ZT Amplifiers Lunchbox Junior January 2013

Touring isn't getting cheaper. Nor are practice spaces, detached soundproofed homes, or vans for hauling a small army's worth of gear. Given these truths, compact gear is more interesting and essential, than ever. So we're thankful ZT Amplification keeps making ever-smaller and great-sounding amps. The Junior is so small you could stuff it in a suitcase with your socks and set off on a European tour without checking an extra bag. That kind of portability opens up a lot of gigging possibilities—all for the cost of a good stompbox. How could a working guitarist not be thrilled?

$149 street, ztamplifiers.com

G&L Tribute M-2000

Muscle and value—that’s the M-2000 in a few words. But you could use many more in praising this affordable G&L. Reviewer Dave Abdo commended the comfort and playability as “simply stunning.” He also praised the intuitiveness and fidelity of the pickups and preamp, as well as a build quality that rivals much more expensive instruments. For anyone who’s longed for a G&L but found the price a little steep, the Tribute M-2000 is worth a look.

$699 Street, glguitars.com

Recording King RO-310 February 2013

A good OOO or OM is the acoustic-guitar equivalent of your favorite baseball glove—it’s got that just-right fit, it’s capable of both routine and spectacular plays, and in the best of times it’s like an extension of your own fingers. The Recording King RO-310 delivers each of those qualities, but at a price that we’ve rarely seen for an OM or OOO this good. Like any OM, it’s the essence of balance, but it’s the fact that it won’t knock your bank account out of balance that makes it Premier Gear.

$499 Street, recordingking.com

PRS 408 Maple Top February 2013

In 2011, PRS issued limited editions of the Custom 24 and Studio models that many considered the finest of the breed. Apparently, Paul Reed Smith decided those guitars were too good not to share, because the 408 Maple Top is essentially a production version of the maple-topped Private Stock instruments. As Jordan Wagner noted, it’s a guitar that can be “almost anything you want it to be.” With all that potential on tap, we’re excited to know what classic performances will emerge from this guitar in the years to come.

$2,990, street, prsguitars.com

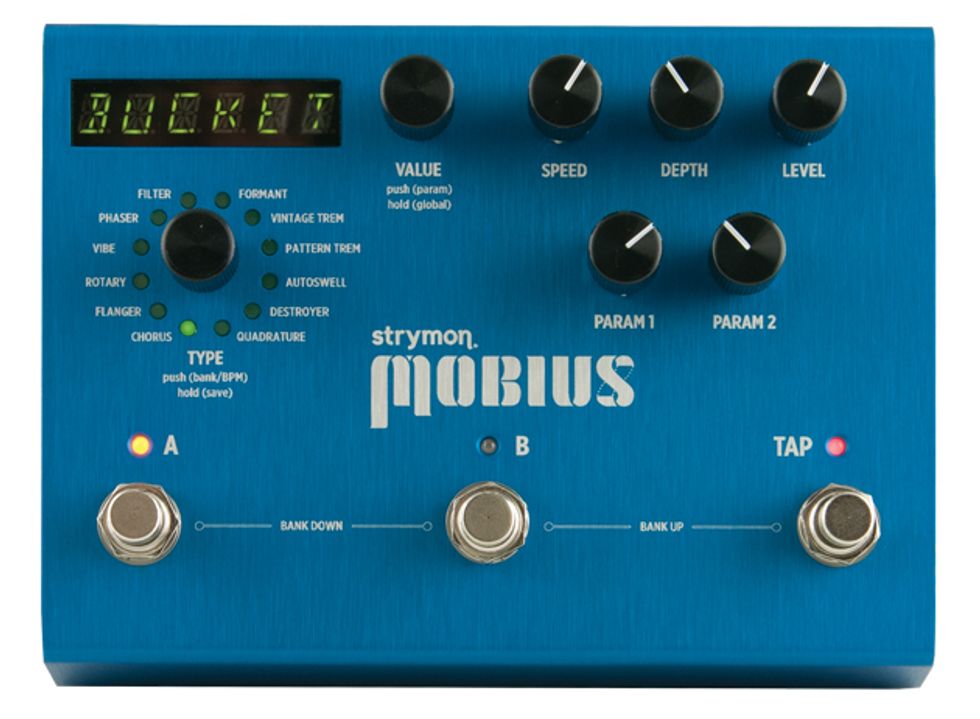

Strymon MobiusMarch 2013

This outfit of vintage tone fans with turbo digital know-how keeps on delivering stomps that sound amazing and invite deep musical exploration. The analog purists on our staff tend to be blown away by how convincing these pedals sound, and the digital-loving nerds among us love the endless options and MIDI versatility. But the essence of the Mobius is the ability to generate crazy-good emulations of modulation effects that have stumped DSP engineers, well … forever. Nice work, Strymon—again!

$449 street, strymon.net

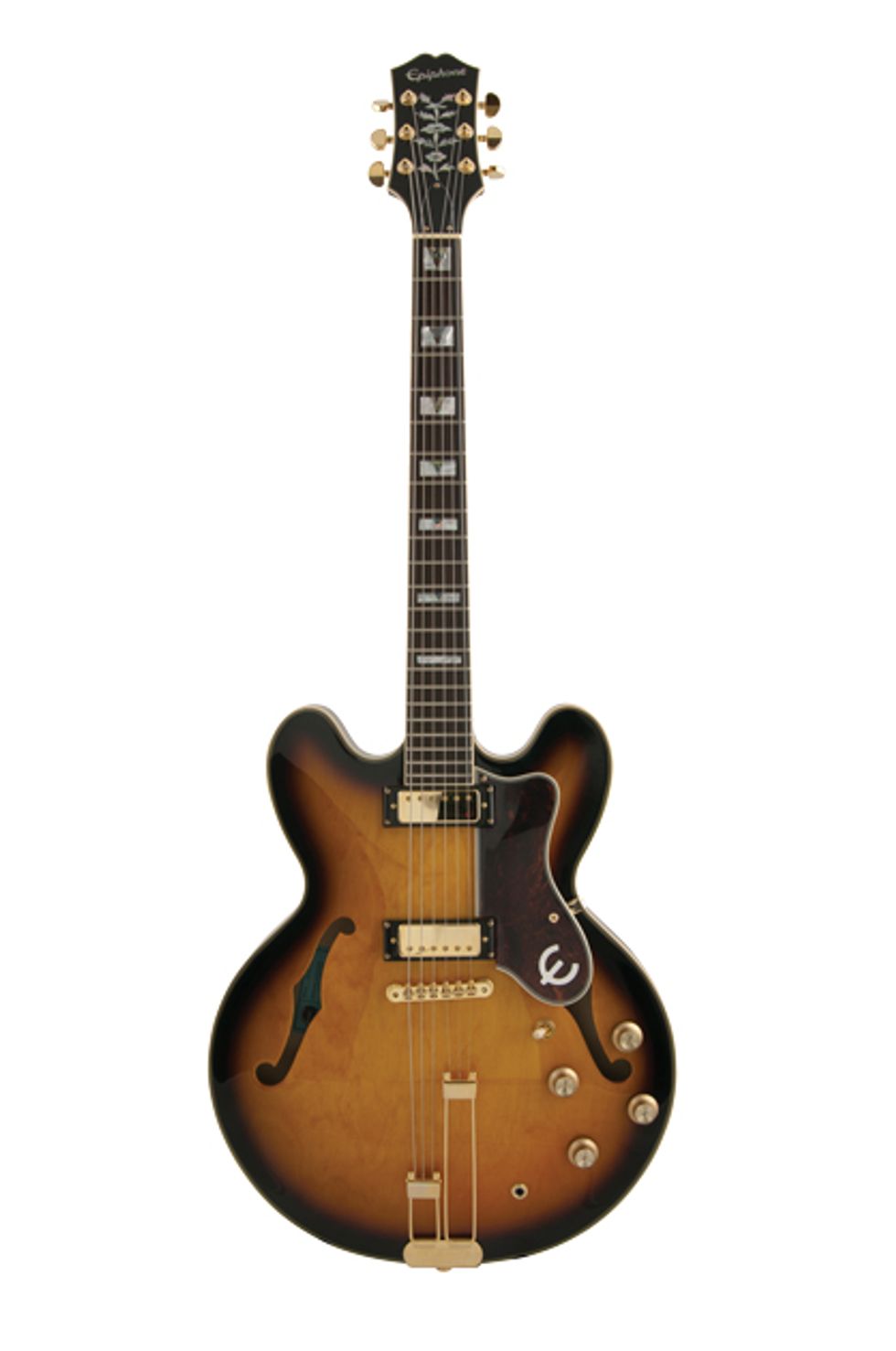

Epiphone '62 Sheraton E212T March 2013

Classy, classic, and just plain killer to play, the Sheraton had to be one of the finest luxe-for-the-bucks experiences we had all year. The U.S.-made Gibson mini-humbuckers made the Sheraton a willing partner for everything from Stones raunch to uptown Wes Montgomery-style tones. If you’re into this style of guitar, it would be hard to find a cooler piece of wood to hang around your neck—especially at this price point.

$779 street, epiphone.com

Mesa/Boogie Grid Slammer March 2013

Fear not, the Grid Slammer is not a super villain’s plot to undo the nation’s power infrastructure. It is, however, one hell of an overdrive—capable of kicking your amp into realms ranging from sweaty blues to medium-gain bliss. But it’ll also add an aggressive, singing quality to heavy leads and make any on-the-fence tube amp sound mean enough for the most evil super villain.

$179 street, mesaboogie.com

Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Bass Big Muff Pi April 2013

As reviewer Jordan Wagner noted, some of the mightiest bass tones in the galaxy come from combining a towering bass amp and a Big Muff. But Electro-Harmonix’s latest addition to the bass Muff family takes the impressive potential of that combination several steps further—adding noise gate, dry blend, and switchable crossover features that yield (get this) a more nuanced Bass Big Muff. Considering that a bass and Big Muff are typically about as subtle and nuanced as a B-52 raid, we consider this an award-worthy achievement indeed.

$118 street, ehx.comhttps://www.ehx.com

Carr Impala April 2013

Steve Carr’s work over the last decade has been consistently excellent. There’s not much in the amp-o-sphere he hasn’t tried: AC-like EL84 circuits, Deluxe-inspired 6V6 amps, and EL34-driven combos built for cranking out the heaviest rock. The new Impala is built in homage to the blackface Bassman, and like that classic workhorse it’s a beautiful blank slate. Reviewer Alex Maiolo called it “one of the finest rock amplifiers I’ve ever had the pleasure of playing.” But considering how much more the Impala can do, a Premier Gear award is a no-brainer.

$2,490 street, carramps.com

Bogner Ecstasy Red and Blue May 2013

For players fond of post-’70s hard rock and metal, Bogner’s Ecstasy amps are a little like a Mercedes-Benz—objects of lust, but also trusted to deliver and last. For those who can’t afford the original amp, the Red and Blue stompboxes gets you remarkably close to that coveted Bogner sound. The Blue is the tamer of the two, delivering exceptionally defined low- to mid-gain tones, while the beastlier Red is geared for British-style metal.

$299 (each), bogneramplification.com

Eastman AR371CESB May 2013

Eastman’s archtops, semi-hollows, and acoustics have impressed us with regularity over the years. But Adam Perlmutter found the company’s ES-175-inspired AR371CESB to be a top-quality, beautiful-sounding archtop equally adept at rowdy rock and sophisticated jazz. At just under 800 bucks, he also found it to be a value “nearly impossible to beat.” Keep the sweet deals coming, Eastman!

$780 street (with hardshell case), eastmanguitars.com

Vigier Excalibur Special 7 May 2013

Vigier is a relentlessly inventive company—which is always nice to see in a an industry that often seems chronically retro-gazing. The Excalibur Special 7 puts that inventive spirit to work in very tangible ways that yield real results. From the proprietary vibrato to the stainless-steel frets, it’s a flawlessly built marvel of playability and a monster tone machine to boot.

$3,495 street, vigierguitars.com

Way Huge Echo-Puss May 2013

Jeorge Tripps and the Way Huge crew seem almost incapable of making a bad—or even mediocre—stompbox. And the Echo-Puss is a superb analog bucket-brigade delay that lives up to Way Huge’s impressive reputation. Anyone who’s ever loved and lost a vintage Deluxe Memory Man will love this thing. Its combination of gorgeous analog tones, smart-sized enclosure, and rugged utility make it a Premier Gear shoo-in.

$169 street, wayhuge.com

Diezel D-Moll May 2013

The 100-watt, KT77-driven D-Moll starred in our Monsters of High Gain roundup because of its superior definition and midrange detail. But lest you think Diezel traded civility for ferocity, keep in mind that our reviewer emerged from 10 rounds with the D-Moll calling its overdrive “pretty intimidating.” Indeed, the D-Moll may be a cultivated monster, but it’s a monster nonetheless.

$2,999 street, diezel.typo3.inpublica.de

Ibanez AFJ957 May 2013

Seven-string archtop players could safely be called a niche market, but that’s what makes the AFJ957 so impressive. It takes commitment and thoughtful design and execution to make a niche guitar like this so affordable. The result, as Joe Charupakorn put it, is a guitar that’s “not just a great guitar for the price, but a great guitar period.

$799 street, ibanez.com

Spaceman Saturn V Harmonic Booster May 2013

This Portland, Oregon, pedal manufacturer riffs heavily on ’60s-era NASA design aesthetics, but its pedals also seem built to space-faring specs. They are rock solid and, in the case of the Saturn V Harmonic Booster, a heavy-duty musical asset. This incredibly complex boost pedal enhances picking dynamics, responds to input changes from your guitar, and delivers cool overdrive tones that are full of character. Plus, it looks like you just ripped off a component from an Apollo capsule to put on your pedalboard!

$219 street, spacemaneffects.com

ValveTrain Trenton June 2013

This boutique amp outfit’s mantra seems to be that top tones need not mean top dollar. Though ValveTrain’s wares aren’t cheap, they’re almost always a great value for the quality and sound they deliver. With the beautiful-looking Trenton, Valvetrain delivers great tones via four switchable voices that, as reviewer Derek See described it, go from “clear to Crazy Horse.” For a very reasonable 1,400 bones, we’ll just call it killer!

$1,399 street, valvetrainamps.com

Dingwall Super P June 2013

As iconic and familiar as Fender’s Precision bass is, it’s unusual to do a do double take when you see an instrument with those same familiar lines. But with its fanned frets and biomorphic headstock, it’s hard not to stare at Dingwall’s Precision-inspired Super P. When reviewer Steve Cook wasn’t drooling over its cool looks, he was marveling at the playability, ergonomics, attention to detail, and range of sonic possibilities—which he called “downright incredible.”

$2,730 street, dingwallguitars.com

Ibanez ES2 Echo Shifter June 2013

As obsessed as we get about how stompboxes sound, it’s easy to forget that great pedals can be instruments in their own right. Take the Ibanez Echo Shifter: That control layout—three adjacent knobs, two switches, and a big slider—makes this one of the most fun-to-use echo units since the Maestro Echoplex. But they also make it incredibly versatile, expressive, and musically responsive. Whether you use it as a tool for freaking out or playing it cool, it comes at a price that make it dang-near irresistible.

$149 street, ibanez.com

Nik Huber Rietbergen Standard June 2013

We’ve had the good fortune to spend some quality time with Nik Huber and check out how they do things at his shop in Rodgau, Germany. So we were hardly startled when reviewer Ben Friedman returned a rave review of Huber’s sumptuous semi-hollowbody, saying the tones from the Häussel pickups “were bound to dazzle.” Considering this is probably the most beautiful guitar we’ve seen yet from this remarkable builder, we’re not about to disagree.

$7,325 street, nikhuber-guitars.com

Amptweaker TightFuzz June 2013

This pedal from amp guru James Brown is one of two bass fuzzes in our Premier Gear lineup this year. And attentive bass-gear manufacturers out there would do well to take note of how a good bass fuzz can be an unexpectedly versatile texture. The Tight Fuzz does it with a control set that’s sure to look busy to old-school players, but we’re betting it only takes a few minutes to change the minds of those fence sitters and curmudgeons, because the Tight Fuzz has the goods to transform your tone.

$220 street, amptweaker.com

Ibanez Iron Label RGIR20FE July 2013

You can’t really fake a good shred guitar, because even shredders on a budget have no time for crappy action, dodgy playability, and squishy, unresponsive electronics. Ibanez gets that. And in the form of the Iron Label, they’ve delivered a superb, affordable shred machine. We found the quality and playability astounding for a 600-dollar guitar. That, plus a surprising adaptability, helped make this Ibanez an easy choice for a Premier Gear award.

$599 street, ibanez.com

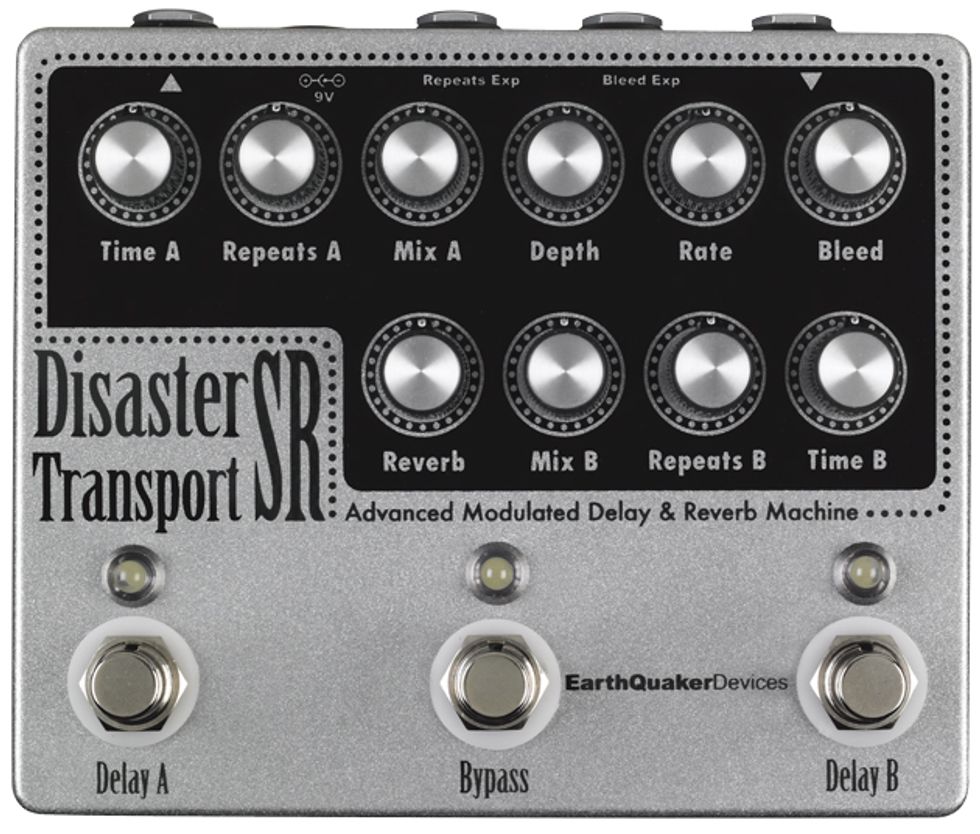

EarthQuaker Devices Disaster Transport SR August 2013

EarthQuaker Devices is a company with gumption, derring-do, and a music-first sense that results in pedals that can be practical and bizarre—often all at once. Case in point—the Disaster Transport SR. Yes, you can dial this dual delay up (with surprising ease) for a conventional, parallel long and short delay. But it takes but a few tweaks before you’ve converted this silver-flake delight into a peyote voyage in a box.

$345 street, earthquakerdevices.com

Reverend Kingbolt August 2013

Despite boasting a roster that includes adventurous and virtuosic players like Reeves Gabrels and Pete Anderson, Reverend’s more traditional-looking body lines can often give the impression the company has a retro agenda. The Kingbolt, however, could change that perception for good. With hot, no-cover humbuckers, a 12" fretboard radius, Wikinson trem, and graphite nut, it’s an unquestionably metal-geared machine. While reviewer Joe Charupakorn found it varied enough to deem it “a gold mine of tonal possibilities,” we suspect a lot of players are going to dedicate their Kingbolt to getting heavy above all. So much for that retro agenda.

$1,079 street, reverendguitars.com

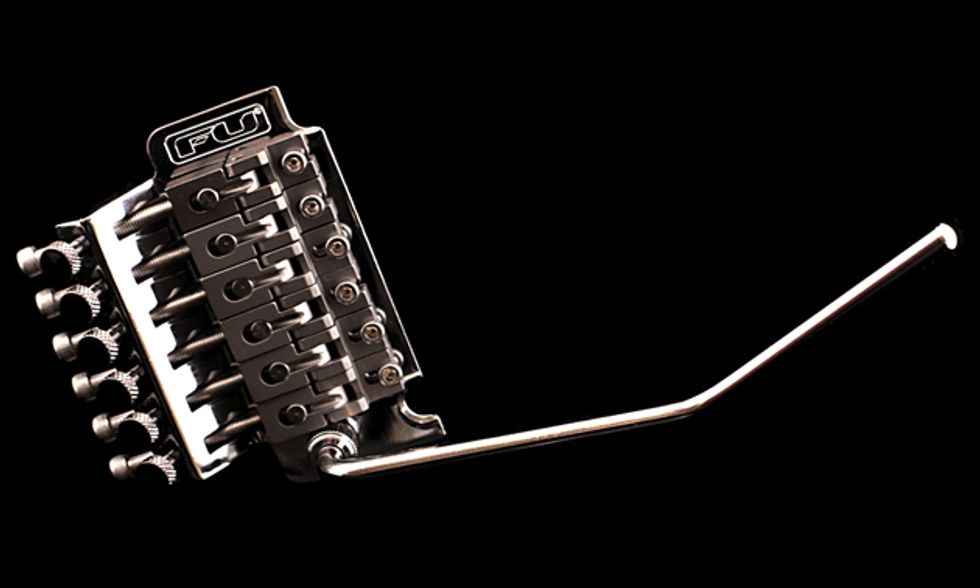

FU-Tone High Performance Bridge Packages August 2013

Dedicated shredders obsess over guitar details that’ll never even occur to many other players. For these demanding and ultra-specialized players, little things add up to big tone and playability dividends. Yes, at least one of the packages here is built around a titanium tremolo block, yet reviewer Gerry Ganaden found the difference in tone profound. And for downright religious tone hounds, the payoff will be worth every penny invested.

$320 street (Standard Upgrade Package), $923 street (Full Titanium Package), fu-tone.com

Jaguar HC50 August 2013

The Jaguar HC50 walked away with a Premier Gear award largely for its mastery of the sound/simplicity equation. Four knobs, a couple of EL34s, a good 12" speaker, and—voilà!—you’ve got a palette of tones that ranges from jangly and airy to monstrous. Reviewer Matt Holliman also noted that the HC50 took to just about every effect he tried “like a fish to water,” which might make this the finest blank canvas for sound sculptors we played all year.

$2,029 street, jaguaramplification.com

Lakland Decade 6 August 2013

Six-string basses are odd birds, but for players willing to investigate the potential of these instruments, the musical payoff can be big. Lakland’s Decade 6 is, like most every Lakland bass, beautifully built and executed. Mate that quality with the ability to move from Spaghetti-Western baritone sounds to powerful, thumping low end, and you have a serious studio and stage secret weapon—not to mention a means of expanding your vocabulary in unexpected ways.

$3,250 street, lakland.com

Epifani AL 112 August 2013

The AL 112 bass combo makes us wonder why the guitar industry often seems so dang obsessed with the days of tweed cabs and carhops (cool as those are). The Epipfani looks vaguely like a circa-’72 vision of the future, but it takes a very different approach to bass-amp construction—using an aluminum cabinet to create a very light, tough, practical, and big-sounding bass amplifier. That’s the kind of forward thinking we can get behind.

$1,599 street, epifani.com

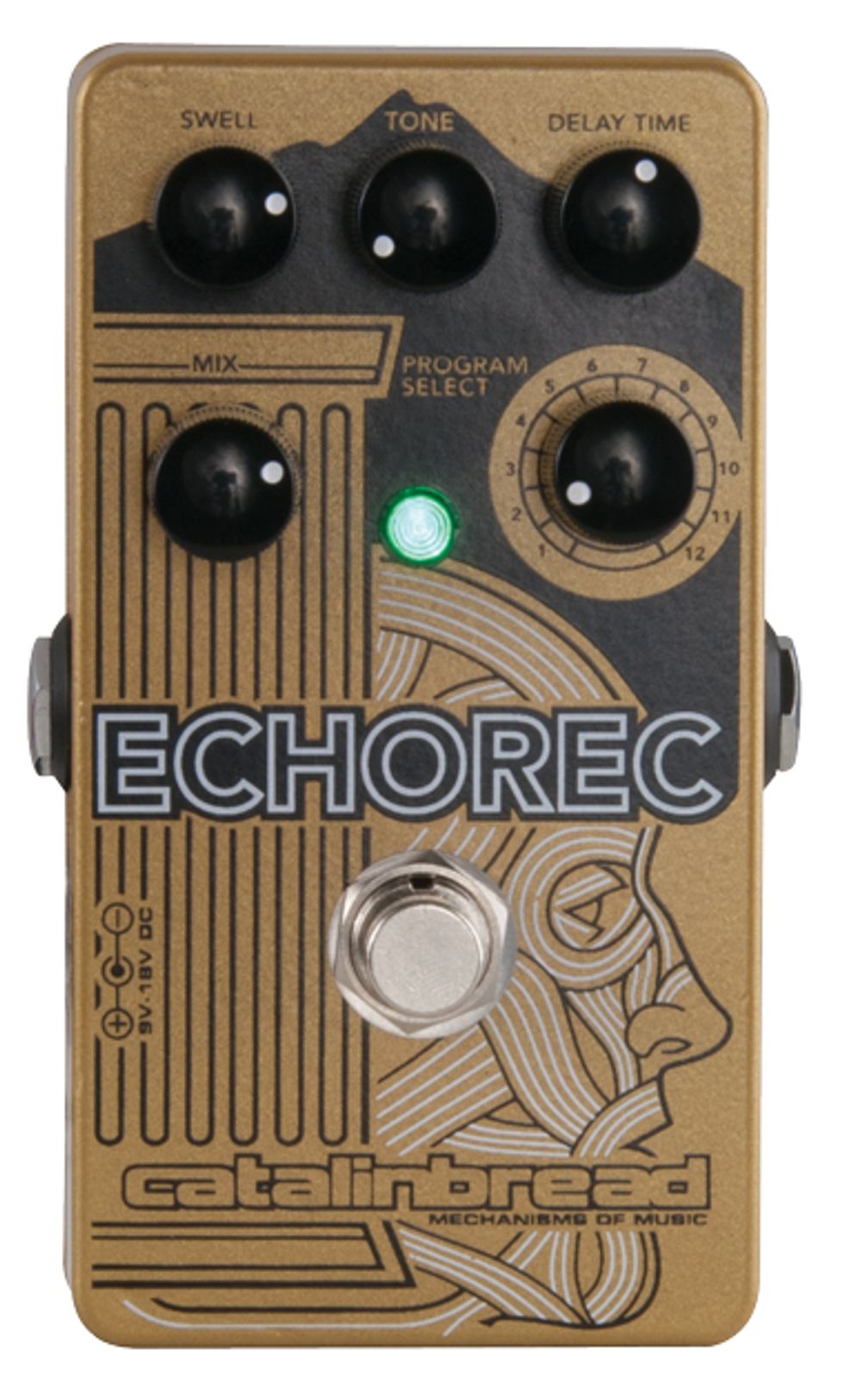

Catalinbread Echorec September 2013

The original Binson Echorec is perhaps most legendary because of its role as the echo unit that powered early Pink Floyd work. Those associations aside, the Binson was a gloriously quirky and unique machine with a very distinct musical personality. Catalinbread’s own Echorec uses DSP technology rather than the clunky mechanicals of the original to achieve its lush voice and superb rhythmic delays. But delay fiends and Floyd fanatics aren’t likely to give that much more than a passing thought once they plug this unit in and experience its liquid, spacious repeats.

$230 street, catalinbread.com

Fargen Blackbird VS2 September2013

The 40-watt Blackbird, as the name cheekily suggests, pays homage to Fender’s mid-’60s blackface era. But it’s counted among this year’s award winners for delivering a super-responsive tone-shaping section and an incredibly pedal-friendly voice. If you’re ready to retire your heirloom blackface, you’d have a hard time finding a better replacement.

$2,650 street, fargenamps.com

Death by Audio Thee Fuzz Warr Overload October 2013

Known for their bizarre contraptions of aural destruction, DBA’s latest fuzz is a collaboration between two chaos-loving artists—the Death by Audio team (which includes A Place to Bury Strangers’ Oliver Ackermann) and Thee Oh Sees’ John Dwyer. Not surprisingly, it’s capable of producing a brutalizingly powerful fuzz tone. But what makes the DBATFWO Premier Gear is its surprising flexibility—and even civility! The onboard treble boost is a perfect match for the Muff-like fuzz, and the tone control has considerable sound-sculpting power, making this fuzz a killer whether you need a slik glove or a wrecking ball.

$225 street, deathbyaudio.com

Dunlop Fuzz Face Mini Germanium FFM2 October 2013

While we were pretty excited by the convenience of the smaller Fuzz Face Mini Germanium, in the end it was the amazingly authentic vintage Fuzz Face tones and dynamic interactivity that knocked us off our feet. Senior editor Joe Gore—a seasoned Fuzz Face user if there ever was one—declared, “you’d be hard-pressed to find a Fuzz Face that sounds better at any price.” But with all that tone in a new pedalboard-friendly compact enclosure, this new Fuzz Face excels at being practical and musical.

$129 street, jimdunlop.com

Pigtronix Quantum Time Modulator October 2013

Pigtronix makes impressive-sounding, sometimes complex pedals. But with the Quantum Time Modulator, it delivers a typically inventive and rich-sounding fusion of chorus and vibrato in a compact enclosure that’s beautifully simple. The sum is a modulation unit that ranges from subtle to downright insane with a few quick twists. This ability to appease mellow texturalists and freakishly experimental players alike make this pedal a Premier Gear no-brainer.

$199 street, pigtronix.com

TC Electronic PolyTune 2 November 2013

TC’s original PolyTune tuner wowed the world with its ability to check the pitch of all six strings with a single stroke or switch to single-string chromatic mode with the pluck of one string. This newest incarnation adds a more accurate strobe mode, a super-bright readout, and a sensor that will adjust to prevailing light conditions. Who knew a little tuner could do so much or make our playing lives so much easier?

$99 street, tcelectronic.com

When we editors at Premier Guitar decide what gear to review, our overarching guideline is pretty simple: Check out the stuff that you will find compelling and useful in your creative quest. We base that on both the constant feedback we get from you online (via email, Twitter, Facebook, etc.), as well as what we can intuit by reading between the lines of your requests and putting it in context with new stuff you may not have heard about yet. As a result we see a lot of really nice stuff.

So when one of our editors or contributors is struck by a convergence of value, quality, and sound that adds up to being Premier Gear worthy, it’s a safe bet we’re talking about something special. It’s fun and satisfying to encounter these especially excellent guitars, basses, amps, effects, and accessories—doubly so because so many of our award winners come from small shops and tiny bands of craftspeople who are in the same position many of the mainstream names you see alongside them were decades ago. There aren’t many industries out there where multimillion-dollar giants and little guys can share the spotlight, and we love being part of it.

Big or small, the manufacturers represented in this compendium of gear that’s won our coveted Premier Gear Award in 2013 have done very cool work. Some of it is traditional but superbly executed. Other pieces are here in no small part because their creators took chances. No matter the path, though, the end result is gear that sounds great. What you do with it is up to you and your imagination. But we’re quite confident the stellar products here will spark more than a few ideas.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)