Any list of great British songwriters, from Lennon/McCartney, Ray Davies, and Pete Townshend to Elvis Costello, must contain Richard Thompson. But any discussion of England’s most impressive, identifiable guitar players (be they Clapton, Beck, Page, or Mick Taylor) also needs to include Thompson. And it’s a coin toss which 6-string he excels at more—acoustic or electric.

Richard Thompson - "Singapore Sadie"

Today the 75-year-old boasts a loyal, nay, rabid, multi-generational following, for whom originals like “Tear-Stained Letter,” “1952 Vincent Black Lightning,” and the much covered “Dimming of the Day” are classics. In 2011, Thompson received the OBE, Order of the British Empire, for his “singular and substantial contribution to music.”

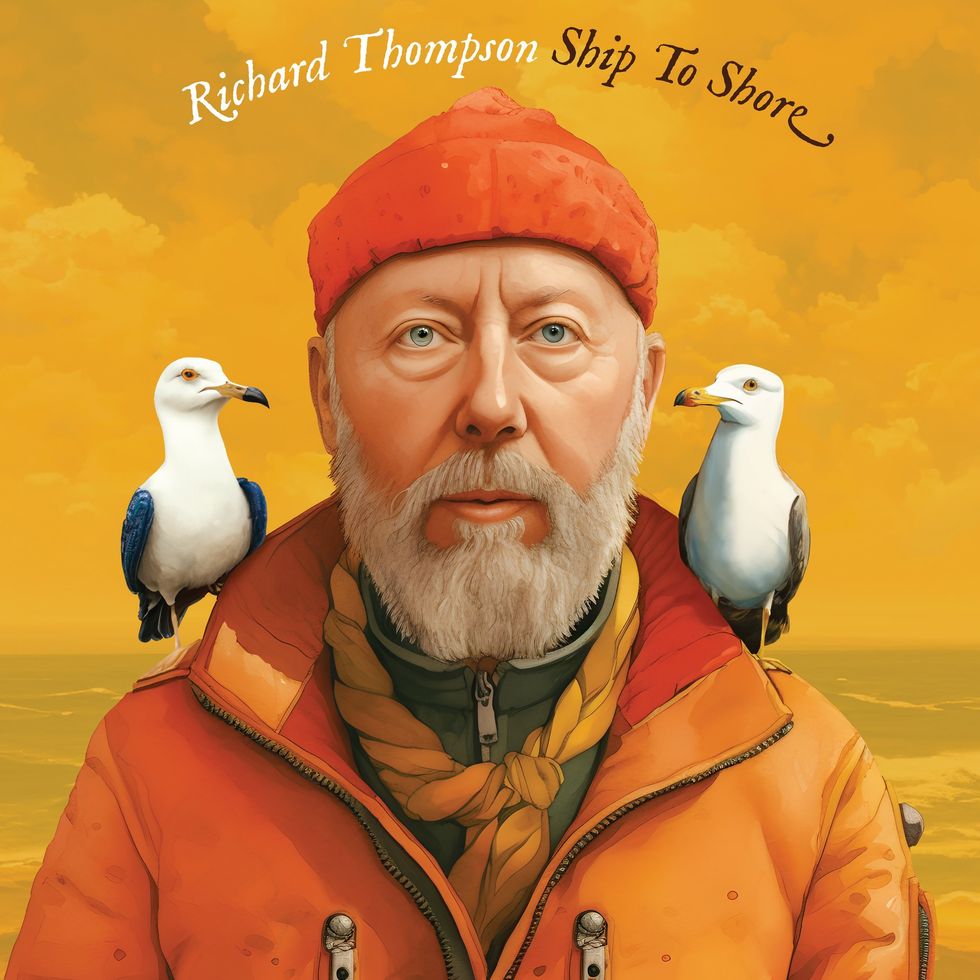

If the “singer-songwriter” ID evokes an image of dead-end humming and strumming, Thompson’s ever-stunning guitar work demands taking notice. That’s been the case since his late-’60s folk-rock band, Fairport Convention, across numerous solo albums, live and studio, and collaborations with former wife Linda Thompson, and is clearly evident on his latest, Ship to Shore. As usual, moods and attitudes can be dark without being ghoulish (“If you should dream the dreams I dream / You’d never sleep again”), funny without getting cute (“A splash of Opium between her knees / Shops ’til she drops like it’s a disease”); cynical one moment, romantic the next—but most of all intelligent without being stuffy.

His Frets and Refrains guitar and songwriting retreat marks its 12th anniversary in July 2024, of which Thompson says, “It’s one of the high points of my year.”

Ship to Shore closes with an atypically straightforward ode to life on the road, “We Roll” (“We’re in this thing together, and we roll”)—somewhere on the sentimental scale between Willie’s “On the Road Again” and CCR’s “Travelin’ Band.” “You go on the road for a month and get home,” he reflects, “and even though it was musically wonderful, you’re a bit knackered. But after a week you think, ‘Can’t wait to get out there again.’ I just like playing live, and I love the idea of putting something across to an audience who’s appreciating what I’m trying to do. It’s a great feeling.”

Richard Thompson's Gear

Thompson holds an annual guitar and songwriting retreat called Frets and Refrains, which celebrates its 12th anniversary this July.

Photo by David Kaptein

Guitars

- Lowden Richard Thompson Signature with Sunrise pickup system

- Custom Stratocaster with early Rio Grande pickups

- Custom 12-string Telecaster

- ’66 Fender Stratocaster

Amps

- Ridge Farm Gas Cooker tube preamp (for acoustics)

- Divided by 13 FTR-37 with 2x12 cab (for electrics)

- Fender ’65 Deluxe Reverbs (for electrics)

Effects

For acoustics:

- Analog delay

- Vibrato pedal

For electrics:

- Divided by 13 Switchazel A/B box

- Fulltone OCD

- Fulltone tremolo

- Catalinbread Echorec

- Analog Man Sweet Sound MojoVibe

- EHX POG

- Ernie Ball volume pedal

- TC Electronic tuner

Strings & Picks

- Elixir Acoustic 80/20 Bronze (.012–.053)

- Elixir hybrid set (.008–.042) (for electrics)

For a certain generation of American musicians, their “Big Bang,” enticing them to take up guitar, was the Beatles’ appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show in February ’64. But that wasn’t broadcast in the U.K. What was your Big Bang?

Richard Thompson: I had a sister who was five years older than me. When I was 5 and she was 10, she had “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley. Subsequently, she had Gene Vincent records, Jerry Lee Lewis, and was a huge Buddy Holly fan. That was kind of a moment right there. In the U.K., you had the Shadows with Hank Marvin, who got a fantastic tone out of a Fender Stratocaster. Their records still sound amazing today. Hearing their first big hit, “Apache,” was the kind of moment where you say, “Okay, we have to start playing guitar and form a band.” They were kind of a Big Bang moment. So at about 11, I was in an instrumental band.

Then there were more subtle things. With the R&B bands around London, the Cyril Davies R&B All-Stars were a very seminal band. Some of the Stones kind of went through that band; Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, same thing. Just being in London, you could hear jazz, country music, folk music, pop, R&B, any night of the week. That was a great experience.

It seems that, although the Beatles were a big deal, sometimes American musicians wanted to be more like the Rolling Stones—a certain generation did, anyway—who were a very good band, but a bit untogether for the most part. I thought in the U.K. there were better blues and R&B musicians.

People in America don’t realize how big the Shadows were globally.

Thompson: They were huge in Scandinavia, Germany, Japan, Australia. In Canada, Neil Young was a big Shadows fan. What amazes me is they were recording at EMI, basically the same studio that the Beatles were using a year or two later, and their records sound so good. The bass, the drums, everything sounds great. Hank Marvin was playing a Stratocaster through an AC15 or AC30 with a Meazzi tape echo, and just sounded brilliant. If you listen to an equivalent Ventures record from the same era, it sounds trashy and not well recorded.

“A lot of British traditional music wasn’t accompanied at all; it was just vocals. So there’s a bit of a mystery of how you harmonize it.”

Besides James Burton, were you influenced by any other hardcore country players?

Thompson: I love all that stuff. I fancy I might have been one of the earlier people in Britain to listen to imported country music. It was very unfashionable in the U.K. In Ireland and Scotland it was popular, but very hokey. I’d go to the import shop and find these really great records, like a pedal steel guitar compilation on Starday. Similarly, there’s a great country-jazz guitar compilation with people like Hank Garland and Thumbs Carllile. As for influential, it helped me to not sound like the blues guitarists who were around at the time. Players like James Burton were bending notes in more of a country way, which I thought was interesting, in some ways more relevant. I thought that the blues field when I was 18—there’s Peter Green, Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor—these U.K. blues guitarists were kind of slavishly imitating Buddy Guy and Otis Rush. I wanted to be a different kind of guitar player. So I took influence more from British traditional music, Celtic music, and country music.

In terms of rock guitarists who weren’t relying on blues licks, Jerry Garcia and David Lindley come to mind. But there aren’t a lot.

Thompson: To me, there’s a lot of mediocre white blues guitar players. They kind of claim the blues as their cultural heritage; that’s a bit iffy. The yardstick for me is, are they contributing anything new, and are they as good or better than the people they base their style on? Often the case is no. There are exceptions, like David Lindley and Ry Cooder, who are wonderful musicians. If you’re a great musician, you’re a great musician. If you’re saying something new or different, I think that’s a real achievement.

On Ship to Shore, Thompson explores moods ranging from dark to funny to cynical to romantic.

Were you always playing acoustic folk music and electric rock at the same time?

Thompson: Absolutely. Being in London was great for hearing those kinds of music. At folk clubs, you’d see really good acoustic guitar players, like Davy Graham, Bert Jansch, and Martin Carthy. I had a parallel interest in electric guitar as well. I suppose at the time it was more relevant, because you wanted to be a good contributor to a band.

Were you already experimenting in open tunings?

Thompson: I was, yeah. I was trying to find more elusive kinds of things, like Clarence Ashley doing old-timey music on banjo. I thought he must be tuned to a modal chord. Turns out he wasn’t, but it sounded like a suspended-4 tuning. I kind of discovered DADGAD on my own, not realizing that Davy Graham had discovered it about 10 years before I did. There are types of tunings Martin Carthy came up with, keeping the indeterminate atmosphere of a traditional song, where you don’t really know where the key is. You don’t want to nail it down; you’re killing the mood of the song. It’s nice to come upon a tuning where it sounds a bit more unresolved—not sure if it’s in D, G, or A. You can have the kind of chord shapes that suggest it’s in all three keys at once. A lot of British traditional music wasn’t accompanied at all; it was just vocals. So there’s a bit of a mystery of how you harmonize it. Having more ambiguous chords—suspended 2 or 4—helps to somehow convey the song in a more elusive way.

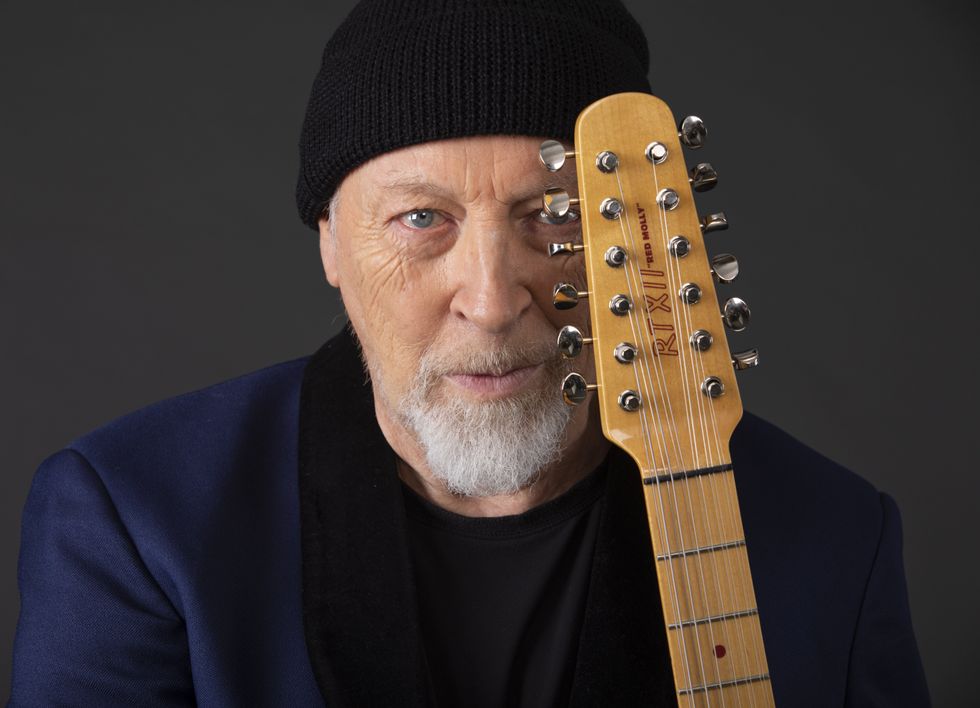

Your acoustic playing and electric playing don’t resemble each other in the way that a lot of players’ styles overlap.

Thompson: I’m playing fingerstyle on acoustic and electric. I don’t tend to strum too much on either instrument. I do more three-note clusters using hybrid picking. On acoustic, I’m just trying to accompany a song—whatever that requires. But they are different instruments, and I do approach them differently. I really developed my acoustic playing in the late ’70s, when I started to do solo gigs and wanted to get a bigger sound. So I started to use opening tunings and tried to develop the hybrid picking, to really try to sound almost like two guitar players, where you’re accompanying but still playing melodic figures over the top. On electric, I’ve got the luxury of having people hold down the rhythm and hold down the harmony, so I’m freer to play more single-note stuff and go where the music takes me. On acoustic, I’m a bit more chained down to what’s achievable as a soloist and what works as accompaniment.

Over the years, Thompson has mastered his sound on acoustic and electric, both of which he plays with a hybrid style of picking.

Photo by Matt Condon

Particularly on electric, you sometimes get very angular, aggressive, and even dissonant—yet you’re still categorized as folk.

Thompson: Yeah, usually [laughs]. I think I play the sum of my influences. Since I was a teenager, I listened to a lot of classical music. I started with the impressionist composers, like Ravel and Debussy. Then I worked my way backwards and forwards. Grabbing a bit of harmony from Stravinsky or Bach, or a kind of strange chromatic thing from Schoenberg is kind of normal within a folk framework, extending it.

On Fairport Convention’s third album, Unhalfbricking, we did a more extended song, “A Sailor’s Life.” It was a traditional song, but we brought it up to date. We decided to do more of that on the next album, Liege & Lief. Then I continued to do it as a solo artist. And I’m still there; it’s basically what I’m doing. If you have a strong base—I think of my base as being kind of Celtic traditional music—then I think you can extend in any direction. Remember, The Rite of Spring by Stravinsky is more than 100 years old. What we think of as dissonant should be acceptable in music in general—not just “that weird stuff.” That’s a long time to be weird [laughs]. As John Cage says, if it sounds dissonant, keep playing it ’til it sounds normal.

An extreme example of your “out there” side is your work with Henry Kaiser.

Thompson: I think he said once that his ambition was to make music that sounds like it’s from another planet. I think he achieves that [laughs]. His music is challenging, and he likes it that way. He’s starting out with some of the more discordant strains of 20th-century music. He’s an original, and really experimental, and he’s collaborated with interesting people. He went to Madagascar and to Scandinavia with David Lindley, and has a Miles Davis tribute band. His video shows are really great; the tribute to Lindley was lovely. Not enough people know about Lindley. Such a wonderful musician and a great character, too. Sometimes he’d phone me, and he’d either be himself or James Stewart or a Rastafarian—totally convincing. A fascinating human being and a really great musician.

What input did you have into your Lowden signature acoustic model?

Thompson: It’s my design, my wood choice: ziricote back and sides and a cedar top. It’s kind of loud, punchy, even-toned, and at the same time quite sweet-sounding. It’s got really good highs and lows. I’m very happy with it.

Lowden is achieving a high consistency—which I can’t say about every guitar manufacturer. I’ve got an S-32 and a Baby Lowden, which is wonderful, and a really interesting electric GL-10. It’s a solidbody electric, but the fretboard is the same as an acoustic. For an acoustic player to go electric, it’s a wonderful solution.

“What we think of as dissonant should be acceptable in music in general—not just ‘that weird stuff.’ That’s a long time to be weird.”

I’ve used a Sunrise pickup made by Jim Kaufman for about 35 years, and I’ve got a little condenser mic that sits inside the soundhole. So it’s two acoustic channels, and I put that into a Ridge Farm Gas Cooker tube preamp that I take on the road. That really warms up the signal. So the basic sound coming off the stage is the same every night.

You’ve been playing a red “parts” Strat for several years.

Thompson: My guitar tech, Bobby Eichorn, got that red Strat for me—which is fiesta red faded to kind of coral. The body and neck and pickups, which might be Santa Fe, are all from various places. It plays really well and sounds really good. Onstage, I use a Divided by 13 amp—which is sort of like a Fender circuit and a Vox circuit, and you can blend them. Mismatched speakers: Celestion Blue and Celestion Vintage 30. Ooh, I love talking technical [laughs]. In the studio, I use smaller amps, like an AC15 Vox or Fender Pro Reverb or Deluxe. I also use Headstrong amps with Celestions—basically a Princeton with a larger, 12" speaker.

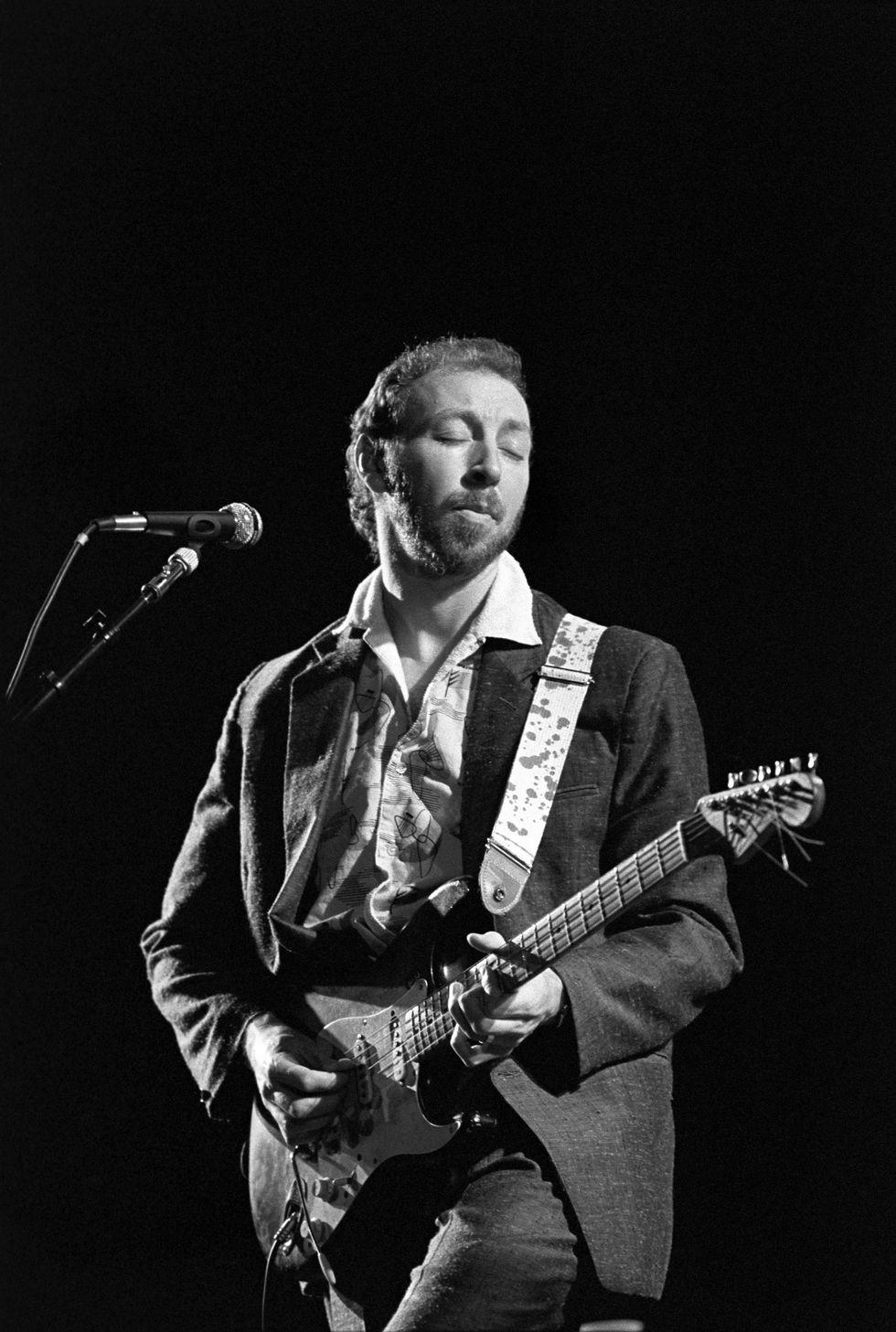

Richard Thompson performs at the Beacon Theatre in New York City on April 20, 1985.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

In an online interview, record producer Val Garay, talking about Linda Ronstadt as an interpreter who never wrote songs, said he didn’t think songwriting could be taught.

Thompson: [Laughs] No, I don’t agree with that. Thinking of myself, I’m not good enough to write a symphony, and I’m not good enough to be a really good poet. But I am good enough to do a simpler form of lyric and a simpler form of music, and write songs. The combination of those two skills make you a good songwriter.

I hope it can be taught; otherwise, our camp is a complete waste of time. I don’t think we nail it down where you have to use this rhyme scheme or your subject matter has to be this or that. We have guest songwriters demonstrate their own methods, and that can be inspirational. Sometimes they teach broader points, so it’s up to you as a would-be writer to kind of find your own way. Point you in the right direction, rather than beating you over the head. The other thing we do is listen to attendees’ songs, and without getting too formalized about it say, “Just tweak this a tiny bit, and it’ll be in much better shape.” Somewhere like Nashville, it’s very formulaic: “If you want to be a good Nashville songwriter, this is what you do.” We try not to do that, and keep it looser.

The biggest difference I notice between professional and amateur songwriters is the hook lines. It sounds crude to say, but you can have a fairly abstract song, but if it has a really strong hook that people can remember, it makes a huge difference. The other thing is, if you’re going to write about your life—your pains, your sorrows—make sure it’s interesting for other people. So often people are kind of self-indulgent when they write songs—staring-at-your-shoes kind of songs. Don’t waste people’s time unless you really are finding some interesting commonality between you and the listener.

“I like to meet the muse halfway, in that sense. I don’t wait for lightning to strike.”

Does the guitar side of the retreat encompass all levels of expertise?

Thompson: Absolutely, from beginner to intermediate to advanced. And we teach mostly fingerstyle, to get people beyond just the strum, strum, strum, which is a bit boring. If they know how to strum, adding fingerpicking just gives more possibilities. You can do something more interesting, like a Maybelle Carter thing where you’re picking out the tune in the lower strings. If you can fingerpick, you can play whole melodic things.

You’ve written so many great songs. Have you ever suffered from writer’s block?

Thompson: Every day [laughs]—or every week anyway. Sometimes I’ll go a month without writing, and it’s frustrating. It’s part of the process. You feel frustrated, and then there’s suddenly a sense of release when you write something. To get around that, sometimes I just work on a few things at once. It might be a song I’m desperately trying to finish, but I’ll try other projects as well. If you hit a brick wall as a songwriter, you can stay there for weeks. If you’ve got three songs on the go, then you hit a brick wall and say, “I’ll just sidestep that and work on this other song.” Working on an album, I might have 12 songs in various stages of completion. And I like the fact that I can sit down every day, go through everything, a little bit here, a little bit there, and say, “That one’s finished; don’t need to touch it anymore.” I like to meet the muse halfway, in that sense. I don’t wait for lightning to strike.Richard Thompson 'Money Shuffle' (live acoustic performance)

Thompson’s vibrant, hybrid picking style, smart interpretation of traditional folk songwriting, and powerful vocals are on full display in this live performance of “Money Shuffle” at Goldmark Gallery in Uppingham, England, in 2010.

YouTube Search Term: Richard Thompson ‘Money Shuffle’ (live acoustic performance)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)