Before Cream recorded “I’m So Glad” in 1966, few music fans knew about the sound that emanated from the area around the rural Delta town of Bentonia, Mississippi—an elegantly cadenced, droning, minor-key blues style, mostly sung in keening falsetto, and full of songs about the Devil and hard life gone harder. But those who attended the 1964 Newport Folk Festival saw the re-emergence of its main torchbearer, Skip James, after a roughly 30-year hiatus from recording and performing. James’ Newport appearance was the perfect comeback for this mysterious-sounding variant on Delta blues. As he took the stage, it was shrouded in fog, and just as he struck the first notes of his song “Devil Got My Woman,” his voice keening in falsetto over his open-D-minor-tuned 6-string, the fog parted, and both James and the music of Bentonia were revealed once again.

Okay, maybe that’s a little florid, but the Bentonia style does have a dark romance wrapped into its sound and lore. And despite the efforts of Clapton, Bruce, and Baker, it has remained rarified—hardly heard outside of its homeland or the rooms of blues obsessives. Since 1931, when James recorded his sides for Paramount Records, there have been only four other notable practitioners: James’ mentor Henry Stuckey, who never recorded; Jack Owens and Bud Spires, who cut one album as a duo; and Jimmy “Duck” Holmes.

Holmes, at age 69, is the last man standing. He’s not as fleet or skilled a player as James, but his voice sounds every bit as old and sunbaked as the cotton fields where his parents sharecropped before opening the Blue Front Café in 1948. And he uses the same open E-minor and open D-minor tunings that have always characterized the Bentonia sound.

Today, Holmes still runs the Blue Front, and that’s where his fifth and newest album, the recently released It Is What It Is, was recorded. “Other than the town not having as many people, the Blue Front is still just like it was on day one,” Holmes says. “I used to have a pool table and even a couple video games, but I got rid of the pool table in the late ’90s. When it got to the point where the pool table crowd was crowding out the regular people just socializing, I took it out.

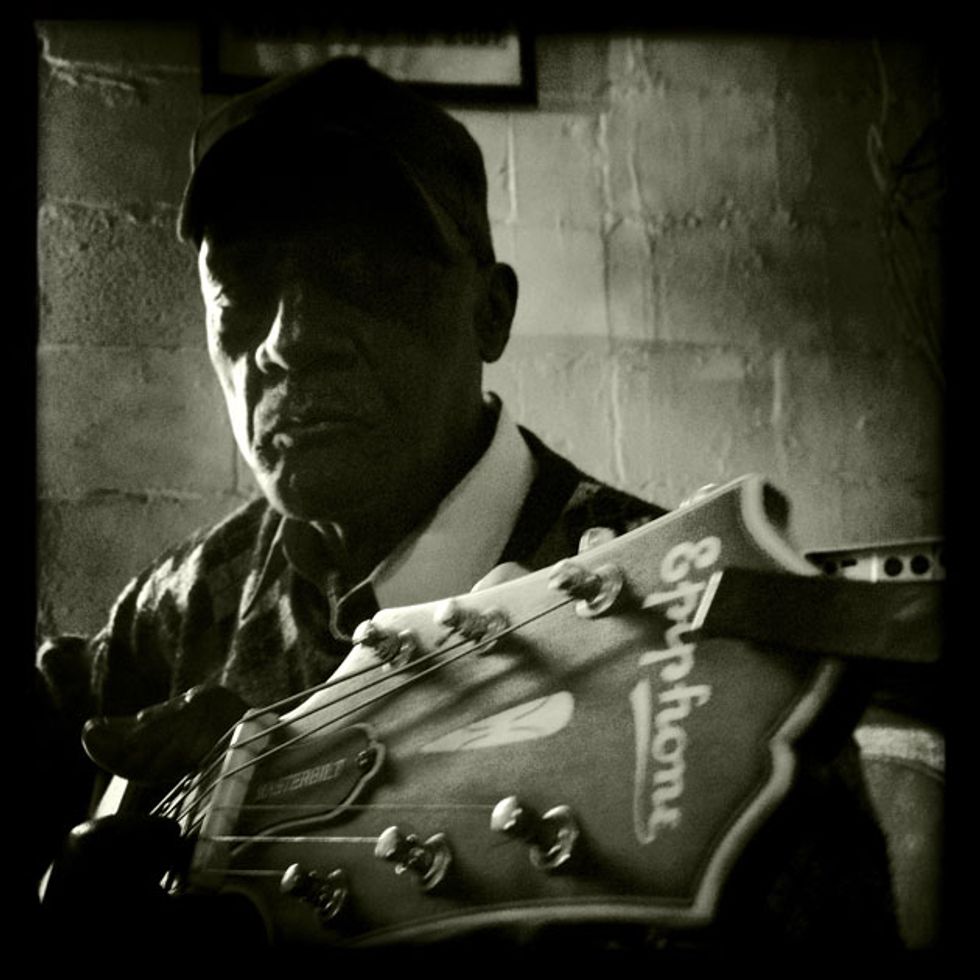

The life of Jimmy “Duck” Holmes and the history of the Blue Front Café are intertwined. Here, Holmes talks about both and provides the soundtrack for his narrative with his bawling, soulful voice and Epiphone Masterbilt EF 500RA guitar.

“I never had a problem with fights and people carrying on,” he continues. “I put the first pay phone [in town] in there. It was right by the bar. When I took it over in 1970, I had a strict policy and everyone knew that I didn’t mess around. If people get rowdy or start a fight, everyone knows I’ll drop a dime on them. It took about six months for everyone to realize and after that it’s been smooth sailing.”

That’s 46 years of serene navigation, but it wasn’t until 2006, when Holmes cut his debut album Back to Bentonia, that his career as a musician caught a broader wind and he became a regular at festivals in the U.S. and Europe. It Is What It Is is state of the Duck—nine tracks that draw on his life and times in rural Mississippi, as well as the haunting sound of the blues that has long echoed across the flatlands of his hometown. They include “It Had to Be the Devil,” long a staple of the Bentonia blues songbook, and the practical philosophy of the title track, as well as the reflective “It Is What It Was.” Holmes pairs droning chords plucked out on his Epiphone Masterbilt acoustic, or an electric guitar that sounds plugged into a ’50s car radio, with his lonesome, bawling-calf voice—a marvelous, elemental bray. For him, like any true juke joint rambler, tuning, tone, and precision aren’t as important as to-the-bone-honesty and vibe. And It Is What It Is is packed with both. Especially vibe. Listening to the album is as close as you can get to an authentic, old-school juke joint today without exploring the nearly forgotten corners of the deep South.

And even those corners have changed. Reminiscing about his native town, Holmes says, “It used to be that most of the black people in the community worked as farm laborers or did something on the farm. Now, hardly anyone works on the land farming. Machines do all the work now. There’s not 10 black people working in the field. And there were a lot more people who played music, including the blues. People didn’t look at it back then like they look at it now. For an individual to play a guitar back then was something common. But to know someone who plays blues music now, it raises eyebrows. Back then you had several blues guitar players, harmonica players, stuff like that, here. They all weren’t on the same level, but they were in the community playing.”

Holmes seriously committed to guitar in the late ’70s, when Jack Owens took him under wing. Like Skip James, Owens had learned to play the Bentonia blues style from Henry Stuckey. “I’d always had an ambition to learn to play the guitar,” says Holmes. “Not necessarily blues guitar. I was sort of drafted into it. Jack really wanted me to learn how to play the Bentonia style of blues he learned from Stuckey.”

One reason the Bentonia style is relatively obscure is that its main practitioners never cared to travel, as Robert Johnson, Charley Patton, and other Delta blues proponents did. The Bentonians had farm jobs and families that kept them tied to their homes. And James, who auditioned for Paramount in Jackson, Mississippi, and recorded his historic sides for the label in Grafton, Wisconsin, gave up the music business after his 78s tanked during the onset of the Great Depression. Until his comeback, he split his time between farming, serving as choir director of a local church, and the ministry.

As for the unrecorded Stuckey, who seems to be the linchpin of the Bentonia style, Holmes explains that he “was a devoted family man. He had a big family and wasn’t going to leave to go play the guitar on the weekends until he was sure his family had what they needed, their groceries were made, and they were okay. Then he’d go play guitar and make some money and be back and ready to work on Monday. He was a farmer. He sharecropped with my dad. He wasn’t real tall, but he was a big man, like a boxer. Big boned. Big muscles in his arms and shoulders. He kind of strutted when he walked. By looking at him, you’d think he would have had a deep voice, but when you heard him talk you’d think it was a different person. That’s why he could sing up there like Skip and Jack did.”

Skip James’ take on Bentonia blues is definitive. Here, he performs in the “blues house” at the 1966 Newport Folk Festival for an audience that includes Howlin’ Wolf (at right) and Mississippi John Hurt (behind James). He’s playing one of his signature songs, “Devil Got My Woman.” His highly original, keening vocal approach and his intricate picking are on display.

Holmes began to tinker with the guitar in the early ’60s, on Stuckey’s old instrument—“just hitting the strings, just making a sound. Then for Christmas my daddy bought me a little yellow-and-black plastic guitar. That was my first guitar that I owned for myself. I broke the first set of strings on it and never did get any new strings, so it kind of got pushed to the side.

“Then in 1963, I visited my uncle in New York and he had a guitar. It was electric and that kind of rekindled the fire a little bit. I messed around with the guitar again when I visited the next couple summers. But then after that, I really didn’t mess with it until around 1972.”

At that point, Holmes was more under the sway of Tommy West, a bluesman from the Mississippi hill country above Batesville and Oxford. The hill country is home to yet another distinctive regional style, based on one-chord drones, band arrangements that pass combined rhythm-and-melody lines from instrument to instrument, and intense rhythmic drive—even in its guitar solos.The most famous, modern-day proponents of Mississippi's hill country sound are the late R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough, who followed in the footsteps of Fred McDowell.

“Then, around ’76 or ’77, Jack started coming by the Blue Front a little more,” Holmes continues. “I think it must have been around ’74 or ’75 that I actually bought my first guitar. I don’t know what kind of guitar it was, but I bought it at RadioShack. As a matter of fact, that’s my guitar on display at [Clarksdale, Mississippi’s] Delta Blues Museum. So from then on, I’d play with the local blues musicians and these old guys would come to the Blue Front. Jack, Tommy, Bud, Cornelius Bright, Dodd Stuckey, and others would come by. As soon as they heard that Carey Holmes’ son, Duck, at the Blue Front, had a guitar—they started hanging here. They’d take turns playing my guitar. Dodd Stuckey, Henry’s brother, showed me how to make music rubbing the broom handle on the floor. Adam Slater was the first one to show me about the open tuning. I wasn’t particularly interested in playing the guitar, but he would come by most every day and he would ask me if I’d learned anything. I would tell him ‘yeah,’ but I probably hadn’t even picked it up. Cornelius would come in and say, ‘Where your box at? Let me fool with it a minute.’ He’d pick it up and I’d go sit outside. If I had shown him the interest I later had with Jack when he started teaching me, I would’ve picked it up a lot earlier. Cornelius could play. And he had a great voice. Great voice.

“Then in the ’80s, when Jack really started to teach me, he really wanted me to learn it. He couldn’t read or write and he didn’t know what any of the notes were, but he would play and just tell me, ‘Watch my hands, boy. Watch my hands.’”

In an excerpt from Robert Mugge’s 1991 documentary Deep Blues, narrator Robert Palmer talks about Bentonia’s devil-song tradition before introducing the team of Jack Owens and Bud Spires. Owens is playing his 12-string Kay with only six strings, and his singing reflects the high-and-lonesome influence of both Henry Stuckey and Skip James.

Owens remained the region’s preeminent stylist, driving himself to gigs, sipping whiskey, and telling stories nearly right until his death at age 94 in 1997. And then Holmes began to get more of those gigs, at places like the Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Festival in Clarksdale, and eventually, around the world.

Asked about his preferred guitars, Holmes says, “I’ve never been too choicy about that. I know some are probably better than others, but my main concern is if I can get it tuned right and get the right sound coming from it. It don’t normally make me no difference. But right now I play this Epiphone Masterbilt EF 500RA. I’ve played it most every day here at the Blue Front or at festivals since maybe 2006. It has the best sound of any guitar I’ve ever picked up. To me, it sounds exactly like the hollow box that Henry Stuckey played. That’s the guitar I played most of the new album on.

“Part of the sound,” Holmes asserts, “comes from the strings. When Jack was teaching me to play, he swore by Black Diamond strings. He wouldn’t play anything else. That’s the sound I got used to, so that’s probably why I prefer them today. But to really play the Bentonia style, you need a slick G. It’s unwound so your finger isn’t swiping the grooves when you slide. Stuckey’s guitar was a big-bodied mahogany guitar with a deep, full sound. This Masterbilt isn’t near as big, but it sounds just as full. I’ve had people try to give me a guitar, but, nah, I’ll stick with this Masterbilt.”

The decidedly janglier sounding “Love Alone” on It Is What It Is was played on a 1972 Eko Ranger 12-string. “That’s the exact same year and model that Jack played,” Holmes reports, “but he only had six strings on it. He liked that wide neck and the extra space for his fingers so he wouldn’t smother two strings out with those big fingers. I’ve never liked electric guitars much. I don’t care for those solidbodies with all the extra features, like a whammy bar, reverb, and all that. But I do like that ’58 Harmony Stratotone Jupiter that I played on “It Had to Be the Devil” and “Buddy Brown” for the new album. It’s got its own sound. It’s not fancy, but I like it.”

Holmes has his own opinion on Bentonia’s open tunings. “Now, some like to say that Bentonia tuning is an open E-minor or open D-minor. I’ll tune the guitar to a straight open D-minor if other people are playing so the harp can get lined up,” he says. “But if it’s just me, I’ll tune it down from there, too. I don’t know how it’s actually tuned, you know—if it’s a B or D or something. I just tune it by ear to what I was taught. I let other people argue about what to call the tuning. To learn this music, the first thing is you gotta want to do it. Don’t worry about making a mistake; roll on. Play every day, learn the fundamentals, and then play from your heart.”

With no other players currently recording or performing in public in the Bentonia style, is Holmes the last of his musical lineage? “I think a lot about that,” he says. “Like Jack did for me, making sure I learned how to play, I would like to do that for a few people. My nephew, Larry Allen, lived next door to Jack forever. As a little kid he’d go over and listen to Jack’s stories and listen to Jack play. Jack showed Larry how to play, but Larry hasn’t played the guitar for a long time because he works a lot. He’s definitely getting it, but he hasn’t had the time. He’s going to be good.

“I also feel like my grandson, E.J., is coming along. I could send for him right now and he’d be able to play what I’ve taught him. I don’t want to push it on him. I don’t want to make it a chore or make it boring. He’s going to get it. It just takes practice.”

And Holmes intends to carry the torch for as long as possible. “I thank God for being blessed enough to be able to have the opportunity to play a kind of blues people enjoy,” he says. “I really just want to create music that stays true to those old guys who taught me and that people appreciate. I’ve never cared for being famous or wealthy. I just want to leave behind a positive example and impression. That’s it.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)