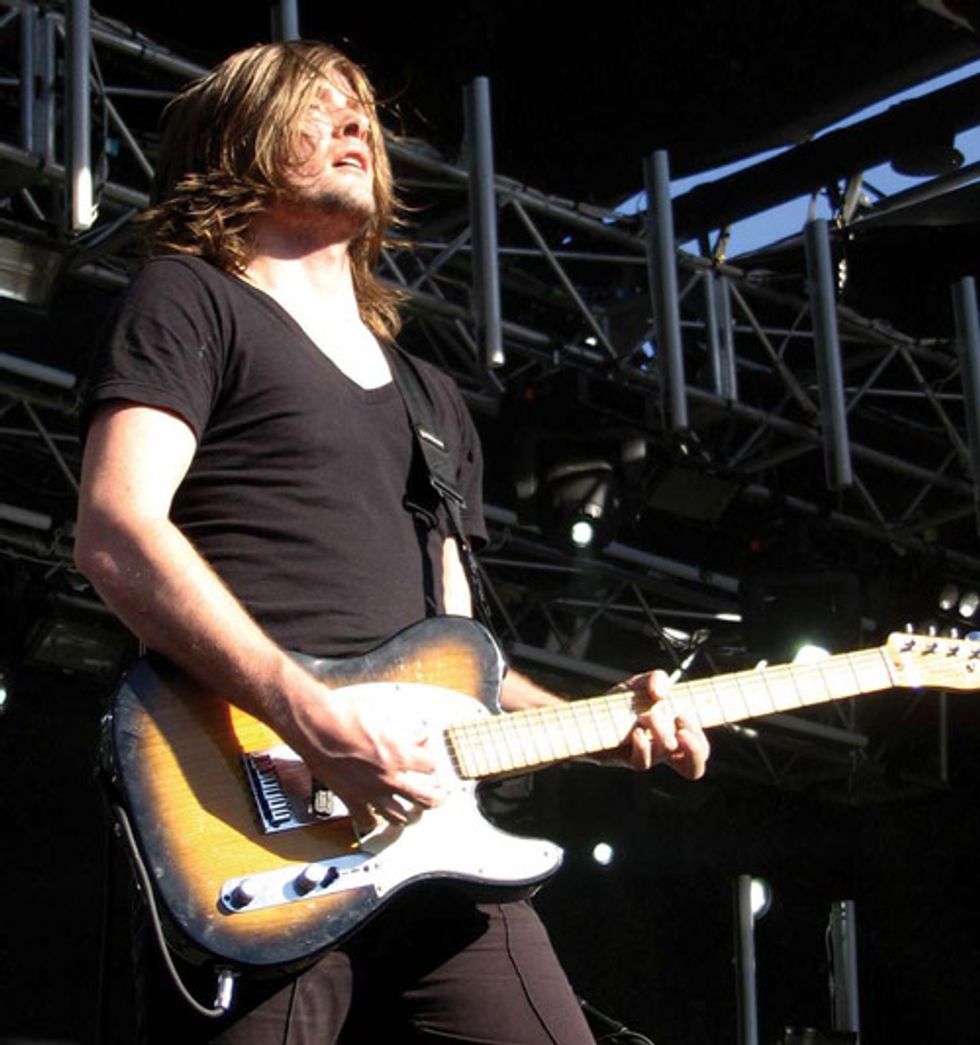

Thursday’s Tom Keeley (left) and Steve Pedulla onstage with their guitars of choice—Fender American

Standard Telecasters with Seymour Duncan Hot Rails bridge pickups. Photo by Dave Summers

Since emerging from the late-’90s hardcore underground and achieving wide acclaim, Thursday has been credited with helping pave the way for modern-rock heavyweights like My Chemical Romance, exposing the world to great new hardcore bands via the opening slots on their tours, and maintaining street cred by recording with up-and-coming bands like Japan’s Envy. More than anything though, Thursday will be remembered for defining the emo/post-hardcore blueprint via Steve Pedulla and Tom Keeley’s scintillating dual-guitar attack, Geoff Rickly’s passionate singing and open-hearted lyrics, and the utterly dominating rhythm section of bassist Tim Payne and drummer Tucker Rule.

Indulging in extreme dynamics while melody battles discordance is Pedulla and Keeley’s raison d’être. This juxtaposition was first explored on the band’s second album, Full Collapse—which they have been recently performing in its entirety to celebrate its 10-year anniversary. Thursday’s major-label debut, War All the Time expanded on the sound with a keener sense of eloquence as pianos and choirs found their way into the oft-ferocious mix. The band’s 2009 release, Common Existence, showed a conscious shift away from the post-hardcore constraints they helped establish, and now their sixth album, No Devoluci—n, finds them exploring deep valleys and high peaks—be they emotional or melodic, expressed in subtler or more intriguing ways.

“There are traditional chord structures in things we do,” explains Keeley, “but there was sort of an effort to circumvent the guitar or approach guitar parts other than thinking of them as guitar parts—kind of undoing the guitar as a traditional rock instrument and using these different effects, chord structures, and strumming patterns to make a more nebulous, melodic vehicle.”

As Pedulla puts it, “A big part of what makes us Thursday is that there are sometimes parts that are almost two leads going on, and they interlock in some strange or unconventional way—so there’s definitely a different dynamic to how we write. It’s the type of thing where both of us will be vamping on a part to try and find what we’re going to play, and we sort of have this unspoken rule where we say, ‘Right . . . bear with me. I’m going to fall on my face a lot—but I will find something.’ We have that trust. We know we’re not being judged by each other.”

Keeley agrees. “It’s a million different things—it’s never the same equation twice. Sometimes we just ignore each other and play as many notes as possible. Sometimes we dictate to each other. I think it’s safe to say there’s a mutual respect for our different points of view and different practices of guitar playing. I couldn’t imagine these songs without Steve’s unique voice. It’s a weird alchemy, a weird experiment. There are a lot of mistakes, a lot of revisions, and tons and tons of editing, historically anyway. And, eventually, even if our parts are fighting each other, we know when it’s working and we know when it’s not.”

Pedulla reaches to the nether regions of his Tele’s fretboard. Photo by Elise Shively

As far as “nebulous melodic vehicles” are concerned, it’d be hard to argue that Keeley and Pedulla have been anything but successful on that front with No Devoluci—n. Written in the wake of Rickly’s divorce, it has an emotional rawness set to churning fury, chiming elegance, and wreaths of eclectic treatments.

“But the whole record isn’t that,” Keeley is quick to add. “It’s not like our guitars sound like ghosts or anything! We certainly have a lot of power chords and traditional angular guitar work—which is sort of our thing. In that sense, it was business as usual. But with [producer] Dave Fridmann, there’s a lot of attention to pushing things toward the weird.”

Fridmann has produced Thursday’s last three records, but reportedly it was the latest one—which was barely demoed at all and was written in just a week—that particularly fired his imagination. What is it about Fridmann that keeps the band coming back to him for production duties?

“You rely on Dave to tell you when to cut the shit, quit thinking, and just play,” says Keeley. “But if I say to him ‘Hey, man, I don’t know if this part is right for this record—how does this sound?’ he’ll reply ‘It sounds like a guitar.’ That means it’s my responsibility to dial in exactly what I need. In the past, I’ve gone, ‘I’ve got no idea what guitar tone I want— what do you think would be a good idea?’ to other producers, and they’ll come up with all these suggestions. Dave does do this on occasion— he’ll fine-tune things—but generally it’s ‘What do you want it to sound like? What’s your vision?’ That’s scary, but ultimately it forces us to become better musicians with better ears. He generally trusts our gut and our instincts, as far as getting into the weird spots. It’s terrifying—but completely empowering.”

For a band of self-described non-musicians, Thursday encompasses a scope and spectrum of aural possibility that’s perhaps wider than musicians who play “by the rules.” Thursday’s distinct sound has always revolved around Pedulla’s and Keeley’s clashing tones. Clean melodies run parallel to each other before soaring through molten distortion, generally grappling with each other and causing semitone clashes, off-kilter countermelodies, and ending in all sorts of pleasing chaos. You expect dropped-D tunings, escalating octave melodies, furious tremolo picking alongside thrashed minor 7th chords, and, more often than not, the delight of crashing from clean, intricate chords to full-tilt, metal-tinged riffs. Light chorus and a splash of delay keep the flashier melodies sounding like they’ll float into forever, but it’s the stop-start breakdowns punctuated by complete silence that define Thursday’s guitar MO.

Devolving the Guitar

For No Devoluci—n, Thursday’s guitar team endeavored to unlearn the guitar—to almost completely deprogram their whole style, only occasionally bringing in their familiar melodic impalement. “Not every song has that,” Pedulla says, “but we really like to have a wide dynamic range in terms of getting real quiet and clean—and then really heavy. It’s a keystone of what we do, for sure. A good example is on the last song on the record, ‘Stay True.’ It does the same thing but in a completely different way.”

The song in question begins with an electric guitar that’s so gently picked it’s almost imperceptible. The drums enter, followed closely by a flood of EBowed feedback in the background. There’s a tension that sits underneath the calm and, three minutes into the seven-minute epic, Rickly’s voice becomes histrionic and the guitars build up along with the pummeling drums. Though it never reaches the abrasive levels of previous material, there’s a simmering darkness that never would’ve come across in the vicious heaviness of their older material.

Pedulla and Keeley are happy to discuss some of their favorite guitar moments on No Devoluci—n, as well as how they managed to get some of the more out-there sounds on the record. The first track, “Fast to the End”, has a wild noise solo—a warped, Tom Morello-esque skittering across fluctuating pitches. “It was a lot of fun to do—and I’m actually wondering how I’m going to recreate it live—but I know I’ll figure it out,” Pedulla says. “I had set up various filter and modulation settings on one of those Line 6 M13s, and I also put some parameters into the expression pedal to control each one. So I would hit a chord and switch back and forth between the different settings and also work the expression pedal. On some of the takes, I wasn’t even aware of the guitar—I would have it on the floor, hit the note, and then just play the pedals with my hands and kind of go for it. We started to realize that when you go to this effect, it does this thing and that’s a good opening, and then when you go to this, that’s a great mid section, and this is a good closing. So it was almost directed improv.”

In comparison, Keeley contributes a beautiful, slightly atonal melody to the skeletal and haunting ballad of loss, “Empty Glass.” But while the duo envisioned the type of vibe you hear on the album, the way they got it was actually a mistake.

Keeley (left) engages his bridge pickup and barres high on the neck as Thursday’s

keyboardist, Andrew Everding, strums . . . you guessed it—a Telecaster with a Duncan

Hot Rails bridge pickup. Photo by Elise Shively

“We recorded it during the last session,” says Keeley. “Geoff had the vocal part and the Hammond organ part and not much else. We knew we needed to finish it, so it fell on me to make the glitchy instrumental sections. I was really excited about that, but it was very frustrating to make, too. It ended up as a clean guitar run through a reverb pedal and a Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler. Instead of strumming, I just turned the reverb and gain up and fretted the string with my strumming-hand finger. With all that sustain, I was able to play the guitar more like a violin. There were six layers of the main progression and six layers of harmonies, and that was going to be the part—this forward-moving thing. But then I accidentally stepped on the DL4’s loop reverse-play button, and it was suddenly a more powerful piece in reverse—with these suspended melodies and a weird timing that pulls you along in this uncertain way. The sweet note of the progression is delayed just a little bit too much, and at first I was like ‘Ah man, I wish I’d taken that one set of four beats out so it hit right where I wanted.’ But everyone was like, ‘Dude, you’ve gotta leave it—that’s what’s going to really engage people and make them listen more intently.’” Keeley adds that, if it hadn’t been for Fridmann’s “writing doesn’t end until the mix is over” ethos, there wouldn’t have been nearly as many spontaneous moments like that.

But as Keeley previously mentioned, No Devoluci—n isn’t all abstract soundscapes. The whiplash switch-ups and intense guitar buildups that have kept Thursday fans enthralled throughout the band’s existence manifest themselves in the savage shift from seething fuzz to all-out saturation on “Past and Future Ruins.” But even that has evolved.

“The chorus riff has a swing to it that we haven’t had before. To expose myself a little bit, it was my attempt at making a Silversun Pickups song,” Keeley confesses with a laugh. “I don’t think it sounds anything like them, though—which is usually the story with me: If I have a favorite band and I try to write something like them, I’m usually not good enough to nail it, y’know?”

Gear Simplicity

Despite the number of textures and deceptively intricate ideas throughout Thursday’s back catalog, Pedulla and Keeley have pretty simple rigs. The latter tends to favor Marshall and Vox AC30 amps and standard Fender Telecasters with a Seymour Duncan Hot Rails bridge pickup. Pedulla is a bit more adventurous in his use of multiple effects units, but he also favors Telecasters with a Hot Rails bridge unit. He also has a custom First Act hollowbody—which is also stocked with Hot Rails.

“For some people, that’s a weird pairing— to put that hot of a pickup in a guitar like that,” he says of the double-cutaway, Bigsby-outfitted guitar. “But it’s awesome, and that got used probably the most. “Dave also has an awesome Harmony Rocket that we used, and I have a Jaguar that I played on a couple of things.”

Amp-wise, Pedulla has recently gotten into Bad Cats. “I used to use the Bogner Ecstasy Classic for distortion and I tried various combos for clean sounds, but I just got myself a Bad Cat Lynx and that’s all I use now. The second day of the tour, our front-of-house engineer came up and was, like, ‘Dude, that is the best your guitar has ever sounded!’ And I feel the same way. For the first recording session, I really wanted that Bad Cat but I didn’t have one, so I borrowed one. After two weeks or a month off, it became a challenge to find one for the next session. Dave was pretty adamant too—‘You need to make sure you have that amp again.’ Luckily, a friend of mine had an extra one he sold me at an amazing deal. So that and the Line 6 M13—that’s all I need. The only thing I use in the studio that I don’t have in my live rig, at least for now, is a DigiTech TimeBender Digital Delay pedal, which is a lot of fun.”

Keeley, on the other hand, had some difficulties with gear during the No Devoluci—n sessions. “When we went into the studio, a lot of my gear was in disrepair,” he says. “So the biggest change for me was, ‘Steve, can I play your guitar here?’ and ‘Oh, this doesn’t work—but it sounds kinda cool.’ It was a hodgepodge of amps that did or didn’t work or were blown or wires that were disconnected. It’s definitely strange making something that’s going to last forever in a context where you’re not confident in what you’re using. It’s impossible for that not to affect what you play, as well as the energy of the parts. It can add to the tension of a part or a song or just the energy of a record. I can hear things like that, at least in my own playing.”

Keeley sees the light live. Photo by Louise Lockhart

He missed one amp more than anything else. “There’s a Marhsall JCM900. It’s Geoff’s amp, but it’s the one I played in the basement days for years and years. It has been historically troublesome and finicky, but it sounds fantastic. Beyond that, the most frustrating thing was that I have a couple of AC30s that sound fantastic, but the noise . . . we couldn’t get rid of it no matter what we did! That was a daily struggle.”

Home Is Where the Hardcore Is

What separates Thursday from some of the more dubious exponents of the genre they helped create is their willingness to embrace newcomers and their steadfast refusal to turn their back on the hardcore scenes they grew up in. Whether it’s offering opening slots to recent up-and-comers Touché Amoré and La Dispute on tour or Pedulla revealing that studio communication often involves requests such as, “Play something like an old Quicksand drum beat,” the guys in Thursday continue to have a hand in the DIY scenes that made them who they are today.

“It’s a school of thought we were exposed to at a young age, and it became an inherent part of our personalities and our philosophy for life,” Keeley says. “Be authentic, don’t sell people on an idea. Rather than selling people on an idea, present them with a piece of art and allow them to take it from you and accept or reject it—and be okay with that.”

And No Devoluci—n is indeed a piece of art—arguably with more emotion, innovation, and hardcore attitude than anything Thursday has done before. All without returning to what they’ve done before—and all without turning their back on it, either.

LEFT: Keeley’s Marshall-and-Vox amp rig backstage before a show. The Bogner head belongs to Thursday’s keyboardist, Andrew Everding, who occasionally plays rhythm guitar during live shows. Photo by Clive Patrique RIGHT: Effects-wise, Keeley keeps things quite simple—he stomps on a Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, a Lehle Dual amp switcher, a Fulltone OCD, and (not pictured) a Boss TU-2 Tuner. Photo by Clive Patrique

|

Guitars

Fender American Standard Telecasters with maple fretboards and Seymour Duncan Hot Rails bridge pickups

Amps

Marshall JCM800, Marshall 1960 AV slant Cab, Vox AC30 Hand- Wired reissue

Effects

Fulltone OCD distortion, Lehle Dual amp switcher, Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, Boss TU-2 Tuner

Miscellaneous

DR Strings (.010, .013, .017, .030, .044, .052), Dunlop .60 mm Tortex picks, Mogami cables with Neutrik plugs, Line 6 Relay G50 wireless

|

Guitars

Fender American Standard Telecaster with a rosewood fretboard and a Seymour Duncan Hot Rails bridge pickup

Amps

Bad Cat Lynx head, Bogner 4x12 with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Line 6 M13 Stompbox Modeler, Line 6 EX-1 Expression Pedal, Voodoo Lab Pedal Switcher, Voodoo Lab Ground Control Pro MIDI foot controller, Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus, Boss TU-2 Tuner

Miscellaneous

DR Strings (.010, .013, .017, .030, .044, .052), Dunlop .60 mm Tortex picks, Mogami cables with Neutrik plugs, Line 6 Relay G50 wireless

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)