If you've spent any amount of time on guitar-gear forums, you know they can often devolve into pretty abrasive battles of opinion. Even when a thread starts out with the best of intentions, it's not uncommon for it to morph into the online equivalent of a mythical Hydra. Forum administrators attempt to clean things up and lock out the more abusive commenters, but once they cut off one of the creature's heads, two more appear.

Of all the forum topics that can inspire such heated debate, few inspire more passion, awe, and vitriol than a guitar pedal named after a different sort of mythological creature. Launched in 1994 at the front end of the modern-day boutique-pedal boom, the Klon Centaur overdrive was immediately met with critical acclaim. So much so that it's ironic how much the pedal named after the half-human, half-horse creatures from Greek legend has since developed such a complex mythology of its own. And the fact that this seemingly mundane, 3-knob stompbox is used by such high-profile players as Jeff Beck, John Mayer, Joe Perry, Nels Cline, and Matt Schofield only compounds matters. Never mind the fact that the majority of the circuit comes encased in epoxy.

We recently spoke to Klon's Bill Finnegan about the origins of the Centaur, his new KTR design—which made a (naturally) limited debut in October of 2012—and how an overdrive pedal can fetch more than $1,000 on the used market and inspire such emotionally charged reactions.

Birth of a Centaur

In the 1980s, Bill Finnegan played in a band where he plugged his Telecaster straight into a Twin Reverb turned up as loud as the soundman would permit. In bigger Boston-area clubs, the Twin's volume would be at 6 or sometimes even 7, but in smaller places Finnegan could usually turn it up to only 3 1/2 or 4. The latter still sounded good, but not as harmonically rich as when the amp was working harder. Although it didn't occur to him at the time, a pedal that would give him the sound of a cranked amp is exactly what he needed.

Finnegan recalls that, in 1990, guitarists began chasing after out-of-production Ibanez Tube Screamers in droves. He'd heard about a guy who was selling two TS9s, and—hoping one of the little green pedals would help make his Twin sound like it was at 6 when it was only at 4—he went to check them out. It immediately became clear that Tube Screamers were not for him.

Finnegan built Centaurs—around 8,000 in total—by hand, on a cheap folding card table in a succession of small apartments for 15 years.

“[The TS9] compressed the transient response of the original signal a lot, had a midrange character I didn't like, and subtracted a noticeable amount of bass response from the signal as well," he explains. The same seller also had a TS808 that he wasn't selling. And, though Finnegan thought it sounded a little better than the TS9s, he still felt it had the aforementioned shortcomings. What he really wanted was a big, open sound, with a hint of tube clipping—a sound that would make you unaware a pedal was involved.

That's when Finnegan starting looking into creating a new design that would meet those criteria. He recruited a friend who'd just graduated from MIT with an electrical engineering degree. Though both had day jobs, for the next couple of years they got together once a week and tried to push the ball down the field. Within the first year, they'd developed prototypes that were much closer to what Finnegan wanted than a Tube Screamer, and various guitarists in the Boston area encouraged them to go into production so they could buy their own. But Finnegan felt the circuit could still be improved, so he and his partner kept working.

Eventually, the MIT friend bought a house in the suburbs and the distance made it harder to work together. Finnegan later partnered with the late Fred Fenning (who tragically passed away in a plane crash in the mid '90s)—another MIT grad whom Finnegan says was brilliant and very determined. Although Fenning had never designed an audio circuit and had no real interest in music, he was exceptionally good at finding ways to give the circuit what Finnegan thought it needed at any given time. Finnegan says Fenning deserves a lot of credit for the circuit in both the Centaur and its successor, the KTR.

Photo by Sarah Pollman

The entire design process took four and a half years, and when the pedal debuted at the end of '94 Finnegan was soon very busy trying to keep up with the demand—building, testing, and shipping the pedals as a single-man outfit.

Evolution of the Legend

From that point on, demand for Centaur pedals grew. Finnegan says he typically worked 55–60 hours per week in effort to keep turnaround times as short as possible, though he was hindered by the fact that the circuit was very labor intensive and time consuming. He also says it was more expensive to build than most other pedals due to the fact that everything from its cast enclosure to its knobs, pots, and sheet-metal bottom were custom crafted. Finnegan estimates the aggregate cost of a Centaur as seven to eight times that of a pedal built with off-the-shelf parts.

“For the last seven years or so of Centaur production, the retail price was $329," says Finnegan, “and to be honest, my profit margin was not very sensible—no real business person would have considered, for more than a moment, doing what I was doing for the return I was receiving. Also, given that I live in Boston, it was impossible for me to hire people and expand: Real estate here is in short supply and very expensive, so there was no possibility of my renting commercial space to set up an actual shop."

Finnegan built Centaurs—around 8,000 in total—by hand, on a cheap folding card table in a succession of small apartments for 15 years. In addition to the modest returns from his efforts, Finnegan says he felt immense stress as he tried to oblige those who wanted a Centaur but didn't want to pay the inflated price used specimens were fetching because of the 12- to 14-week turnaround time for a new one. It gradually became clear to Finnegan that the situation was unsustainable.

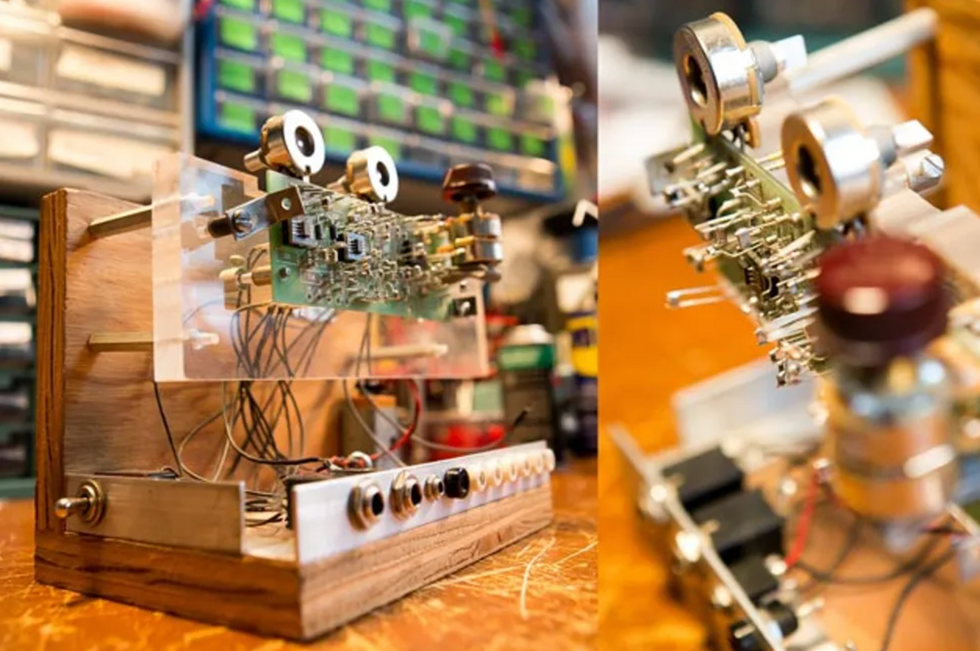

“These two photos show my testing jig for Centaur boards, with one of my experimental boards on it," Bill Finnegan shares. “The experimental boards have sockets for every component in the circuit, which enables me to listen to any particular component and then swap it out for a substitute while keep everything else the same. This experimental board is the one I used for developing the KTR. Unlike the Centaur which had through-hole components with leads, I wanted to use surface-mount components for the KTR, which meant that my assistant, John Perotti, and I had to spend an enormous amount of time soldering through-hole leads onto hundreds of very small surface-mount components so that we could evaluate them and choose the ones that would make the KTR sound the same as the Centaur did."

Photo by Nolan Yee.

“I was going to have to kill it before it could kill me," Finnegan recalls. In 2008, he began working on a ground-up redesign that had to meet the following criteria: It had to be straightforward to build, so that any good contract manufacturing firm would be able to do the job easily and well. It had to be rugged and reliable. It had to be a design with no hookup wires whatsoever, and with a modular footswitch assembly so that faulty footswitches could be replaced in a few minutes. It had to be considerably smaller than the Centaur. Except for the all-important clipping diodes, it had to have surface-mount components, which take up less space on a board than traditional through-hole components. Finnegan also wanted to prove—to himself and to those who said it couldn't be done—that, with careful component selection and smart board layout, he could design a successor that would sound exactly the same as the Centaur.

“This turned out to be quite a challenge," Finnegan says. “My assistant, John Perotti, and I spent almost two years listening to different surface-mount capacitors in various places in the circuit before I felt this had been achieved." Lastly, he wanted the new unit to be visually unique—a tall order, given that the unit would be housed in a standard enclosure.

I don't have any overall preference for single-coil guitars or humbucker guitars myself. I like pretty much everything under the sun in the way of electric guitars, and over the years I've owned a bunch of very different ones.

The one new feature Finnegan wanted to incorporate was a switch that enabled the player to choose the buffered output of the original Centaur or a true-bypass output. “Without the buffer there is a very noticeable degradation of the signal due to the capacitance inherent in guitar cables," says Finnegan, “but some people prefer it, so I wanted to provide that option in the new unit." He quickly adds, “My good friend Paul Cochrane—of Tim and Timmy [pedals] fame—was the guy who designed the switching circuitry, so a tip of the hat to Paul."

It took a long, long time to finish the KTR. And though Finnegan says it was much more difficult than he expected, he feels it has achieved all of his design objectives. “It sounds the same as the Centaur, takes up considerably less space on a pedalboard, is less expensive, and it's distinctive aesthetically—it's got the Klon thing going on." He laughs, “Whatever the Klon thing is."

You obviously have high expectations from your designs, though you're also perplexed by the reactions it inspires. What do you want people to see in Klon?

What I want people to expect from me and from Klon are designs that are exceptional in the literal sense of the term—designs that are conceptually sound and well executed. Designs that are unique and not to be expected from any other designer, no matter how talented.

When you were designing the Centaur, did you begin with any assumptions about players who'd be interested in it?

I was working from the assumption that there were a lot of guitar players with really good guitars and really good amps who were looking for an overdrive pedal that—whether it was adding dirt or not itself—wouldn't mess up what they already had and liked. Given the popularity of the Centaur and now the KTR, I would say that this has been borne out.

In your opinion, do the pedals work better with single-coils or humbuckers?

Neither. I don't have any overall preference for single-coil guitars or humbucker guitars myself. I like pretty much everything under the sun in the way of electric guitars, and over the years I've owned a bunch of very different ones. Each of them has its own particular thing going on, and when I was working on the design of the circuit I was always thinking about how it could be more effective in preserving and accentuating the essence of whatever instrument it was receiving the signal of.

What can you tell us about Centaur units that occasionally turn up on eBay with the claim that they are “new, with full warranty"—are they fakes?

I have a very close friend who is a single mom and whose job doesn't pay all that well. Every now and then she needs a little help, financially. I'm aware of what the used units are selling for, so at some point after I discontinued the Centaur it occurred to me that—if and when she needed me to—I could build a Centaur and give it to her to sell on eBay and use the proceeds to keep going. This has worked really nicely, and I'll continue to do it for as long as my old Centaur parts last. Since I discontinued the Centaur, a lot of people have asked me whether I'd consider building one for them—sometimes offering me pretty substantial amounts of money—but I'm not going to do that. The only Centaurs I build anymore are the ones I build for her, and I don't make or collect a single cent from them.

Klon builder Bill Finnegan wanted to include this text—which refers to the dialogue surrounding his famed Centaur design—on the casing of his new KTR pedal. “It's a wry observation that I can't be held responsible for the overheated emotions that have been introduced into various Klon debates since the earliest days of the Centaur," he says. “I knew that in using that text I'd be stirring things up some, but I thought it would be interesting and fun to see how, in reacting to it, people would self-select into either the 'love it' or the 'hate it' group."

Photo by Nolan Yee.

Do you think Centaurs will retain their high value now that the KTR is available?

Yes, in general I think they will. They're collectible and—with the one small exception I just mentioned—no more will be built, unless I'm very mistaken. For almost everyone, the KTR is a much more sensible option now: It sounds the same, it's much smaller, it's way the hell less expensive—$269 retail—and you don't have to worry about losing something that's worth $1,000 or $1,500 or $2,000 if it's stolen. On the other hand, the Centaur has something of its own that people really like and are willing to pay serious money for. The design has achieved a certain status—I would use the analogy of old, custom-colored Marshalls. I have two small-box, 50-watt Marshall Lead heads—model 1987s: One is a black-Tolex, aluminum-panel head from 1970, and the other is a red-Tolex, plexi-panel head from 1969. They have the same circuitry and sound almost identical, but of course the red one is worth way more than the black one. I like cool, distinctive things as much as the next guy, so I'm not in a position to criticize someone for being willing to pay more than I myself would, or more than most people would, if they want it that much.

What are the demographics of the typical Klon user?

It seems to be more or less everyone. Baby-boomer guys who are still only interested in the music they grew up with, but also a lot of younger, indie-rock people, and also a number of musicians whose work is more experimental and can't be easily categorized.

What can you tell us about the germanium diode you like so much in your circuits?

In 1993 and '94, when it was clear that Fred and I were getting close to producing what I thought was the full measure of what our circuit was capable of, I started buying quantities of every diode I thought might be at all suitable for the head-to-toe pair that clips the signal, except for when the circuit is in clean-boost mode. This was pre-internet, so I was going to the public library, looking up distributors in the Thomas Register, and then calling those distributors to find out what they had—email was still in the future then! I started out ordering both germanium and silicon diodes, but pretty quickly I began concentrating on the germaniums. Usually, though not always, they sounded more natural to me than the silicon ones did. After months and months of listening, I felt a particular new-old-stock germanium diode sounded best in the circuit, so I thought I should buy as many of those as I could afford. Eventually, I found a distributor that had a significant quantity of them. They were stocking them for a huge OEM, who—without any warning, I gather—stopped using that part. I bought them all at a good price. The distributor was thrilled to be able to sell them and not have to eat them.

Does the KTR have the same diodes?

Yes, the KTR has the exact same NOS diodes as all Centaurs did.

Since I discontinued the Centaur, a lot of people have asked me whether I'd consider building one for them—sometimes offering me pretty substantial amounts of money—but I'm not going to do that.

What is it you like about the sound of that diode when it clips?

It's a little more complicated than that, because the diode clipping happens on top of some op-amp clipping in the main gain stage. So it's op-amp clipping, then diode clipping. But to answer your question, this particular diode in the head-to-toe pair in the circuit just produces a very natural-sounding distortion in terms of the harmonic response. It's not harsh, but it also doesn't round off the highs excessively. It doesn't compress the signal as much as many germanium diodes seem to, but on the other hand it provides a little bit of what—to me—is exactly the right kind of compression.

Which other pedal makers are using this particular diode?

To the best of my knowledge, no one. It's a part that's been out of production for decades now, so even if someone else could identify it, I seriously doubt they'd be able to find any—I've tried a number of times myself.

So what are you working on now?

Lately, I've been focused almost entirely on putting together a good long-term arrangement for production of the KTR. This kind of thing has always been more of a challenge for me than it seems to be for anyone else, but I admit that I do have requirements—particular things I insist on—that few, if any of those other people have, so I guess that the increased difficulty is to be expected. I'm not saying that my stuff is necessarily higher quality than anyone else's, but rather that my criteria are somewhat different and that therefore the process is necessarily also somewhat different.

What is the current availability of the KTR?

The unit should be widely available—through dealers both here in the U.S. and in various other countries—by the time this interview is published. Hopefully by then I will have found time to get some kind of updated Klon website going, which of course will have contact info for the current dealers.

The top of the KTR features some text that's apparently causing controversy with some buyers: “Kindly remember: The ridiculous hype that offends so many is not of my making."

Lots of people got the point that I was trying to make and really enjoy the text, while other people find it off-putting or even insulting. It's a wry observation that I can't be held responsible for the overheated emotions that have been introduced into various Klon debates since the earliest days of the Centaur. I knew that in using that text I'd be stirring things up some, but I thought it would be interesting and fun to see how, in reacting to it, people would self-select into either the “love it" or the “hate it" group.

Photo by West Warren.

What does the future hold for Klon?

I've been thinking about this quite a bit lately. Part of me wants to work on design ideas I have—finish those designs to my satisfaction—and then make the resulting products available. The other side of me wants to either refrain from working on those ideas or work on them, finish them to my satisfaction, and then not put the resulting products out. As you may or may not know, many unscrupulous people have expropriated my hard work on the Centaur and KTR circuits and are selling pedals that incorporate my circuit—and in at least some cases, they're making a lot of money. And apparently there is nothing I can do about this from a legal standpoint.

Quite aside from the money they're making from my work, there's the question of what those pedals sound like. My understanding is that a number of those people are claiming their versions sound “identical" to mine, which—for reasons not only pertaining to the clipping diodes you asked me about—I think is very unlikely. Whatever expertise those various people may have, I'm going to go out on a limb and state my belief that it's not likely to be a good or sufficient substitute for the experience I have with the circuit: I co-designed it, I've hand-built and listened to about 8,000 Centaur units, I spent two years working hard to make sure the KTR would sound the same as the Centaur, and I've put almost 25 years of my life into it. If those other guys' pedals don't sound right, then of course Klon's reputation—and my reputation as someone who cares deeply about the quality of what goes out under the Klon name—will inevitably take a hit.

So my feeling is this: If any new product I come out with will be ripped off immediately after its release, and if unscrupulous people will again be making money off of my work, and if on top of that Klon's reputation and my own personal reputation will be at risk every time someone decides to put out his own version of one of my designs, then where is my incentive to release anything new at all? Over the past few years, I've talked with a number of other pedal designers about this stuff—good people who design their own circuits, and whose circuits have also been ripped off—and we all agree there is now an enormous disincentive for any of us to create and release new products.

From what I understand, a lot of the people posting on various online forums seem to feel that it's a wonderful thing for the pedal consumer to have more choices—how could that be bad? Here's how it could be bad: Maybe talented pedal designers—originators—will simply stop designing pedals and take their talents elsewhere to apply them to the design of other classes of products that can't be ripped off quite so easily.

Top 5 Klon Myths

Gear forums are regularly aglow with all sorts of comments about Klon. Here are the most common misconceptions.

- The Centaur is a slightly tweaked [insert name of extant pedal here] circuit. According to Klon's Bill Finnegan, “it's a much more complex circuit than the typical overdrive/boost circuit. These claims stopped almost immediately after it was reverse-engineered in 2007 and a schematic was posted online."

- Certain Centaurs sound better than others. Finnegan says he's heard this claim about earlier units, later ones, gold ones, and silver ones. “The fact is, under the hood they're all basically the same. In 1995 I made three small changes: I added a resistor to give the circuit some protection against a static charge delivered to its input—a change that has no sonic effect. I also had the circuit board redesigned with a ground plane for better grounding—again, no sonic effect except the potential for a little less hum. And I added a resistor to give the circuit a very small amount of additional low-mid response—I wanted it to have a little more roundness when used with, say, a Strat into a Super Reverb. I made no other changes."

- The KTR doesn't/can't sound as good as the Centaur. Finnegan says this claim arises because the KTR uses surface-mount parts while the Centaur (and most other pedals) use through-hole parts. “For two years my assistant, John Perotti, and I listened to hundreds of different surface-mount parts throughout the circuit," Finnegan explains. “While it wasn't an easy or pleasant process, we both feel—and now a lot of other people feel, as well—that I achieved my design goal: With careful component selection, the KTR sounds the same as the Centaur."

- You have to play really loud for the Centaur or KTR to sound good. “You need to have the output knob high enough that the signal hits the front end of your amp harder than your bypassed signal would," says Finnegan. “In other words, you need to use the unit as an overdrive in the literal sense of the term." The assumption here is that users are pairing the Centaur or KTR with an all-tube amp. “It's always a good thing if your amp is turned up enough to get the harmonic response and distortion that are engendered by tubes clipping and output transformers saturating. This is true whether you're playing through a 4-watt or a 100-watt amp."

- Certain clones sound “exactly the same" as a Klon. Finnegan's contention is that, given several factors—especially the rarity of the Centaur's germanium clipping diodes—it would be extremely difficult to create an identical-sounding overdrive/boost.

[Updated 12/12/21[

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.