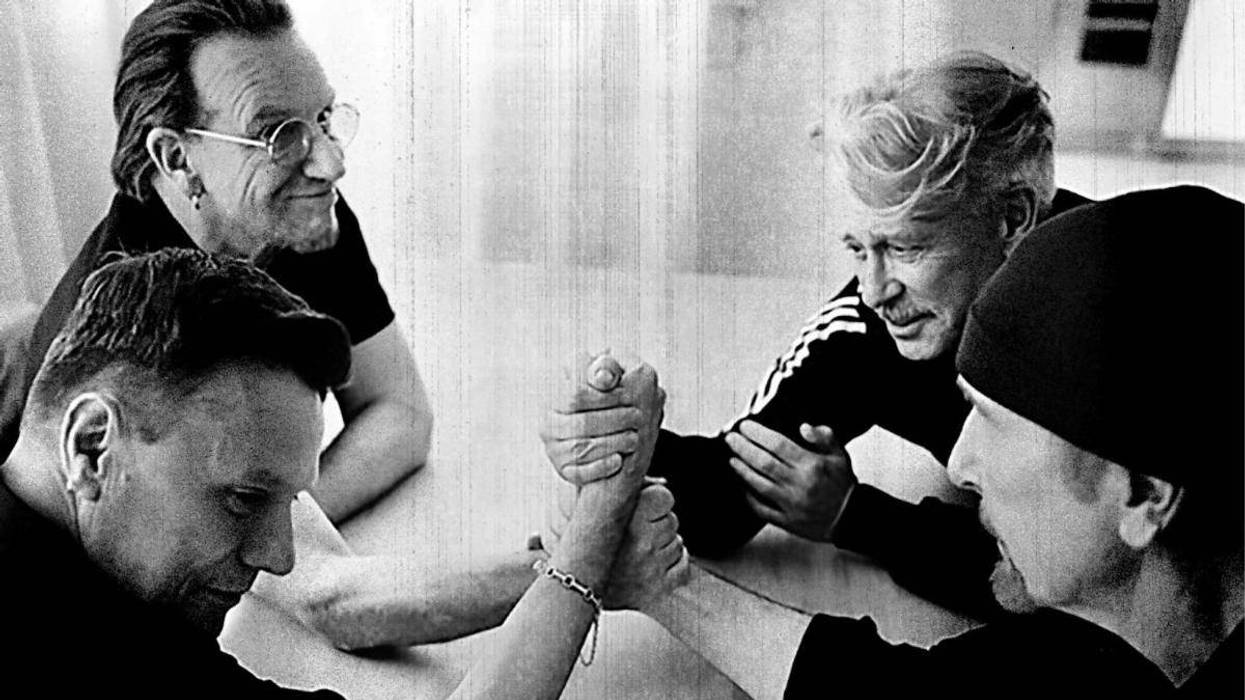

This metal-bodied Rickenbacker (c. 1935) and wood-bodied Vega (late ’30s) improved playability and provided the ability to transmit sound electrically, but still struggled to compete with the big-band sounds of the day due to inadequate amplification systems. Photos courtesy Lynn Wheelwright, Origins Collection

Watching We Jam Econo, a great documentary on punk pioneers the Minutemen, it got me thinking about bass. Mike Watt, the band’s bassist, played some seriously mean riffs on his 4-string, but according to the movie, the first time he saw a Fender Precision in the store, the thickness of the strings, the length of the neck, and the imposing mass of the whole instrument scared the snot out of him.

We don’t talk about bass much around here—it is, after all, called Premier Guitar for a reason. But it’s a solid fact that a lot of our gigs would be a lot less groovy without the thumping low end of the guitar’s 4-string brethren. As anyone who reads this column knows, I like to get the story straight, especially when it comes to history. Knowing that a lot of guitarists—and even bassists—out there think that electric bass goes back about as far as Leo Fender’s workbench in 1951, I thought we’d take a couple of columns to see just what life was like before Leo made it “easy” to pump out the low end.

Throughout the years between the turn of the 20th century and World War II, American music evolved from basically European-rooted dance music to being very simplified, downbeat-centric, and influenced by colloquial and provincial styles. That’s a massive oversimplification, but we’re getting somewhere with it. The two main American musical forms, jazz and blues, both cropped up during this period as well, and each relied heavily on syncopated rhythms driven by percussion, low-register brass, or stringed instruments. By the late 1920s, a jazz band could have either a tuba or a bass viol pumping out rhythm, sometimes both. The tuba began to drop in popularity to the bass viol in the early 1930s. The growing country music genre in particular eschewed the brass-band feel of the tuba for the down-home thump of the bass viol. Musicians in the jazz world also began to migrate to the viol for its playability in comparison to the brass behemoth.

Almost as soon as this migration took place, the limitations of the bass viol in a modern band setting became apparent. The foremost issue was volume, but the second issue was playability. Even if it was easier to thump walking lines on a viol, the size of the neck and strings made it a specialty instrument that only a small portion of the playing population could handle. Then, as now, most guitar players wouldn’t touch the thing. Beyond that, string basses don’t crank out the volume. Even in comparison to an unamplified archtop guitar, the viol is but a whisper. Put it next to a drum kit or a banjo and it’s lost. Builders and inventors immediately set out to find a way to make the string bass louder and more accessible to a wider range of players.

In the 1930s, electric amplification was a new thing. Seeing the success of electrically amplified guitars, violins, and banjos, builders looked at ways to do the same thing for bass. To address playability, a number of builders attempted to make bass instruments that utilized a standard, fretted neck and fretboard. Gibson, among others, experimented with oversized tenor guitars and mandolins. These instruments were somewhat easier to play, but lacked volume, and their tone didn’t impress either.

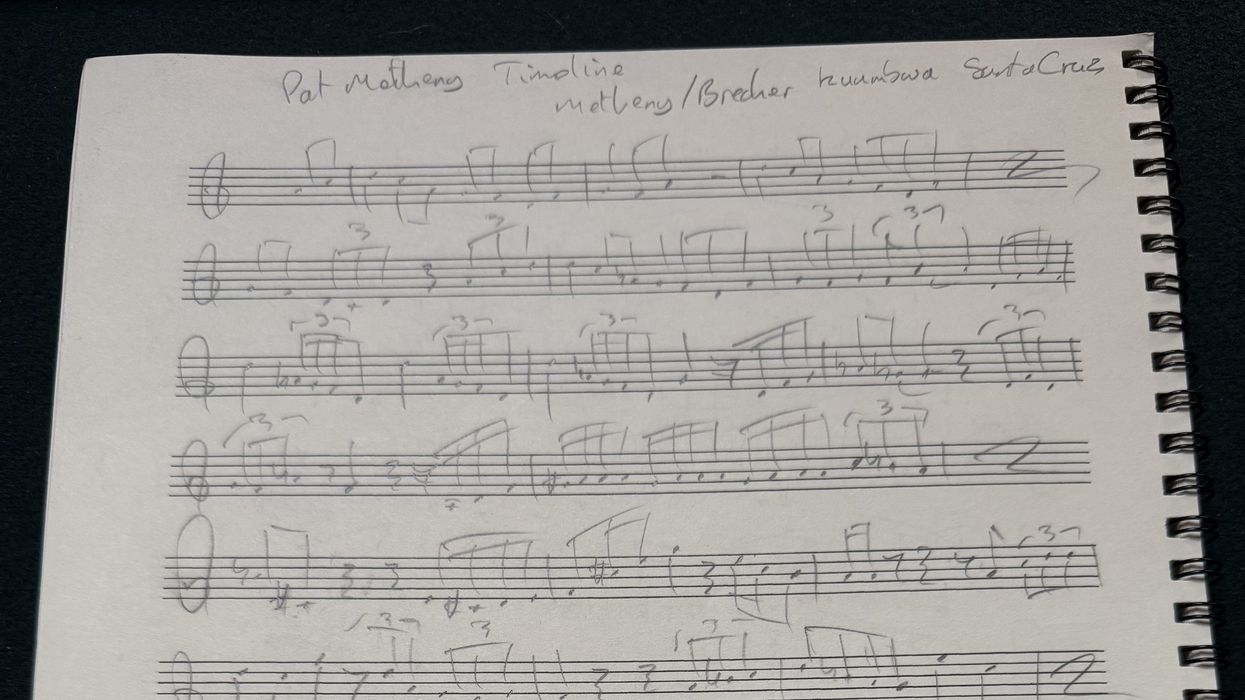

On the flip side, other builders stayed with the traditional bass viol neck and fingerboard, but looked at ways of improving volume. Displayed here are two very early examples of the electric upright bass, courtesy of Lynn Wheelwright, who is the owner and curator of the Origins Collection of early electric instruments. Both feature a streamlined body, traditional-size bass viol neck, and early electro-magnetic pickups. The metal bass is a Rickenbacker circa 1935. The wood bass is from Vega and was available in the very late 1930s.

“The Rick uses gut strings with a ferrousmetal wire wrapped around the string where it passes through the horseshoe magnets,” explains Wheelwright, an expert on early pickup technology. “The Vega can use any strings as it takes the vibration from the plate the bridge sets on. The plate floats on rubber grommets at each corner. Attached to the underside of the bridge plate in the center is a slim rectangular ferrous-metal rod. This rod passes through a round coil that is surrounded by horseshoeshaped, ferrous-metal pole pieces. The metal rod acts like a string as it vibrates within the coil energized by the pole pieces; a larger horseshoe magnet magnetically charges the pole pieces. The entire assembly housed under the bridge plate is adjustable so the best signal can be obtained. There were a number of variations on this theme, beginning with the Stromberg Electro—the first electrified guitar back in 1927.”

“These basses played similar to a standard upright bass, with the advantage of the streamlined body,” says Wheelwright. “Although still modeled after the viol, they were at least a known evil. The major limitation was in the amplifiers themselves.”

Clear bass tone, even today, requires enough wattage to provide clean headroom in volume before ranging into overdriven territories. In the 1930s, few musical amplifiers ventured above 15 watts. Larger amplifiers were available, but they were generally reserved for theaters and public address systems, and large enough to fill a good-sized closet.

Throughout the 1930s, playability and volume remained the challenges in finding a true electric bass solution. Next month, we’ll see glimmers of the future as guitar, bass, and amp begin to come together.

Wallace Marx Jr.

Wallace Marx Jr. is the author of Gibson Amplifiers, 1933– 2008: 75 Years of the Gold Tone. He is a lifelong musician and has worked in all corners of the music industry. He is currently working on a history of the Valco Company. He is a children’s tour guide at the Museum of Making Music, a struggling surfer, and he once hung out with Joe Strummer.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig