There’s a downside to being a legend.

Myths, rumors, tall tales, and allegations

swirl around you and obscure the

truth like mists around some magical isle in

a fantasy novel. Legend distorts reality.

Such is the case with Hank Garland and his place in the annals of guitar history. To those in the know, his story is fraught with innuendo, hearsay, and familial strife. But, brush that aside, and the truth emerges— and it’s a truth all guitarists can agree upon: Garland was an incredible player.

The Early Years

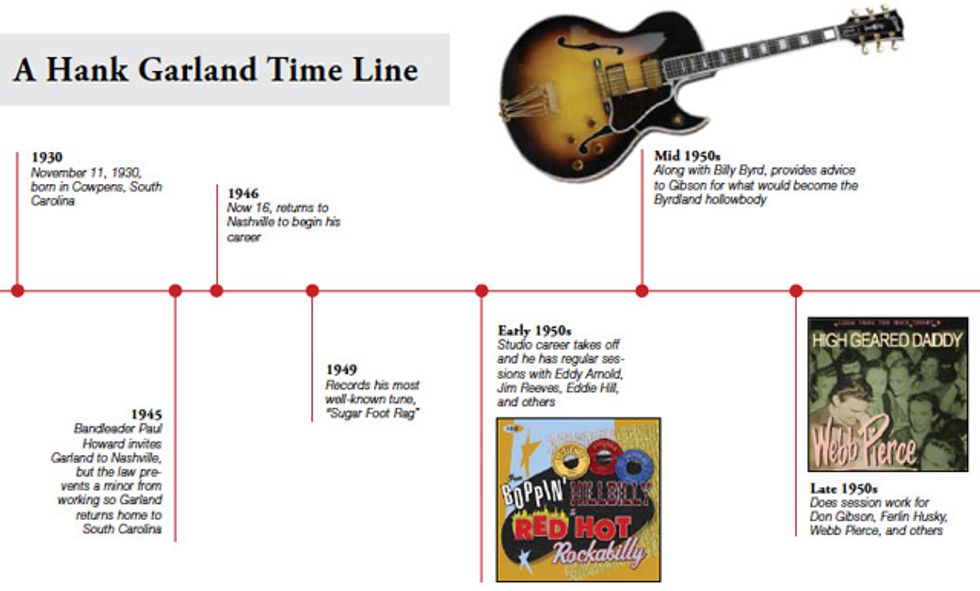

Walter Louis “Hank” Garland (November 11, 1930–December 27, 2004) was born in Cowpens, South Carolina—a town that, even today, has only slightly more than 2,000 residents. During Garland’s childhood, most of the locals were listening to country music, and he was no different. One of his biggest musical influences was seminal folk group the Carter Family.

According to the Garland family’s website dedicated to Hank, his first guitar was a four-dollar Encore steel-string that his father purchased for him. A neighbor provided the budding musician with lessons to augment his own attempts to copy tunes from the radio. At 14, he impressed Paul Howard of the Arkansas Cotton Pickers, who subsequently took the young guitarist to Nashville. Garland eventually appeared on the Grand Ole Opry. During this initial foray into country music’s heartland, Garland met guitarists Harold Bradley and Billy Byrd. They felt the young player was obviously talented, but still a bit rough. His age became a more pressing concern when authorities realized he was too young to work regularly. Garland was forced to return to South Carolina.

When he was of legal age, he came back to Music City and reconnected with Byrd and Bradley. “Billy and I were his mentors,” Bradley remembers. “But he immediately left us in the dust—he was so talented.” That’s high praise coming from someone like Bradley, who was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2006 and who received a Trustee Award at the 2010 Grammy Awards ceremony.

Back on the Scene and Going Big

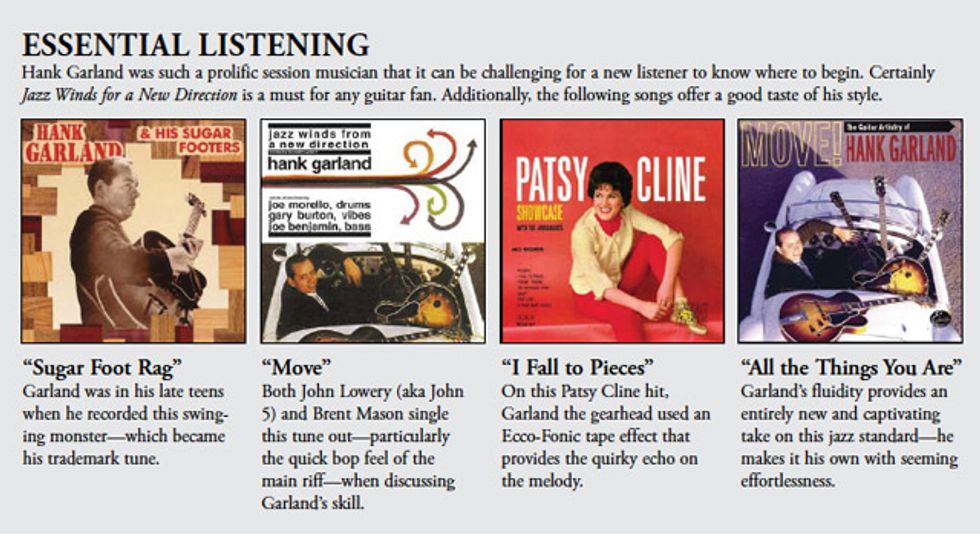

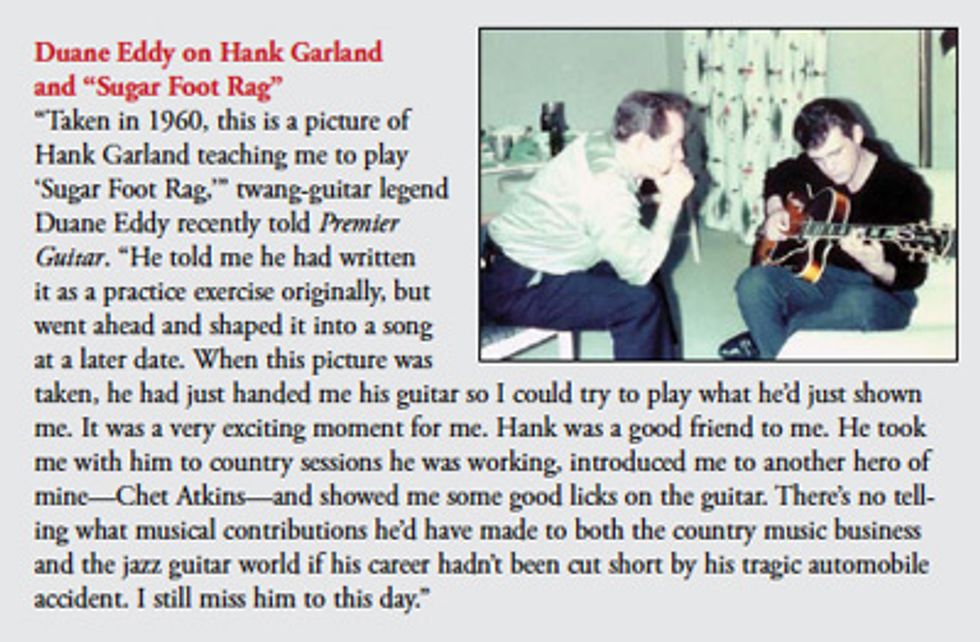

According to Bradley, Garland initially found it difficult to get session work in Nashville, but he eventually broke through and became one of the most in-demand pickers on the scene. His “Sugar Foot Rag”—a guitar-heavy single available in two versions, one with Red Foley on vocals and an instrumental rendition that put Garland’s fleet fingers center stage—became a huge hit, with more than a million copies sold.

The skill Garland demonstrated in “Sugar Foot Rag” continues to inspire guitar players of every stripe to this day. Venerated session ace Brent Mason—whose schedule is as jam-packed as any musician’s in Nashville today—is among the legions of players who have paid homage to the song (on his 1997 release Hot Wired).

“I admired his capacity to play what’s in his heart in his music,” Mason says, “and then, on the other side of it, go in and be a session player and be commercial—to have both of those worlds. You don’t see a lot of guys who can jump in one genre and then into another. It’s tough for a jazz guitarist to stay on the same lines as a piano and saxophone—sometimes jazz licks don’t play that great on guitar. But Hank was one of the few who could do it. He had a real smoothness and very melodic lines. Everything was real fluid, and his technique was tremendously stellar. Whatever the style, I never could find a weakness in his work.”

Even metal shredder John Lowery (aka John 5) cites Garland as the first axe man to really strike a chord with him. “‘Sugar Foot Rag’ is on my first instrumental record because I felt like I grew up with Hank. He was the guitar hero, the shredder back in the day,” Lowery says. “He was the man. I guarantee that if kids today would check him out, his popularity would skyrocket. There are so many great recordings people should listen to. It will blow their minds.”

“Sugar Foot Rag” was the only “hit” to officially bear Garland’s name, but he contributed to a host of popular singles for other performers. His days were devoted to quick, efficient sessions in Nashville studios, while his evenings were spent in smoky bars in Printer’s Alley—places like the Carousel Club, where audiences were required to be silent and waiters strolled the room in red coats. It was in the latter environment that Garland indulged in a different genre—jazz. Owing to his time in these contrasting worlds, Garland developed an incredible ability to seamlessly shift between styles in a manner that would become one of his hallmarks.

Gear Preferences

In the mid ’50s, Garland influenced guitar manufacturing when he and Billy Byrd helped design what would eventually become the Gibson Byrdland hollowbody. Some of the specifics Garland and Byrd requested included a thinner body and a 23.5" scale. The company kept the first Byrdland off the line, and Garland got the second instrument.

Garland also experimented with different instruments and effects on his recordings. For example, he employed an Ecco-Fonic tape echo on Patsy Cline’s smash “I Fall to Pieces.”

Despite Garland’s association with Gibson, he felt no compunction about using other gear to get the right sound. “He borrowed my Strat to play on ‘Little Sister’ with Elvis,” Bradley says. “He told me, ‘Yours twangs more than mine,’ because he was playing a Gibson.”

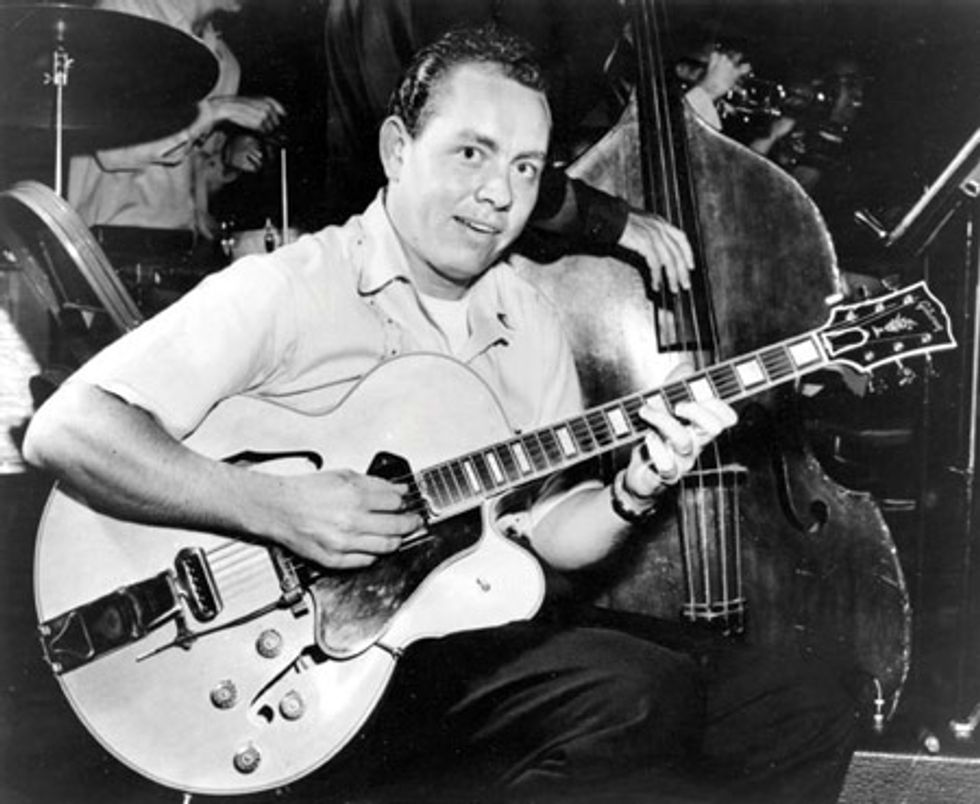

In this 1950s press photo, Garland plays a gig with a circa-1956 Gibson Byrdland hollowbody.

Prelude to Tragedy

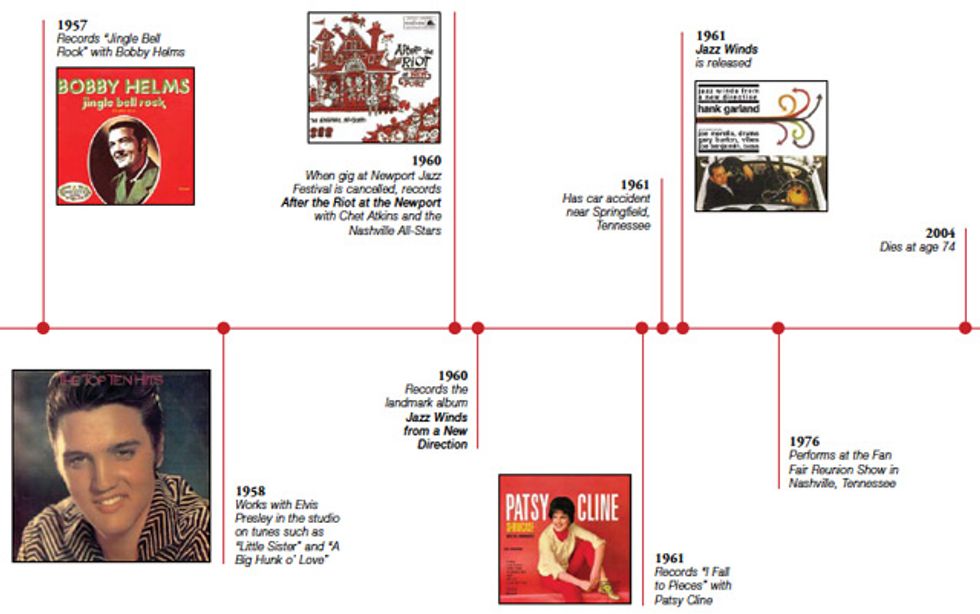

In addition to Elvis Presley and Patsy Cline, Garland worked with such seminal artists as Jim Reeves, Roy Orbison, and Conway Twitty. He even performed on one of the holiday season’s most timeless tunes. “He and I played the intro to ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ by Bobby Helms,” Bradley says. “He’s playing the lead and I’m playing the harmony.”

In 1961, Garland released Jazz Winds from

a New Direction, a groundbreaking record that

featured Joe Benjamin on bass, Joe Morello

on drums, and a young vibraphone player

named Gary Burton. The vibraphone legend

remembers that Garland had a “fluid, facile

technical command of the guitar,” and that

he took routes and directions usually reserved

for musicians playing other instruments. “The

recording sessions featured Hank at his best.

Being a studio musician, he was very comfortable

in a studio setting. But, in this case, it

was new musicians and new music, in a genre

that was still relatively new to Hank. But he

was confident and cool and knew just how to

bond with the musicians on the session.”

In 1961, Garland released Jazz Winds from

a New Direction, a groundbreaking record that

featured Joe Benjamin on bass, Joe Morello

on drums, and a young vibraphone player

named Gary Burton. The vibraphone legend

remembers that Garland had a “fluid, facile

technical command of the guitar,” and that

he took routes and directions usually reserved

for musicians playing other instruments. “The

recording sessions featured Hank at his best.

Being a studio musician, he was very comfortable

in a studio setting. But, in this case, it

was new musicians and new music, in a genre

that was still relatively new to Hank. But he

was confident and cool and knew just how to

bond with the musicians on the session.”

Jazz Winds blew away Nashville’s country music establishment. But Garland seemed to do that on a regular basis—at least according to legend. The 2007 movie Crazy (which was co-produced by Steve Vai and features cameos from him and Tony MacAlpine) depicts Garland as a player who bristled at the regimented and closed-minded nature of Nashville’s music industry. But critics say Crazy is more fabrication than truth (which may be why the opening credits begin with “Inspired by a legend” rather than “Based on a true story”).

Although it’s unclear whether it began with some sort of familial strife, as depicted in Crazy, in September 1961 Garland was apparently under the impression that his wife, Evelyn, had left town with their daughters and was headed to Milwaukee to visit family. The guitarist hit the highway in pursuit and was involved in a near-fatal car accident near Springfield, Tennessee.

Some members of his family have said in online forums that the musician hit an embankment and lost control. Others allege that his car was forced off the road by music-industry goons determined to prove a point. But Bradley dismisses all the conjecture. “[It’s] all trash—it’s all wrong.” He emphatically states that there were never any rumors of malfeasance at the time of the accident.

While the veracity of the more dramatic theories may never be known, there’s no doubt that the car crash marked the decline of Garland’s career. Depending on who you ask, he suffered brain damage from either the car crash or subsequent shock-therapy treatments at Madison Sanitarium. And that’s just the tip of the tragic iceberg. Allegations of depression and infidelity abound about this period in Garland’s life. Whatever the case, he left Nashville and stayed with family for a time before eventually settling in Orange Park, Florida.

As a testament to the esteem that Nashville musicians held for Garland, they funneled money to his family for years. At the time, session players were required to sign documents when they completed work in order to get paid. Rumor has it that Garland’s name was often written in by generous colleagues.

“I know it’s true, because I signed some of them,” Bradley says. “I remember one time looking into the book and seeing that Garland signed into a session that occurred more than a year after the accident.”

Garland spent years learning to play again, but he never fully regained his former level of mastery. He performed in public rarely over the decades, most notably appearing at a 1976 fan appreciation show in Nashville. In a 1981 Guitar Player interview, Garland said, “I’m going to take what the Lord left me with and do better things with it, if I can.”

An Undeniable Legacy

Today, Garland family members duke it out

on various websites and forums, arguing

about who cared for Garland the most, who

has the most accurate version of the story,

and so forth. It’s a sad situation for any

family. So perhaps the best way to gauge the

reality of Garland’s impact is through the

perspectives of the musicians he influenced.

“He’s one of the most talented musicians I have encountered in my career,” says Burton. “His obvious enthusiasm for whatever music he was playing was inspiring to everyone around him. I’ve always thought that was one of the reasons he was so popular in Nashville and why everyone wanted Hank to be on their sessions. His very presence seemed to create a buzz among the musicians, whether it was country, rock, or jazz.”

Bradley recalls that it wasn’t just Garland’s skill that put him in such high demand—it was also his personal warmth. “He was an exceptional guitar player. We have people who play fast now, but we don’t have anyone who plays the lines he played. They’re very schooled, but they don’t have the swing and the tone and the feel that Hank had. He was one of a kind. He was miles ahead of us, and we’ll never catch him. But all the guitar stuff aside, he was just a great, great friend.”

Ultimately, the varying recollections and legends regarding Hank Garland dissipate like mist in the morning sun. Because the reality of his musical legacy is indisputable: It’s on records, on tape. It’s in yellowing session pages decaying in Nashville office buildings. Ignore the controversy, the allegations, and just lose track of time while listening to songs like “Sugar Foot Rag” or “Move.” In those melodies, the speedy licks, the warm tone, you’ll find the true measure of Hank Garland.

Special thanks to Bear Family Records for their assistance with this story.

Hallmarks of Garland's Style

By Jason Shadrick

Even though Hank Garland made his name by playing on classic country sessions, he was a jazz musician through and through. Released in 1961, his breakthrough album Jazz Winds from a New Direction featured some of the best young jazz talent around. This recording showed off Garland’s formidable jazz chops, his ability to arrange jazz standards into something new, and his indelible sense of swing.

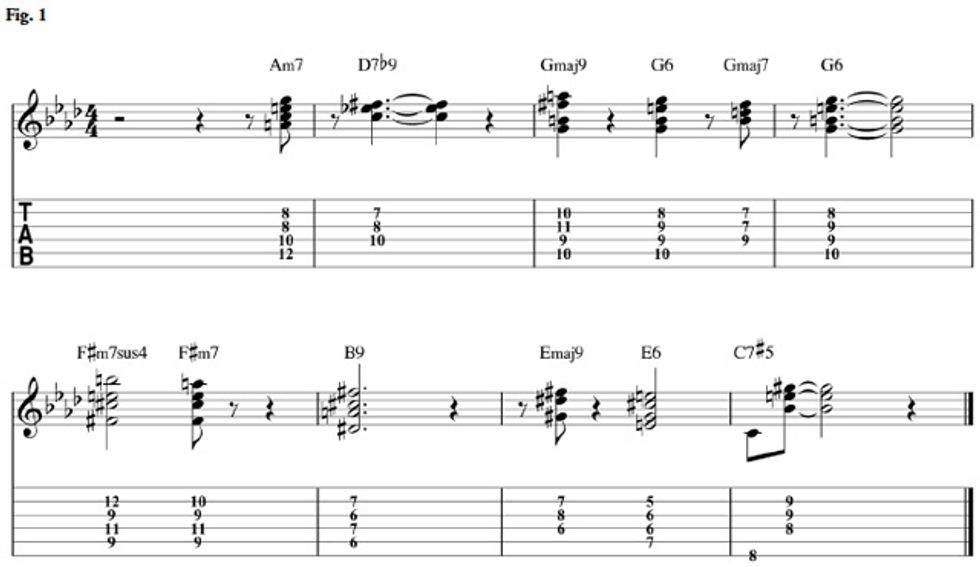

In Fig. 1, you can see a passage similar to what Garland played on the changes to the bridge of “All the Things You Are.” While a 17-year-old Gary Burton played the melody on vibes, Garland comes in with a swinging eight-measure passage that combines drop-2 chords, clusters, and triads. The bridge’s harmony is classic jazz-standard material with the first four measures outlining a ii–V–I progression in G major, and the second four measures moving that progression to the key of E major.

Typical of jazz harmony, the chords are extended with such alterations as the D7b9 cluster played in the second measure. Here, Garland took the chord’s most essential notes (the 3 and b7) and then added the b9 in the middle of the voicing. The rub between the Eb and F# creates a tension-filled voicing that connects nicely with the root-position Am7 in the previous measure. Notice how the C is carried over, while the top two notes of Am7 (G and E) descend by a half-step to F# and Eb. This is a textbook example of voice-leading in a jazz context.

In the third measure, there is a descending melodic motif that connects all the chords. It begins with the A at the top of the Gmaj9 chord and connects diatonically through the G6 chord in the fourth measure. At the end of the third measure, Garland plays a root-position Bm triad to illustrate the G major tonality. Since Bm is the relative minor of G, all the notes in the triad are diatonic and work to give the chord that Gmaj7 sound. Next time you see a vamp in G, try playing Bm triads all around the neck. It will sound hip and open up the fretboard to some new comping ideas.

Basing chords off of guide tones is a technique used extensively by Barney Kessel and Barry Galbraith, two big influences on Garland. In measure six, Garland voices a B9 chord by starting with the 3 and b7, and then stacking the root and 9 on top. Since the bass player is covering the root, in this case B, you can leave it out and still keep the harmonic integrity intact. The Emaj9 in the next measure and the final C7#5 both use guide tones as a foundation for the chord voicings.

Garland’s single-note improvisations combined a bebop vocabulary with a driving rhythmic intensity that reminds me of early Tal Farlow recordings. The example shown in Fig. 2 is quintessential Garland—a long, flowing stream of eighth-notes combined with interesting note choices and reckless abandon. The example begins with a descending scalar line that goes through F Dorian (F–G–Ab–Bb–C–Db–Eb) and lands on Fm7’s 9 (G) on the downbeat. There are times where Garland seems to hit “wrong” notes, but considering the tempo and the strength of his sense of swing, they go by without too much hassle. For instance, in the second measure of this example, he lands on a D natural that clashes with Bbm7’s b3 (Db).

Bebop sensibilities come into play in the third measure over the Eb7 chord when Garland descends chromatically from the root (on beat 1) down to the %7 and then skips to the #5. He gets a lot of mileage out of hitting the extensions (#5, 11, and 9) before moving onto the 11 on the Abmaj7 chord in the next measure. Finally, Garland ends the phrase with some textbook voice-leading, moving from the b7 (Gb) against the Abmaj7 to the 3 of the Dbmaj7 (F). Approaching a chord tone by a half-step—especially at points in the harmonic rhythm where the chord changes—is a common technique that makes single-note lines flow more easily.

At his heart, Hank Garland was a jazz guitarist of the highest caliber. Few guitarists of his generation were able to successfully live in the two (seemingly) unrelated worlds of country music sessions and after-hours jazz clubs. A great document of Hank’s jazz chops is Move! The Guitar Artistry of Hank Garland that covers all of his Columbia Records sessions in 1959 and 1960. Included is the entire Jazz Winds album in addition to Velvet Guitar and The Unforgettable Guitar of Hank Garland.

Search YouTube for “Hank Garland - Sugarfoot Rag” to see Garland playing his signature tune.

Such is the case with Hank Garland and his place in the annals of guitar history. To those in the know, his story is fraught with innuendo, hearsay, and familial strife. But, brush that aside, and the truth emerges— and it’s a truth all guitarists can agree upon: Garland was an incredible player.

The Early Years

Walter Louis “Hank” Garland (November 11, 1930–December 27, 2004) was born in Cowpens, South Carolina—a town that, even today, has only slightly more than 2,000 residents. During Garland’s childhood, most of the locals were listening to country music, and he was no different. One of his biggest musical influences was seminal folk group the Carter Family.

According to the Garland family’s website dedicated to Hank, his first guitar was a four-dollar Encore steel-string that his father purchased for him. A neighbor provided the budding musician with lessons to augment his own attempts to copy tunes from the radio. At 14, he impressed Paul Howard of the Arkansas Cotton Pickers, who subsequently took the young guitarist to Nashville. Garland eventually appeared on the Grand Ole Opry. During this initial foray into country music’s heartland, Garland met guitarists Harold Bradley and Billy Byrd. They felt the young player was obviously talented, but still a bit rough. His age became a more pressing concern when authorities realized he was too young to work regularly. Garland was forced to return to South Carolina.

When he was of legal age, he came back to Music City and reconnected with Byrd and Bradley. “Billy and I were his mentors,” Bradley remembers. “But he immediately left us in the dust—he was so talented.” That’s high praise coming from someone like Bradley, who was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2006 and who received a Trustee Award at the 2010 Grammy Awards ceremony.

Back on the Scene and Going Big

According to Bradley, Garland initially found it difficult to get session work in Nashville, but he eventually broke through and became one of the most in-demand pickers on the scene. His “Sugar Foot Rag”—a guitar-heavy single available in two versions, one with Red Foley on vocals and an instrumental rendition that put Garland’s fleet fingers center stage—became a huge hit, with more than a million copies sold.

The skill Garland demonstrated in “Sugar Foot Rag” continues to inspire guitar players of every stripe to this day. Venerated session ace Brent Mason—whose schedule is as jam-packed as any musician’s in Nashville today—is among the legions of players who have paid homage to the song (on his 1997 release Hot Wired).

“I admired his capacity to play what’s in his heart in his music,” Mason says, “and then, on the other side of it, go in and be a session player and be commercial—to have both of those worlds. You don’t see a lot of guys who can jump in one genre and then into another. It’s tough for a jazz guitarist to stay on the same lines as a piano and saxophone—sometimes jazz licks don’t play that great on guitar. But Hank was one of the few who could do it. He had a real smoothness and very melodic lines. Everything was real fluid, and his technique was tremendously stellar. Whatever the style, I never could find a weakness in his work.”

Even metal shredder John Lowery (aka John 5) cites Garland as the first axe man to really strike a chord with him. “‘Sugar Foot Rag’ is on my first instrumental record because I felt like I grew up with Hank. He was the guitar hero, the shredder back in the day,” Lowery says. “He was the man. I guarantee that if kids today would check him out, his popularity would skyrocket. There are so many great recordings people should listen to. It will blow their minds.”

“Sugar Foot Rag” was the only “hit” to officially bear Garland’s name, but he contributed to a host of popular singles for other performers. His days were devoted to quick, efficient sessions in Nashville studios, while his evenings were spent in smoky bars in Printer’s Alley—places like the Carousel Club, where audiences were required to be silent and waiters strolled the room in red coats. It was in the latter environment that Garland indulged in a different genre—jazz. Owing to his time in these contrasting worlds, Garland developed an incredible ability to seamlessly shift between styles in a manner that would become one of his hallmarks.

Gear Preferences

In the mid ’50s, Garland influenced guitar manufacturing when he and Billy Byrd helped design what would eventually become the Gibson Byrdland hollowbody. Some of the specifics Garland and Byrd requested included a thinner body and a 23.5" scale. The company kept the first Byrdland off the line, and Garland got the second instrument.

Garland also experimented with different instruments and effects on his recordings. For example, he employed an Ecco-Fonic tape echo on Patsy Cline’s smash “I Fall to Pieces.”

Despite Garland’s association with Gibson, he felt no compunction about using other gear to get the right sound. “He borrowed my Strat to play on ‘Little Sister’ with Elvis,” Bradley says. “He told me, ‘Yours twangs more than mine,’ because he was playing a Gibson.”

In this 1950s press photo, Garland plays a gig with a circa-1956 Gibson Byrdland hollowbody.

Prelude to Tragedy

In addition to Elvis Presley and Patsy Cline, Garland worked with such seminal artists as Jim Reeves, Roy Orbison, and Conway Twitty. He even performed on one of the holiday season’s most timeless tunes. “He and I played the intro to ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ by Bobby Helms,” Bradley says. “He’s playing the lead and I’m playing the harmony.”

In 1961, Garland released Jazz Winds from

a New Direction, a groundbreaking record that

featured Joe Benjamin on bass, Joe Morello

on drums, and a young vibraphone player

named Gary Burton. The vibraphone legend

remembers that Garland had a “fluid, facile

technical command of the guitar,” and that

he took routes and directions usually reserved

for musicians playing other instruments. “The

recording sessions featured Hank at his best.

Being a studio musician, he was very comfortable

in a studio setting. But, in this case, it

was new musicians and new music, in a genre

that was still relatively new to Hank. But he

was confident and cool and knew just how to

bond with the musicians on the session.”

In 1961, Garland released Jazz Winds from

a New Direction, a groundbreaking record that

featured Joe Benjamin on bass, Joe Morello

on drums, and a young vibraphone player

named Gary Burton. The vibraphone legend

remembers that Garland had a “fluid, facile

technical command of the guitar,” and that

he took routes and directions usually reserved

for musicians playing other instruments. “The

recording sessions featured Hank at his best.

Being a studio musician, he was very comfortable

in a studio setting. But, in this case, it

was new musicians and new music, in a genre

that was still relatively new to Hank. But he

was confident and cool and knew just how to

bond with the musicians on the session.”Jazz Winds blew away Nashville’s country music establishment. But Garland seemed to do that on a regular basis—at least according to legend. The 2007 movie Crazy (which was co-produced by Steve Vai and features cameos from him and Tony MacAlpine) depicts Garland as a player who bristled at the regimented and closed-minded nature of Nashville’s music industry. But critics say Crazy is more fabrication than truth (which may be why the opening credits begin with “Inspired by a legend” rather than “Based on a true story”).

Although it’s unclear whether it began with some sort of familial strife, as depicted in Crazy, in September 1961 Garland was apparently under the impression that his wife, Evelyn, had left town with their daughters and was headed to Milwaukee to visit family. The guitarist hit the highway in pursuit and was involved in a near-fatal car accident near Springfield, Tennessee.

Some members of his family have said in online forums that the musician hit an embankment and lost control. Others allege that his car was forced off the road by music-industry goons determined to prove a point. But Bradley dismisses all the conjecture. “[It’s] all trash—it’s all wrong.” He emphatically states that there were never any rumors of malfeasance at the time of the accident.

While the veracity of the more dramatic theories may never be known, there’s no doubt that the car crash marked the decline of Garland’s career. Depending on who you ask, he suffered brain damage from either the car crash or subsequent shock-therapy treatments at Madison Sanitarium. And that’s just the tip of the tragic iceberg. Allegations of depression and infidelity abound about this period in Garland’s life. Whatever the case, he left Nashville and stayed with family for a time before eventually settling in Orange Park, Florida.

As a testament to the esteem that Nashville musicians held for Garland, they funneled money to his family for years. At the time, session players were required to sign documents when they completed work in order to get paid. Rumor has it that Garland’s name was often written in by generous colleagues.

“I know it’s true, because I signed some of them,” Bradley says. “I remember one time looking into the book and seeing that Garland signed into a session that occurred more than a year after the accident.”

Garland spent years learning to play again, but he never fully regained his former level of mastery. He performed in public rarely over the decades, most notably appearing at a 1976 fan appreciation show in Nashville. In a 1981 Guitar Player interview, Garland said, “I’m going to take what the Lord left me with and do better things with it, if I can.”

An Undeniable Legacy

|

“He’s one of the most talented musicians I have encountered in my career,” says Burton. “His obvious enthusiasm for whatever music he was playing was inspiring to everyone around him. I’ve always thought that was one of the reasons he was so popular in Nashville and why everyone wanted Hank to be on their sessions. His very presence seemed to create a buzz among the musicians, whether it was country, rock, or jazz.”

Bradley recalls that it wasn’t just Garland’s skill that put him in such high demand—it was also his personal warmth. “He was an exceptional guitar player. We have people who play fast now, but we don’t have anyone who plays the lines he played. They’re very schooled, but they don’t have the swing and the tone and the feel that Hank had. He was one of a kind. He was miles ahead of us, and we’ll never catch him. But all the guitar stuff aside, he was just a great, great friend.”

Ultimately, the varying recollections and legends regarding Hank Garland dissipate like mist in the morning sun. Because the reality of his musical legacy is indisputable: It’s on records, on tape. It’s in yellowing session pages decaying in Nashville office buildings. Ignore the controversy, the allegations, and just lose track of time while listening to songs like “Sugar Foot Rag” or “Move.” In those melodies, the speedy licks, the warm tone, you’ll find the true measure of Hank Garland.

Special thanks to Bear Family Records for their assistance with this story.

Hallmarks of Garland's Style

By Jason Shadrick

Even though Hank Garland made his name by playing on classic country sessions, he was a jazz musician through and through. Released in 1961, his breakthrough album Jazz Winds from a New Direction featured some of the best young jazz talent around. This recording showed off Garland’s formidable jazz chops, his ability to arrange jazz standards into something new, and his indelible sense of swing.

In Fig. 1, you can see a passage similar to what Garland played on the changes to the bridge of “All the Things You Are.” While a 17-year-old Gary Burton played the melody on vibes, Garland comes in with a swinging eight-measure passage that combines drop-2 chords, clusters, and triads. The bridge’s harmony is classic jazz-standard material with the first four measures outlining a ii–V–I progression in G major, and the second four measures moving that progression to the key of E major.

Typical of jazz harmony, the chords are extended with such alterations as the D7b9 cluster played in the second measure. Here, Garland took the chord’s most essential notes (the 3 and b7) and then added the b9 in the middle of the voicing. The rub between the Eb and F# creates a tension-filled voicing that connects nicely with the root-position Am7 in the previous measure. Notice how the C is carried over, while the top two notes of Am7 (G and E) descend by a half-step to F# and Eb. This is a textbook example of voice-leading in a jazz context.

In the third measure, there is a descending melodic motif that connects all the chords. It begins with the A at the top of the Gmaj9 chord and connects diatonically through the G6 chord in the fourth measure. At the end of the third measure, Garland plays a root-position Bm triad to illustrate the G major tonality. Since Bm is the relative minor of G, all the notes in the triad are diatonic and work to give the chord that Gmaj7 sound. Next time you see a vamp in G, try playing Bm triads all around the neck. It will sound hip and open up the fretboard to some new comping ideas.

Basing chords off of guide tones is a technique used extensively by Barney Kessel and Barry Galbraith, two big influences on Garland. In measure six, Garland voices a B9 chord by starting with the 3 and b7, and then stacking the root and 9 on top. Since the bass player is covering the root, in this case B, you can leave it out and still keep the harmonic integrity intact. The Emaj9 in the next measure and the final C7#5 both use guide tones as a foundation for the chord voicings.

Garland’s single-note improvisations combined a bebop vocabulary with a driving rhythmic intensity that reminds me of early Tal Farlow recordings. The example shown in Fig. 2 is quintessential Garland—a long, flowing stream of eighth-notes combined with interesting note choices and reckless abandon. The example begins with a descending scalar line that goes through F Dorian (F–G–Ab–Bb–C–Db–Eb) and lands on Fm7’s 9 (G) on the downbeat. There are times where Garland seems to hit “wrong” notes, but considering the tempo and the strength of his sense of swing, they go by without too much hassle. For instance, in the second measure of this example, he lands on a D natural that clashes with Bbm7’s b3 (Db).

Bebop sensibilities come into play in the third measure over the Eb7 chord when Garland descends chromatically from the root (on beat 1) down to the %7 and then skips to the #5. He gets a lot of mileage out of hitting the extensions (#5, 11, and 9) before moving onto the 11 on the Abmaj7 chord in the next measure. Finally, Garland ends the phrase with some textbook voice-leading, moving from the b7 (Gb) against the Abmaj7 to the 3 of the Dbmaj7 (F). Approaching a chord tone by a half-step—especially at points in the harmonic rhythm where the chord changes—is a common technique that makes single-note lines flow more easily.

At his heart, Hank Garland was a jazz guitarist of the highest caliber. Few guitarists of his generation were able to successfully live in the two (seemingly) unrelated worlds of country music sessions and after-hours jazz clubs. A great document of Hank’s jazz chops is Move! The Guitar Artistry of Hank Garland that covers all of his Columbia Records sessions in 1959 and 1960. Included is the entire Jazz Winds album in addition to Velvet Guitar and The Unforgettable Guitar of Hank Garland.

Search YouTube for “Hank Garland - Sugarfoot Rag” to see Garland playing his signature tune.