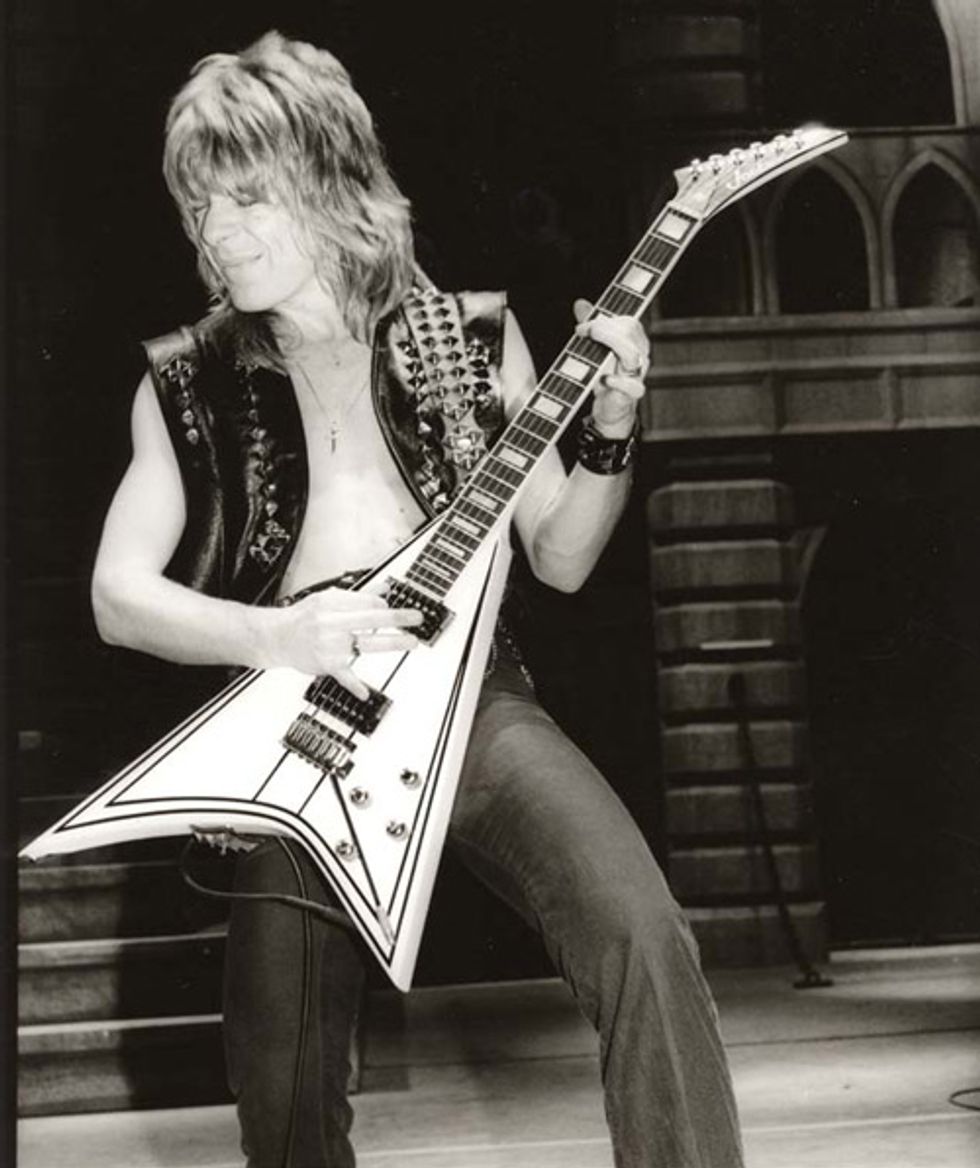

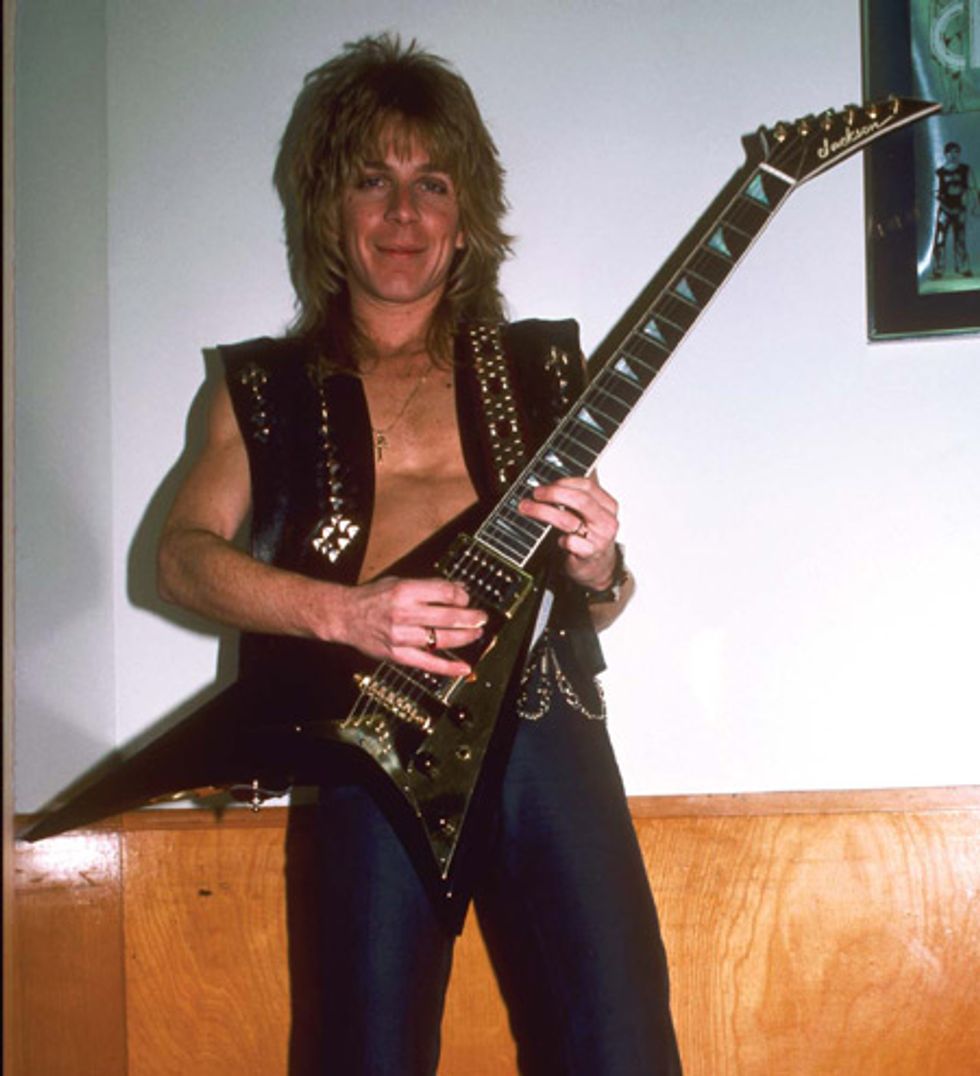

Randy Rhoads and his original Jackson Concorde V at a dress rehearsal for the

Blizzard of Ozz tour at Zoetrope Studio in late 1981.

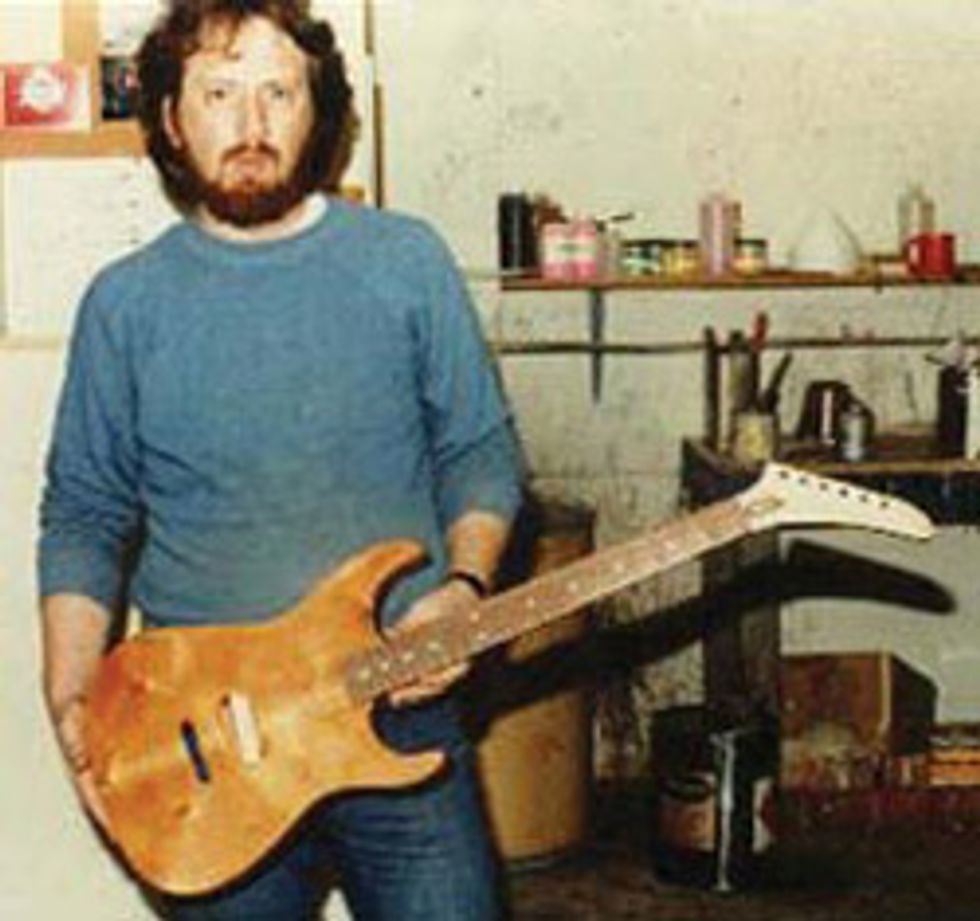

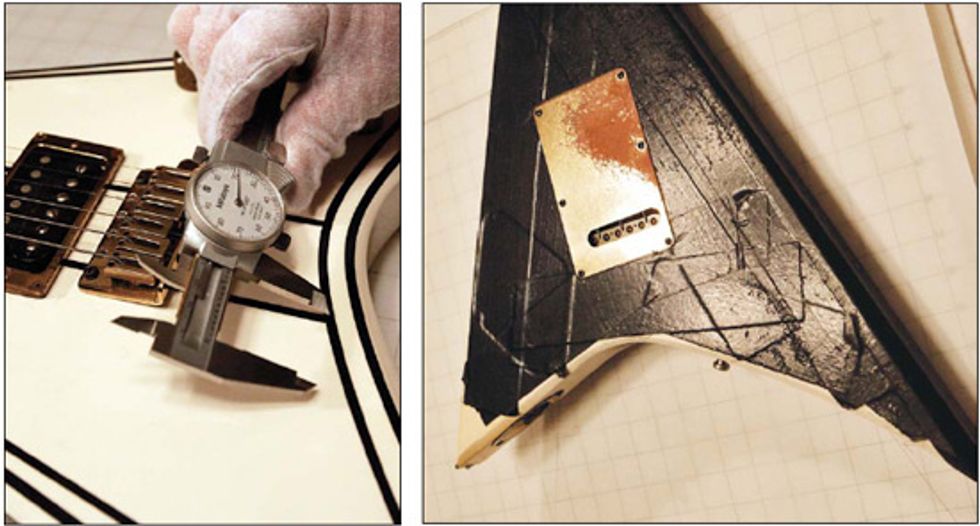

Left: Mike Shannon and Chip Ellis measuring the Concorde V at Delores Rhoads’ Musonia School of Music in North Hollywood in 2009. Right: A young Shannon with Rhoads’ second Concorde V in November 1981.

Although things really started to happen for Grover Jackson after he bought Charvel’s Guitar Repair from Wayne Charvel in 1978—not long after Edward Van Halen had spearheaded a new era in hard rock with his “Frankenstein” guitar built from a Charvel neck and body—the rise of the Jackson brand can be traced back to a disposable napkin.

In 1980, a young guitarist named Randy Rhoads contacted Jackson with the hopes of having a guitar built for him based on the sketches he’d made on a thin, flimsy square of paper snagged from some long-forgotten dining table. The instrument’s name and shape were unique in that they derived from his preferred mode of travel to and from Europe—the Concorde supersonic airliner. Soon thereafter, Jackson and Rhoads went to work creating one of the most distinctive guitars in history. With its offset V shape, streamlined body, and neck-through construction, Rhoads’ Concorde turned a lot of heads— and the guitars based on that design continue to do so today. The Concorde became the first official Jackson model, the beginning of a respected and iconic brand that has lasted for more than 25 years now.

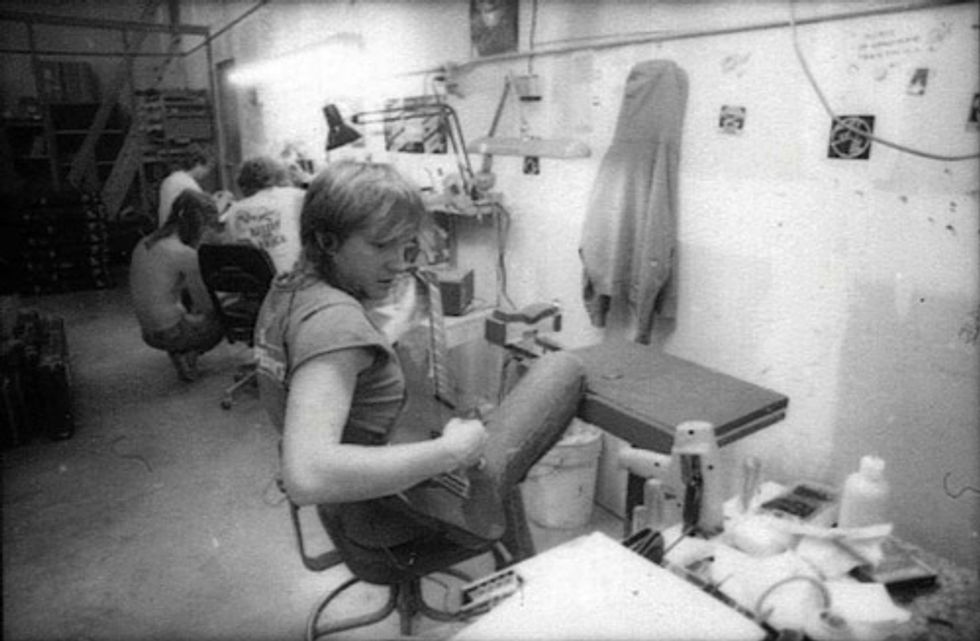

Master Builder Mike Shannon was there at the beginning. He worked alongside Jackson, building and designing some of the most acclaimed instruments to bear the Charvel and Jackson name. In fact, after Rhoads toured with the first custom V for a while, Shannon built the second Concorde for him.

The whole Charvel/Jackson gang in 1983. Mike Shannon is second from the right

in the front row, and Grover Jackson is fourth from the right in the back row.

Jackson’s Mike Eldred testing at the Charvel/Jackson shop in San Dimas in 1982.

A Kahler-equipped Kelly formerly used by Sammy Hagar.

When Fender acquired Charvel and Jackson in 2003, he was promoted to Senior Master Builder for Jackson. Today, he maintains the same high standards and absolutely freakish attention to detail that he learned as a teenager from Grover Jackson in the early ’80s. And he’s still surrounded by many old friends from the original Charvel/Jackson crew, which the company says makes Jackson the longest-running custom shop in the United States.

We recently visited the Jackson shop to talk with Shannon about his storied history with the company and take a look at the many cool projects going on there.

What were you doing before you joined Charvel?

I was working with a furniture company. I’ve always been into making things. I knew woodworking, and even in high school I had a part-time job helping this guy do fine furniture. I learned about exotic woods and a little bit about tools. This was a summer job, probably around 1977.

How did you meet Grover Jackson?

set-neck early prototype of what would become the Soloist. |

What was the guitar line like back then?

We were basically making Strat[-style] bodies with the one humbucker in the bridge. There weren’t a lot of guitar parts at the time: You had hard-tail bridges, the brass trem bridge, or Tune-o-matics. Our work orders at the time were on three-by-five cards with handwritten work-order numbers. That’s all we had to build from, just handwritten information. This is pre-computer stuff.

Who were your clients at the time?

There were local players, but most of them were up-and-coming musicians. Gary Moore was one of the super-early guys. After Eddie Van Halen got the striped guitar, that put Charvel on the map. We were the original hot-rod shop. We would change pickups and repaint things in the early days. We started building our own bodies. We’d cut down a Strat[-type] template and turn it into a Dinky model. And if you took an Explorer body and chopped out the bottom end, that was the birth of the star shape, which goes back to 1979.

How did Randy Rhoads come to Charvel?

I don’t really know the details about how Randy knew about us, but Grover used to go to Hollywood and hang out at the nightclubs to get to know people. He came from a background of being a guitar player and working with Anvil cases. He knew a lot of people in the industry who had started Mighty Mite and some of these other guitar companies that were doing parts and stuff like that. He was in touch with everybody.

A rare shot of Rhoads playing his second Jackson Concorde V backstage before a December 30,

1981, gig with Ozzy Osbourne at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. Photo by Neil Zlozower

What do you think made the company stand out at that point in time?

There were a lot of young people, and we were all into quality. The detail and the quality, at the time, would surpass any other company. We were all anal about the detail and the fit and finish. If you build bad stuff, you’re not going to be around long.

Tell me about the Randy Rhoads model.

I worked on the black Rhoads model with the brass parts. I remember it being one of the first neck-through-body things we built. We glued up five chunks—which were 3/4" to an inch wide—for the center blank. For the butt of the neck, you only need around 2 1/4". The last two pieces that were glued on those were basically scrap. Later on, we just used three pieces down the center and then glued the wings on. The black Rhoads was also the first guitar we put headstock binding on. I believe there was a neck-through-body Star that had been built prior to Randy’s, although it didn’t get any recognition or the Jackson logo. I believe it had an Explorer[-style] headstock.

What were the other differences between the first Rhoads model and the second one that you built?

The white Concorde is made out of Pacific Coast maple, which is fairly light. When I picked up Randy’s first guitar during our inspection and measured it, it wasn’t as heavy as rock maple. The two-piece center blank has the same Pacific Coast maple sides. The black one has a five-piece rock maple center blank, which is fairly heavy. We used poplar wood for the sides. As far as the neck shapes go, the white one was pretty thick and round. Randy liked the Les Paul feel. On the second one, it was more of a D shape. Randy told Grover later on that he didn’t like the D shape. He liked the round shape. We started four more guitars for him, but unfortunately he passed away before those were done.

A bevy of exotic custom Jacksons in various stages of finishing.

Jackson Master Builder Pablo Santana’s workbench features the signatures of various employees

over the years. On it are routing templates for control cavities of different Jackson models.

What was the reasoning behind the second guitar having a D-profile neck? Did Randy request it and then change his mind about it?

On the second one, we didn’t have the specs so we made it kind of like a standard Jackson style—which is a little thinner. At the time, we didn’t know he preferred the Les Paul-style shape. We were trying to get the body shape correct, and the neck wasn’t a big question at the time.

Were the rock maple and the poplar wings on the second Concorde one of Randy’s requests?

Again that’s another really tough question for me. That’s how we started making neck-through-body guitars as a standard model. I think it was due to weight and cost of materials at the time.

What can you tell us about what was actually on that first sketch napkin?

It was more about the flying-V shape that he had wanted, along with some bow-tie inlay sketches.

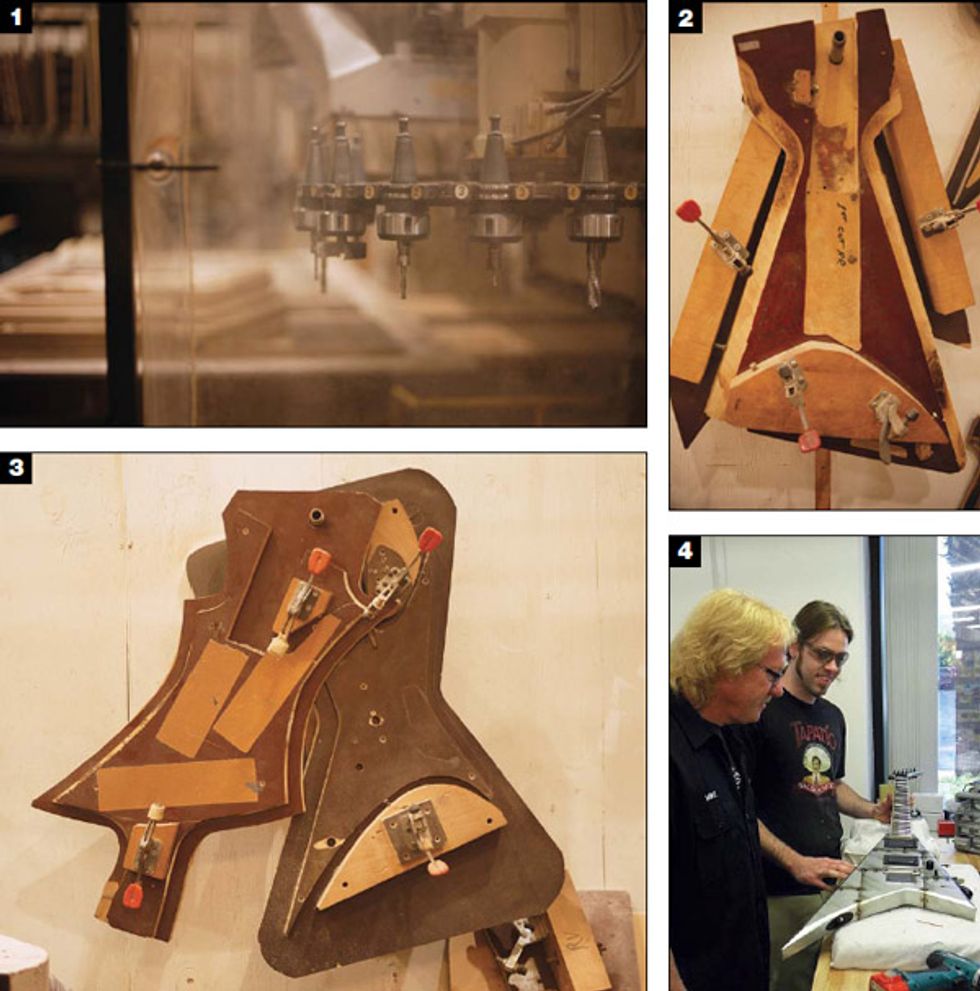

1. An old CNC tool carousel still in use at the Jackson Custom Shop. 2. The body-route template for the original Randy Rhoads guitar. 3. Body-shaping templates for a Kelly (left) and a Warrior. 4. Mike Shannon (left) and tune tester Joe Williams worker inspect an RR 24 Rhoads with a welded-steel-themed custom paint job.

Was he particular about qualities he wanted in the pickups, controls, woods, hardware, or other ergonomic considerations?

I’m sure he was, but I didn’t really get to know him as well as other people. I know he was really particular. He had an accident with the white one where he made a little chip on the wing. He brought it back into repair and he was nearly in tears—he felt super bad. We did a repair on it and he felt better.

What is known about the pickups used in the first two Concordes—were they pretty much vintage PAFs?

I believe they were Duncans but I forget the numbers.

How do those guitars compare with the current Rhoads model?

The main differences are the front control plate and the string plate. We don’t typically use the Tune-o-matic[-style] bridge anymore. That was a bridge made by a local guy here in Orange County. The front control pocket today is a little bit smaller than what is on the original Rhoads, and our shark-fin inlays are larger. On Randy’s original model, he had binding over the frets—the frets are installed and filed flush to the edge of the fretboard. Then the binding is put on and all filed out between the frets. Today, we have notched frets—we put the inlays and binding on, and then press the frets to where they overlap the top of the binding. In special-order cases, the customer can still buy the binding over the frets.

Did you ever meet Randy?

Just briefly as he went through our mill doing a walkthrough with Grover. Most of the times he came in, it was after hours. Being a rock star, he probably didn’t get up until four in the afternoon. He seemed like a real nice, quiet kid. He was older than me at the time, but we were all kids. Grover described him as a really nice, reasonable kid.

Sean Silas (left) and Joe Williams at their final-assemply stations. Photo by Oscar Jordan

A pin router with a custom Soloist in progress. Photo by Oscar Jordan

One of the latest prototypes for Megadeth guitarist Chris Broderick along with one of the body-shape

drawings its based on. It’s routed for a 3-way toggle in the forwardmost position, followed

by a Volume knob, a Tone knob, and a coil-tap switch. Photo by Oscar Jordan

A USA SL2H Soloist with a mahogany body and neck-through design topped with green-stained

quilted maple. Hardware includes Duncan JB TB-4 (bridge) and JB (neck) humbuckers, a

3-way toggle, and Volume and Tone knobs.

Who where some of the other clients wanting custom guitars back then?

I remember guys like Chris Holmes from W.A.S.P. coming in. Warren DeMartini from Ratt came in a bunch of times. Robbin Crosby [also from Ratt] would come in. Robbin had the King V, but he also had the Firebird[-style] stuff. We had Jake E. Lee and Jeff Beck, as well.

What came after the Rhoads model?

Back when metal was exploding, the Rhoads was so appealing. It started out with the Rhoads, then the Soloist, the Kelly, and then the King V. After that, the Warrior came along.

Why did the company change the name and logo from Charvel to Jackson?

Jackson didn’t want to call these guitars Charvel because they were nothing like a Charvel. Charvels are basically bolt-ons and are more similar to Fenders, so Jackson only made sense.

The headstock of Rhoads’ original Jackson Concorde V. Note the early version of the Jackson logo.

Left: Shannon uses gauged calipers to ensure every aspect of the Rhoads Tribute Relic is true to the original.

Right: Few get to see the other side of Rhoads’ original Concorde V. The legendary guitarist treasured

the guitar so much that he covered the back in layers of tape to protect the finish. Evidently, he was far

less worried about buckle rash on the trem-cavity plate.

The original Concorde V next to Shannon’s copious notes and a studded

leather strap that very well may outweight the guitar itself.

What distinguishes Jackson from other custom builders?

The guitar player will get what he wants instead of what the store will sell him. You have the choice of pickups, fretwire, binding, colors, and odd-shaped necks.

Tell me more about the “odd-shaped necks.”

The earliest Charvel necks were pretty thick and round. Later on, they just started getting thinner and thinner—in some necks, we’ve sanded through the back and hit the truss rod. The speed metal guys like them that way. But the neck shape is the player’s choice. We’ve done boat shapes, V shapes. Recently we’ve even made some guitars with off-center back shapes. Under the low-E string, the back is thicker than on the high-E side, which would be really thin to facilitate easier leads. We’ve done some strange ergonomic back shapes.

All of these things turn our guitars into really personal pieces. You can pick up 30 guitars, but guitar players always know when that certain guitar is right for them. We have a very good batting average of building guitars for people and, when they get them, they’re really happy.

Although Rhoads was often photographed with his first Concorde V, some players may be surprised to

learn it has a 3-way pickup selector that was usually out of view in concert photos. Shannon isn’t

certain whether Rhoads made specific electronics requests, but the Tribute Relic features Duncan

SH4 (bridge) and SH-2N humbuckers and Les Paul-style controls.

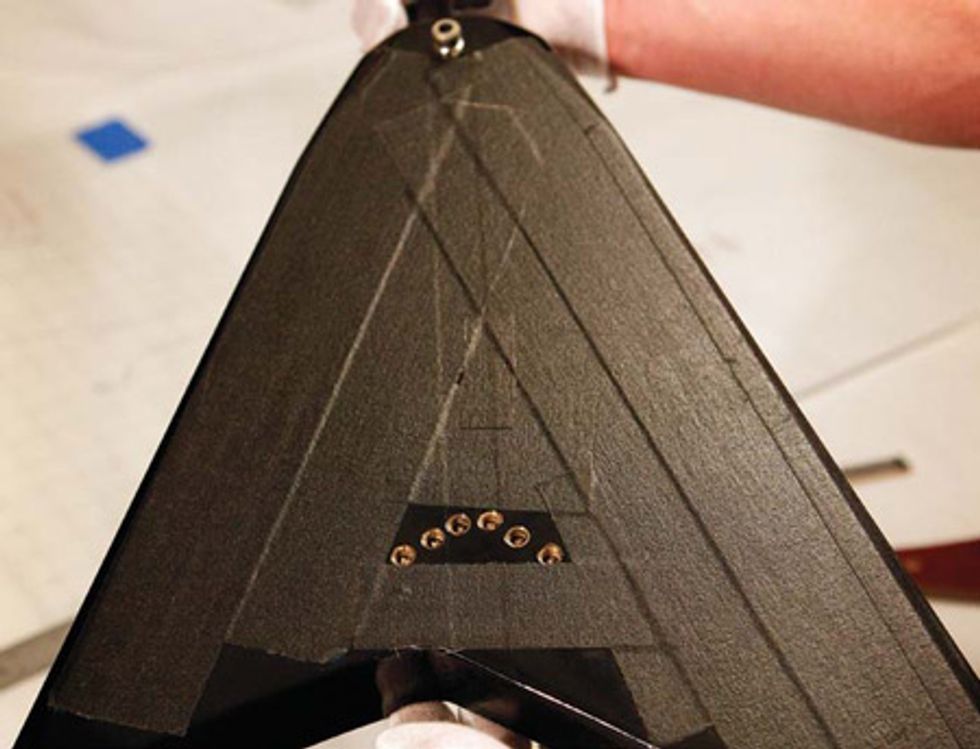

Rhoads’ second Concorde V had several departures from the original, including string-throughbody

construction, a D-profile neck, a brass pickguard, a front-mounted pickup selector, and a Master

Volume instead of Volumes for each pickup.

Rhoads only had the second Concorde V for a few months before his untimely death,

thus the relatively unscathed tape on back.

Megadeth Bassist David Ellefson Talks About Defining Metal Tone with His First Jackson 5-String

David Ellefson playing live with his signature Custom

Shop Concert Bass. Photo by “Iron” Mike Savoia

You and Jackson go way back, right?

|

What makes the tones from those basses unique?

The tone had a lot of top end, so I could get up and really click along with the trigger sound of the drums. It had a lot of bottom end and wallop in the bass notes. I scooped a lot of my mids out, because that’s where all the guitars were. The midrange became the domain for the guitars, so the Jackson bass with a lot of bottom and a real high top gave me a great EQ position in the overall Megadeth sound.

What’s the difference between the modified Concert Bass they made for you and your current signature model?

|

What sort of woods is it made of?

It’s an all-maple neck-through with alder body wings. We left the back of the neck unpainted, so it has a soft, satin kind of finish on it. It has a very natural wood feel to it rather than being lacquered or painted.

What was it like working with Mike Shannon?

Mike made most of my basses years ago, so he knows the history. Mike is a guru in the woodshop. He’s got a feel for instruments—he knows how to make instruments that players like. There’s a lot of great wood guys and there’s a lot of great technician guys. To get a guy who can pull all that together, and make an instrument that sits in a player’s hands, is a whole other art.

Megadeth’s Chris Broderick Discusses His New Jackson 6- and 7-String Signature Guitars

Chris Broderick onstage with a Jackson Custom Shop signature prototype that’s simultaneously futuristic and elegant looking, thanks to its subtly carved, flamed-maple top with a semi-transparent finish that complements the black binding and white, body-mounted humbuckers.

How did you decide to take your signature guitar ideas to the guys at Jackson?

I talked to a number of other companies and Jackson was really willing to step up to the plate and build me the guitar that I envisioned. It was the idea that there was no compromise in not only what they would build for me, but also what they would offer to the public.

What do you mean?

Stainless-steel frets are a big issue for a lot of builders. With Jackson, it was no problem. And Jackson really stepped it up on the 7-string guitar—they were able to get with Floyd Rose and build the first ever 7-string, low-profile version of the Floyd Rose tremolo. That, to me, is phenomenal!

What other features did you want?

I really like a 12" fretboard radius all the way across. They were able to do that when other companies just wanted me to pick out a model they already had and slap my name on it. I also love the asymmetrical offset body. I’ve always been a fan of that, which is why I designed it that way. It also serves a very ergonomic function: It takes the balance of the guitar and makes it so that you can angle the neck up. The neck doesn’t want to drop down like on other guitars. That was a huge plus for me.

We looked at everything from the lower horn cutaway and the upper horn cutaway, and those relief cuts that are on each side. Then the placement of the Volume and Tone controls, the jack for plugging in the guitar cable, and how ergonomically that fits in. Also, how the guitar sits against you, and what angle it juts out at. We looked at a lot of things in terms of its playability.

Are your new guitars pretty light or do you like them fairly substantial?

My guitars are fairly heavy, but that’s mainly because I like dense wood. It’s a fairly typical combination of mahogany and a plain maple top. The quality of the wood that Jackson has is unbelievable. I would love to play a guitar that’s half a pound if you could make it, but I have a feeling it wouldn’t sound that good, tonally. The weight of the guitar is based more on the quality of the tone than how comfortable it is to wear.

What was it like working with Mike Shannon?

He was absolutely horrible! [Laughs.] No, he’s awesome. He’s so meticulous about getting things right and making sure they’re exact. The detail work that he does with everything is so precise. I’ve never seen work of that quality before. When he takes on a project, he makes it personal.