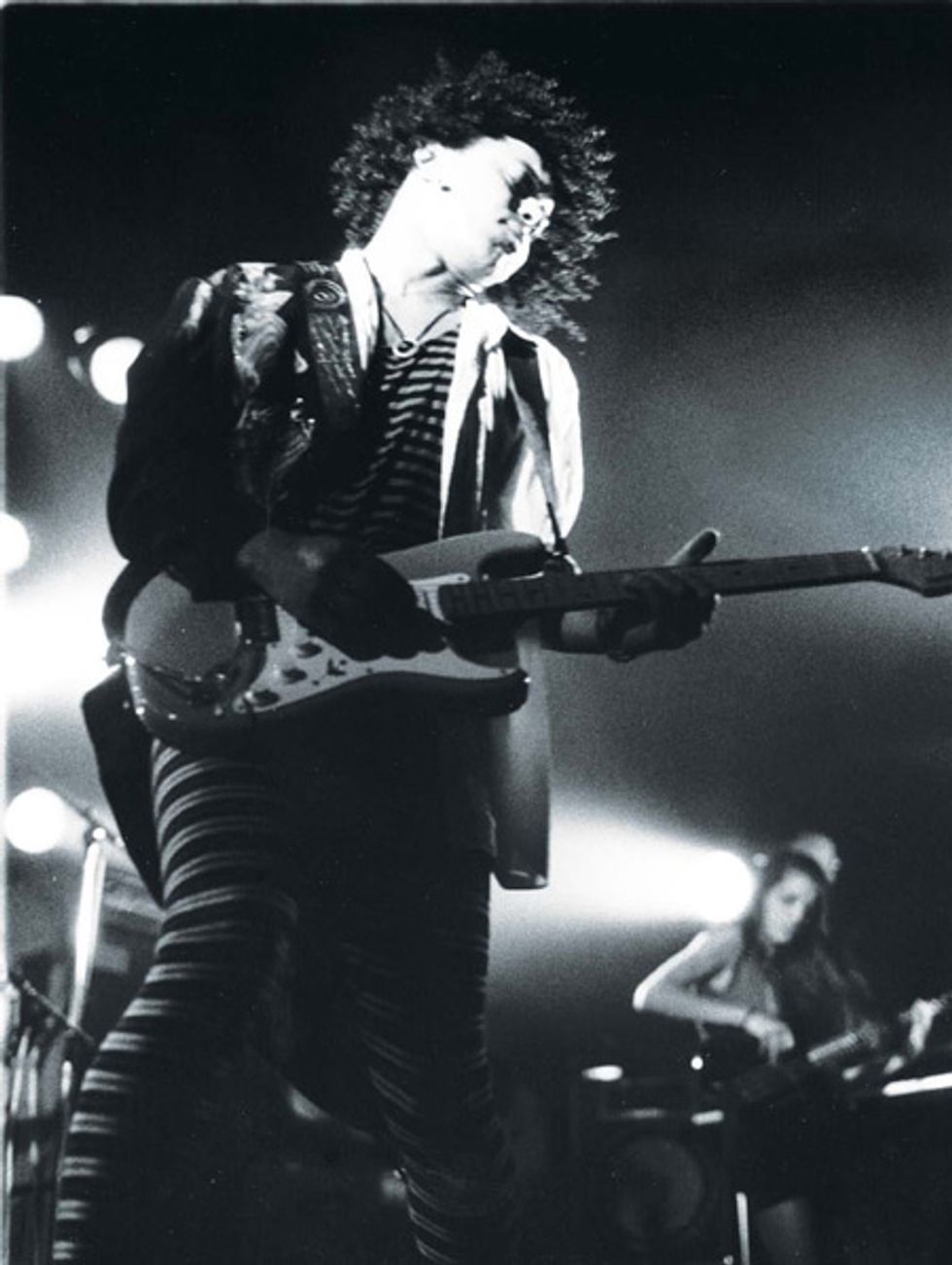

Ivan Julian at a 1990 gig with Richard Hell at Club Citta in Kawasaki, Japan. Regarding the

pants, Julian says “Jet lag makes you do weird things—but it’s fun!” Photo by Gin Saton

| Listen to Julian's "Sticky" and "A Young Man's Money" from The Naked Flame: |

As wide-ranging as his work has been, it wasn’t until recently that Julian released his first solo album, The Naked Flame. And he says he wouldn’t have even done so if it weren’t for the members of an Argentinean band called Capsula insisting upon it while he was mixing their 2009 album, Rising Mountains. Fittingly, Capsula joins Julian on his long-overdue solo debut. The music is raw and cathartic and filled with all sorts of fascinatingly multifaceted guitar parts—from the explosive leads of the title track to the funky minor-7th rhythm work on “The Funky Beat in Siamese” to the country-blues inspired octaves of “You Is Dead.” We talked with Julian about how he got these sounds and, more broadly, how he conceives music in general.

I understand you have the distinction of possibly being one of the only guitarists alive who first played the bassoon.

|

You also absorbed a bit of theory in high school. Did that shape your approach to the guitar?

It’s more like an analytical thing: I know my scales and my intervals, and I can easily communicate with other musicians. I don’t really think about theory when I play guitar, as you can probably tell from my playing. [Laughs.] To me, it’s more about geometry than anything else—I make triangles, squares, and trapezoids on the fretboard with my fingers and see what happens.

What was it like to make geometric shapes with Richard Hell & the Voidoids as part of the first wave of punk?

It was always interesting [laughs]. Richard Hell got a lot of criticism back in the day for his lack of prowess on bass, but I always defended him. While he wasn’t technically accomplished, he was always coming from a place far from the mundane. He invented these great bass lines that almost sounded illustrated— like cartoon characters—and Bob [Quine] and I would try to fit something around those lines. On the other hand, it could sometimes drive us crazy to work with Richard. Because he wasn’t a “real” bass player, we could spend up to a month rehearsing a song in order for him to get up to speed.

How did you and Quine distribute the guitar responsibilities?

Bob and I agreed we’d never play on the same part of the neck at the same time. I’ve always found that it’s redundant for two guitarists to be playing the same open G chord. One should find something different to play, to make things interesting, and both guitarists needn’t be constantly playing at the same time. Another thing about working with Bob was that he was heavily jazz influenced, and he turned me on to a lot of great music like Albert Ayler records and odd Charlie Parker outtakes—nonstandard stuff that got me to incorporate subtle nuances when soloing and encouraged me to be more adventurous in general.

Julian playing an Ampeg Dan Armstrong guitar at New York City’s famed CBGB club in in 1978.

“That’s the last guitar I ever sold,” he laments. “I miss it. Never sell guitars—ever.” Photo by Tanda

How would you describe your compositional process?

The impetus for my songs often comes from my immediate surroundings. I wrote the music to “Liars Beware” off [the Voidoids’ 1977 classic] Blank Generation when I had just moved to New York and heard about four or five sirens upon exiting the subway—sounds that turned themselves into a guitar riff. Other times, a song will emerge as a reimagining of an older one. When I wrote the title track to The Naked Flame, I set out to make a modern-day version of “Fire” by Jimi Hendrix. My writing process also involves the other musicians I work with—their input can take a song to a place I hadn’t envisioned.

On The Naked Flame you cover Lucinda Williams’ “Broken Butterflies.” How did your arrangement come about?

I was a slave to the song—I gave it what it needed to walk on its own two feet. The song seemed to call for just a tiny bit of guitar and mostly harmonium, on account of its organic sound. I love that instrument. It’s just so human, with its leather bag pumping away like a pair of lungs or some wild sexual thing. By the way, I didn’t actually play the guitar on that track. It’s my friend Nick Tremulis, a player from Chicago who’s got this wonderful, rootsy style. I told him just to pretend to be me, so his playing on the song is an interpretation of what I do—which is often over-the-top and angular. What you hear isn’t in the exact same sequence as he played it, though. This is a rare example of my using a little Pro Tools action to move the guitar parts around a little for a more powerful arrangement.

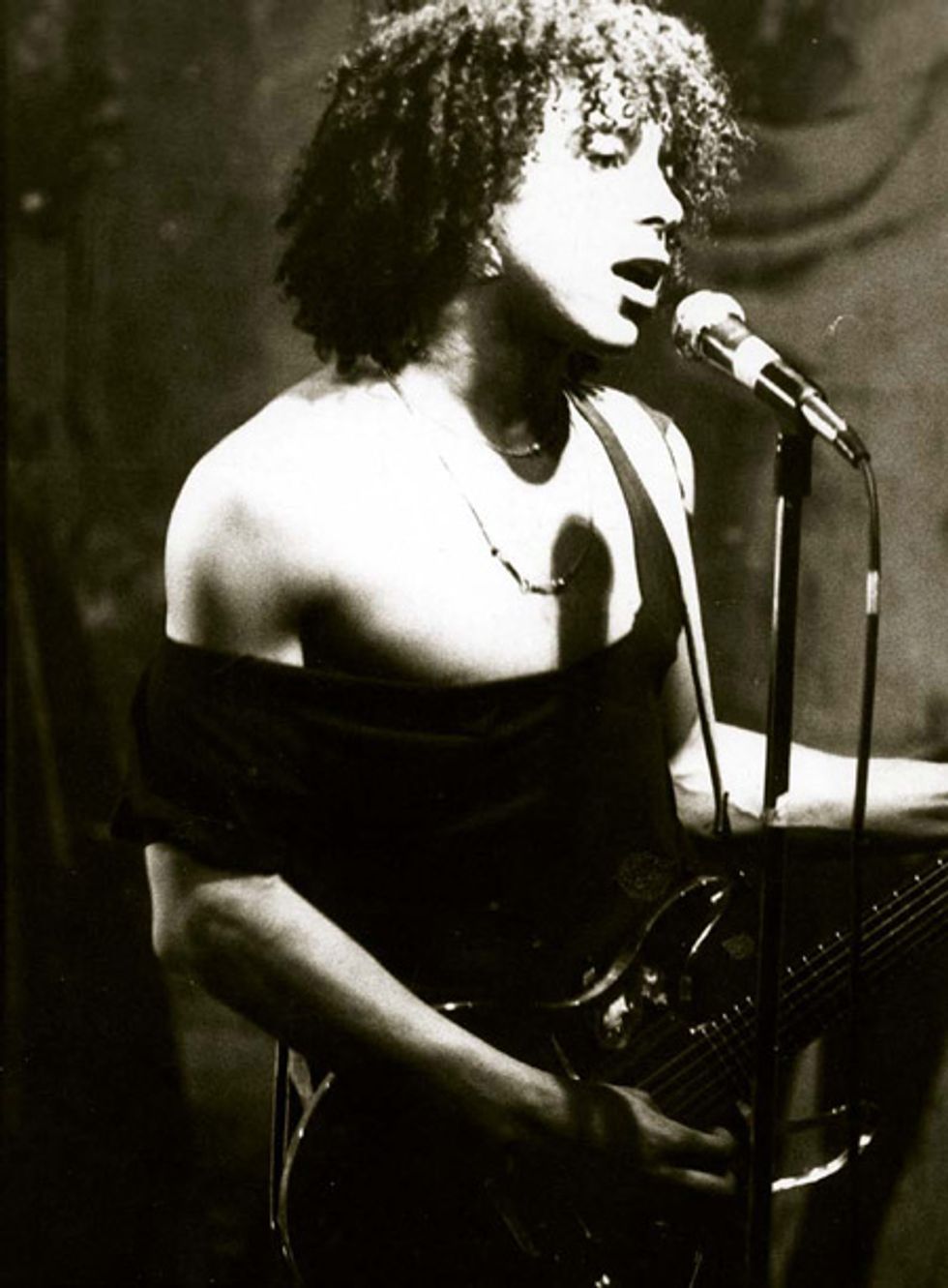

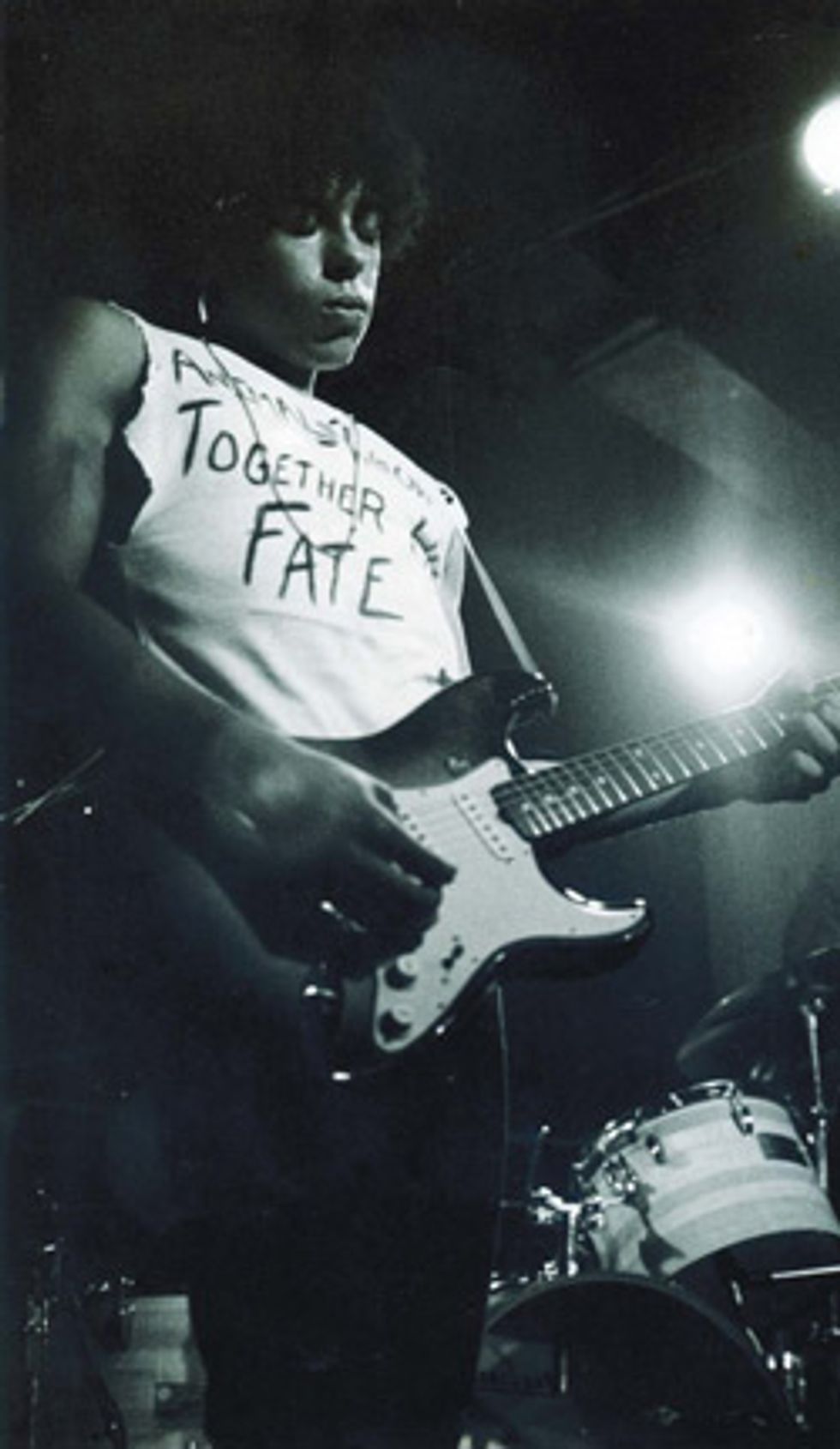

Julian playing a 1966 Fender Mustang at a 1981 gig with the Outsets, the

band he formed after leaving the Voidoids. Photo by Lisa Lloyd

Let’s talk about some of the guitar work you did play. How did you get that great, vocal-like sound on the title track?

In my living room, I plugged my Strat into a Peavey Bandit and cranked both the amp and a Rat pedal just before the point of breaking up. I mic’d the amp with my favorite mic for electric guitars—an Electro-Voice PL76, which has such a warm, natural sound. I placed the PL76 off-center and got a bit of the room sound in there—the room should always be a part of the amp, in my opinion. To record the parts I used an old Tascam 8-track, which I fed into a 24-track for a raw sound that you don’t get when using digital equipment exclusively. As for the actual playing, I made a conscious effort to avoid the obvious—tired blues lines between the vocal phrases—so I tried to create some unusual nuances there.

Watch the video for the title track from The Naked Flame:

Your backing band on The Naked Flame, Capsula, is especially hot. How did this collaboration come about?

Capsula is this Argentinean band based in Spain. I mixed their album Rising Mountains at my studio, and they kept prompting me to make a new record. Finally I gave in and sent them demos of some new songs for them to play around with. They rerecorded the songs and gave them this urgent treatment that let me know they really got me and we were on the same page. I had to do the record after that.

Julian and Capsula bassist Coni Duchess (playing a Gibson Grabber) at a 2009 gig in Spain. Photo by Berlén

Did you write out their parts or did they learn them by ear?

Generally, I don’t write out music unless I’m working with string or horn players, so it was all by ear. I’m sure it was a pain in the ass for everyone to learn—the music is much more complex than it sounds—but they nailed it. The band was on fire.

Let’s talk gear. Which guitars do you prefer?

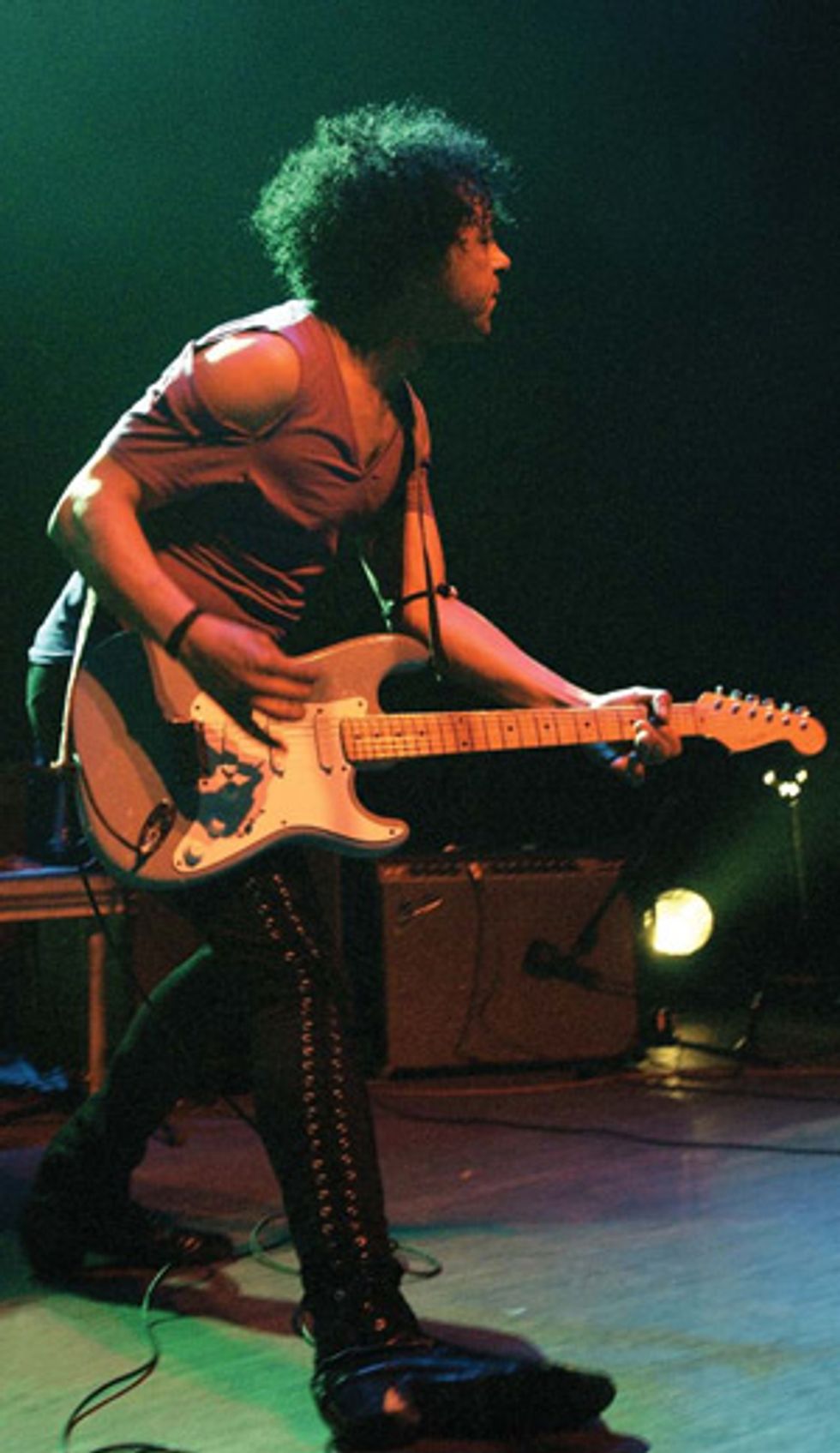

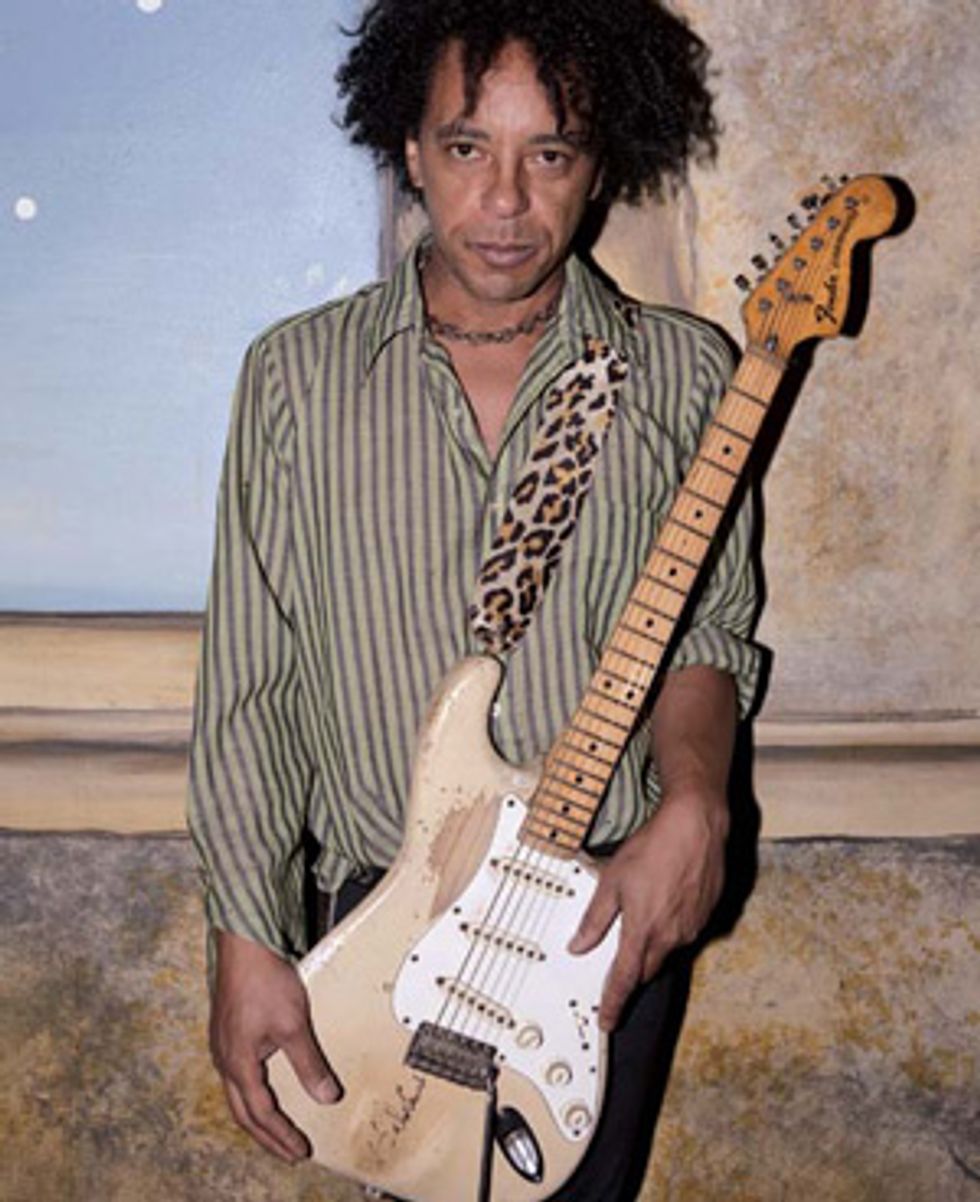

Julian with his 1962 Strat (which has an epoxied-on 1973 neck) at Europa Club in New York City in 2007. Photo by Jackie Roman |

I’ve also been enjoying these new electric guitars made by Hanson. I’ve got a solidbody one called the Cigno, which has P-90-style pickups and sounds great. As for acoustic, around ’92 or ’93 I visited Gibson’s acoustic factory in Bozeman, Montana, and smelled the wood and glue of a new Hummingbird, played it, and lost my mind. I decided to buy it on the spot no matter how much it cost, and it’s been my main acoustic ever since.

Are you picky about strings?

I use D’Addarios—.010s at home but .011s or .012s on the road if I’m feeling like a real man. I find that I get a bigger and better sound with heavy strings higher off the fretboard. Something else I do, which I picked up from Nile Rodgers, is put acoustic strings on an electric guitar. The magnets don’t pull on the metal as much as they do with electric strings, so you get a much woodier sound—a cool thing for chords and rhythm stuff. Currently, I have acoustic strings on the 12-string Tele. I wouldn’t recommend that readers put acoustic strings on all their electric guitars, but try it on at least one sometime—you’ll be pleased with the sonic results.

Julian and his 1962 Strat with drummer Florent Barbier and bassist Sharron Sulami at a

May 2010 gig at the Trash Bar in New York City. Photo by Ann ‘Arbor

How about amplification and effects?

One of the key ingredients to my sound is the speakers I use—Electro-Voice SROs, which I put in everything, even that Peavey Bandit I’ve got. Generally, I use a silverface Fender Twin live, but in the studio I use only small amps, which are best for recording since they push less air and get more tone than larger amps. I’ve got everything from old Danelectros to Magnatones to a nice blackface Fender Princeton.

I don’t use much in the way of effects, just a Rat distortion and Boss compression and digital delay pedals. I’ve also got an old Maestro Mini-Phase, which I used as an envelope filter on “The Funky Beat in Siamese” from the new record. I should mention that I played a Danelectro baritone guitar on that song, which was fun but tricky—you have to use a whole different approach than if you were just playing guitar or bass.

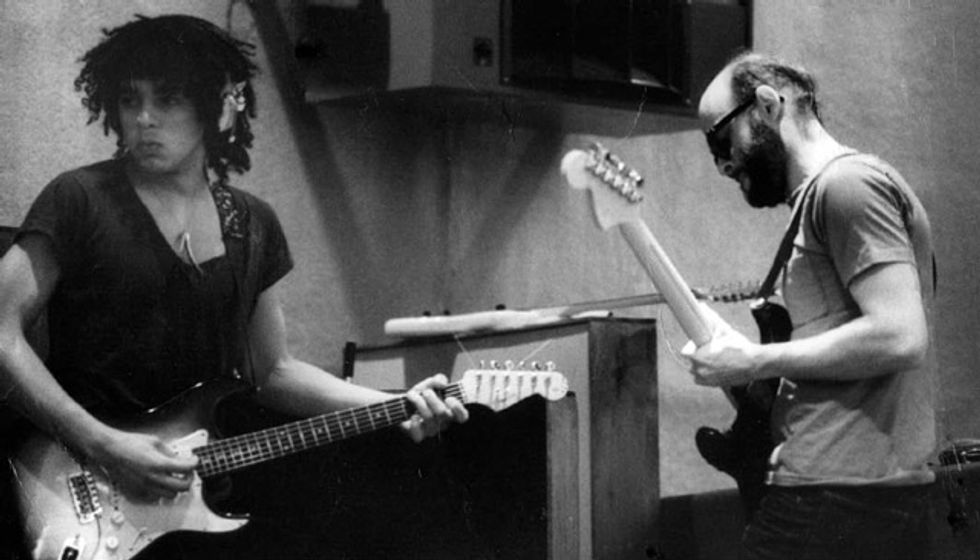

Julian and Bob Quine recording “Walking on the Water,” from the Voidoids 1977 album,

Blank Generation. Photo by Kate Simon

How would you describe that approach?

On the baritone, it’s best to come up with lines and patterns that fall in the middle of the instrument’s range. If you play in the bottom of the range, you’ll get in the way of the bass guitar, and if you play high on the neck, you might as well be playing a guitar. It’s as if you’re in an orchestra playing a cello, whose range overlaps with the standup bass and the violin.

Speaking of how things blend together on tracks, how did you get into recording and engineering—and do you have a benchmark for that work?

|

What’s an example of an odd request that another producer might reject but that you’d accept?

When I work with Jon Spencer, he might ask for something so compressed that it’s all static-y and fucked-up sounding— sounds that most people try to avoid. Or he might want an odd percussive sound and I’ll help him find it, for example, by banging on the edge of a Wurlitzer with a drumstick.

How would you sum up your overall philosophy when it comes to writing, playing, and producing?

I say no matter what you do, let your spleen show—give it your all.

Ivan Julian’s Gearbox

Guitars

1962 Fender Stratocaster with 1973 neck, assorted vintage Teiscos, Danelectro electric baritone, Hanson Cigno, Gibson Hummingbird

Amps

1970s Fender Twin Reverb, 1960s Fender Princeton, Peavey Bandit, assorted Danelectros and Magnatones

Effects

Pro Co Rat, Boss CS-3 Compression Sustainer, Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

D’Addario XLs (.010, .011, and .012 sets), D’Addario Phosphor Bronze (.012s for 6- and 12-string guitars), Fender medium picks, Kyser capos

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)