Daron Malakian doesn’t believe everything he writes should be recorded right away, and he doesn’t craft songs in front of a computer with a DAW. “I guess I’m old school that way,” he confesses. “I just sit with my guitar on my couch, and if I come up with a good idea I record it on my [smartphone] voice memo.” Over time, he’ll go back to those ideas, repeatedly, whenever he picks up his guitar. “I entertain myself that way, playing with it like a toy, and then, sometimes years down the line, I record it.”

-YouTube

Whether with System of a Down or his own band Scars on Broadway, Malakian’s melting-pot songwriting alchemy draws as much from his Eastern (Armenian) heritage as it does his Western (American) influences. This unforced approach to songcraft has been at the heart of his success ever since he burst onto the scene with System of a Down’s eponymous debut in 1998. System released Toxicity in 2001, featuring their controversial, breakout single “Chop Suey!” and the epic, requiem for life’s meaning, “Aerials.” In 2005, they released two albums, Mezmerize and Hypnotize, the former featuring “B.Y.O.B,” which earned them a Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock Performance. For a band that only released five full-length albums between 1998 and 2005—three of which debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200—System of a Down sure left an indelible imprint on hard rock and heavy metal with their socially provocative lyrics and drop-tuned guitar manifestos.

Malakian launched Scars on Broadway and released their self-titled debut in 2008 largely because System had become inactive. In 2018, he issued Dictator, simultaneously rebranding the outfit as Daron Malakian and Scars on Broadway, citing the fact that he envisioned a rotating cast of musicians rather than a singular lineup. The third Scars album, Addicted to the Violence, dropped on July 18. On each record, Scars delivers lyrics that are in line with the social themes that fuel System’s worldview. Musically, however, Malakian doesn’t seem bound by genres or interested in recreating the success of past endeavors. The binding ingredient in his sound is simply to be honest as an artist.

“I have to be open to using whatever colors the song is asking for.”

“I’m going to make a Beatles reference, but I always want to be careful,” he clarifies. “I’m not putting myself on their level, but when you listen to the Beatles and you hear, [sings] ‘Michelle, ma belle…,’ then ‘Helter Skelter,’ then ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,’ it shares the same DNA, but it’s so different stylistically. I’m not saying I achieved that on the same level, but I like artists that go through phases.” He cites Iggy Pop’s The Idiot, produced by David Bowie, as a prime example. “When you listen to that album it’s just so different from the Stooges. Having said that, the Ramones kept the same formula, and I freaking love the Ramones, so nothing against those guys, but it’s not what I do.”

Take “The Shame Game” on Addicted to the Violence. After the up-tempo, aggressive, one-two-three socio-political punch of “Killing Spree,” “Satan Hussein,” and “Done Me Wrong,” the mid-tempo song drops in, grabbing the listener’s attention with a dark, foreboding guitar part that completely shifts the tenor of the album, from heavy-on-the-riffs cultural insanity to mid-tempo atmospheric musical empathy. It’s an epic detour that enhances not only the track listing but exemplifies the yin and yang of Malakian’s songwriting, whether it’s the back and forth between mid- and up-tempo numbers or the amalgam of emotions and influences present in any given tune. Most importantly, “The Shame Game” reflects his patience when it comes to crafting a song, and is a great example of how Malakian can sometimes spend years toying with an idea.

“I used to start that song with the vocals: [sings] ‘Ain’t no shame in your game,’ but I was never really happy with it,” he explains. “I even recorded it that way when I first started working on this album during the pandemic.” One day, while sitting with his guitar in his living room, the intro 6-string part spilled out. “I didn’t even really come up with it for ‘Shame Game,’” Malakian admits. “But when I put it there, it completed the song. And that only happened years after I wrote the bulk of the tune.”

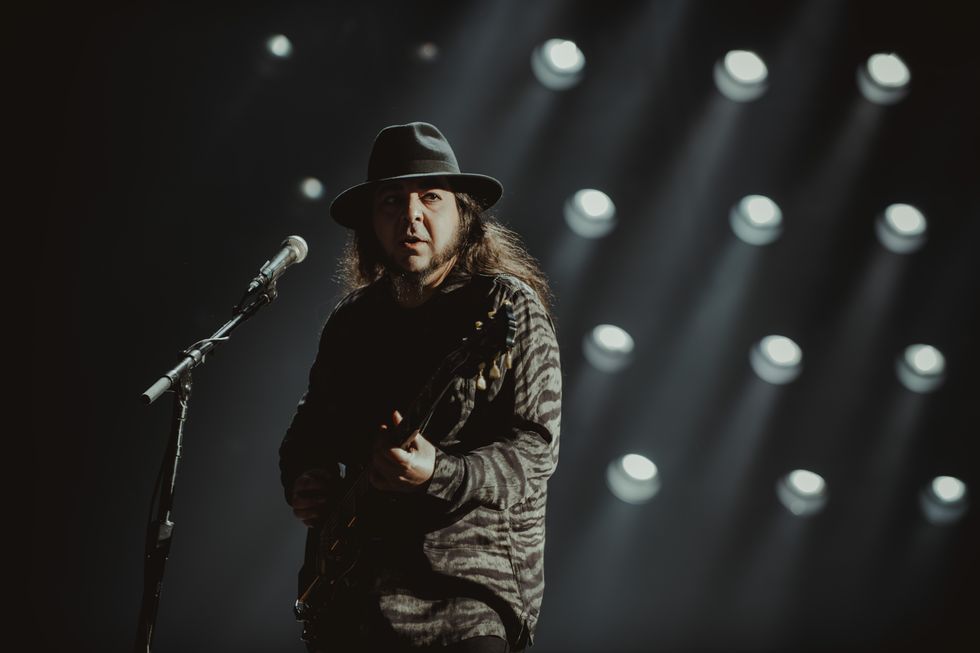

Malakian plays his 1962 Gibson Les Paul SG Standard in this concert photo. His other main axe is a 1968 Gibson ES-335 that, he says, “just explodes sonically, so I often use that for my heavy tone.”

Ekaterina Gorbacheva

Malakian practices this unobtrusive approach to songcraft not by imposing his ego onto his ideas, but rather by allowing the song to tell him what it needs. “If I didn’t have moments like ‘Shame Game’ or ‘Addicted to the Violence’ or ‘You Destroy You,’ it wouldn’t feel like me,” he explains, citing three songs from his new album that most embody his Armenian upbringing and broad musical palette. “I can’t just pick three colors and say, ‘I’m only going to use these colors for this piece of work.’ I have to be open to using whatever colors the song is asking for. Sometimes it’s going to be heavy and you’re going to want to mosh, sometimes it’s going to be emotional and you’ll want to sing along, and sometimes you’re going to laugh because it’s freaking ridiculous and funny and kind of stupid. And those are all the sides of human emotion I’ve always tried to express in my writing.”

Malakian’s view is that he is merely channeling whatever it is the universe has to offer, and his lack of an agenda creates the necessary space for the creative juices to flow. It’s one of the reasons he gives the songwriting process time. “I just let things happen very naturally, and whatever sticks with me, sticks with me,” he attests. “Sometimes I don’t even feel responsible for it, like, ‘How the fuck did that just come out of me?’ Everything I do is subconscious.” When System first came out, for example, he says people would often focus on the Armenian influence in their music. “We were like, ‘We’re really not trying to write like that.’ It’s just part of the culture we’ve been around, so it’s bleeding into what we’re doing without us really trying to make that happen. It just happens.”

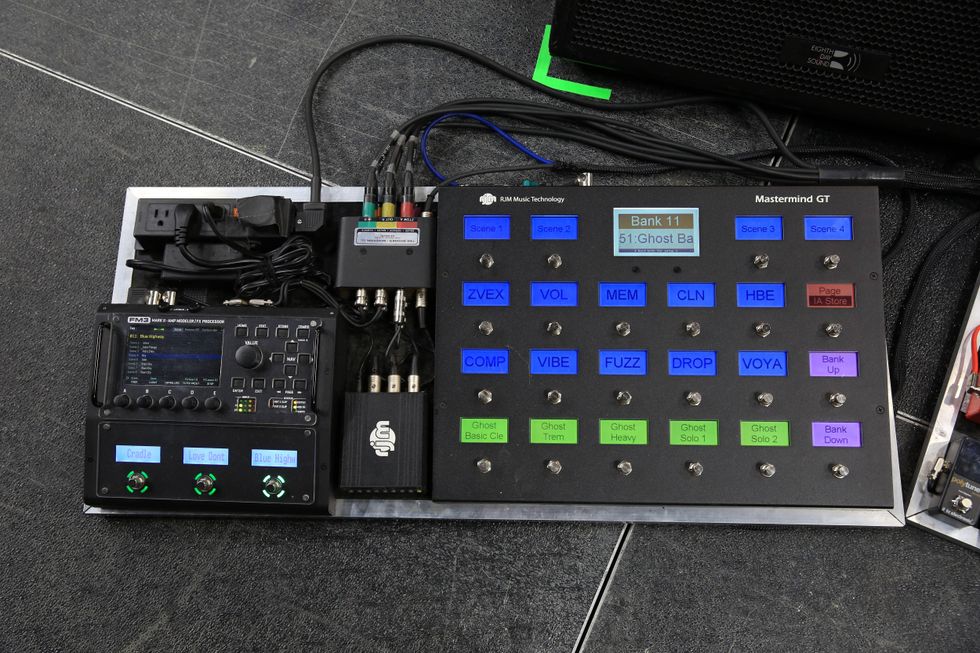

Daron Malakian’s Gear

Guitars

1962 Gibson Les Paul SG Standard

1968 Gibson ES-335

Amp

Dave Friedman-modded ’70s Marshall JMP100

Effects

Boss DD-6 Digital Delay

MXR M101 Phase 90

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2215 Skinny Top Heavy Bottom (.010–.052)

Jim Dunlop Delrin Triangle .96 mm picks

Malakian grew up in Los Angeles and went to an Armenian private school, where he also attended church. It was there he first got into music, via singing, long before picking up a guitar. “I would sing Armenian church-chant kinds of things,” he recalls. He subsequently wrote a lot of the melodies in System of a Down (“Serj [Tankian, System lead vocalist] might be singing them, but I wrote a lot of those vocal lines”), and is the main lyricist and singer in Scars. His family lived in a small apartment when he was an adolescent, so he couldn’t have any loud instruments. He actually wanted to be a drummer, but didn’t get his first instrument until his family moved into a house when he was 11, and he finally got his own bedroom. “Guitar happened by accident,” he says. “I’m happy that it happened, but my parents didn’t buy me a drum set because you couldn’t turn it off. [laughs] To this day, I’m more interested in vocalists and drummers than I am guitar players.”

“I actually have to stretch myself to get bluesy.”When Malakian’s parents did eventually buy him a small amplifier and a guitar, he says, “I was like, ‘Alright, this is what I’ve got. Let me see what I can do with this thing.’” He spent hours in his room playing, but instead of focusing on guitar chops, songwriting became his passion. “I found my own voice through writing songs,” he recalls. He’s so song-driven, in fact, that he wrote much of the first Scars record primarily using synthesizers and drum machines, which imbued the early demos with “electronic-goth vibes.” When he assembled a band, he introduced those songs to the unit with his guitar. “Songs like ‘Funny,’ ‘They Say,’ ‘Whoring Streets’ [from Scars on Broadway], and even ‘Guns Are Loaded’ [fromDictator] were all written on synthesizers before becoming guitar-driven rock songs,” he admits. When he transitioned them to guitar for band rehearsals, he says, “I found myself playing things that I wouldn’t have come up with had I come up with them on the guitar.”

When it comes to songwriting, Malakian is ready to shake hands with the universe and just let it flow.

The solo in “Done Me Wrong” is an example of how the Armenian influence can seep into Malakian’s songwriting with a bit more intentionality, and that it’s not necessarily the guitar that needs to be the focal point of his tunes, even when soloing. “The solo that you hear in the middle of the song, that keyboard, synthesizer-style, is the type of solo that you’ll hear in Armenian wedding-pop-dance music,” he explains. “I co-wrote that song with my guitar player, Orbel Babayan, and it drives very much like Deep Purple in the way that the rhythm moves. And like Deep Purple, we wanted that kind of solo, not in a neoclassical way, but more like what we call ‘Rabiz’ in Armenian music.”

Malakian says that blues-rock-based riffs and motifs don’t come as naturally to him as they would to someone who was raised on American rock ’n’ roll. Conversely, styles like Rabiz do come more naturally to him than they might to your average Westerner. “I actually have to stretch myself to get bluesy,” he admits. “That’s just because of where my family comes from and the community that I grew up in. But I was born and raised in the United States, so I was influenced by rock, metal, and pop radio, too.”

“I always tell people when you put out an album it’s forever.”

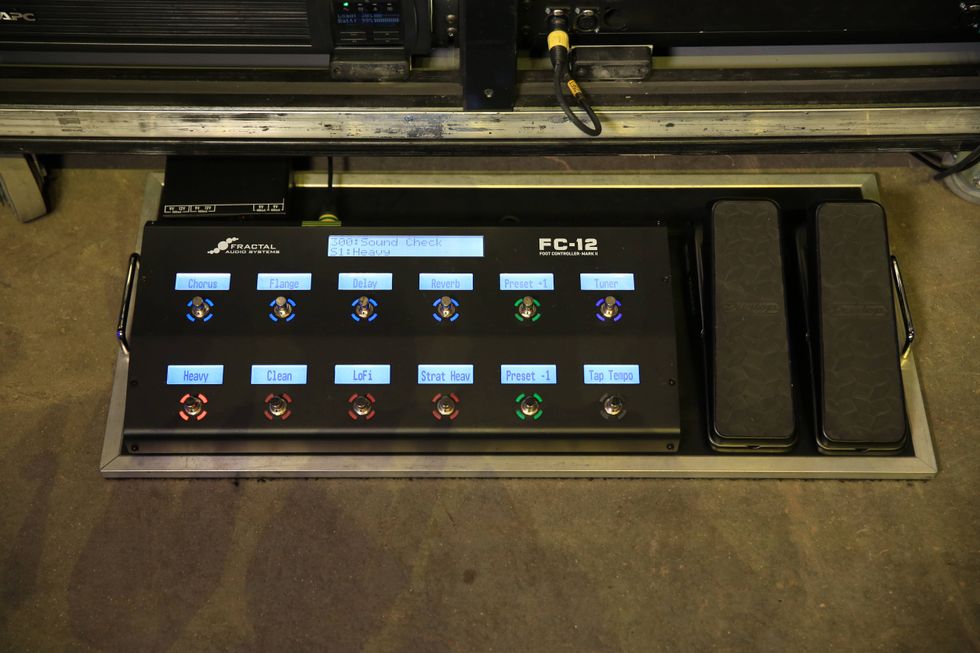

Ever since System’s Mezmerize and Hypnotize albums, Malakian has pretty much kept the same “heavy” guitar tone for recording. His main amp is a Dave Friedman-modded Marshall 100-watt JMP100 from the ’70s. For guitars, he relies on his 1962 Gibson Les Paul SG Standard and a 1968 Gibson ES-335. “We had the fires in L.A. back in January, and I had to evacuate,” he recalls. “I left all my guitars except for those two. I cannot replace them.” For recording, he generally stacks those guitars on top of each other. “The semi-hollowbody just explodes sonically, so I often use that for my heavy tone.” During System’s heyday, he layered a lot of guitars on top of each other, but with Scars, he doesn’t. “On this record, I didn’t really bust out a million guitars,” he says of Addicted to the Violence. He doesn’t employ many effects, either. “Sometimes I’ll use a phaser or a delay, but I’ve never been that crazy about using effects.” A hallmark of Malakian’s guitar sound is the crispness and crunchiness of his rhythm tone, a testament to these vintage axes and his minimalist approach.

Malakian’s early relationship with Rick Rubin, with whom he co-produced System of a Down’s albums, also had a significant impact on his songwriting and record-making ethos. “I’ve never had another producer aside from Rick Rubin, so his production style is what I bring to my mindset—it’s not technical at all,” he explains. “He’s someone who guides you on a journey and gives you advice.”

When Malakian wrote “Lost in Hollywood” [from Mezmerize] and brought the song to the band, Rubin looked at him and said, “It’s good, but it’s not finished.” Malakian recalls, “I thought it was finished, but that night I got home and that whole middle section came out of me. [sings] “I was standing on the wall, feeling 10 feet tall…’ It came out of nowhere.” Now, he says, he can’t even imagine the song without that part. “It’s the best part of the whole fucking song,” he attests. “Did he turn a knob? Did he fine-tune my guitar sound? No, but he made my song better just by giving me a little nudge and saying, ‘I don’t think it’s finished.’ I hear some people have experiences with Rick and they’re like, ‘He didn’t do anything.’ If you want your hand held through the whole fucking process and someone to sit there to be your motivation while you’re doing your guitar tracks, he’s not that guy.”

At this point in his career, Malakian has the luxury of not having to shoehorn his creativity into record company deadlines or marketing campaigns. He likens his artistic mindset, which leans towards capturing moments of divine inspiration, to preparing a meal. “I always tell people that when you put out an album it’s forever,” he says. “And because it’s forever, I don’t mind taking forever to finish that thing that’s going to be forever. You don’t serve a meal until it’s done cooking. And I’m in no rush.” He laughs. “It’s done when it’s done, and it will taste better to you that way.”

YouTube

Listen to Daron Malakian and Scars on Broadway’s Addicted to the Violence in its entirety.

Bettencourt onstage with the Dark Horse at the Motocultor Festival in Carhaix, France, on August 23, 2005 Sarah "Sartemys" Leclerc

Bettencourt onstage with the Dark Horse at the Motocultor Festival in Carhaix, France, on August 23, 2005 Sarah "Sartemys" Leclerc