Make no mistake. Johnny Marr is one of the defining guitarists of the 1980s. A true master of melody and economy, the former Smiths guitarist’s stylish and understated—though never uninspired—playing has earned him a top spot on the short list of the most influential and singular musicians of his generation. However, there’s far more to Marr’s oeuvre than just the contributions he made as the key sonic architect of those cultishly beloved Smiths records.

Over the 31 years since the Smiths’ demise, the Mancunian guitar hero’s immediately recognizable playing has popped up in seemingly infinite and varied places, including substantial appearances on albums by the Talking Heads and Oasis, a tour with the Pretenders, and long-term stints as a member of English post-punk mavericks the The and American indie-rockers Modest Mouse. In recent years, Marr has even found himself scoring major Hollywood films like Inception and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 alongside industry titan Hans Zimmer. Amid all of it, the ever-restless Marr has somehow found the time to continue the process of redefining himself as a solo artist, and has just released his third solo LP, Call the Comet.

On the new album, Marr appears a confident and charismatic frontman and songwriter. He’s never been one to deny his muse a trip to unexpected territory, and the album draws from a wide swath of the many facets that have developed within Marr’s musical world over the years, ranging from the jangling melodic pop he’s best known for to glam-rock barnstormers, electronic groovers, and a litany of other styles. Despite the eclectic nature of its songs, Call the Comet is a remarkably cohesive record that’s brilliantly laced together by the man’s incomparable pop sensibilities. His love affair with the guitar remains the true life force of the album. So much so that Call the Comet could serve well as a manifesto of sorts for Marr’s guitar work. Rendered with chiming 12 strings, capo-choked altered tunings, and his hallmark ability to pen impossibly catchy guitar hooks, Call the Comet was tracked using many of the iconic vintage instruments fans will recognize from throughout Marr’s career, including quite a few purchased directly from the Who’s late bassist and avid guitar collector, John Entwistle.

PG was graciously granted an opportunity to pick the mind of the disarmingly friendly icon during a break while on tour. The passion Marr still harbors for the instrument is downright palpable, and the ensuing chat found us deep in the details of his fantastic new album, and yielded pearls of wisdom on everything from the man’s general guitar philosophy, approach to collaboration, his late-career love affair with the Fender Jaguar, and yes—the Smiths.

Having lived so many different lives as a guitarist and songwriter, you remain not only wildly prolific, but focused on creating new things rather than subsiding on your legacy. Could you pinpoint what keeps you so inspired as a guitarist after all these years?

The thing that keeps me excited about it is the thing that always excited me about it! Some of that is mysterious and I’m not entirely able to analyze it, which I’m happy about and like that I can’t really figure it out. I’ve just always honored my enthusiasm and love for the guitar and I’ve never let myself get a jaded attitude or really lost my original love for the thing that it does.

There are some things I can analyze objectively about the guitar—one of which is that I think it’s an incredible machine for making pop and rock music on. That was something I identified as a teenager and that’s never really left me. I know that guitars do a thing that literally only guitars can do—harmonically, sonically, etc. On a record, I like killer Moog sounds and interesting synth sounds or what a good piano can do, and really all the aspects of certain kinds of records, but I go out of my way to try and put some parts down and really make them work on the guitar, like, it’s my duty, really.

It’s been very interesting to see how well your playing style works in different contexts over the years. How would you say your identity as a player has evolved—especially with the varied projects you’ve taken on?

Thank you for saying so. If my identity has changed, it’s only changed to the outside world. In my own mind, I’ve never had any restrictions as to what I could or would do. I’ve always wanted to explore everything on the guitar, perhaps with the exception of certain very particular styles. For example, growing up when I did, blues-rock was already kind of done, so that was something I went out of my way to avoid. The same with stuff like shredding. I’m not judgmental about anything, to each their own, but it can be good to know what you don’t want to do. But really everything else was fair game. Like back in the old days, I couldn’t wait to turn the tape around backwards and do reverse guitar stuff on Smiths records. Any technique that served the kind of music that I wanted to make was always fair game.

I think, and hope, variation has come into people’s idea of me now, which is to say I’m not only about “This Charming Man” or jangling away on a Rickenbacker.

Johnny Marr says his third solo album, Call the Comet, is “mostly concerned with the idea of an alternative society.” It was recorded with Marr’s band at the Crazy Face Factory in his hometown of Manchester, England.

Your style is immediately recognizable. Do you have any advice for players looking to forge an identity in an age where it both feels like it’s all been done, yet new tech and the number of possibilities it presents can be overwhelming?

The amount of possibilities is an interesting point to raise, because in today’s culture, there really is option fatigue. The digital revolution across all the arts has made it so simple now to go down any road, and we all know how easy it is to pull down the plug-in and you’ve immediately gone from having a ’60s keyboard sound to a full orchestra, and that can often mess with the identity and direction of music. It’s not always the best thing to be able to have literally everything at your fingertips.

I come from a school of thinking where it’s very important for a musician to have their own style—regardless of whether they were famous or not. It was part of learning and developing as a player to have your own thing. Sure, you have to learn from your heroes and different sources, but it was almost a given that your endgame was to try and be as much of an individual as possible. I do believe that if it’s on someone’s agenda to have their own sound and style, that awareness and intention is really important and will carry you through. I think it’s terribly important to at least want to have your own individual style.

That said, you do have to learn from somebody and it’s great to be inspired. I was inspired by all kinds of different players and records. The organ on Mott the Hoople’s All the Young Dudes was a really big thing for me harmonically. Some of the backing vocals on the T. Rex records, too. I’ve done things like put a slide guitar through a wah-wah and harmonized it purely to get the same effect as Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan [aka Flo & Eddie] who sang on Marc Bolan’s records. They had this very feline backing vocal sound that you hear on things like “Get It On” and “Metal Guru,” and I’ve often done that on tracks. I think whatever you’re influenced by is fine as long as you’re passionate about it and you have the intention of being unique.

Why does Johnny prefer Jaguars? “When I’ve played with other guitarists, my guitar tends to sit just a bit above everyone else’s Les Pauls and even Strats, and that kind of suits me well,” Marr shares. Photo by Lindsey Best

“Hey Angel” is a very T. Rex-esque track and has some very muscular, distorted guitar sounds that are a departure from those most would associate with you. Could you tell me how you copped the tones on that one?

I was definitely a child of glam and it’s been on quite a lot of things that I’ve done over the years, and I’m happy that that came through there! The main rhythm guitar on there is a 1973 Les Paul Custom, like the one James Williamson used in the Stooges. That guitar was running through a Fender Bassman cranked up very hot. The solo and lead parts were done with the Carl Martin PlexiTone pedal, which is a great-sounding thing!

On that track, I didn’t layer the guitar because sometimes when you track a thick barre-chord rhythm part, you can make it sound more conventional or too polished if you’re not careful, which can go against your intention to make it heavier. A good example is what Mick Ronson used to do with Bowie when he would try to ape Jeff Beck’s 1960s Yardbirds style, and I’ve often intentionally left just one raw, in-your-face Gibson sound on a track in that style. “I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish” off the last Smiths record comes to mind.

Are you still using the Boss GT-100 multi-effects processor live, and can you explain why you’ve stuck with that unit for so long when the industry has experienced such quantum leaps in modeling tech over the years?

I use that live and for a very, very simple reason: I need to be able to scroll up and down through patches without having to look at my feet. Those Roland/Boss multi-effects have a control input that allows me to scroll patches the way I like without breaking my concentration on being in the moment with an audience. I found when I toured in the early 2000s with the Healers and had a more conventional board that I had to either make the decision to have less patches available—which I didn’t want to do because it meant standard delay times, overdrives, lead sounds, etc., and I had to be looking down between verses and solos—or doing it the way I do it with the GT-100, which is have a single up/down pedal at my mic stand and learn the combinations up and down through the patches that I need to do, which is easy. It’s so much more about simply honoring being a singer and a frontman.

I have to say that I defy anyone to be able to tell the difference live between the GT-100 and my boutique effects board sonically. When I program it, I’m pretty nerdy about it and I get in pretty deep with the tonal modification. Otherwise I wouldn’t do it. I might be going to a different system sometime next year, but I also didn’t want to take someone with me on the road just to go up and down through my patches. I’m not playing stadiums yet!

On the flipside of that, could you tell us about the gear that inspired you or made important appearances on the new album?

I used the amps that I’ve had and used forever: a 1965 Fender Deluxe Reverb, which is my main amp, and a blackface 1960s Fender Twin Reverb that I’ve used on almost every record I’ve done. A lot of guitar sounds on the album came from an old HH Musician transistor amplifier, which all the British new wave bands used in the late 1970s and sounds crazy good. I also used my old tweed Bassman from the ’50s.

Pedal-wise, the Lovetone pedals that I got in the ’90s still sound really good to me, and I used the Brown Source overdrive and the Doppelganger on a really slow setting, so it’s very subtle and gives the sound a sort of trippy modulation. One of the really old MXR flangers from the late ’70s was on the album a fair bit. I also like the Carl Martin AC-Tone, which is really good, and the Carl Martin reverb is excellent. I always use a Diamond Compressor with my Jaguar; they’re sort of made to be with each other in my experience. I also use a subtle modulator pedal called Mr. Vibromatic, by SIB! Electronics, and I really like the new Electro-Harmonix MEL9 Mellotron pedal. For some backwards sounds, I use the old green Line 6 DL4 delay—there’s something about the creaminess of the sound and the lack of artificial top end on those things. They’re kind of the best real-time backwards sound I’ve heard so far. I only use them for that particular sound. A good crunch sound I get on the song “Rise” is the Menatone King of the Britains, which I love.

Guitars

Fender Johnny Marr Signature Jaguar

1963 Stratocasters (two sunburst, one Lake Placid blue, one white)

1973 Gibson Les Paul Custom

1980s Gibson Les Paul Standard (red)

1960s Gibson ES-355

1960s Rickenbacker 330/12

1960s Gretsch 6120

1960s Epiphone Casino

Amps

1965 blackface Fender Deluxe Reverb

1960s blackface Fender Twin Reverb

1950s tweed Fender Bassman

1970s HH Musician transistor amp

Effects

Lovetone Brown Source

Lovetone Doppelganger

Menatone King of the Britains

Carl Martin AC-Tone

Carl Martin PlexiTone

Carl Martin Headroom Reverb

SIB! Electronics Mr. Vibromatic

Electro-Harmonix M9 Mellotron

Line 6 DL4

Diamond Compressor

Boss GT-100 Multi-Effects Processor (live)

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Power Slinky strings (.011–.048)

D’Addario acoustic strings (.012–.053)

Ernie Ball Medium picks

I think we’re living in a really interesting age where there are sooo many pedals and tones available, which I’m excited about despite the option fatigue thing.

Could you tell us about your love affair with the Fender Jaguar? What makes them the perfect guitar for what you do these days?

What makes it so good for me from a technical point of view is the scale length, the radius of the fingerboard, and the way they set up—when they’re done right—steers me in a direction that really accentuates the way I play. It doesn’t invite me to play too bluesy, and it makes me want to play in a way that really rings out the notes, and if I want to get more rock ’n’ roll or bluesy, I have to make a real conscious decision to do that on these guitars. Part of that is because the fingerboard radius makes it more of a chore to play that way—sort of the opposite of a Les Paul. There’s also something about the way they sit on me, as an instrument, that makes them feel very lively. I tend to play louder than people might imagine, but with a light style, and that gives me an opportunity to really pop it sometimes and dig in, and the Jag has a lot of dynamic range in how responsive they are. The way the whole thing comes together harmonically cuts through the mix out front really well, too. I tend not to play a lot of moody bass note-y things, and a Jag pokes through in the upper mids in a way that really suits my melodic sensibilities. When I’ve played with other guitarists, my guitar tends to sit just a bit above everyone else’s Les Pauls and even Strats, and that kind of suits me well. Presence is a good word for it, but not like some horrible bright machine, which is a reductive and inaccurate way of looking at a Jag.

Jaguars can be a complex instrument to set up. Could you explain how you like to run your Jags, and perhaps any tips you have for getting the most out of one?

I find you absolutely have to have .011s on a Jag. No question on that! Guitarists that are used to playing with .010s on other guitars will find a Jag with .011s will behave in a way they understand. I personally set up my Jags so they have a little bit of fight in them. I won’t say high action, but they’re certainly not set up for fast shredding, and that gives it some real punch when you’re playing rhythm, and some real wallop and bottom end. I have a little shim that I put in the neck that’s .6 mm, and I find the neck angle is crucial on Jaguars, more so than almost any other guitar. The neck angle and the string break across the bridge really needs to be fine-tuned, but I’ve got it down now, between myself and my tech. It’s all about string tension with them.

How many of the iconic guitars from your past do you still have? Some of those instruments have taken on a life of their own, for example, Ryan Adams bought a red ’80s Les Paul Standard and fitted it with a gold Bigsby because he’s such a big fan.

I’ve still got all of those guitars! I should say that the red ’80s Les Paul that Ryan’s so fond of is an exceptional guitar, and I used that one on this record on quite a lot of arpeggio parts to double-track what I would do on the Jag. You hear the ES-355 from the Smiths days on “Hi Hello,” but I find I’m able to re-appropriate that sound really well with my new blue signature Jag onstage. I’m surprised with how well that’s turned out. I still have that green Telecaster that a lot of fans talk about—weighs a ton! I’ve got all the old favorites because I really love ’em. I still have the first Smiths guitar, the Gretsch Super Axe, and my black Rickenbacker 12-string was used on “Day In Day Out.” I also used the Epiphone Casino, which I wrote a lot of Meat Is Murder on, and a white ’63 Fender Strat from those days.

All of those guitars had a real direct effect on my songwriting back then, simply because it was so incredible to me that I was able to own each one of them. I had been so broke as a kid that I wrote a whole load of songs as soon as I got one of those guitars, and that was a rule I had for myself to justify buying one. The only Smiths guitars I don’t have any more are the ones I’ve given to Noel Gallagher and Bernard Butler.

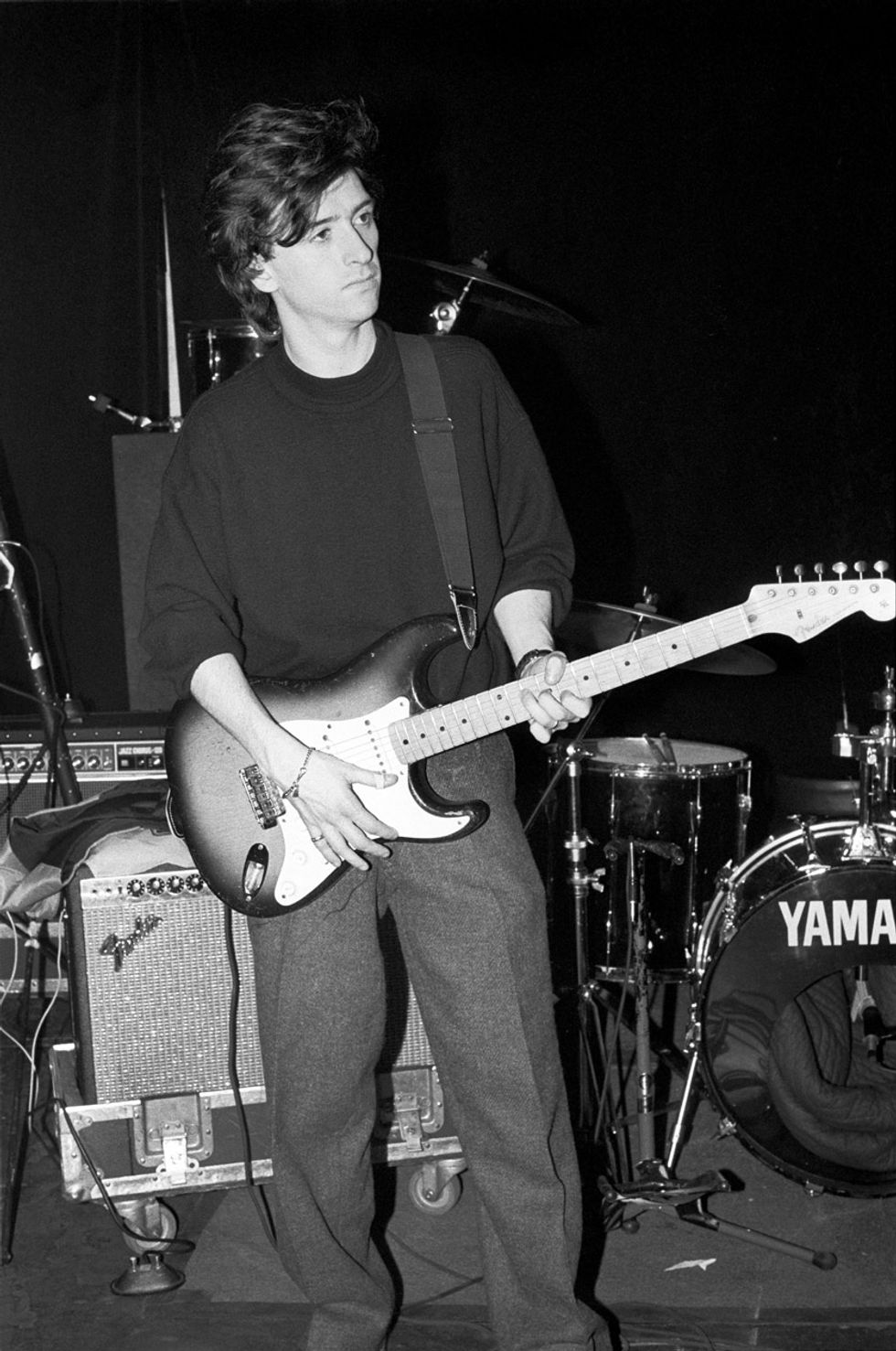

In this photo, a young Johnny Marr plays a sunburst Strat while rehearsing with Bryan Ferry in December of 1987, just months after Marr left the Smiths. Photo by Ebet Roberts

You bought a lot of guitars from John Entwistle of the Who, who had a legendary collection. Could you tell me more about what you got out of that collection?

The main one for me was the mid-’60s Gretsch 6120 that I believe was on the wall in that famous scene in The Kids Are Alright, where he walks down the stairs and has all the guitars on the wall. I wondered for a while if it was the one Pete Townshend used on Eric Clapton’s Rainbow

Concert, and it might be ... it really does look like it is. That one is a really radical guitar, so beautiful. I also got a couple of sunburst 1963 Strats from him, my ’60s Lake Placid Blue Strat, and the Fender Bassman I mentioned earlier.

How did that deal happen? I’ve heard he actually approached you.

Yeah! We have a mutual friend in Alan Rogan, who is the Who’s guitar tech. John knew that Alan was doing some work with me and Alan guided me towards it and thought I should have some guitars. Alan pretty much marched me ’round to John’s and made me buy them! He also made me buy my vintage Fender amps that I still use to this day.

I assume that includes Pete Townshend’s former 1960 Les Paul Standard that Noel Gallagher allegedly stole/borrowed indefinitely from you?

You know, he hasn’t really stolen it. It’s very much his guitar and I should say that for the record. He’s also got the black 1973 Les Paul Custom that I wrote and recorded The Queen Is Dead on. I gave him that back in the days when I was drinking and he needed a guitar, and I didn’t want to give him something terrible. Bernard Butler has my sunburst Gibson ES-335 12-string, which I used a whole lot on Strangeways, Here We Come and “Shoplifters of the World.” I’m honestly really happy about those guys having those guitars: They went to really, really good homes.

With Noel, I had no idea he was going to be a big success! He was just a guy who I liked who needed helping out. Strange how things turn out, but we all need a bit of help now and then. I’ve certainly had people help me out before, so it all works out.

The track “Bug” is such a banger of a rock ’n’ roll song, and sounds like something a band would write just jamming in a rehearsal space. How’d that one come about?

I was kicking around at home on the Jaguar with the capo on the 4th fret … surprise surprise! That combination’s been good to me over the years. When I was young and got into capos, for no educated or logical reason, I had a feeling the guitar just liked having a capo on the 4th fret. It was a super instinctive decision and, over the years, people thought it had something to do with the key myself or Morrissey preferred to sing in. But the truth is, I just felt like the guitar was happy there, and “Bug” was one of those where I threw the capo on there and before I knew it I had that intro riff. It all came together quickly. To be fair, I was sort of imagining how the Clash would have sounded were I in that band, so that was my lateral thinking.

When I have that scenario with a riff first, especially an electric guitar riff, I just program a basic beat to get the demo down, and I like to get a vocal down very quickly and work around that. That was something I did in the Smiths days, too. I learned not to be that guy who has got this killer backing track that you spent a week on, but then you have to climb the mountain and turn it into a real song. So, I like to have most of the vocal worked out before I get the band in, and that’s the frontman in me, I think.

Photo by Niall Lea

I don’t believe it’s a stretch to say the defining feature of your career is your brilliance as a collaborator. How do you approach placing your guitar in so many varied contexts without drastically altering your playing style?

One of the things that was handy for me was the way I learned, because I learned playing along with records. I was copying things off maybe something by T. Rex or Sparks, and studying how the guitar fit in with everything else, rather than just putting my head down and concentrating on me and no one else. So, much of my early learning was about listening to and analyzing records, and not just the guitar parts. Wanting to copy what was going on with an organ part and focusing on those chordal swells or the voicings underneath a verse, or even things like big pianos playing single notes to punctuate the accents on a song ... that kind of thing really taught me a lot. When it comes to playing with other people, especially if another guitarist is taking up a lot of space on record or onstage, I’m aware that there are a lot of other places where you can add some color and accentuate things, rather than defaulting to two guys trying to make some sort of a mosaic of guitar. That thing can be cool, too, and I know how to do that from being a big fan of the Rolling Stones in the mid-’70s and trying to work out how those two guitars got together.

I guess I had this idea early on as a guitarist about being appropriate, and sometimes being appropriate means being really big, and I did that a lot in the The. To maybe look at it a bit simplistically, I know that if I’m guesting on a track or onstage with somebody, it doesn’t necessarily mean I’m supposed to be the loudest or most constant thing on the track. It’s got to be music and it’s got to fit the arrangement! That sensibility is probably why it’s worked out for me on a lot of other people’s records. You have to know that the music’s way more important than you.

According to Marr, string tension is the key to playing Fender Jaguars. Here he is with his signature model in sherwood green. “I personally set up my Jags so they have a little bit of fight in them,” he says. Photo by Debi Del Grande

You’ve done a lot of soundtrack work for major films in recent years, working alongside the great Hans Zimmer. How has that work changed you as a player?

What it’s brought to my playing is a certain freedom to really go whichever way I want. Hans generally wants me to find a killer melody to work over his chords, and it’s nice that I’m given that job. I follow emotional themes in the movie and try to find melodies that fit them, and Hans uses me to be both melodic and atmospheric, and abstract, which is a pretty fun combination. I’m not thinking about what it’s going to be like onstage, which is how I think when I write for my own records, and I’m not thinking about arrangements. Another important part of playing with Hans, which I think is obvious, is that we really go for something dramatic.

I’ve seen photos of Hans Zimmer playing guitar. How’s his guitar playing?

He’s a really interesting guitarist! He learned all the prog stuff when he was a teenager and he’s a damn good rock-guitar player, but he likes breaking the rules, so he plays weird homemade guitars and cigar-box guitars. It’s a combination of wanting to be maverick and knowing a few killer Steve Howe riffs. He’s really good when he wants to play, though he’ll say he’s much worse than he really is.

You work your guitar in around electronic elements a lot. A great example on this album is the track “Actor Attractor.” Do you have any advice for guitarists struggling to write and play on tracks with big synth sounds?

Yeah! When I first started layering guitars on top of a lot of synthesizers in the late ’80s with Electronic and the Pet Shop Boys, it was a challenge and I spent an awful lot of time trying to match the guitar sound with that of the synth. I don’t do the sound matching so much these days. I think so much of it is about the part specifically, and then making the sonics fit the part. If the part is right, you can grab an ES-335 and put it through a Vox amp and I’ve found that often will sit nicely on a synth bed or a synth pulse, and almost do more honor to what that guitar sounds like, which I find offers some contrast and is more interesting than trying to bury a guitar in with the synths. Over the years, I’ve found a bluesy guitar sound over a synth pulse really works for some reason.

On “Actor Attractor,” I found I could help the guitar join the party by making it very, very backwards and atmospheric, but I still didn’t try to make it sound like a synth. I honored what the synth was and let it be its own thing and then tried to imagine that the guitar was in a similar mindset, and asked what would be a similar mindset to a moody, dark synth? Backwards immediately came to mind and, hey, I think it did the trick. The other guitar sound on that track is my Jaguar through the nasty transistor HH amp. So, if you’ve got to find something that complements a synth, it should have more to do with attitude than sonics.

I’m a fan of the rockabilly side of your playing, like the Smiths’ “Vicar in a Tutu” and “Nowhere Fast.” Are you still interested in that kind of playing, and is it something you still mess around with at all?

I guess it was such a big part of that period of the Smiths, from early ’85 to late ’86, and I associate it with writing a certain kind of song. The last few years, I’ve remembered how much I like Les Paul as a guitarist, and if you listen to his more sparse stuff, like his version of “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles,” it’s really futuristic in the realest sense. That’s something that I’m attracted to these days in that sound, but I wasn’t thinking like that back in the day. I just really liked the approach to the guitar on early rock ’n’ roll records: Scotty Moore, Cliff Gallup, Eddie Cochran, that great thing that those rock ’n’ roll guitars had on records, including acoustics! But my interest in the ’50s guitar now rests much more on the ’50s idea of futurism. I must confess I’ve been wondering about that sound and approach again, but I don’t know if rockabilly songwriting is where I am these days. So much of those great rockabilly records are really about the singer singing in a ’50s kind of style and the guitar is a great adornment for it, and I really do love what those records are about, but I haven’t really thought about writing in that direction for a really long time. I still like them as a listener and a guitar fan.

Do you have a guitar contribution to the Smiths that you feel is underappreciated?

A friend of mine is completely nuts about “The Draize Train,” and when he plays it in the car, there are some pretty good things going on in it. There’s a sound that people assume is a sequencer on there—especially because I’d been working with Bernard Sumner of New Order around then—and it’s actually a really badass Les Paul Custom through a gate. The very fact that I wasn’t using synths made that approach quite unique then. And there’s a thing I did with harmonics on that track, which I quite like.

I think the whole of the last album, Strangeways, Here We Come, has some good moments of guitar on it that I was really working on. “Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me” has some good stuff on it, sort of a guitar orchestra going on. The little figure on the end of “Well I Wonder” was always something that I liked. What I was doing with echoes and delays that people didn’t notice so much—but things like the outro on “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others” and things like “Half a Person.” In all honesty, I think over the years I’ve been fortunate to have had a lot of stuff appreciated, like nothing hasn’t had the light shined on it at some point. That isn’t false modesty, but when I really think about it, people have mentioned liking quite a lot of that stuff along the line, and I appreciate the thought!

In this live video from Conan O’Brien’s talk show, Johnny Marr and his killer band crack into “Bug” off of Call The Comet.

Johnny Marr in full flight with the Smiths on the German live music program Rockpalast in 1984.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)