A group shot of the early Funkadelic ensemble circa 1970. Standing, left to right: Clarence “Fuzzy” Haskins, Lucius “Tawl” Ross, Bernie Worrell, Ramon “Tiki” Fulwood, Grady Thomas, George Clinton, Calvin Simon, Ray Davis.

Seated: Eddie Hazel and Billy “Bass” Nelson (supine).

It’s difficult to overstate the influence of Parliament Funkadelic. They helped shape the sound of the ’70s, and, along with James Brown, pioneered funk and became the foundation of hip-hop. Literally. Their grooves have been sampled, looped, and rapped over ad infinitum. The band is still touring, releasing new albums, and George Clinton—P-Funk’s ringleader and mastermind—was recently nominated for a Grammy for his role on Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 release, To Pimp a Butterfly. (Be sure to check out our sidebar that celebrates the eight main guitar players who paved the funky way.)

Of importance to 6-stringers, the guitar is central to P-Funk’s sound. On the heels of their first hit, 1967’s “(I Wanna) Testify,” the doo-wop group the Parliaments morphed into the psychedelic Funkadelic. Built around Eddie Hazel’s fuzz-drenched leads and Tawl Ross’ steady rhythmic chunk—and inspired by artists like the MC5, Vanilla Fudge, and Jimi Hendrix—Funkadelic redefined R&B. They were loud, audacious, outrageous, and infinitely groovy. In the 1970s—and with the reintroduction of the name Parliament—the band grew into a collective of about 50 musicians and perfected their infectious brand of funk. By decade’s end, they were selling out stadiums, selling millions of albums, and charting hit after hit.

It’s no surprise P-Funk attracted top guitar talent. In addition to Hazel and Ross, their roster included Garry Shider, Cordell “Boogie” Mosson, Michael Hampton (aka Kidd Funkadelic), Ron Bykowski, Glenn Goins, Bootsy Collins, Catfish Collins, DeWayne “Blackbyrd” McKnight, Ricky Rouse, and many others. “All of them played guitars except for me,” Clinton says. “I was good for humming lines for guitars. But I don’t have dexterity for shit.”

the tradition going.”

We wanted to find out about the history, tones, tricks, gear, and great guitarists—both past and present—of Parliament Funkadelic, so we went straight to the sources. We spoke with Clinton, Hampton, McKnight, and Rouse and crafted this roundtable of sorts. Sit back, prepare yourself, and get ready to learn some of funk’s deepest guitar history.

The way you used guitar really distinguished P-Funk from other funk groups, especially on the early Funkadelic stuff. What was your initial inspiration for that?

George Clinton: Well, for that, of course, it was going to be Jimi Hendrix. Right when we did “(I Wanna) Testify,” it was changing from the Motown era to rock ’n’ roll—European style. Rock ’n’ roll was coming back into the States all amped up. A friend of mine, her name was Nancy Lewis, was friends with Pete Townshend and Jimi Hendrix. We did a compilation record [Backtrack, Vol. 6] with them—“Testify” was on the record—on a thing called Track Records over in Europe, which became the Northern Soul Company. I saw those amps up at the girl’s house and we also played on Vanilla Fudge’s equipment one time. We saw that big sound—how it was created—and we just started buying up amps. I got Eddie Hazel two Marshalls—the one-piece Marshall [8x12 cabinet], not the half-stacks like they got today. It was one tall piece. That was the beginning of our psychedelic era—him and Billy Bass [Nelson]. When I got them started, they were just starting to play an instrument. Guitar became part of our changeover from the doo-wop time—from singing with vocals only, to a real loud guitar. Eddie Hazel learned very well. He had a Gretsch, a big-body guitar, at first.

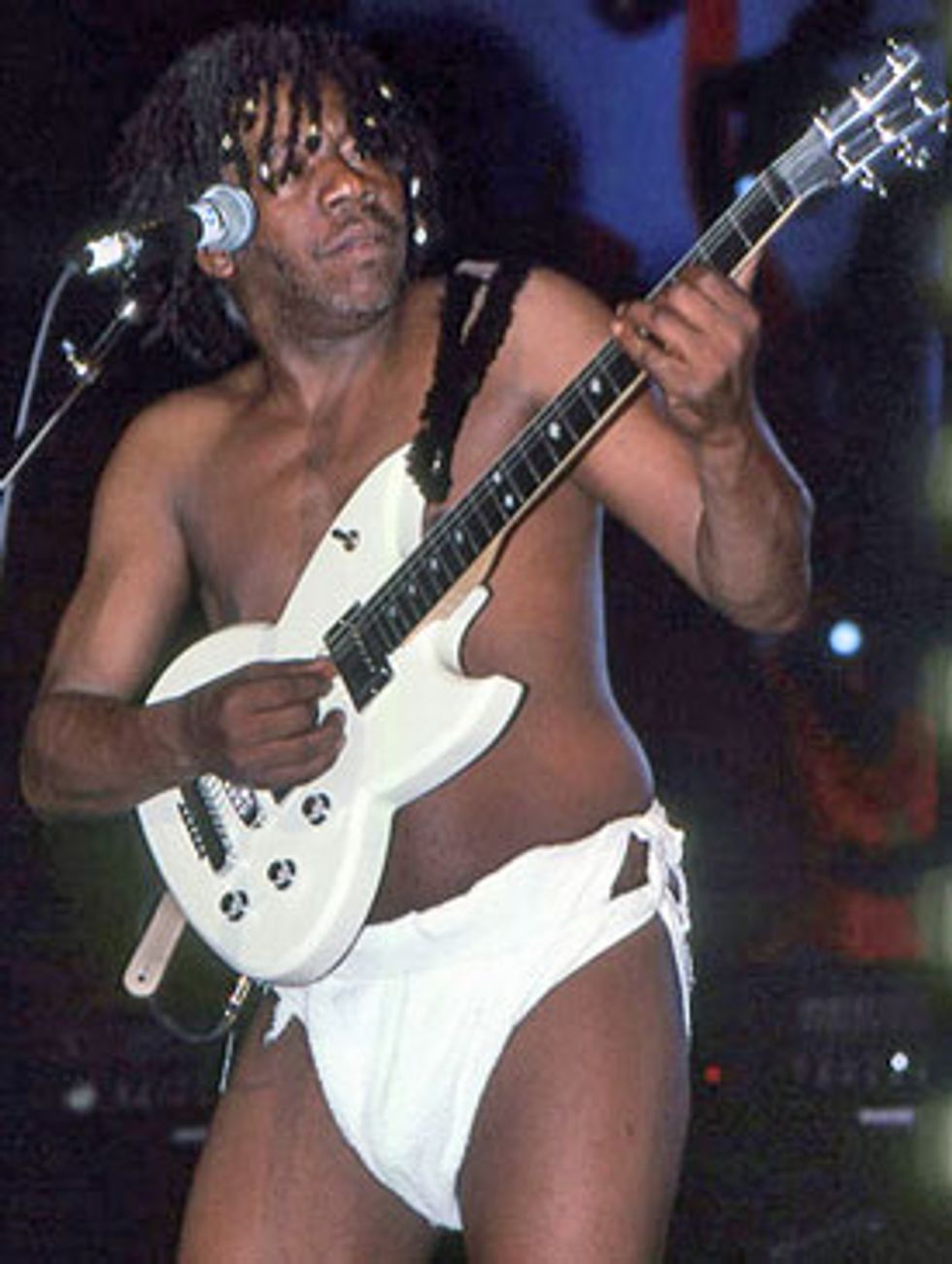

Guitarist Gary Shider gets down during the P-Funk's Woodstock ’99 set. Photo by Frank White

A big-body Gretsch? I didn’t expect that.

Clinton: Then we got him a Strat. It didn’t matter to him. It could be a Kay or anything—he could make it sound the same. He learned so good—the Jimi sound and techniques. We were able to jump out ahead of most people from the R&B side. When we did “I Bet You” from the first Funkadelic album [1970’s Funkadelic], and then Free Your Mind…and Your Ass Will Follow, we deliberately went off to be really psychedelic. We knew we wanted to set a foundation so that we’d never have to worry about making a commercial record again. We went so far out there with the guitar on purpose on Free Your Mind…and Your Ass Will Follow that it became our signature—that loud, nasty guitar.

Back in the early days when you were first using all those big amps, was Eddie using pedals as well? How did that progress over time?

Clinton: Eddie started right out learning the pedals—the wah wah, the Big Muff, and phasers and shit. We bought all the gadgets in the world, [especially] once Bootsy got with us.

Blackbyrd McKnight: When I first got there, I had a Fender Stratocaster. I think EMG pickups had just come out in the early ’80s and I quickly gravitated to them. Other than that and a little preamp I used in my guitar, we were using Music Man amplifiers. I recall having an MXR Distortion +. I used a compressor—it probably was the Roland compressor at the time. I think I had a chorus pedal, but I can’t remember what brand it was. And I think that was about it because the Music Man amps were killer. I was told they were owned by Aerosmith. They were beefed up and they sounded absolutely great. I was a pedal guy and I loved playing with all kinds of pedals, but with traveling and carrying cords and pedals—this was before pedalboards and all of that stuff, for me anyway—I took a couple of things out. But the amps were more than enough to get that tone.

Michael Hampton: At that time, I think they had Aerosmith’s old Music Mans—their old backline. They had a Crown power amp, too. So they had the Music Man and then they had them running through the Crown to the speakers. The guys working as techs back then knew how to modify all that stuff. They could go in and modify whatever was happening with that amp. And they probably made that amp hotter. If it had anything to do with the tubes, whatever they knew how to do, it was probably responsible for that tone.

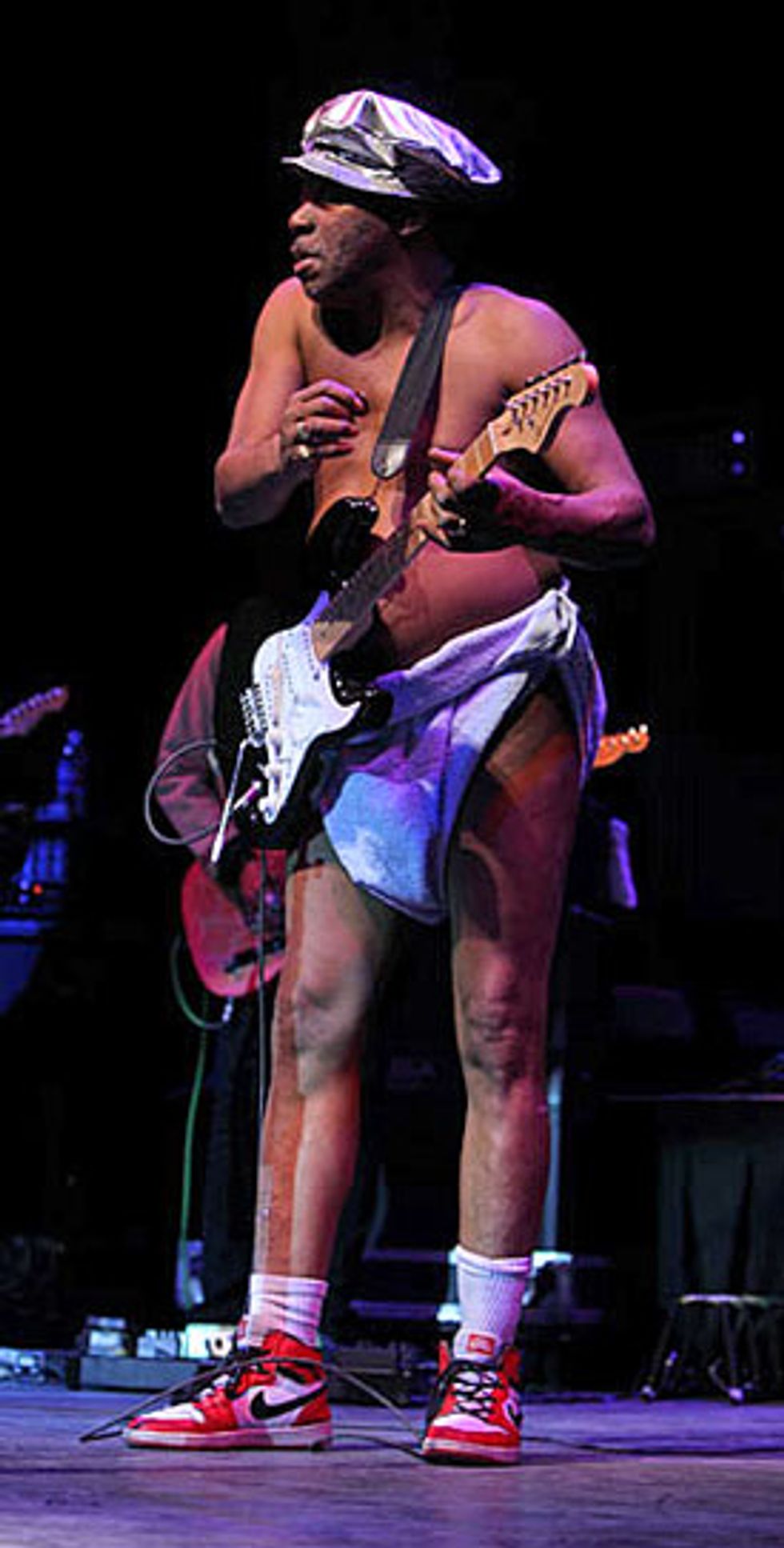

According to Parliament-Funkadelic architect George Clinton: “The art of playing rock ’n’ roll guitar on an R&B record is: Play the melody of the singer’s part, go off and do your psychedelic thing, and then come back to the melody.” Photo by Tim Bugbee - Tinnitus Photography

Compositionally, were the guitar players free to find their own voice to express themselves? Were you dictating lines or creating parts for them?

Clinton: No. I did that once in a while, but there was no need for me to do that. I had too many people that could do that for real. So I didn’t. But every once in a while I would have something to say. Just something I felt, and they were pretty good at interpreting anything I said.

Ricky Rouse: George lets you do what you can do. He knows how to use whatever you’ve got. Everybody gets quite a bit of freedom to do whatever they want to do.

McKnight: Once in a while George would sing a part he wanted me to incorporate in a song and I would do that, but for the most part he gave us creative control.

What are some of the basic building blocks you use for soloing? Harmonically and melodically, how do you approach it? McKnight: I just play what I hear. I didn’t really have any type of formula or anything other than all the influences I accumulated over the years—that was about as deep as I got with any sort of music theory with that band. One of the reasons I wanted to play with that band was artistic freedom, as it were. I listened to a bunch of jazz and rock and I always liked fusing those two together—that was about the only process I went through. Wherever the song was, I did what I thought would fit. George never said anything about what he wanted. He would turn on the tape—or the engineer would turn on the tape—and they might say to face a certain way to get the hum out or whatever, and that was about it.

Hampton: When I was starting to find out about different scales, I would experiment on how to resolve, say, a diminished to a major, or do a diminished scale or an augmented and then resolve it to a minor. I mean, as long as it’s not too far away from the modes. I experiment a lot. If I’m playing something, I want to do as many variations on it as I can. It depends on the progression and whoever is producing it or what they think they might hear. They might have a vocal track on there already so I’m either trying to do something that complements the vocal or I’m trying to actually do the same thing as the vocalist. That would be my foundation, and then I go off from there and I try to enhance whatever the progression is. But I really don’t think I gave it a whole lot of thought, like, “I’m going to deal with it like this.”

Clinton: Michael Hampton came in and took Eddie’s place. He had that sound and he learned very well when I told him that the art of playing rock ’n’ roll guitar on an R&B record is: Play the melody of the singer’s part, go off and do your psychedelic thing, and then come back to the melody. For example, “One Nation Under a Groove,” “(Not Just) Knee Deep,” “Never Buy Texas from a Cowboy”—he learned those concepts so well and he always had real good sounds on his guitar.

Hampton: When I was really young, our teacher took the whole class to see the symphony orchestra. I was fortunate enough to check that out, and something about it just set something off—when I hear certain songs and the way they use the modes. I’m looking for what it makes me feel like, you know? Like wonderment. I’m trying to paint a feeling of whatever feeling I have. Most of the time it’s kind of minor-ish. But I love all of the different modes. It interests me on how to resolve it.

Michael Hampton, aka Kidd Funkadelic, plays a B.C. Rich doubleneck at B.B. King’s in New York circa 2012. Hampton was a teenager when he joined Parliament Funkadelic, landing the gig after impressing the band with a rendition of “Maggot Brain” at an after-party in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. Photo by Joe Russo

I also try to put solos in there like how a drummer does a roll. He plays a drum roll and sets it up for the melody. I’m always listening for that resolution. I might wander around in some different modes or scales, but I’m interested in trying to resolve it right on, at a time where people should understand it. It could be a slow or fast lead, but whatever it is should resolve. “Oh, here it comes right here. Okay.” And bring it back home.

How does your tone change when you’re in the studio—do you sit in the control room or do you stay in the room with the amp?

Rouse: It depends on what we’re trying to do. A lot of times when you’re just playing rhythm you can do it right there at the board. And if you’re playing some lead stuff, you go out there and wire the amp up and put it through like that. George likes the power from the amp, but I’ve cut sessions with him where I just sit in front of him at the board and do it.

Clinton: At United Sound [in Detroit], we had separate rooms that you could put a man in. Even in Toronto—we did a few of the songs like [1972’s] “America Eats Its Young” up there—those big sounds. And sometimes we’d just do straight up rock ’n’ roll—everybody in the same place and we’d just turn it up loud.

Hampton: For one solo, I was outside the booth and the amp was isolated in the vocal booth. For the “(Not Just) Knee Deep” solo, I think it was a Fender Twin cranked all the way up. They had those microphones that stuck to the glass. But in order to get that sound, they isolated the amp. I’ve done both, like, where I’m with the amplifier, like on “Butt-To-Butt Resuscitation”—I didn’t name that by the way [laughs]. I was using my Alembic guitar, I forget what the model was, and there was a Morley wah and I think they had a Marshall stack. I was basically right next to the stack when I did that solo. I prefer to be right next to it, for feedback and other effects.

Blackbyrd McKnight (left), Rickey Rouse (middle), and Michael Hampton (right) jam out with Parliament Funkadelic at the 2015 NAMM show

in Anaheim, California. Photo by Alex Matthews

With so many guitarists—plus keyboards—playing together, how do you keep from stepping on each other’s toes?

McKnight: We just listen as well as we can. At one point we had a mixer onstage—everybody had a speaker of somebody else’s on the other side of the stage. Everybody had at least one cabinet of another guy, so we listened and if one guy was playing the parts he played on the record, you’d play something that was relatively close to what he was playing but not step on his toes, and the same with the keyboards, because you could hear everything. The thing for me was being able to hear everything so that you didn’t overdo it.

Michael, there’s a video online of “Red Hot Mama” and you’re playing a guitar that looks like a Strat but it has a reverse headstock and it’s got three humbuckers. What is it and how did you get it to sound so good?

Hampton: It’s a Strat. I put the left-handed neck on and three DiMarzio Super Distortions—I just went crazy with that guitar. I had an Alembic preamp they made back in the day—that kind of blew out later. I always liked funny cars and hot rods and that’s basically as close as I’m going to get for the guitar [laughs].

Plus, I would just crank the guitar, man. I would turn it all the way up. Most of the time everything would probably be at 10. I guess it came from the pickups itself and the actual makeup of however it resonated. I pulled the saddles all the way back, too, so I could get more flexibility and more play in the string, and it wasn’t intonated correctly. The guitar was intonated with itself—if I hit everything open and you gave me all the strings open on the keyboard, then the guitar would be kind of out. But that might have a little to do with the tone, too, because there was more play in the strings. But it’s got to be those preamps, that Alembic preamp was probably working at the time, and those Super Distortions along with it probably gave it that tone.

Not to give it all up to me, but some people actually say it’s in your fingers. And I guess there is some truth to that, but I’m just trying to stay humble on that one. I’m pretty sure we’re talking about the electronics [laughs]. And the strings probably were definitely somewhere near new. Because I used to change them every two gigs or something, keeping the strings fresh.

How does Parliament Funkadelic write songs? Does the group jam and you find a good line or do people come in with ideas?

Clinton: Most of the time we start off with a good line that started as a vamp or something onstage and we make a song out of it. When we get into the studio, we come up with licks and grooves and we just take them from there. Most head sessions are done in the studio, everybody [throws in ideas], and then we put the words to it. Once in a while I have a song written beforehand and then we do the track after it. That would mean [keyboardists] Junie Morrison and Bernie [Worrell] would have to do arrangements as opposed to head sessions—they would have to figure it out prior. “Knee Deep” was one of the best of those types of songs.

Rickey Rouse has played with Stevie Wonder, Chaka Kahn, Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and even Tupac. “Look at his resume, watch him onstage—the dude is one badass dangerous guitar player,” says Blackbyrd McKnight about Rouse.

Photo by High ISO Music

Can you name an example of a jam that started onstage that you turned into a song?

Clinton: “Shit, Goddamn, Get Off Your Ass and Jam.” Almost all of the songs, because like I said, there would be a lick or something and we’d go into the studio and then put something to it.

Do you rehearse new material or is it cut live in the studio?

Rouse: It’s pretty much cut live; we don’t have to rehearse. George tells you what he wants and he’ll give you the freedom to put your thing on it and that’s how we do it. The only time we really rehearse is if we’re going to do a TV show or something like that where we have to have a set list. He is a very good orchestrator in the studio as well as live. He knows how to control the audience and the band at the same time. It’s never really a set show. We have certain things that might happen, like we might end with “Atomic Dog.” He might pull some song from the first album or something like that. But he’s pretty much in control of the thing.

The P-Funk Guitar Army

We can’t say for sure how many guitarists played with Parliament Funkadelic throughout the group’s six decades in existence. But we can offer this rundown of the eight main guitar players who paved the way.

Eddie Hazel

Eddie Hazel was Funkadelic’s original lead guitarist. He set the bar high. “Eddie Hazel colored the style of Funkadelic,” George Clinton says. “All the stuff leading up to Maggot Brain and afterwards—he set the style. Garry Shider—who was like his little brother—kept the tradition going.”

Hazel is lauded for his lead playing, particularly his iconic 10-minute solo on “Maggot Brain.” But his rhythm playing was just as important. “He had a way of playing rhythm where he used his fingers as well as the pick,” says Blackbyrd McKnight. “I understand that he got that style from his grandmother. His grandmother played guitar and he told me that he got a lot of that stuff from her—playing with the pick and the fingers at the same time with the rhythms. It was similar to how the blues players did back in the day—that’s what it sounded like to me.

“When I met him, he was actually a greater guitar player than I knew he was,” McKnight continues. “You’d go to a soundcheck, you’d listen to him play or you’d hear him play something on the gig—hard not to be influenced by that.”

Hazel appears on Funkadelic’s earliest albums. He was in and out of the band throughout the ’70s and ’80s and died in 1992. See Hazel in action in this early Funkadelic performance.

Probably the most mysterious of the P-Funk guitarists is Ron Bykowski. “Ron was the first white guitar player we had,” says Clinton. Bykowski appears on Cosmic Slop [1973] and Standing on the Verge of Getting It On [1974] and is credited as the “polyester soul-powered token white devil” on the latter. “He gave us that Les Paul sound, like the feedback on ‘March to the Witches’ Castle,’” Clinton continues. “He was the one that made us like a real rock ’n’ roll band early in our careers as Funkadelic.”

“Ron was the feedback king,” Ricky Rouse says. “He knew how to get all the different feedbacks from the way he positioned his body with the amp. He could move his body a certain way and get a different feedback and a different tone.”

“I think one of my favorite songs, ‘Red Hot Mama,’ is actually Ron Bykowski,” says McKnight. “Everybody thinks it’s Eddie, but it’s not. I’ve heard outtakes with Eddie on it and when the two of them are playing together you can definitely tell who’s who.”

Bykowski played in a number of Detroit area R&B bands before joining P-Funk, but fell off the map after leaving Funkadelic. “I know his wife didn’t want him to be in the group when he first got married,” Clinton says. “At that time we were always really out there on drugs [laughs] and he was hanging with Eddie, of all people, so, she had a good reason for wanting him back home.”

Although live videos of Bykowski are hard to find, there is this.

YouTube search term: Funkadelic – Cosmic Slop 1973

(Ron, if you’re reading, we would love to hear from you.)

Photo by Ken Settle

Michael Hampton was just a teenager when he joined P-Funk, which is how he earned his moniker, Kidd Funkadelic. He landed the gig after impressing the band at an after-party in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. “My cousin was playing bass,” Hampton says. “I showed him the chords to ‘Maggot Brain’ and we played it in the living room. The band was around me. I didn’t know it was Eddie Hazel and [drummer] Tiki Fulwood—it was the whole band—Garry and Boogie. They were all there and they heard me play.” He did his first gig two weeks later. “I did my first show in Landover, Maryland, at this place called the Capital Centre—now it’s a mall—but that was the first place that had closed-circuit TV sync. I looked up and I started off the set—it was sold out and I started off the show with ‘Maggot Brain’—that was all I used to play.”

Hampton developed into an amazing guitarist. “The thing about Michael is that he listens to everything that’s going on in a song,” McKnight says. “He listens to the chord formulas that are being used, the key in the chord formulas, the scales, the alternative scales you can use. He was that scholastic guy that would throw all of that stuff in there and really make it make sense.”

What’s on the horizon for Hampton? He’s open. “I’ll just keep on practicing and wait until the next house party [laughs]. Maybe I’ll catch somebody’s ear out there and something will jump off.”

Check out Hampton’s incredible solo opening this version of “Red Hot Mama” and note his heavily modded Strat.

Catfish Collins

Catfish Collins—older brother of Bootsy—was a guitarist with James Brown before joining up with Clinton. In addition to his work with Parliament Funkadelic, he also played on other P-Funk projects like Bootsy’s Rubber Band and the Horny Horns.

“If you listen to Bootsy’s music, Catfish’s guitar tracks are woven together,” McKnight says. “It would be two guitars layered over each other and it just meshed. It was like one guitar.”

Collins was active until his death from cancer in 2010. Check out his iconic rhythm work on the Parliament mega-hit “Flash Light.”

Photo by Alex Matthews

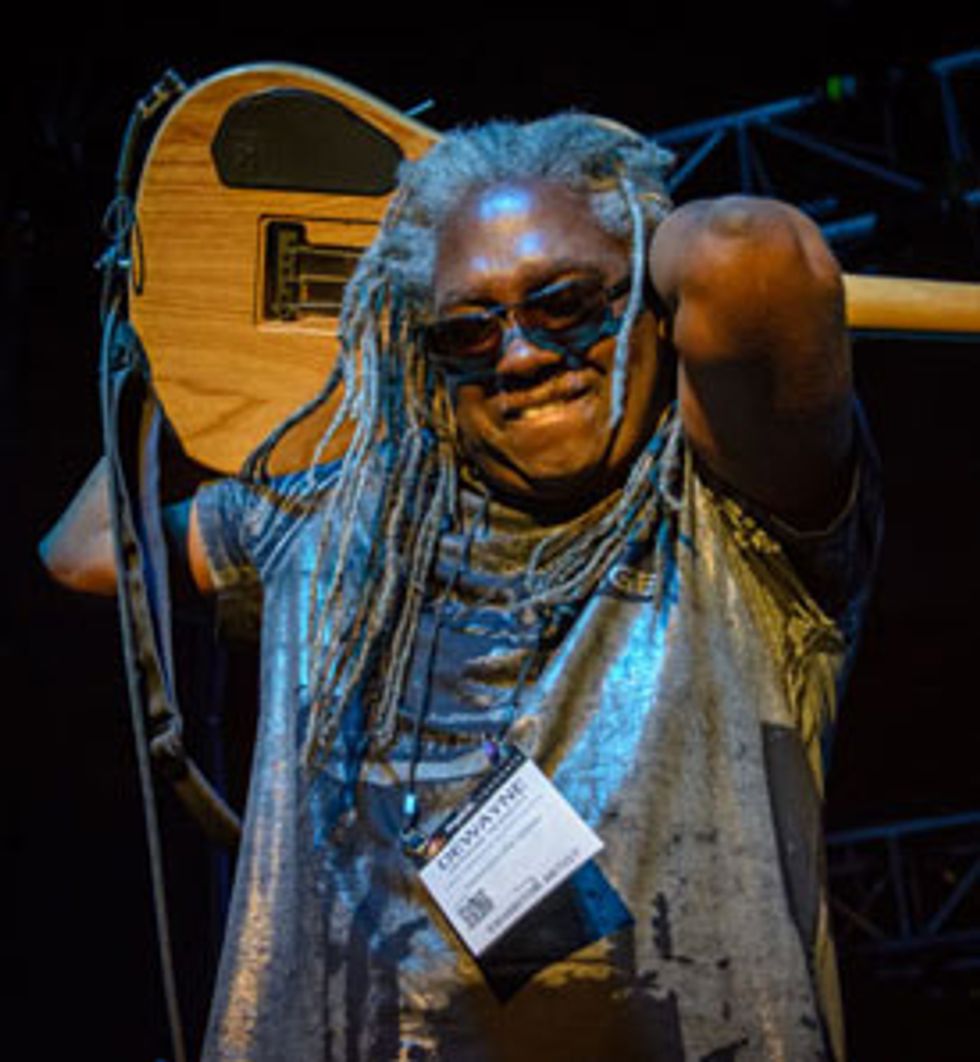

“Blackbyrd McKnight is one of the greatest guitar players around,” Clinton says. Prior to joining P-Funk in 1978, McKnight was in the Headhunters and worked with jazz legend Charles Lloyd. “He was in the band with Dennis Chambers—they were the Brides [of Funkenstein] band—and they were the band that just kicked Bootsy’s ass and our ass.”

McKnight grew up listening to jazz and bebop lines, which are an integral part of his playing. But Hendrix was also a huge influence. “I was in junior high school when I saw Hendrix the first time.” McKnight says. “He opened up for Eric Burdon and the Animals.” Seeing Hendrix also influenced his choice of gear. “I used a Vox wah until the Dunlops came out,” he says. “I liked the chrome-plated one. Everybody liked the Cry Babys, but I liked the chrome-plated ones. Those were the ones I saw Hendrix use. I never saw Hendrix use a Cry Baby.”

McKnight has also worked with artists as disparate as the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Bill Laswell, H.R. of Bad Brains, and Macy Gray.

This video features a young McKnight with the Brides of Funkenstein in 1979. In addition to his incredible rhythm playing, check out his solo feature at 10:54.

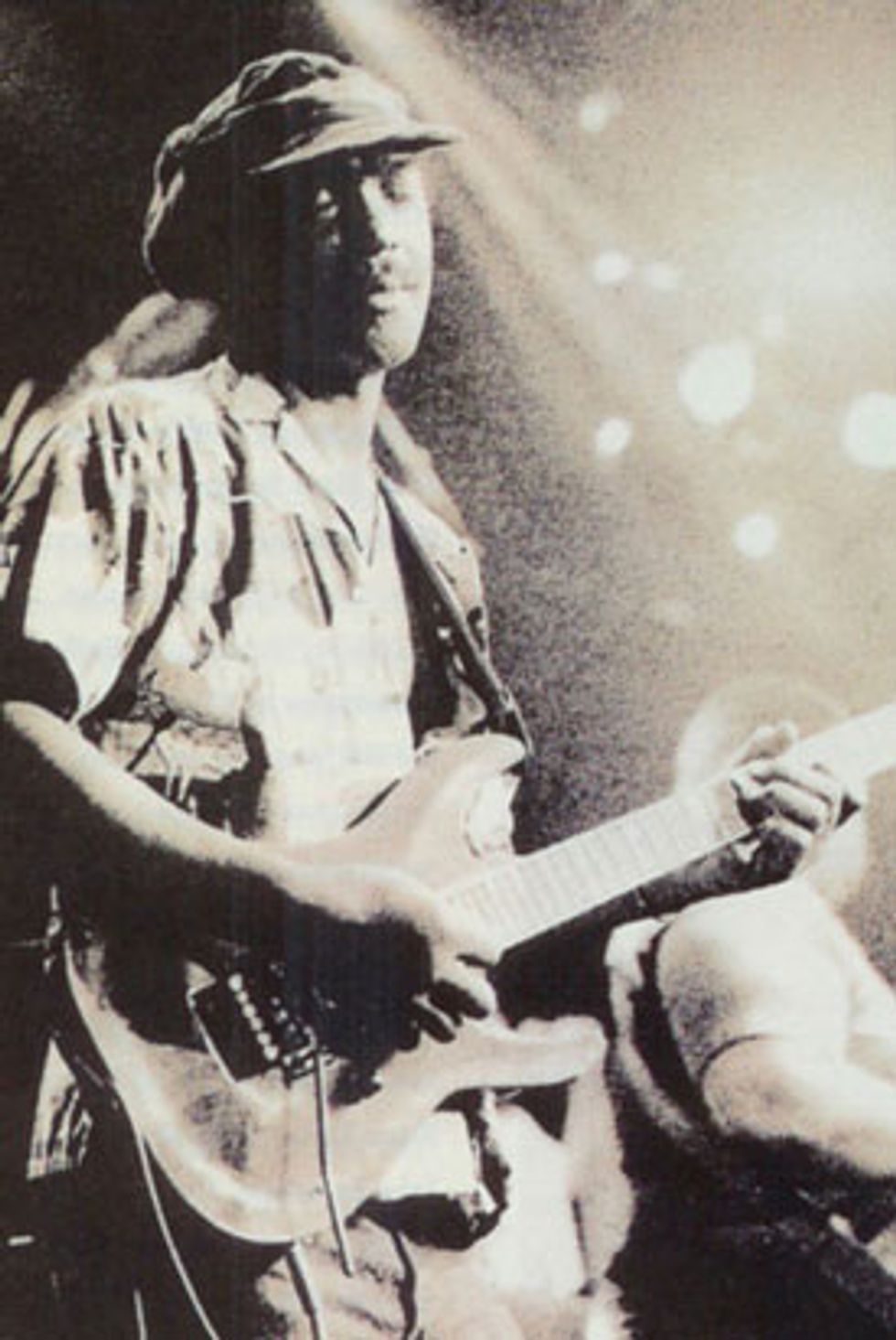

Tawl Ross was the rhythm guitarist in the original Funkadelic. “Tawl was a genius of rhythm,” Ricky Rouse says. “He had that attitude of Funkadelic—him and Billy [‘Bass’ Nelson] had that rock ’n’ roll attitude. It made it real because it was messing everybody up.”

“He was playing the rhythm—the chunka chunka chunka,” Clinton adds. “He played the strong rhythm on the first Funkadelic albums. He had the rhythm and the psychedelic image down pat. He and myself were the first ones doing punk rock—just prior to Iggy [Pop] and them doing it in Michigan. When we started playing with them, we saw that Iggy was doing the same stuff we were doing. We were wearing the diapers and being real sick on the stage. They called us the bad boys of Ann Arbor.”

“Those guys were what they played,” McKnight says. “That was them. Their style was what they were. You figured there was an engineer that put an echo—the way that Tawl would play with the echo and play rhythm behind—well that was Tawl. It wasn’t the engineer.”

Listen to the 1970 track “Fish, Chips, and Sweat.”

Photo by High ISO Music

Photo by High ISO Music“Look at his resume, watch him onstage—the dude is one badass dangerous guitar player,” McKnight says. Prior to joining P-Funk, Rouse worked with Stevie Wonder, Bohannon, the Dramatics, and many others. He was in the studio with the Undisputed Truth in 1972, and that’s when he first met up with Clinton and company. “Ricky Rouse was around Detroit when we first started but never did get into the group until 2000-and-something,” Clinton says. Rouse joined in 2007.

In the early ’90s, Rouse hooked up with Dr. Dre. “I did Snoop’s first three albums,” Rouse says. “I was with Warren G when he had the G-Funk thing, and I played with Tupac because I wrote songs with Pac.” His last gig before joining P-Funk was with Chaka Kahn. “It was fun playing the guitar with her because a lot of her stuff was guitar-oriented. Tony Maiden’s a great guitar player.” But joining P-Funk is a natural homecoming. “I always knew the Funkadelic stuff because they were my favorite band. I never rehearsed the stuff—I learned the stuff right there onstage when I came in the band. I knew the songs and I learned the arrangement right there.”

Watch this great clip of Rouse shredding in the studio.

Photo by Tim Bugbee — Tinnitus Photography

Garry Shider was from Plainfield, New Jersey, and knew Clinton from his days working at a barbershop there. Clinton produced United Soul—Shider’s band with Cordell Boogie Mosson—before incorporating them into the greater P-Funk collective.

“Garry wrote a lot of songs with George,” Rouse says. “Garry was a real singer and a great guitar player. He and Boogie came up through the gospel thing. He was a great rhythm guitar player and he could play lead as well.”

“Garry, Eddie, and Boogie had their own sound,” McKnight says. “It was like a Plainfield sound. It is hard to duplicate, but just great to listen to. They all kind of played the same—not the same licks, but the same feel, the same patterns.”

“Garry grew up under Eddie,” Clinton adds. “He was much slower than Eddie, but he had a lot of Eddie’s flavor.”

Shider was with the Mothership for decades and died of cancer in 2010. Check out this live version of “Cosmic Slop.” Hampton’s scorcher is first—played on his Alembic—followed by a very tasteful Shider.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)