What would possess someone to fill a station wagon with fragile, heavy, vintage audio gear and drive 3,000 miles for an unrehearsed recording session when you could just as well fly with a laptop, an interface, and a few microphones for a fraction of the effort, time, and space?

The way I see it, if you’re traveling across the U.S. to record in the country’s oldest juke joint with the greatest living practitioner of an esoteric regional tradition, there’s no doing things halfway. I don’t want to preach a kind of analog dogma, but after years of listening to recordings of Jack Owens, Junior Kimbrough, and Fred McDowell on labels like Wolf, Fat Possum, and Arhoolie, I wanted to make every effort to produce my own sessions in the footsteps of David Evans, Bruce Watson, and Alan Lomax, which included using a portable analog setup to capture traditional music in the space where it is authentically made.

So, I brought a Tascam 22-4 reel-to-reel tape machine, several tube preamps, a mixer, and five microphones to produce two albums in two days with 77-year-old Jimmy “Duck” Holmes at the Blue Front Cafe in Bentonia, Mississippi. They are, essentially, modern field recordings done in the old style, produced in the country’s longest-running blues club—hallowed ground where legends like Skip James, Sonny Boy Williamson II, and Howlin’ Wolf all played back in the day. And the feeling of the room, the location itself, is part of not only the sound, but also the atmosphere we caught on tape.

Our approach to recording was simple. Essentially, we followed Jimmy’s ethos of no rehearsals or discussions. (“That’s how the old man does it,” he said.) This was doable because I have been a student of Duck’s for years. When playing with Jimmy, you have to follow each and every note, because he doesn’t adhere to the 12-bar form. It’s truly old school. Fortunately, we also had Grant Smith on calabash, who is a world class musician and an exceptional listener, for our rhythmic anchor.

Ryan Lee Crosby’s Recording Rig

- Tascam 22-4 (tracking)

- Tascam 22-2 (mixdown)

- Teac A-3440 (tape delay)

- Universal Audio LA-610 and SOLO/610 preamps

- Two Akai tube preamps

- Mackie 1604-VLZ Pro mixer

- 3 Shure SM57s

- Sennheiser MD 421

- Shure Beta 91A

- DBX 161 Compressor

- FMR Audio RNC 1773

- Echo Fix spring reverb

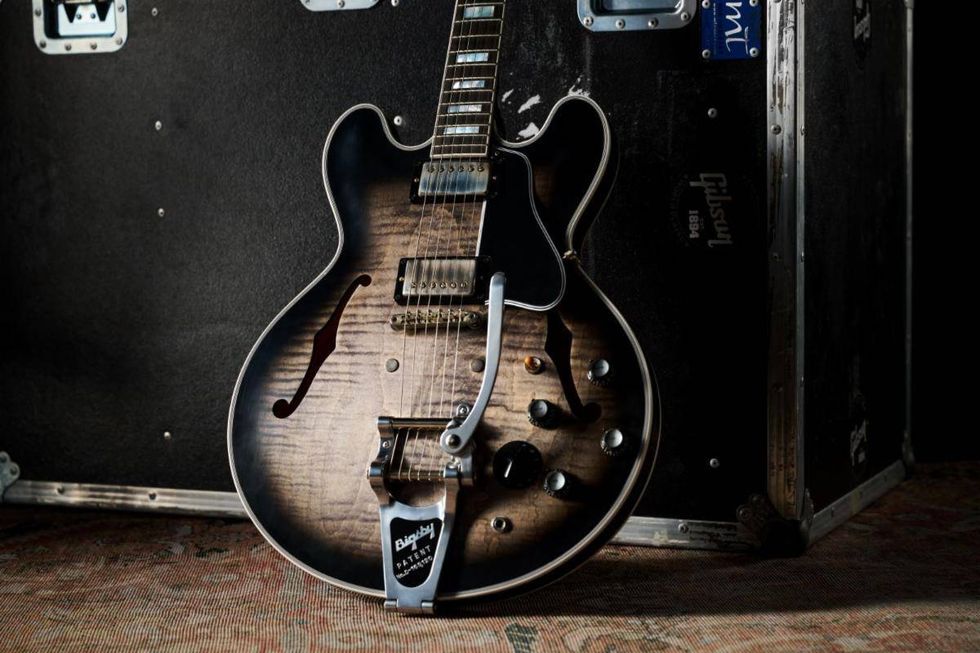

- Fender electric 12-string Jazzmaster (vintage neck/modern body)

- Homemade T-stye thinline

- Evil Twin custom tube amp

- Peavey Delta Blues

And so, over two afternoons, we worked for about four hours to produce both the new Jimmy “Duck” Holmes collection Bentonia Blues/Right Now and my own record, At the Blue Front. The method was to do one take per song, aim to get it right the first time, and keep on going. This approach continued into mixing. I recorded and mixed the Holmes album entirely analog, without overdubs. On my album we added shakere (a West African percussion instrument), some harmonica, and a few vocal edits. I chose to do this with a DAW, for the flexibility as well as the fidelity, because although I prefer to stay all-analog whenever possible, I won’t forgo the use of a computer on principle. It’s important to do what’s best for the music and the recording, ultimately.

“I find, as a listener, player and producer, that analog can draw us into the present, into the heart of direct, physical, musical experience.”

I believe there is a lot to learn from working this way. When the tone of the album comes from live performance, then what’s compelling about the work is the spirit, chemistry, and ability of the people behind it. The tracks on these albums aren’t perfect and I wouldn’t want them to be. They are, however, unquestionably human. If I want perfection, I’ll ask AI to do it for me.

This is not my first analog project. Almost every recording I’ve made over the last 20 years has involved a tape machine, to varying degrees. I find there is something so inspiring about having the limited parameters that come with analog, and I relish working in real time, away from the distractions of a computer screen. I find, as a listener, player, and producer, that analog can draw us into the present, into the heart of direct, physical, musical experience. In short, it is all about the playing and the sound.

The editing capabilities of the computer cannot be matched, and they have their place. But I believe that nothing compares to the sound and feeling of people making music in a room together. And nothing captures this quite like tape. It doesn’t have to be perfect, it just has to be real. And, besides, isn’t perfection boring?