We don’t often talk about Renaissance high art and ’50s rock ’n’ roll guitars in the same breath, unless we’re forming a new rockabilly-prog band called Hot-Rod Maximus. (You’re welcome.) But in the modern world of art and guitar collecting, items reputed to be the work of either Leonardo Da Vinci or Leo Fender are subject to much the same scrutiny from experts in the field, are known for fetching vast prices from discriminating buyers, and, given the millions of dollars potentially involved in even a single sale, are likewise expected to stand up to the most rigorous high-tech scientific analysis, as well. Right?

Well, almost. While the worlds of high art, medicine, astronomy, police forensics, and environmentalism have all taken that last cue to heart by making data-driven determinations with the latest tools of chemical analysis, the vintage guitar market—and its many rightfully respected authorities—has generally proven resistant to sharing the process of authentication with the likes of spectrometers, microscopes, and 3D imaging, tools that have long proven their worth in identifying the material composition of everything from planets to polyps to paint thinners. Black lights on the backs of headstocks have typically been about the latest “tech" in the room.

Until now. In a story that feels ripped from The Da Vinci Code or Cold Case Files, two remarkably down-to-earth—if undeniably intrepid—guitar-shop guys from Nashville, Jon Roncolato and Zach Ziemer, have quietly upended the vintage-guitar market in a matter of months. Fueled by rotating batches of fresh-ground coffee, an abundance of nerve, and a stomach for study, they’ve tapped some of the most advanced and expensive analytical machines available to capture, catalog, and compare hundreds of thousands of data points from countless vintage and modern instruments—their lacquers, pigments, pots, pegs, pickups, and parts—building the largest dataset for guitar-component and finish comparison in existence.

In the process, they’ve issued a gentle nudge to dealers, appraisers, and collectors—and yes, they’ve even shifted the status of some long-held vintage “treasures.” Although they no longer appraise or sell instruments themselves, they’ve still managed to ruffle a few feathers and attract more than a few legal threats. At the same time, they’ve leveraged their diligence and strong reputations to assemble a trusted advisory team made up of some of the most respected minds in guitars, art, and hard science: icons like repair guru Joe Glaser, cultural-heritage scientist Dr. Tom Tague (who authenticated Da Vinci’s “lost masterpiece” Salvator Mundi), Music City session legend Tom Bukovac, pickup mastermind Ron Ellis, and analytical chemist Dr. Gene Hall, among others.

Vintage Duco reference/research materials

Jon and Zach are guarded about the technology, as you might expect. They don’t post selfies, they don’t have a podcast, and they won’t be starting one. As Ziemer puts it, they’d much rather “keep our heads down and keep hammering away” with laser-based spectrometers, plumb the deepest secrets of Fullerton red Strats, and compare the chemical makeup of Duco paints (ironically, both Pollock and Fender’s mutual go-to.) In their scrupulously clean Nashville HQ—which will expand to offices in L.A. and N.Y.C. in 2026—they seem pretty resigned to their current controversial status, and remain motivated primarily by going after, y'know, the truth.

Okay, that and a good cup of coffee.

What was the genesis of this idea to apply these types of cultural heritage sciences to vintage guitars? Is the problem with inaccuracies, refinishes, and forgeries really that widespread?

Jon Roncolato: We met while I was the GM at Carter Vintage Guitars in Nashville. We initially hired Zach as part of the inspection team. It’s difficult to find people who have logged enough time examining vintage instruments to truly know what they’re looking at, but Zach had spent a couple years at Glaser Instruments—the go-to shop for repairs on high-dollar pieces.

When Zach became Head of Authentication, we began seeing questionable instruments come through with six-figure price tags that other experts had already signed off on. When you have a six-figure instrument and multiple experts all saying different things, you’ve got a problem. That’s when we realized there had to be a better way to do this—something grounded in science, not speculation.

Zach Ziemer: Everybody misses now and again. Most dealers are trying their absolute hardest with their experience, eye, and gut to tell an original from a fake or a refin. There’s simply some things you just can’t know unless you look at them with the kinds of tools that we’re bringing to the table. And it shouldn’t be that controversial: after all, literally every other collectible industry has a third party unassociated service like ours. The most obvious one is PSA with collectible sports cards. PSA is a little different than it used to be, but everybody still sees a sports card and a PSA box and if it says, “PSA 9,” for instance, you know you’re probably in good shape.

“In the art world, scientific validation has long been standard practice—pigment analysis, canvas fiber studies, dimensional scans. Sometimes it changes the story. That’s not an attack on tradition. It’s the pursuit of truth.” —George Gruhn, Gruhn Guitars

Vintage Verified Individual Component analysis box.

Jon Roncolato: In the art world, if you don’t have both iron-clad provenance and scientific analysis, it’s not possible to certify a piece as unequivocally “by the hand” of a given artist. Art dealers are very specific about their language, and there’s a whole hierarchy of degrees of certainty that directly correlate to the price of the piece. In the world of dealing guitars, though, even if you’re not 100% sure, you have to absolutely stake all your credibility on a guitar, even if there’s some doubt. You're not going to sell a $250,000 custom color Fender if you come out and say, “Well, I think it's a custom color. It looks good to me.” So that's just been the structure of the industry. Being in the underbelly of the whole thing, as we were, we realized what a big problem this was.

There must have been a ridiculous learning curve. You guys are guitar dudes, not scientists. Takes a bit of brass to bite off something like that, no?

Jon Roncolato: We have a framed quote in the kitchen from Wilbur Wright: "There are two ways of learning to ride a fractious horse: one is to get on him and learn by actual practice how each motion and trick may be best met. The other is to sit on a fence and watch the beast awhile, and then retire to the house." We chose the former.

That said, we spent the first year and a half offering no services at all—just studying the science. That included week-long training seminars where everyone but us had a doctorate attached to their name, and consulting with the top experts in the cultural heritage field.

We also didn’t get here alone. We caught a major break by connecting with Dr. Tom Tague and Dr. Gene Hall, two of the world’s leading experts in analytical chemistry. They took us under their wing and gave us a crash course in PhD-level material analysis.

Zach Ziemer: I can't even express how difficult it was to make heads or tails of any of this at first. Jon and I were not chemists, and a lot of what we do now is largely analytical chemistry. So the learning curve on that was incredibly steep. We always joked that we were smart enough to have the idea, but dumb enough to think we could do it. And while this process exists in other industries, the finished instrument industry is totally unique. The instruments are so modular, and you have finishes, plastics, hardware, pickups, and so you have to have an answer for all that information.

Jon Roncolato: That’s right. The process is designed to have an answer for anything and everything on the instrument. The headstock decals, the finish, the hardware, the fret wire, the fingerboard inlays—we have a data-driven answer for everything. That was really critical, because we didn't want to give incomplete information. Another absolutely critical principle for us was that anything we put in one of these reports has to be defensible in court. If we get subpoenaed to go to court, which inevitably we will, we need to know that Zach or I can show up and we can defend this and prove this. Our other guiding principle is that we remain completely independent, and not touch the buying and selling of the instruments.

“Vintage Verified is doing what we couldn’t do 20 years ago. They’re bringing in real tools—from forensics, from art conversation, from aerospace—and applying them to guitars. And it’s not about replacing experience. It’s about supporting it.” —Joe Glaser, Glaser Guitars

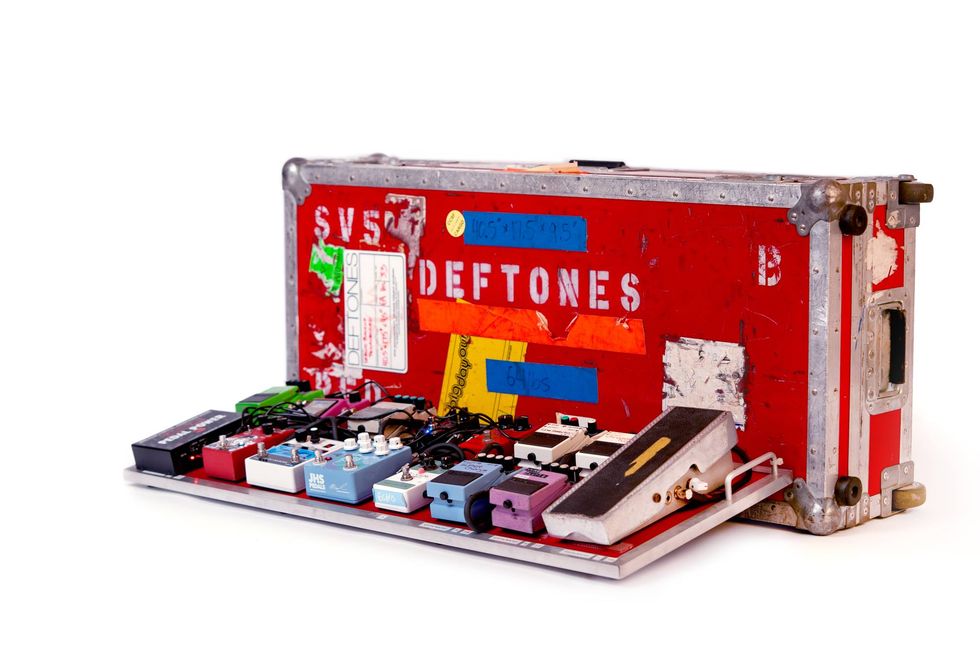

The workshop

Fair enough. So, what’s the most difficult or highly sensitive area of your analysis?

Jon Roncolato: Finish is easily the most complicated part of what we do, an absolute maze of information, and it’s also where you see the biggest value swings. Traditionally, if a guitar’s been refinished, the rule of thumb is that it cuts the value in half. Nowadays, it probably cuts the value by 40%. But if you start talking about custom colors, like a Fender Sonic Blue Strat, or the Fullerton red we have in our lab right now, this Strat here is probably a $250,000 Strat, assuming the finish is original. If the finish is, in fact, not legitimate, then potentially you’re looking at a $20,000 Strat.

And to determine this, you don’t just need that guitar’s own fingerprint, if you will, but you need to be able to conduct comparative analysis against a bulwark of trustworthy data. Where does that come from?

Jon Roncolato: We’ve been very fortunate to have guys like Joe Glaser and George Gruhn in our corner, who put their own cred on the line to help us scan and analyze literally thousands of vintage guitars, plus Dr. Gene Hall, whose work decoding Jackson Pollock paintings means he has the largest collection and database of period-correct Duco, Ditzler, R-M, Sherwin Williams, etc. paints on the planet, the same paints Fender used in their golden era. That’s just the tip of the iceberg. We now have millions of data points across several different machines, a good $500,000 worth of spectrometers alone. We spent eight hours a day, all day, every day, collecting data as much as we possibly could.

So is it very much a one-to-one comparison? “This finish’s chemical composition is true to the year this guitar purports to be, so we’re good”? Or is it more complex than that?

Zach Ziemer: A little of both. Sure, the data that I just grabbed matches the aggregate of the given model/era pretty well, so therefore we can say with a high degree of certainty that it’s a period-correct material. But what really blew the doors open for us was when we got past that level, and started to have a fundamental understanding of these lacquer formulations, how various formulations over time were degrading, and how the different components in a lacquer formulation—plasticizers, pigments, etc.—all interact and evolve. How did those components morph over time?

If the government set regulations, what was the regulation attached to? If you look at a spectrum of a given lacquer, you’ll have hundreds of chemical compounds. A ton of information in there. What we had to do was figure out which chemical compounds were going to be chief identifiers of who was using what, and when. Building out this timeline for the major manufacturers was the bulk of our work, just as much as developing an understanding of the complexity of the materials. In other words, the data is only valuable if you understand the materials that are producing the data.

You’ve encountered some backlash, and even dealers who later became supporters initially had their lawyers on the phone. What’s your message to dealers, appraisers, collectors, working players, and the business as a whole?

Jon Roncolato: We knew there would be a significant amount of skepticism and backlash early on, just as there always is around a new service or technology. It’s like the wagon wheel salesman in the age of the automobile. Zach and I think they’ll come around eventually. One positive aspect of our service is that it allows buyers who would otherwise not feel comfortable spending large amounts of money on a piece to now buy with confidence. For years, many people at the top of the market wouldn’t buy custom color Fenders, wouldn’t buy Flying Vs. Because they were largely under the impression that many of them are refins or counterfeit pieces. So, already we’ve seen that many of these people who previously were not buying custom colors, bursts, or whatever, are now joining that market again because they have the trust that these are authentic.

Zach Ziemer: Our mission is to make sure that the data and the information we provide is absolutely correct. That’s our lane. We're not the guitar police. We are not policing transactions, and we do not appraise or assign any type of valuation, monetary or otherwise, to any instrument, ever. We’re hoping that we can help dealers begin to understand that this is designed to be an asset. It’s designed to help you protect yourself. And look, as soon as we print out a report, and I hand it to you, you can throw it in the garbage if you want. But it’s an option for you. Ultimately, it’s something that we believe helps give people the confidence to buy and sell high-value instruments, and know exactly what they’re getting.