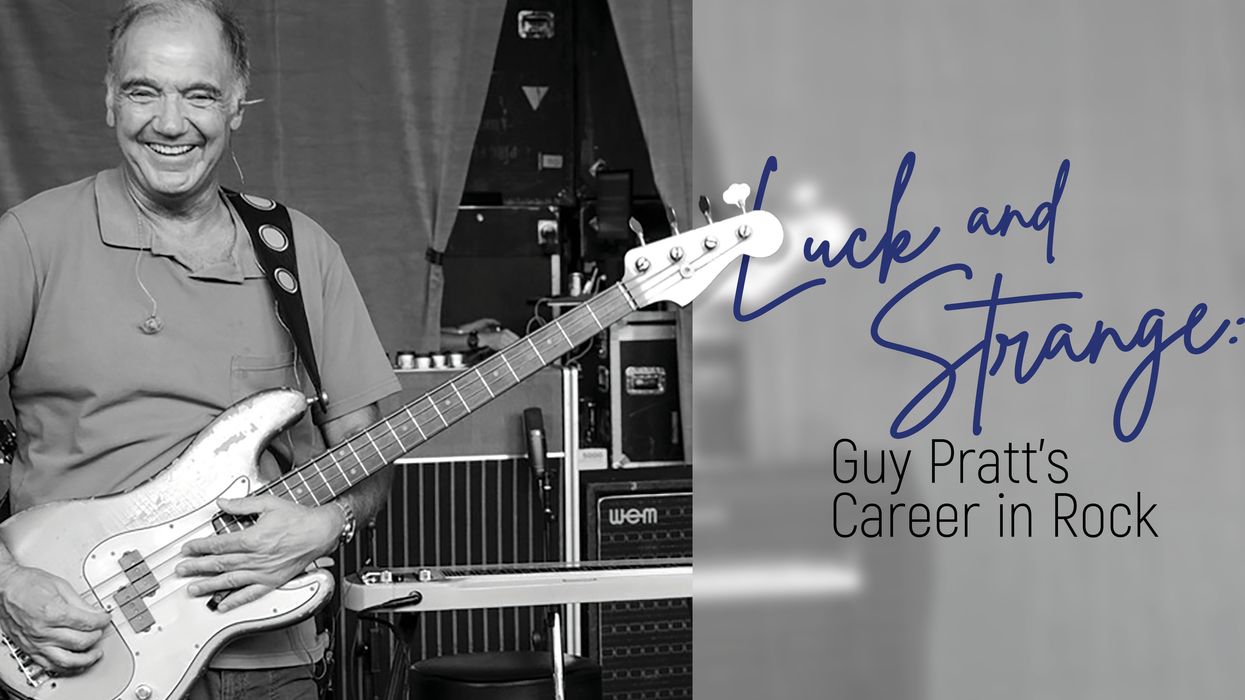

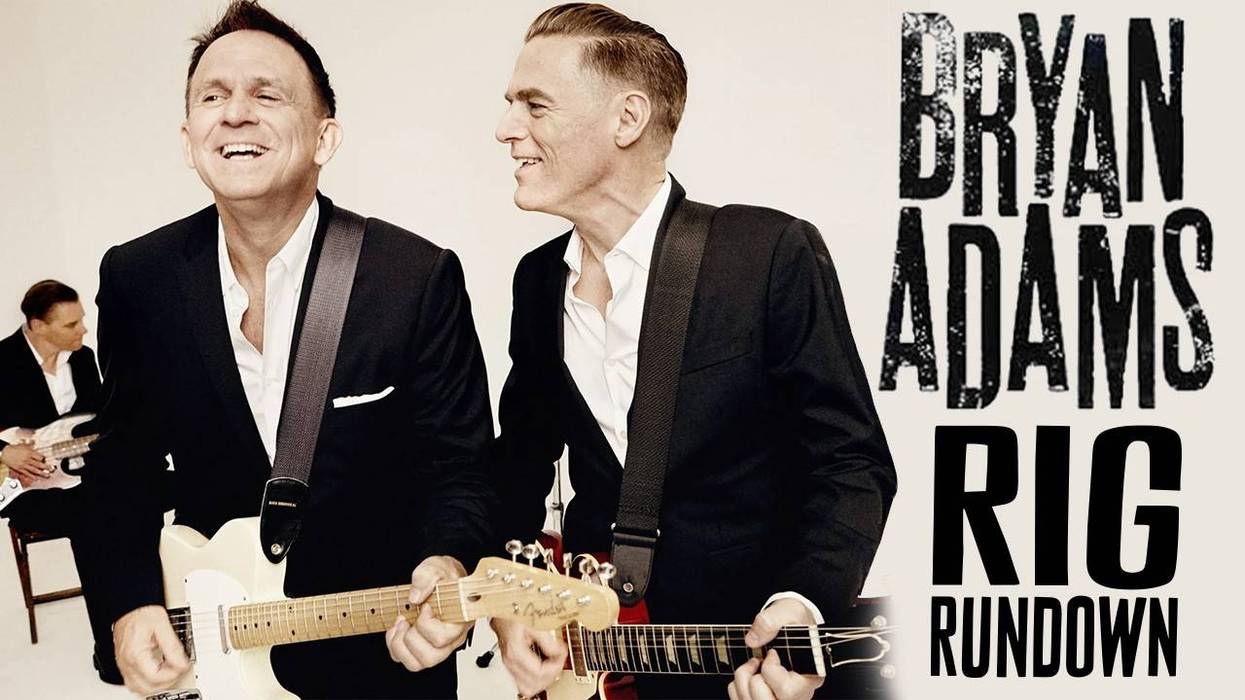

Over four decades, the Grammy-winning English bassist has held down the bottom for Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry, Pink Floyd, and David Gilmour. He’s recorded with everyone from Pete Townshend to Madonna and Michael Jackson, and he’s also a popular podcaster and stand-up comic. Whatever’s next, he’s ready.

If Guy Pratt’s name doesn’t resonate with you, his bass playing certainly has. He’s held the low end down for Pink Floyd and David Gilmour since 1987’s Momentary Lapse of Reason tour, and elsewhere in the Floydian universe he’s a member of Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets, which specializes in the legendary band’s early music.

But wait, as the old huckster’s line goes, there’s more. Lots more. He’s also a longtime member of Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry’s band, and has toured with the Smiths. As part of the new wave band Icehouse in the early ’80s, he scored on the European and Australian charts and opened for David Bowie, and then springboarded into a series of higher profile gigs. In the studio, those have included sessions for recordings by Gary Moore, Michael Jackson (“Earth Song”), Tears for Fears, Echo & the Bunnymen, Iggy Pop, Tom Jones, Whitesnake, the Orb, Debbie Harry, Robbie Robertson, Madonna (“Like a Prayer”), and, in 2022, Pete Townshend. He also shared a Grammy for his playing on “Marooned” from Pink Floyd’s The Division Bell.

And yes, there’s still more. In addition to Pratt’s many TV, film, and theater scores, the amiable London native embarked on a sideline of stand-up comedy beginning in 2005, when he took his one-man-plus-bass show to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. That show, My Bass and Other Animals, spawned his book, and he’s toured two more original comedy productions since. In his spare time, he started a podcast, Rockontours, with Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp, a co-conspirator in the Saucerfull of Secrets band. Their famous guests, spinning tales of the musical life, have included Nick Mason, Bob Geldorf, Phil Manzanera, Trevor Horn, Chris Difford, and Adam Duritz over 213 episodes.

Last year, fortunate concertgoers got a chance to hear Pratt on Gilmour’s 21-concert, four-city tour behind Luck and Strange, an album where Pratt’s playing is woven into the deep currents that support the gorgeous tide of music created by the guitar giant and his hand-picked ensemble in the studio.

There’s an old saying among musicians that if you always want a gig, play bass or drums. Just before his teens, Pratt settled for bass. “I wanted an electric guitar,” he recalls. “I fell in love with electric guitar. Simple as that. I begged my parents, and of course mum said, ‘Oh darling, why don’t you get a nice Spanish guitar?’ ‘Spanish?! I’ll do that at school.’ Rock ’n’ roll was outside the school gates back then; it wasn't where we are now. And it had to be electric. The joke I would say is that actually a toaster would have been closer to what I was after than a Spanish guitar. So I asked for a bass. My mum and dad clubbed together and got me—because my birthday’s near Christmas—a bass guitar for Christmas and birthday. It was really weird … huge and kind of confusing, and I didn’t have an amp. But when I went back to school two weeks later, there were three kids who had got electric guitars for Christmas. Of course, if they wanted to be a band, they needed me, so I had my pick.” And so Pratt’s career began.

Pratt with his favorite bass, “Betsy,” a 1960 Fender Jazz model, in his home studio.

Guy Pratt’s Gear

Basses

- 1964 Fender Jazz Bass (named “Betsy”)

- 1960 Fender Jazz Bass (stack knob; present from David Gilmour)

- Nash Guitars T-style (w/ P- and J-bass pickups)

- Nash Guitars P-style

- Spector NS-2

- Lakland fretless bass

- Stratus 5-string

- Rickenbacker 4001V63 (w/ Nick Mason‘s Saucerful of Secrets)

- Rickenbacker 4003 (w/ Nick Mason‘s Saucerful of Secrets)

Amps

- Ashdown Guy Pratt Signature Interstellar-600

- Ashdown CL-10 cabs

Effects

- TC Electronic Hall of Fame

- Boss ODB-3 Bass Overdrive

- TC Electronic Subnup

- Ashdown Bass Graphic EQ

- Two Boss GEB-7 Bass Equalizers

- Boss DC-2w Dimension C

- Peterson Strobostomp HD

- Demeter Opto Compulator

- Custom Pedal Boards router

- Lehle volume pedal

- Ashdown footswitch

- Dunlop JCT95 Justin Chancellor Cry Baby Wah

- Dunlop volume pedal

- Boss Digital Delay DD-500

- Foxgear Echosex Baby

- Boss OC-Octave

- MXR Phase 90

- Origin Effects Cali76 bass compressor

- The Gig Rig QuarterMaster QMX-10

Strings & Picks

- Elites Stadium Series Roundwounds (.040–.100)

- Dunlop Tortex Triangle .88 mm (for older Pink Floyd songs)

I’ve been listening to your playing since the ’80s, when you started working with Bryan Ferry and with David Gilmour and Pink Floyd. Your tone has evolved over the decades, from what I would describe as a pointier sound.

Yeah, it was all front end. I was playing a Steinberger and it was bridge pickup. There was a lot of slapping. In the ’80s, bass was almost doing a different job because with a lot stuff I did there was a keyboard bass as well. Like when I used to work with [producer, drummer, and an original member of Duran Duran and the Lilac Time] Stephen Duffy, often I would go into the studio and I went on after the vocal. And my job was to kind of put stuff in the gaps, more like a horn part than bass.

It was the first drum-machine generation, and suddenly LinnDrums were everywhere. The bass wasn’t necessarily doing the job it had to do. You weren’t in the room with the drummer laying the thing down. With the birth of hip-hop and the new romantics and then bands like Simple Minds, everyone was coming from a quite funky perspective. There was a lot of stuff happening with technology and the bass responded really well to technology, with the Steinberger and various effects and amps. It felt like guitar was really taking a back seat at that time, too.

I mean, I was an asshole. Twenty-one-year-olds are assholes, aren’t they? So I guess the way I would look at it is I’m now a bass player. And maybe I needed the 40 years to become one. [laughs]

At what point do you feel like you made that transition?

I think it started on the ’94 Floyd tour. That’s when I suddenly started thinking, “Wait a minute, what are you doing here? You should be playing a Precision with a pick.” And then I kept at it. By 2006, the [David Gilmour] On an Island tour … I would say since then I’ve been a grown-up, if you will.“There’s no need for a sixteenth note on the bass anywhere in this music, ever.”

You’ve mentioned retooling your gear specifically to address that sort of deeper, more grown-up tone. And you’ve spoken about a particular instrument that you created—part Jazz Bass and part Hofner.

Bill Nash, who’s a friend and who makes the most beautiful guitars and basses, gave me a Telecaster bass. And it had one of those open [uncovered] pickups on it, but it also had a Jazz pickup. It’s got my Luck and Strange sticker on it, because it’s my Luck and Strange bass, and a stack knob. And the thing was, I was trying to think where to use it. On “The Piper’s Call,” David got ahold of the violin bass and noodled around, and it’s gorgeous stuff. I played a big, rounded Fender part that David told me to. Of course, when it came to rehearsing for the live shows, David said, “Well, obviously you’re doing both parts.” And I thought, “How the hell am I doing that?” Because there’s the Fender part and this nice little “do-do-do” going on top. I tried playing it with a violin bass. That just didn't work. It’s too small, just too insubstantial for me to hold. And it didn’t work on the Fender. So then I thought, “What would David do?” Because he’s really good at coming up with A-team-type solutions for things, like re-tuning his lap steel so he’s got a major and a minor chord. I was trying to think of a version of that, and I said, “Ah-ha! What if I take this Nash bass, and on the top strings, the D and the G, put on flatwounds, and then get a bit of foam and stick it under just the top two strings.”

What I always find interesting when rehearsing with David is what he remembers from bass parts. “You need to play that”—that sort of thing. A lot of the music is so slow and so big and there’s so much space in it. Very often it’s actually the length of the notes rather than how many notes you’re playing that matters more. With David, and this is something I get with the wisdom of years, every note does count. It’s quite funny when I think back to what I used to play in jams with him, like when we did a week of the Division Bell rehearsals. I was still stuck in that thing of playing sixteenth-note parts. It’s just like, “Why?” There’s no need for a sixteenth note on the bass anywhere in this music, ever.

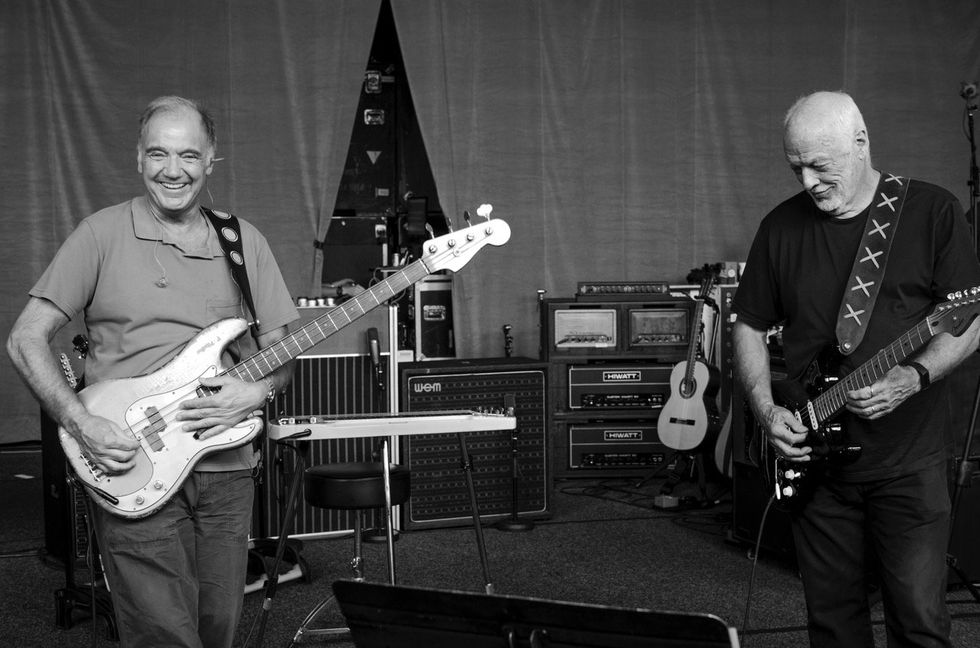

Pratt, at left, alongside Gilmour (center) and drummer Adam Betts play Pink Floyd’s classic “Time” at Madison Square Garden on November 4, 2024.

Photo by Emma Wannie/MSGE

Your career started, essentially, playing in new wave bands and on sessions, including Madonna’s “Like a Prayer.” But now you’re best known for your work with Pink Floyd, Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music, David Gilmour … more atmospheric music. What was that transition like for you?

There’s a quote: “As you live your life, it seems this absolutely chaotic, random set of events. And then when you get towards the end and you look back, it’s like the most beautifully plotted novel.” When I was playing with Icehouse, [frontman] Iva Davies wore his influences on his sleeve: Simple Minds, Bowie, Ferry, which was great stuff. I loved it. So I became versed in that style of playing. When we were making the second album, we got Rhett Davis, who was Roxy Music’s producer, for one of two reasons. Iva sang so much like Bryan Ferry that it was like, “If he’s gonna do Bryan, let’s do this properly.” Or Davis’ gonna go, “Come off it! Be yourself.” Anyway, it was fantastic working with him and we really got on. So it came to pass that I auditioned for Bryan and I got the gig. Even though I’d already worked with Robert Palmer, who was a huge, huge hero, this was different. Working for Bryan was crossing the Rubicon—as big as Bowie, an absolute icon in my head. So anything after that, Pink Floyd, nothing was gonna get bigger anymore. It was like, “This is Bryan fucking Ferry, you know?” Bryan is still my longest working relationship. I’ve been working with Bryan for 40 years.

“Something that I really noticed on the tour is it feels like David now owns his past. He’s not owned by it.”

Focusing on David, who you’ve been working with for 38 years, did that relationship start after he played on Bryan Ferry’s Boys and Girls sessions?

The first thing was, I was playing for Dream Academy and David had produced them. He needed a support band for this one show in Birmingham. It’s quite funny because Nick Laird-Clowes, the main guy from Dream Academy, is this fantastic, enthusiastic character. And he said, “David’s heard your playing. He thinks you’re amazing. He can’t wait to meet you”—which of course was just bollocks. So we get up there in Birmingham. I’m terrified. And he said, “David’s just dying to meet you.” And I went in and just stood in his dressing room and it was awful. We both stood there with nothing to say until one of us had to walk away. David, being the ranking officer, got to be the one who walked away. And that was the end of it. But I got to spend a bit of time with him with Bryan, which sort of loosened things up a bit. And I started just seeing him out and about. I think I was just getting invited to better parties. [laughs]

So, I went on holiday to Thailand and I came back and there’s all these messages from David. The first one saying hi, he was doing an Amnesty International concert, the Secret Policeman’s Ball, and he wanted me to play with him and Kate Bush. And there’s another message and another message. “Hi Guy, just wondered, it’s next week you know.” And then, of course, he had to get someone else. I’m like, “My god, that was my one shot.”

A while later, David, Rick [Floyd keyboardist Richard Wright], and Nick were saying they were doing a new Pink Floyd album, and I didn’t think any more about it until I got a phone call from L.A., and it’s David going, “Hi. We’re putting Pink Floyd back together.” He said, the tour was gonna be a year, and would I be interested and available? So I went, “Yes!” And he said, “Oh, not working much, then?” And that started our relationship of him ribbing me and me constantly falling for it. That’s been the hallmark of our relationship for the last 38 years.David’s latest solo album, Luck and Strange, seems perhaps more organic than most of the Pink Floyd albums he’s helmed and his earlier solo work. After all these years working with him, you’re in a good position to comment on that. Is there something different that you find within it?

I know what you mean. There’s definitely been something different about this album, about the way it’s been received, about the tour. It was hugely successful in a way that some people’s solo records could only dream of. On An Island is where it started. There are quite a few people now who will point to the song “On An Island”’s solo as on a par with “Comfortably Numb.” But there’s something about this one, a sound. And a lot of that’s to do with Charlie Andrew and Matt Glasbey's engineering. It feels of a piece. And something that I really noticed on the tour is it feels like David now owns his past. He’s not owned by it. And for me, if you look at the set list, well over half is songs I played on. It’s always been quite piecemeal with David’s other records. I’ve gone in for a couple of days here and there, but David’s played quite a lot of bass himself. He’s brilliant.

With David, there is always this thing where suddenly he’s puttering about, then puttering about a bit more, and then suddenly “bam,” we’re in gear—there’s an album. We did a whole week in British Grove Studios with Steve Gadd, which was amazing. His playing wounds you, gets you in the chest. It’s so light and so potent. It’s just gorgeous. Why I think he was such a great call is that, in all my years with all those elite drummers, Steve is the closest to Nick.

Pratt and Gilmour share a smile during the Luck and Strange tour rehearsals.

Photo by Paul McManus

I think Nick is a vastly underappreciated drummer. I love his playing. It’s so conversational.

That’s a great way of putting it. Yes, he absolutely was underappreciated, in the same way, if you remember years ago, that David was actually a somewhat underrated guitarist. And you know, I’ve noticed that with all the top drummers I talk to now, everyone’s like, “Nick Mason, man!” It seems like he can take his playing anywhere he wants to and feel utterly relaxed at the same time. And what’s been amazing with the Saucers, because we’re doing all that early stuff, is it’s so crazy, manic. I get worried for him, you know. “Should someone have a heart monitor on him or something?” But that stuff doesn’t seem to bother him at all. It’s fantastic.

I need to ask, what was it like playing onstage in Pompeii? A beautiful setting; what an extraordinary experience.

At the risk of sounding unbearably smug. I’m one of the small group of people that played Pompeii twice. With David, we were on a stage at the end of the amphitheater. It was so small, we just had the screen, there was no sides, there was no roof; it was mad. There was only 1,800 people, so it was like a club gig. It was fantastic. And with the Saucers, we played at the Teatro, which is the theater, which is really small but lovely, in a different part of the complex, but it’s still Pompeii. But we did it in the middle of an absolutely horrendous heatwave. So it was nearly 40 degrees [104 Fahrenheit] and we couldn’t sound check. The poor crew were wilting and we basically just had to sit on the bus and then went in through the audience, did the show, and left. Whereas with David, we had Mary Beard, the great historian with us. We were there for four days.

“At the risk of sounding unbearably smug, I’m one of the small group of people that have played Pompeii twice.”

You’ve done extensive film and television work. How did you get into that?

I love working on film. I used to work with Michael Kamen a lot. I love working to picture. I also love that it is a great way of writing music and not having to finish it. Usually, you come up with a great piece of music and, okay, well now I need a verse, now I need a bridge. Whereas with a film score, it’s like this character needs something. That’s it. Then you move on. TV music is like the demo version of film music. No one expects a real orchestra, so you’re kind of going, if this was a film, the music would be doing this. Of course, now everyone’s got massive screens and 5.1, so the stakes are higher.

That came about through me hanging about at the Groucho Club, which is this big media arts club in London, and just telling people I wanted to do film music. The first thing I did was a documentary … on the Roswell autopsy. That was completely fake, but it was perfect. This was was mid-’90s, so it was the whole electronica and ambient house, chill, Orb scene. So perfect for that sort of film. But then I got this fantastic gig, which I’m still really proud of, which is this TV series, Spaced, with the director Edgar Wright, with Simon Pegg and Nick Frost starring in it. Edgar, if you know from his films, is such a film nerd, so literally everything is a reference. It was brilliant. I had to do Kubrick. There’s a bit of what looks like a zombie movie, so I had to kind of write a John Carpenter score.

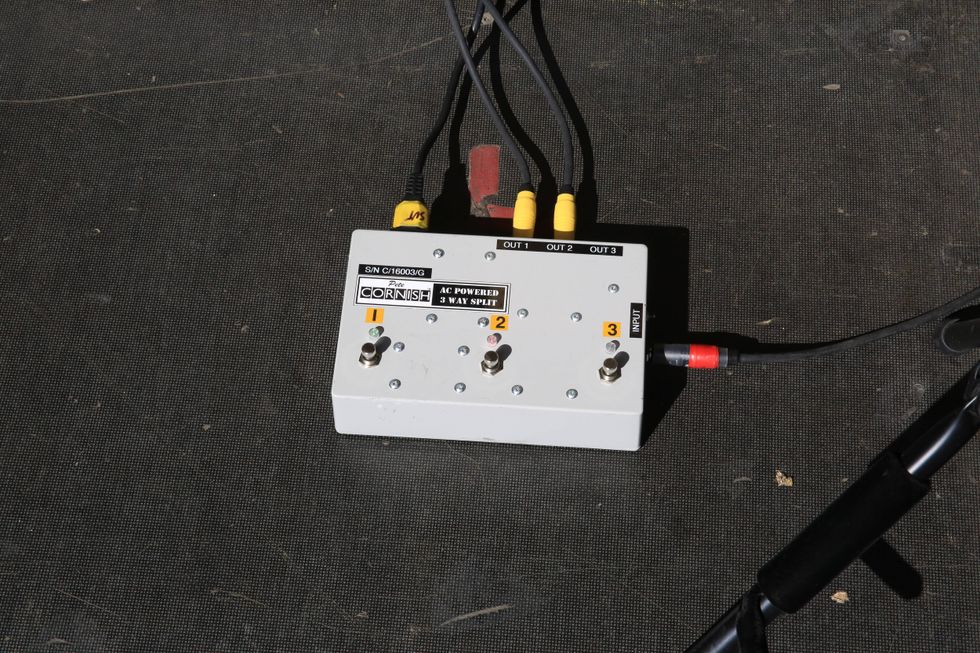

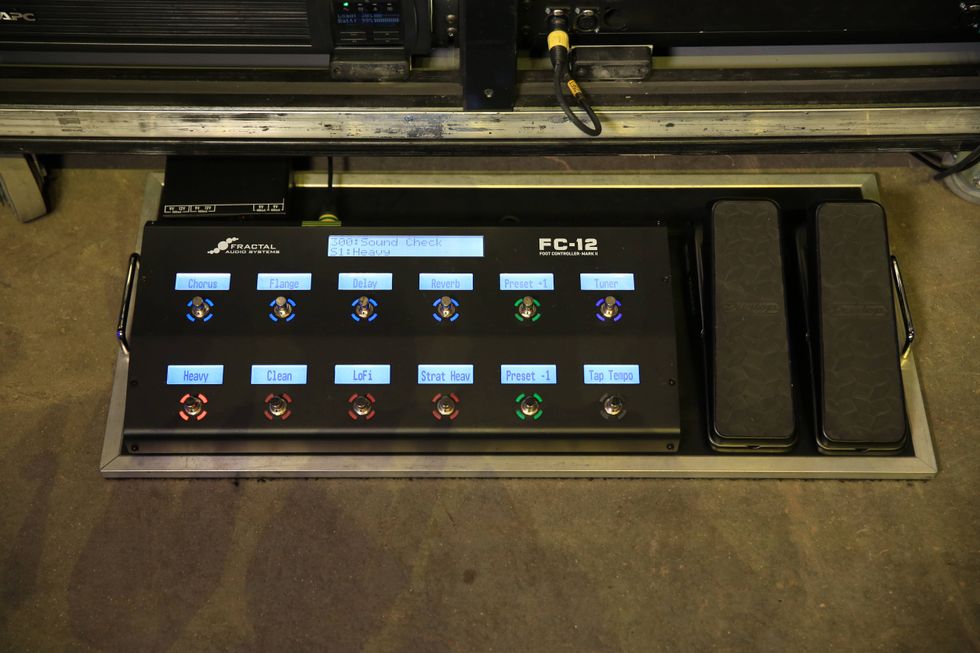

To recreate the sounds from the Gilmour, Floyd, Roxy, and Ferry catalog, Pratt employs this extensive pedalboard.

You’re also a podcaster, and your Rockonteurs, with Gary Kemp, is very entertaining, with its “behind the music” approach

The podcast came about literally from the first Saucer Full of Secrets tour. We had this tour bus and this is long enough ago that the bus actually had a DVD player. And I brought a box set of The Old Grey Whistle Test, which is the legendary 1970s English music TV show. We used to watch it on the bus, and it was just brilliant. Everyone had an opinion about every act that was on, or a story. Of course, half the time Nick knew them and he’d have some great stories and we’d be talking about it, and someone said, “Man, we should do a podcast.”

We didn’t know it was gonna fly at all. We had this address book, we just asked a few mates to come and do it. And it just became a thing, you know, and it’s really nice because no matter how well I know the artists, we always get something I’ve never heard. We had a couple of scoops. My favorite got on the front page of The Times and The Guardian, when Whispering Bob Harris, who used to present The Old Grey Whistle Test, told us that Nixon asked Elvis to spy on John Lennon.“All musicians have really funny stories because it’s a kind of preposterous life we lead.”

You also do a one man bass-and-jokes comedy shows?

All musicians have really funny stories because it’s a kind of preposterous life we lead. So I started telling them, with my bass in hand, and it did really well. So then I had to write a book [My Bass and Other Animals]. I went around the world with it, been to Australia four times.

It’s something I really like, because I knew I was never going to do a solo musical thing. I really love the job of the bass. I mean, I’m very happy being the center of attention at a table or whatever. But in a musical set, I really love that thing of playing the instrument that just makes everyone else work. But there’s a syndrome I call “sideman bitterness” that I’ve seen happen a lot. When people start getting to their 50s or whatever, it’s like, “Where’s my shit?” And so I thought, “Well, I need to do something on my own to avoid that.”

Another thing is that when you get up on stage with Bryan Ferry and play “Love Is the Drug,” you’ve got a pretty good idea of how it’s going to go. With David Gilmour, when you play “Wish You Were Here,” you’ve got a pretty good idea of it. What I love with stand-up is that I get up there and people don’t really know what I’m gonna do. They don’t really know what they’ve come to see. I’m not entirely sure about it. It’s completely fresh, in the moment. And I think that’s something that might have made me a better bass player, in a way. Because now I’ve had it all on my shoulders, so it’s really nice to go back and just be the guy playing bass.YouTube It

David Gilmour is Guy Pratt and Gary Kemp’s guest on this episode of the Rockonteurs podcast.