Many bands spend an eternity waiting for their mythical day in the sun. Pentagram is among them. The group, who emerged from Arlington, Virginia, in 1971, pioneered the doom metal genre alongside Black Sabbath and was pegged to be the next big thing. But drug abuse and inner turmoil plagued the band, and their day never came.

In recent years, with the mainstream’s rediscovery of early ’70s rock, Pentagram has returned to the spotlight with more cultural capital than ever. In 2009 Jack White’s supergroup, The Dead Weather, covered Pentagram’s “Forever My Queen”—first recorded in a warehouse during the winter of 1972-’73—as the A-side of a 7" vinyl single. They included the song in concerts and performed it on TV’s Jimmy Kimmel Live!. Hank Williams III also plays the grinding love pledge onstage. And Pentagram showcased at the South by Southwest music conference in Austin and has mounted several international tours.

After the band’s plight was chronicled in Last Days Here—an award-winning 2011 documentary that focused on the drug-ravaged life of singer Bobby Liebling—Pentagram became hip in an “I-want-to-marry-Charles-Manson” way. In addition to the expected aging, bald metal dudes, everyone from PBR-drinking 20-somethings to 6-year old European toddlers are coming to Pentagram’s sold-out shows.

Sadly, a second chance at stardom hasn’t changed much for the seemingly indestructible Liebling, who continues on a 40-year habit ingesting every drug imaginable and has been at death’s door for decades. So severe is his addiction that he scratched the skin off parts of his body—leaving his limbs ravaged by gaping, open wounds—because he believed he was being eaten alive by parasites. When he’s not on the road with Pentagram, he lives on the couch of his parents’ Maryland home.

Guitarist Victor Griffin, however, has aimed for a more stable lifestyle. The man who created dropped-B tuning decades before most metal mavens even thought about twisting their tuning pegs counterclockwise, and has been dubbed the American Tony Iommi, straightened himself out by seeking salvation not from Satan but, ironically, The Man Above. Griffin maintains a clear head by partaking in many adrenaline-junkie activities. In addition to stints with various bands, including fronting the Christian heavy doom trio Place of Skulls, he’s a pro racecar driver, former semi-pro BMX rider, and runs a custom motorcycle shop out of Knoxville, Tennessee, where he lives. Since his influences go beyond metal to embrace first-generation punk outfits like the Dictators and the Dead Boys, Griffin’s playing in the current edition of Pentagram—with the rhythm section of bassist Greg Turley and drummer Pete Campbell—is also defined by a vocabulary plucked from the haunted corners of blues and rock, and a remarkably low tone achieved with modded amps.

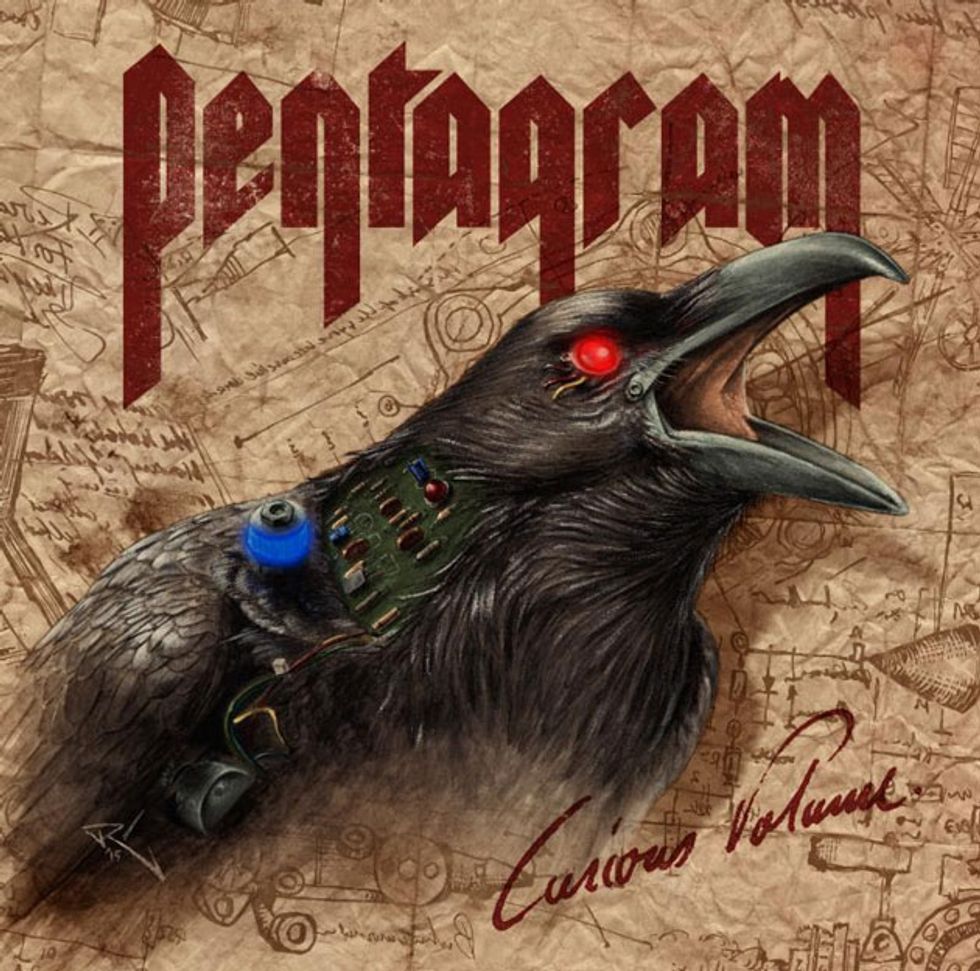

Given Liebling’s moribund state and the impossibility of actually having writing sessions, it’s no surprise that many of the selections on Pentagram’s new release, Curious Volume,had to be unearthed. Cuts like “Lay Down and Die,” “Earth Flight,” and “Sufferin’” were written way back in the ’70s.

But contrary to what you might think, Curious Volume isn’t just a perfunctory reheating of old leftovers. Many of the songs were deconstructed, then reconstructed, and given a contemporary shine. “With our style and tones, it kind of jacks everything up and they become whole new songs compared to how they were back in, say, the mid-to-late ’70s,” proclaims Griffin.

But the question remains: Is Pentagram’s day finally on the horizon?

The guitarist who created dropped-B tuning decades before most metal mavens even thought about twisting their tuning pegs counterclockwise has been dubbed the American Tony Iommi.

How did you create the dropped-B tuning?

I learned dropped D from some early Sabbath stuff. One day I was feeling creative, but also feeling kind of blocked. I sat around with my guitar and thought, “There must be another tuning besides just dropped D.” As I began to play around with the low E string, I kept down-tuning to see what would happen when I would make a fifth chord on the 6th and 5th strings. When I finally got it down to B and hit a fifth shape, it was octaves, and I’m plugged in and cranked up, and was just blown away by the thickness of it. You’re only dropped on that 6th string.

How do you keep the strings from getting too floppy with that detuned E-string?

People think that if you tune it down you have to go to heavier gauge strings, but I don’t. I use custom lights, from .009-.046. We only tune a half-step down for our standard tuning, so a .046 gauge low E-string tuned down to B is really not that bad. But you do have to play it gingerly. You can’t play it really aggressive like you would a standard tuned guitar because it will vibrate out of tune before the vibration slows down, and then it will fall back into tune. I’ve kind of cultivated my stage thing. It might look like I’m hitting it really hard onstage, but I’m not hitting that string very hard at all. The music drives you to want to play hard, but you have to restrain yourself.

Many of the songs on Curious Volume were written decades ago. Did you take creative liberties or play them verbatim, as on the original demos?

Sometimes we had to restructure a little bit. Sometimes the songs were very short. I would use the original recording enough to learn the song and everything beyond that I’d just put out of my mind and start playing as if it’s a new song. If it needs another part or an extension, I noodle around with different riffs and come up with a part that feels like it goes with that song. But I’m not necessarily trying to capture the effect that this song was written in 1970. By the time I learn a song and play it through my rig with my tone, it basically becomes a whole different animal and I can fit my new part into it based on how that song now feels to me.

“I’ve never stopped trying to cultivate my tone. I get it to different levels where it’s like, ‘This is the best I’ve had,’

but that’s not where I stay.”

How did you write with Bobby, given his precarious condition?

A lot of times we ran the ideas past Bobby, if it was his song. Sometimes he’s open to extending or restructuring the songs a little bit, depending on how much in love with the songs he is. If it’s some song that he’s just adamant about keeping exactly the way he wrote it back then, we try not to mess with that too much. We don’t want him to lose his perspective of that song.

Bobby and I write so similarly that it’s almost seamless when we put our songs together. If I come up with a new part for a song, Bobby digs it and understands where I’m coming from. If it’s a part where we decide that we could put some lyrics there as well, then he’ll write some lyrics. We try to give each other leeway and freedom. And if one guy says, “I don’t know about that,” we don’t necessarily just throw it out right away. Sometimes you have to get used to a riff. I’ve probably thrown away a million really killer riffs because I got so over-judgmental and over-analytical about my own stuff. Like, I’d think a riff was killer, then the next day I’ve played it so much that I decided that it sucks, you know?

Some of the notes of the melodic figure in the intro to “Because I Made It” seem to ring into each other, almost like a piano. Are you holding chord shapes and playing the melody through that, or fingering in a way where notes on adjacent strings briefly ring into each other?

I’m just doubling that part. I did it on two different guitars with slightly different tone settings, and it was just the way the double came out. We recorded all the guitars at [Knoxville, Tennessee’s] Lakeside Studios with [producer/engineer] Travis Wyrick, and I tell you, man, he does some stuff with tweaking knobs that just amazes me.

Often on a double like that, he’ll slide the doubled track a little bit one way or the other. And, of course, with digital recording it doesn’t even have to be the whole thing. He might just pull a few notes and slide those a little forward or a little back. I’ve called him and asked, “What was the effect you used on this? I would like to be able to get that live. Is there a pedal that I can do that with?” Right now I don’t have a setup that can do that, so if we play that song live, I’m going to have to do a bit of research because I want to be able to tweak my guitar to make it sound just like that.

The interlude of “Because I Made It” from around 1:36 to 1:50, and the outro solo from around 4:04 to 4:09 feature phrases that suggest a broader palette—beyond blues scales—that we don’t hear often from you.

Maybe [laughs]. That’s almost an enigma because I’m a self-taught player. I never had lessons and I don’t know music theory. I learned to play by ear. I listened to albums by my favorite bands and kept putting the needle back and forth, back and forth. I never felt like I was a natural. I knew guys, growing up, that would pick up a guitar and in six months, smoke. I was never that guy, man. It took me years before I would even play solos because I really didn’t have it. When I was in my teens I determined that, “Okay, if I’m not a good lead player, I’ll be a really good rhythm guitar player,” and I didn’t even know what that statement meant at the time. But I did learn much later whenever I would jam with other guitar players, there would be guys that could just burn leads but could hardly play rhythm. And you’re standing there trying to play a solo over this really bad rhythm player and, of course, it makes you look like the one that sucks.

Victor Griffin’s Gear

Guitars1991 Gibson Les Paul Standard

1987 Gibson Les Paul Standard

1994 Gibson Les Paul Standard

1984 Gibson Les Paul Studio Standard

Amps

Laney Tony Iommi Signature TI100

3 Laney GH100L heads, modded by Voodoo Amps

3 Laney GH100TI Tony Iommi signature heads, modded by Voodoo Amps (all heads have Tung-Sol EL34B power tubes)

8 Fender Showman 412S cabinets

Effects

Carl Martin Boost Kick

Way Huge Angry Troll boost

Budda Budwah

Dunlop Q-Z1 Cry Baby Q-Zone fixed wah

Mooer Ana Echo delay

TC Electronic Flashback delay

American Loopers 8-channel programmable looper

Electro-Harmonix Nano Clone Chorus

Ernie Ball volume pedal

Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2

Voodoo Lab 4-channel Amp Selector

Korg Pitchblack tuner

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL125 sets (.009-.046)

Planet Waves American Stage cables

InTune heavy picks

In the solo on “Dead Bury Dead,” at around 3:35, you repeat a melodic phrase several times, developing it along the way. It sounds like you’re almost taking a vocal approach to phrasing.

If you go back with Pentagram or any of the stuff I’ve recorded outside of Pentagram, I always do a solo to stylistically be like a vocal—like you can sing the solo. Ripping off a really fast lick is cool, too—it has its place—but all my favorite solos, growing up and still to this day, are the ones that just sing and are full of soul, where the notes hang and there are techniques like bending and vibrato.

The album’s opener, “Lay Down and Die,” features a ton of crazy wah playing in your solo. There’s a cool run where it sounds like you’re having a convulsion.

It’s almost ridiculous. It’s really completely accidental. I normally wouldn’t play the wah pedal that way. I played the solo and for some reason, man, I was having a really tense day. You know how you’ll sometimes sit besides somebody with that leg thing? Well, for some reason, I just could not keep my foot still on the wah pedal. It was just like “wah, wah, wah, wah, wah,” and I would stop and try to get my head together and calm my nerves, and I never really did get it. I kept playing through the solo—and the thing is, you don’t want to go too much. If you don’t get it within a few takes, a lot of times you start going downhill no matter how hard you try. I did a few runs, maybe four or five, and I never could stop my foot on the wah pedal. It’s a little bit tripped out. I didn’t like it at all at first, but it was the best that I had. It’s kind of grown on me now. Maybe I drank too much coffee.

Along those lines, with Bobby’s decades-long crack addiction, how does the band maintain the doomy, plodding tempos that mark Pentagram’s live sound? I’m guessing crack doesn’t necessarily lead to slow and steady.

It’s kind of funny, man, because we’ve always been considered this doom band and people describe it—especially the earlier albums—as being very doomy, dark, and slow. But if you go back and listen, even to the first album, it’s really not that slow. It’s almost like an illusion of slowness because of the heaviness of the guitar tone, the songs, and the types of riffs and chord progressions. We have a lot of medium-tempo stuff. A lot of times, it all comes down to having a good drummer—a drummer that doesn’t want to play the song to show what he’s capable of, a drummer who is satisfied with keeping the backbone of the song together. You need a drummer that is into playing this kind of music and is into playing slow, if it’s required to play slow. We have a few upbeat things, but we don’t really have a lot of fast stuff. There’s a song called “Live Free and Burn” on [1994’s] Be Forewarned that might be one of the fastest songs we’ve done. It’s about having what I call a blues-based rock drummer, not someone whose influences might be blast beats and speed metal. You can try to pull the drummer back, but a lot of times everybody has to be in the same groove, you know? We’ve played with guys that just wanted to throw blast beats in and double time things. Our music is just not that.

You’ve developed a distinctive tone that works equally well with low, bluesy riffs and high-register solos.

I’ve never stopped trying to cultivate my tone. I get it to different levels where it’s like, “This is the best I’ve had,” and then that becomes my standard. But that’s not where I stay. I continue to try to get better tone. With the low tuning and the thickness of the tone that I like, I have to play around with different pickups and things like the tone control. Depending on what part I’m playing on the guitar and where the frequency range is, I might roll the tone knob up on the guitar or I might roll it completely back.

to restrain yourself.”

So are you using the guitar’s tone control almost as an effect pedal, to shape your tone depending on whether you’re playing lead or rhythm?

Yeah, I constantly use the tone knob on the guitar. For rhythm, 80 percent of the time it’s completely rolled off with the bridge pickup, which is generally what I use unless it’s a quiet, maybe bluesier part. And then on the neck pickup, I’ll have the tone control all the way up because you’re already getting the low end just because it’s the neck pickup. And I work with that and my amp settings. I use boost pedals to push, because I don’t use any sort of distortion pedal for gain. I use the gain from the amps, because all the amps I use have a gain knob.

How do you set your amp EQs?

On a stock head of any kind, I usually run the mids pretty low, about 2 or 3. I turn the bass on 10, treble around 5 or 6, and then the presence around 5 or 6. I had my Laney amps modded by Voodoo Amps for more bass, because different rooms have different acoustics, and I would go into a room and—even though my bass was already on 10—it would feel like the sound was really thin. What I wanted was to have more headroom on the bass control.

YouTube It

Pentagram is best onstage—rippin’ it on this live version of “Forever My Queen” from Germany’s Rockpalast TV show in 2012. Check out Victor Griffin’s thick-as-molasses tone and his killer wah-drenched solo at 1:58.

How do you keep things from sounding too woofy with the bass jacked up like that?

[Laughs.] I know, I know. I tell people the bass is on 10 but it’s not woofy enough. It’s just what I hear, man. Voodoo Amps added to the bass to where I can now roll the bass back to around 6 or 7, so I have all this bass headroom. On a couple of my heads they also did a gain mod, which didn’t give me more gain, but smoothed out the gain I already had even more.

Bobby and I have been together for about 35 years, but within those 35 years I’ve really been in there for about 18, and that’s because of leaving a couple of times to go pursue other opportunities—especially back in the ’80s and ’90s when we didn’t have much opportunity. We would beat ourselves to death and we couldn’t get on the road, and had other problems along the way. It was frustrating being stagnant. The thing is, Bobby and I always had a pretty good relationship. Our songwriting, like I said before, meshes together, and we perform well together. We both made these life commitments to music and at this point, in our 50s and 60s, we need to do what works best regardless of the circumstances or the situation. Bobby and I do better together than we do apart.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)