Digital recording has been a boon to music in innumerable and immeasurable ways. And the ubiquity of hi-tech devices in our daily lives today—as well as the incredible rate at which sophisticated features trickle down to the masses—has only compounded the effect. Today, it’s affordable and remarkably convenient for just about anyone to make high-quality recordings on the run, in home project studios, and at rehearsals and gigs.

But while the possibilities are nearly endless with this new technology, that doesn’t mean creating a great recording is simply a matter of having a kick-butt computer, smartphone, or dedicated recorder. Technology only gets you so far. Now, more than ever, you have to know what you’re doing to get great results—because it’s just as easy to make a bad digital recording as it is to make a bad analog recording.

To that end, we’ve compiled this list of 10 must-know tips for digital recordists to keep in mind no matter what platform or interface you’re using. Armed with this knowledge, your guitars, your platform of choice, and an impeccable set of ears, you’ll soon be cranking out digital recordings that are clean, clear, fat, full, and ready to capture the hearts and minds of listeners everywhere. Let’s dive in!

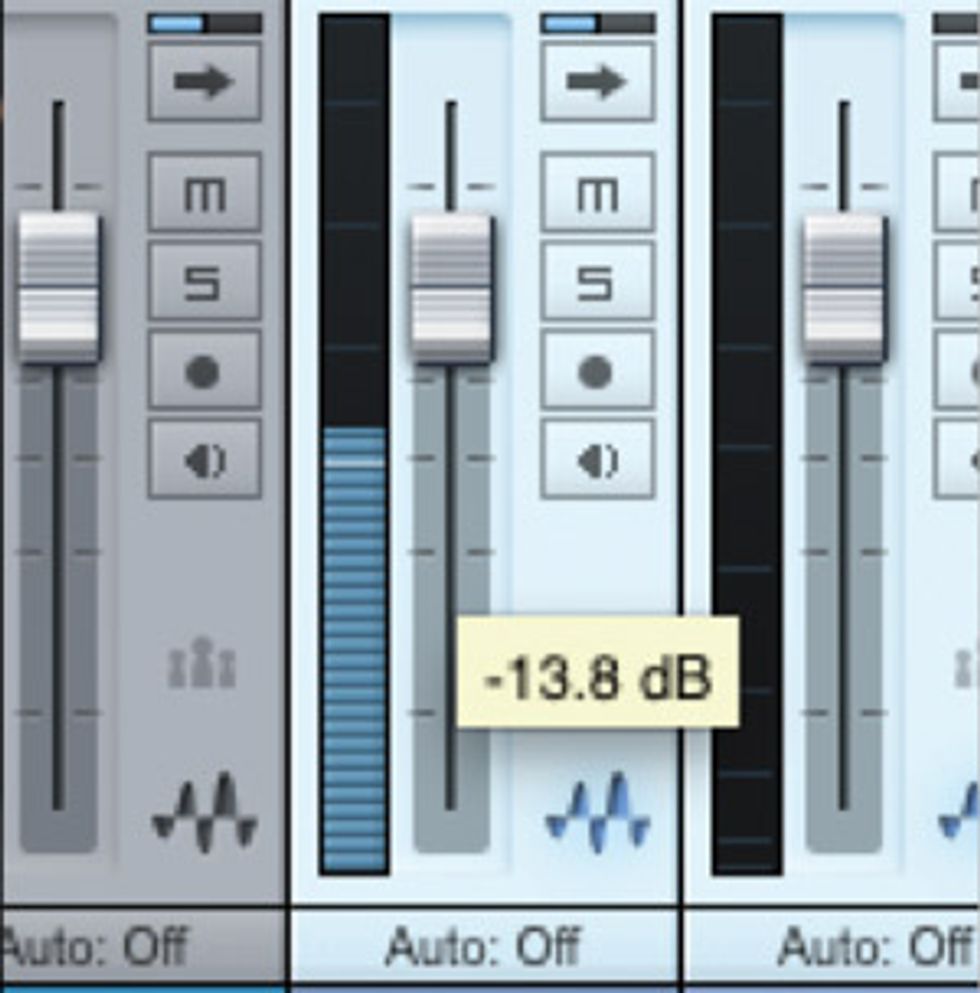

Turn it down. For the best fidelity when tracking, keep levels between −18 and −14 dB on the meters.

1. Turn it down!

In the analog tape days, the goal was generally

to get the hottest signal down to tape

as possible, just short of distortion. When

presented with high levels, analog tape

responds with soft compression and gentle

saturation that sounds great, especially on

drums and other percussive instruments.

But digital doesn’t work that way. It’s not

forgiving of peaks, and if you push it too

hard you run the risk of digital distortion,

which sounds awful. For this reason,

and to allow plenty of headroom for later

processing and mixing, it’s proven best to

record signals to digital at levels in the −18

to −14 dB range on the meters. This allows

plenty of headroom for peaks and for later

work on the tracks. Some audio interfaces

have built-in peak “over” protection, but

do yourself (and your tracks) a favor: keep

the signals in that −18 to −14 dB range,

hard as it may be to resist the temptation

to light up those meters! Your reward will

be cleaner tracks, better dynamics, way

reduced danger of digital distortion during

recording, and easier mixdowns.

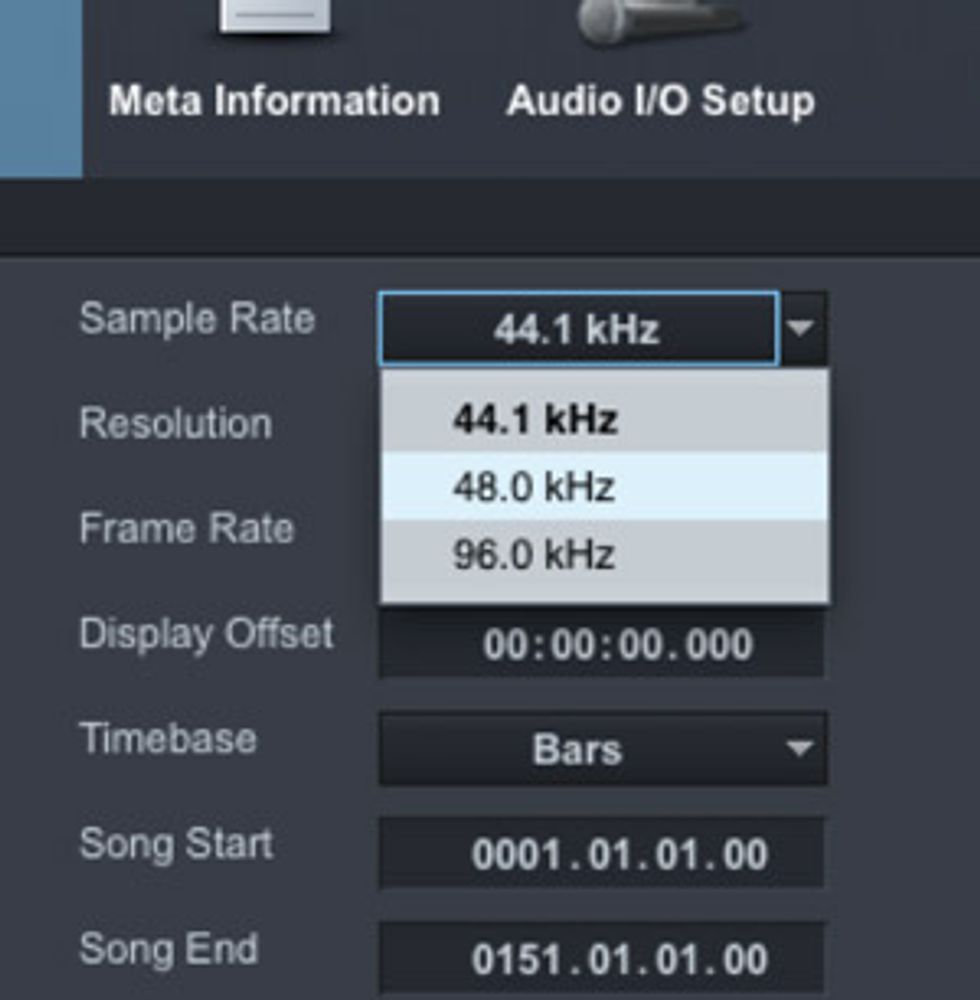

sample rates matter. or not. Unless you have a compelling reason to use a higher sample rate, 44.1 kHz is optimum for most productions.

2. Sample rates matter. 0r not.

The sample rate determines how many “snapshots” of your

audio signal are taken in a second. Sample rate determines

just one thing: the frequency response of the system—in other

words, the highest frequency the system can record. Today’s digital

gear is capable of working at 192 kHz sample rates (or even

higher), which provide frequency response up to 96 kHz—nearly

five times the highest frequency the human ear is generally

credited with being able to perceive. There may be situations

where those super-high frequencies are worth capturing. Some

“golden-ear” listeners claim to hear a difference when those

ultra-sonic frequencies are present, but this assumes the music is

being delivered to the listener on a DVD or some other medium

that supports sample rates over 44.1 kHz. Some recording

engineers also feel that certain types of input filters and plug-ins

work better at higher rates. But for most of us operating in lessthan-

perfect bedroom and basement studios, there are few reasons

to use high sample rates. A big drawback is that you have

to get that high rate converted down to 44.1 kHz to deliver it

on CD, which can potentially impact the audio quality. Another

is that high sample rates dramatically increase the size and computer

load for a project. If you have a full-on Pro Tools HD or

HDX system, that’s no big deal. But if you’re running a native

digital audio workstation (DAW), then that extra load can be a

problem. Personally, I record at 44.1 kHz if the project will end

up on CD or MP3. I rarely work at high sample rates.

(Top)Watch plug-in gain. Even if your mixer channel meters seem okay, it’s possible that you are overloading them from inside one of your plug-ins. (Bottom) Choose where the color comes from. Many plug-ins that model or emulate the sound of vintage hardware units—such as theUniversal Audio Fairchild limiter plug-in shown here—can contribute nice colors to your mixes.

3. Bits matter.

The number of bits in a digital

signal affects its resolution and

dynamic range. Each additional

bit doubles the resolution of

the signal. The difference is

dramatic. A 4-bit signal has 16

steps of resolution to “measure”

and represent the signal—sort of

like using a tape measure only

marked in one-foot increments

to measure something. Moving

to eight bits gets us 256 steps.

Sixteen bits get us 65,536 steps.

And 24 bits jumps us to a whopping

16,777,216 steps! That’s

like using a ruler marked off in

100,000ths of an inch—we’re

talking super-fine measurements.

For this reason, it’s best to track at 24 bit, then convert to 16-bit for CD or to MP3 as the last step in the process. Having all that resolution also allows us to record at conservative levels (see number 1, above) while still having plenty of resolution and dynamic range to make a great recording. If you have a 24-bit system and you record at −18 dB, you’re still getting 21 bits worth of dynamic range (each bit adds 6 dB of dynamic range) and 2,097,152 steps of resolution. That’s plenty for excellent quality.

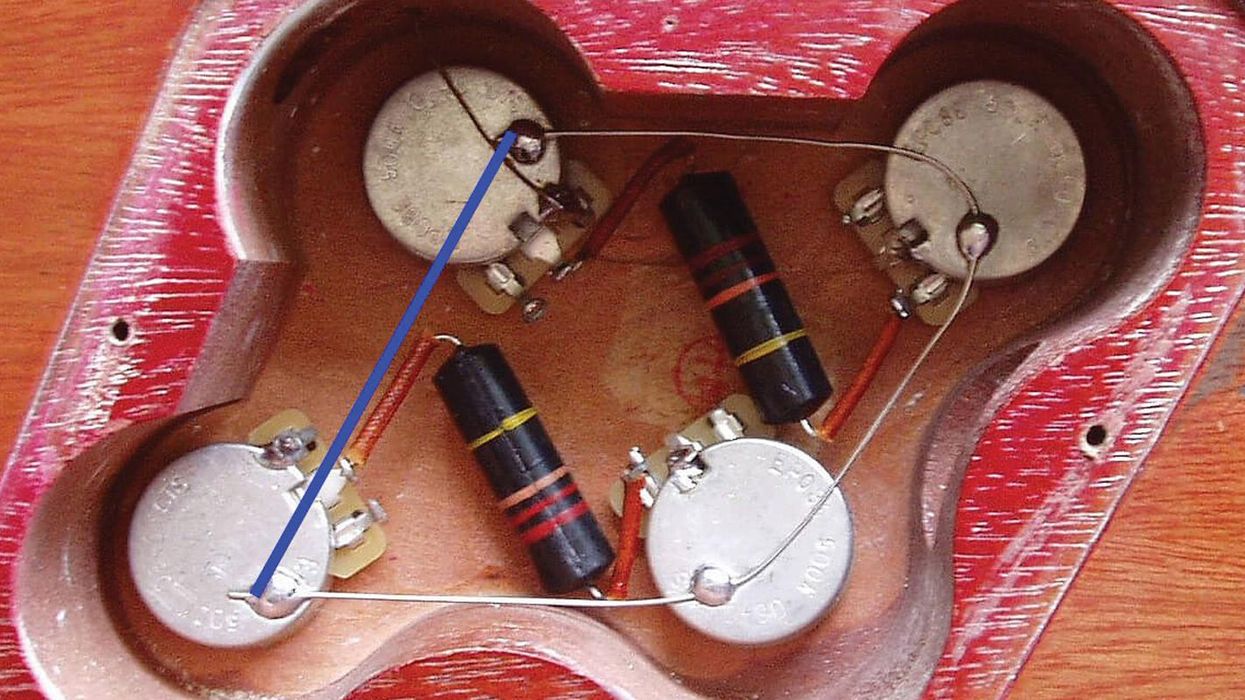

4. Watch plug-in

gain.

It’s so easy to drop plug-ins onto

a track to EQ, compress, or otherwise

process a signal. But be

careful—many of those addictive

little software processors

can change the gain or level of

the signal, which often leads to

clipping (distortion) that’s easy

to miss in the heat of mixdown.

Be sure to double-check the

meters and clip indicators inside

each plug-in to ensure that no

overloads are slipping past you.

Boosting the gain in the plug-ins

too much can also force you to

have to pull down the channel

and master faders later, which

isn’t good gain staging and can

impair the audio quality.

5. Choose where the color comes from.

Analog tape and processors color your recording signal in a slightly different way—that’s part of their

beauty. Today, we can emulate a lot of those colors with modeling software that recreates the sound of the

original gear, including the coloration it provides. By selectively choosing the modeled processing you use,

you can carefully add analog-style coloration exactly where you want it and where it can be most useful.

Drums, for example, often benefit from analog-tape-style or analog-compressor-style coloration. Delicate

acoustic guitar, on the other hand, may not fare so well if you hit it with a highly colored processor.

6. Get it right at the source.

Just because we can do so many things with digital

audio, doesn’t mean we should—it doesn’t relieve

us of the responsibility to capture great sounds at

the source. Life is so much easier, projects come

together so much faster, the process is far less painful,

and the final product is so much better when

the original tracks are in tune, are tonally solid, are

recorded well, and aren’t plagued by background

noise. “Fix it in the mix” is just as much of a negative

with digital as it was with analog.

7. Upgrade the right stuff.

I’ve been covering this in recent installments of my Guitar Tracks column here in

Premier Guitar, but it bears mention in this space, as well. Upgrading or improving

certain things in your signal path will make more difference than others. For

example, I’m a firm believer in having the best monitors you can afford. You hear

everything through those speakers or headphones, so you have to be able to trust

them. I’m also a firm believer in capturing with the best quality possible at the

source. This means great mics and preamps. And a few key pieces of processing

gear, such as a nice analog compressor, can go a long way toward making the later

digital representation of many of your signals that much better.

Monitor Speakers

Under $300

Samson MediaOne 3a pair $99 street

M-Audio AV 40 pair $149 street

Alesis M1 Active MKII pair $239 street$500 to $1,000

Tannoy Reveal 601a pair $499 street

Focal CMS40 pair $790 street

Dynaudio BM 5A MKII $998 streetOver $1,000

JBL LSR4328P $1,559 street

Neumann KH 120 $1,499 street

Sonodyne SM 200Ak $1,590 streetMicrophones

Under $250

Shure SM57 dynamic $99 street

Audio-Technica AT 2035 large-diaphragm condenser $149 street

Rode NT1-A large-diaphragm condenser $229 street$250 to $500

Sennheiser MK 4 large-diaphragm condenser $299 street

Blue Microphones Baby Bottle large-diaphragm condenser $399 street

Shure KSM32 large-diaphragm condenser $499 streetOver $500

Mojave Audio MA-201fet large-diaphragm condenser $695 street

AKG C 414 XLII large-diaphragm condenser $999 street

Neumann TLM 103 large-diaphragm condenser $1,099 streetCompressors

Under $150

Behringer autocom pro-XL

mdX1600 $109 street

alesis 3632 $149 street

dbx 266xs $149 street$299 to $500

art pro-VLa ii $299 street

dbx 160a $429 street

drawmer mXpro-30 $497 streetOver $500

Chameleon Labs 7720 $535 street

aphex model 240 $699 street

tL audio 5021 $999 streetPreamps

Under $150

Art Tube MP Studio V3 $69 Street

PreSonus TubePro $129 Street

Studio Projects VTB1 $149 Street$150 to $500

dbx 286s $199 Street

ART Voice Channel $399 Street

Focusrite ISA One $499 StreetOver $500

Grace Design m101 $565 Street

Chameleon Labs 7602 MKII $719 Street

JoeMeek twinQ $949 Street

the room still matters. The iconic drum track from Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” has been sampled innumerable

times over the years, and a huge part of its classic vibe is due to where it was recorded. In this scene from the

2009 documentary It Might Get Loud, Jimmy Page stands in the foyer of Headley Grange, the East Hampshire, England,

home where Zep recorded tracks for four of their most famous albums. Photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

8. The room

still matters.

This is a corollary to item 7: One of

the best investments you can make

in your digital tracks is to acoustically

treat your recording and control

room. You’d be surprised how

much the sound of the room affects

what you do, and digital captures

all that roominess with perfect clarity

… so make sure the space you

are working in is doing the job.

9. Hygiene is key.

In the analog days, you had to

demagnetize tape heads, clean the

tape path, wind the tape for proper

storage, and perform other routine

maintenance tasks at the beginning

and end of every session. The same

is true with digital—the tasks are

just different. Lots of takes and

edits can result in a ton of files

scattered around your computer

and slowing down your system.

Unused mixer channels and plugins

can end up hiding in the system,

weighing down the project,

and eating up CPU and memory

resources. Lots of small apps running

in the background on your

computer will also sap it of precious

processing resources. Keep it

clean and organized, and your system

will always perform its best.

But basic maintenance extends beyond this to installing current versions of software, having plenty of space available on your recording drive, installing plenty of RAM in your computer, and otherwise optimizing your system for maximum performance. However, don’t do those things the night before a critical session— give yourself plenty of time to learn and test new versions of software or plug-ins before you put them to work for real.

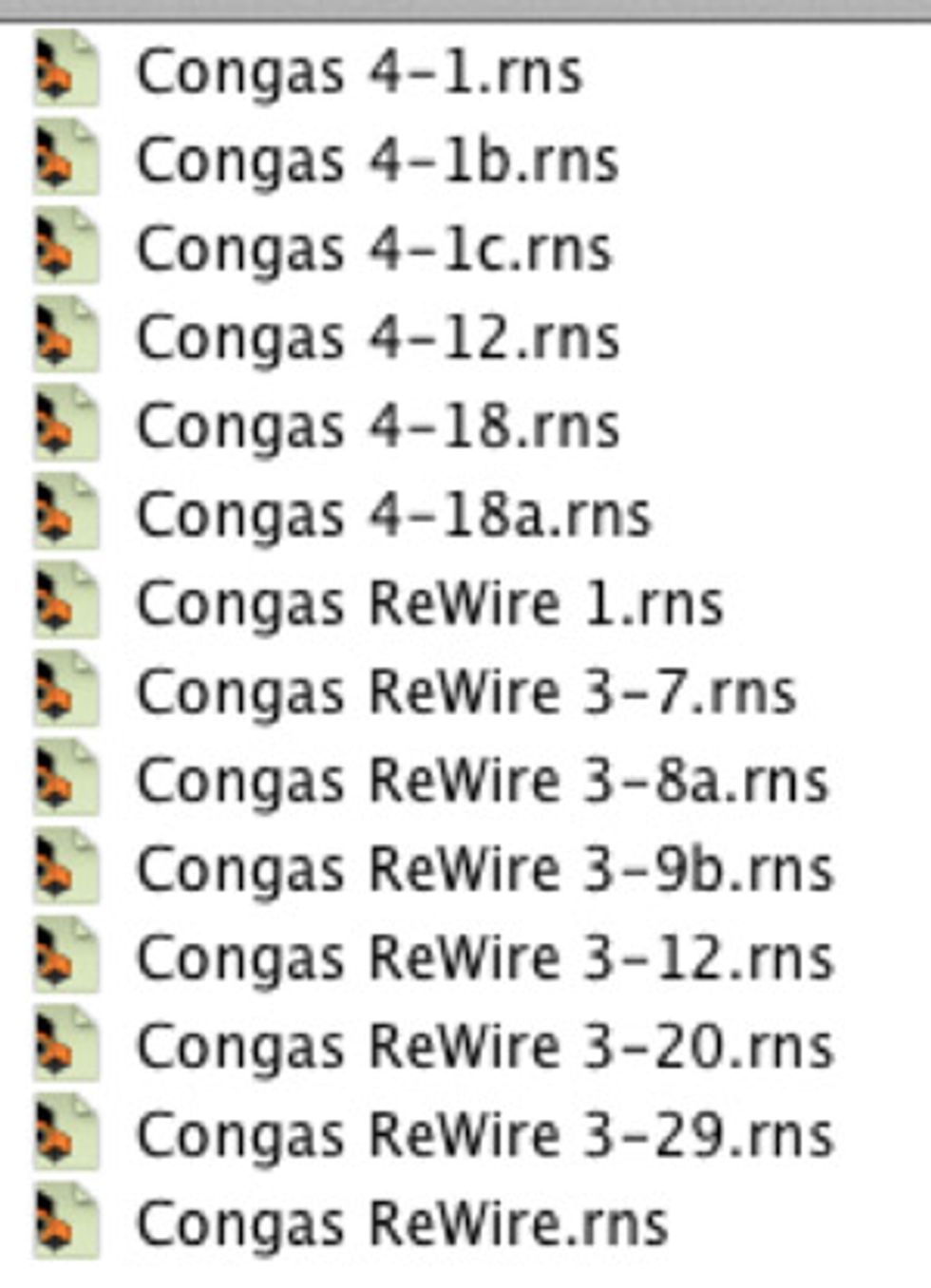

digital data is fragile. Saving multiple versions of a project under new names provides some protection against corrupted fi les—and it’s a great organizational tool—but for real protection, you must back up your work regularly.

10. Digital data

is fragile.

The virtual ones and zeros that

make up digital data are not robust.

One small mishap and your hardwon

tracks can vanish. For this reason,

it’s imperative that you save and

back up your data constantly. By

habit, I hit the save command in my

DAW every time I make a change.

And when I’ve made a significant

number of changes, or I’ve gotten

to the point where it would be

extremely painful to have to recreate

my work, I save a new copy under

a different name. (Project 1, Project

1a, Project 1b, Project 1c, and so

on.) This way, if a project file gets

corrupted, I can always step back to

the last version and work forward

again without losing everything.

Likewise, at the end of every work session, I back up the project to a separate hard drive. That way, if the hard drive in the computer goes down, I’ve still got my work on a second drive and can quickly recover and begin working again.

It’s all about the outcome.

Digital has been a true godsend for musicians who want to capture and distribute pro-quality recordings without waiting for some major label

to finance the dream. It’s made super-powerful recording tools available to pretty much anyone. But it’s about more than just the tools. Keep

these 10 simple tips in mind during all your future recording adventures, and you’ll be pleasantly surprised at how much the quality of your

digital projects improves as a result of such straight-ahead measures. More than that, you’ll find they make studio life easier and less stressful—

which can only portend good things for your creativity and performance quality. Good habits are good habits, whether you’re working with

analog or digital, and in the studio, good habits lead to great recordings!