Standing onstage at Boston’s Paradise Rock Club, 64-year-old Billy Zoom doesn’t look a day over 40. In his signature wide stance, he peers out over a sea of thrashing bodies with the vacant grin of a joker. Possibly for fear of blinding, he never once looks down at his sparkling Silver Jet as he shreds. The entire club, entranced by X’s beloved punk rock anthem “Los Angeles,” murmurs with cult-like enthusiasm, “She had to leave ... It felt sad, it felt sad, it felt sad.”

Just a few weeks earlier, not far from L.A., Zoom was in his Orange County shop, where he’s known in the industry as a jack-of-all-trades for his technical work building, repairing, and modifying tube amps—work he says he prefers to touring. “I hate that feeling right before I have to leave,” he says. “I usually don’t bother to read the itinerary or anything until a few days before so I don’t have to think about it.”

Nerves and X aside, this guy earned his stripes playing with legendary acts like Gene Vincent, Etta James, and Big Joe Turner—and in certain circles, he’s considered among the greatest players of all time. But some may not know that he spends the rest of his time tinkering with tubes in his workshop.

Billy Zoom holds his signature Gretsch Custom Shop Tribute Silver Jet model, which was part of a limited run that is now totally sold out. “Mike McCready from Pearl Jam got the last one,” Zoom says. Nearby are his special stereo model Silver Jet with TV Jones pickups, as well as a stereo amp he built. Photo by John Gilhooley

Most people know you as a guitar hero.

How did you get into building and modifying

amps?

I started getting into ham radio when I was

much younger. In 1958 I started building

kits and working with radio transmitters. I

was also playing guitar, but I had an acoustic.

In about ’62 I switched to electric and

had to have an amplifier. I started to realize

it was the same kind of stuff. The inside of

an amp made sense to me because I already

knew the radio stuff. I became the local

amp repair guy, and then in the late ’60s I

went to a vocational school for two years to

learn electronics. Basically it was training

to be a color TV technician, but it was a

really good background. It was only the last

semester that was television intense. I went

in knowing I was going to apply the skills

to working with sound. I usually kept the

poor teacher after class for an hour or two

every time, badgering him with questions

and bringing in amps.

And then you opened your first shop

in 1970?

Yeah, on the corner of Sunset Boulevard

and Vista Street in Hollywood. I do a fair

amount of general repair work to anything

with tubes, plus guitars, studio gear, and

then modifications and building my products.

I do it all. It’s kind of a mix.

And you’ve been in business ever since?

Pretty much, except for the years like ’88,

’85, when X was touring constantly and I

moved my shop to my house but was still

working in between tours.

X has been touring regularly again since

’98, right?

Yeah.

How do you go about balancing your

business with touring?

With great difficulty. I’m not here enough.

We’ve been really busy touring this year.

I also moved my shop to a bigger facility

between tours.

How does it feel leaving your business to

go on tour?

I hate going out. I get nervous about traveling

at the beginning of every tour. “What

did I forget? What didn’t I bring? What am

I gonna need that I’m not gonna have?”

That sort of thing. I have two of everything

and one stays packed. Once we’ve played a

show and I know I didn’t forget anything,

or I know what I forgot, then I’m okay.

How have your designs changed over the

past 40 years?

Well, like everyone I started out in the early

’70s just copying. The first amps I built for

sale were based on Fender 4x10 Bassmans,

and gradually I just started developing my

own circuits. Now I’m not copying anything.

What products are you currently offering?

The only thing in production right now is

the Little Kahuna, which is a reverberation

and tremolo unit that’s all tube. I still do

custom amps—one-offs and stuff. I can

really only put one thing in production

at a time. So I’ll do a run of a hundred of

something and then do a run of a hundred

of something else. I manage to make

enough to at least always have a couple of

amps in stock and some packed and ready

to go.

The Kahuna came out in 2009?

Kind of. We did the NAMM show in 2009

and showed it. I got started actually building

them at the beginning of 2010, but

then I had cancer surgery so I think I only

got 10 of them shipped before the surgery.

It was out of circulation for a few months

before I came back. Most of them have

been built since late 2010.

How many have you done?

Serial numbers are up to about 70.

And how did you come up with the design?

Well there was a Big Kahuna that was fancier.

It was too much trouble; I only made

a couple of those. But that’s why it’s called

the Little Kahuna. One day I got a sales flyer

from a tube supplier and they had reissued

6BM8s. I thought, “Gee, that’d make a good

reverb,” and I started tinkering with that and

the tremolo. There wasn’t anything like it on

the market. There were some cheesy tremolo

pedals and some bad reverb units, but there

wasn’t a good one in a single box.

Are you making them by yourself?

I have a company that’s making the raw

cabinets for the Kahunas now, but other

than that it’s all me, and I still have to finish

the cabinets myself.

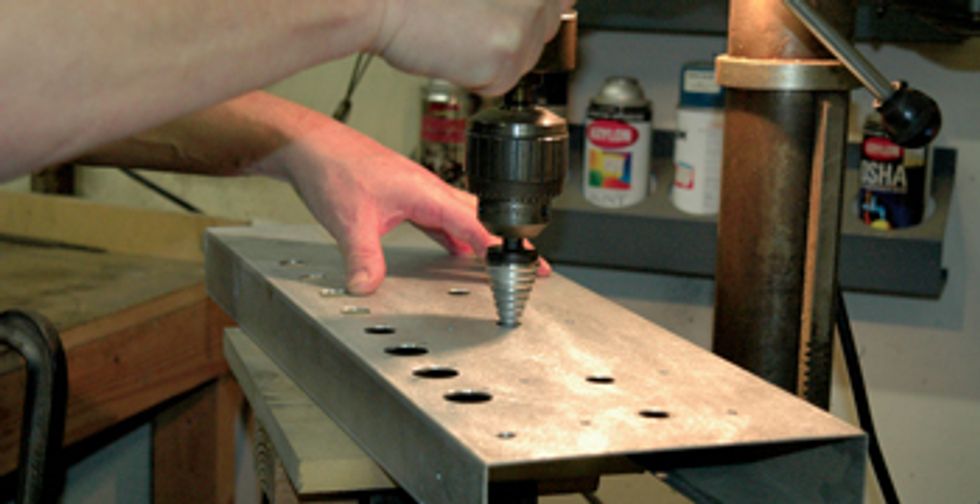

Zoom builds all of his amps by hand in his California workshop. Here he’s shown drilling holes in an amp chassis.

Do you use one when you play?

Yeah, not with X though—X just plays loud.

The room is my reverberation. When I play

rockabilly I use it, and when I do studio

work I always bring it. They’re small, they’re

light, they’re built like a tank—very durable.

Tell us about some of your clients.

I did all of Brian Setzer’s stuff for 18 years

until he moved to Minneapolis. And the guys

from the Black Crowes shoot me stuff. I’ve

worked with No Doubt, Jim Lauderdale,

Blind Lemon, Mike Ness, and I used to [build

stuff for] Dennis Danell when he was in Social

Distortion. I’ve done stuff for Jackson Browne,

Richard Gere, Bruce Willis, all kinds of people.

I was in Hollywood for 25 years.

I didn’t know Bruce Willis played guitar.

Bruce Willis had a band, he played harmonica,

and they used to tour around

Hollywood all the time. He had a bunch of

Fender tweed amps I used to fix, and I fixed

one of his harmonica mics.

Would you say the majority of your clients

are prominent musicians or do you

get amateur players as well?

Since I moved to Orange County I get a

mix. I still get people from all over the country—all over the world now—but it’s a mix.

So you work one-on-one with every client?

Yes.

How do you work with them to come

up with something that you can both be

proud of?

Well, sometimes they know what they want,

and sometimes they just want something. I

talk to them about what style they play and

who they like, what sound they like, what

records they like, where they play, and what

kind of situation they’re going to use it in.

And how long does it usually take to

complete one project?

To do a one-off? Probably 4 to 8 weeks—it

depends how complicated it is. Usually it

depends on how complicated the cabinetry

is, that takes the most time. The Cowboy

amp prototype I did for Gretsch took a lot

of time because of the wraparound grille

and all the asymmetrical parts.

And how did you get hooked up with

Gretsch in the first place? Was it just

because you played one of their guitars?

Yeah, well, because I was so strongly identified

with that one model, the Silver Jet, which

was a really unique guitar. They reissued them

so they don’t seem that unusual anymore,

but back in the ’70s and ’80s mine was the

only one people had ever seen and they

assumed that it was custom. The actual guitar

became sort of an icon. When Fender got

involved with Gretsch, [product manager] Joe

Carducci called me up and we started working

on the Billy Zoom tribute model.

When did you first start working on it?

I think 2007 was when they finally

started doing it seriously. I went out to the

Custom Shop a few times, and we took my

old ’55 Gretsch to a Kaiser Medical Center

to have it X-rayed and stuff, and they stuck

little mirrors up inside of it and measured

things, and then they made a couple prototypes.

They sent me a prototype, then they

made a couple changes to it, and put it

into production.

So do you use one of the new ones or do

you use your original?

I tour usually with the first prototype.

I actually kind of like it. As I go to South

America and Europe, when I have to fly,

I usually take the standard production

model. The prototype is a one-off.

I don’t like to take one-of-a-kind things

on airplanes.

Then why was the original prototype

changed if you like it enough to tour

with it?

They over-relic’d the top on the first one.

The real ones don’t ever show wear on top.

I think they must have gotten that coating

from NASA.

Zoom uses this Tektronix Model 570 to match tubes and compare modern valves to their original specs. “It’s an extremely rare piece,” he says. “Mine came from an electronics school in Minnesota.”

Are you still using the amp you made for

yourself in the ’80s?

Yep. Same amp since ’84. Never a problem.

I changed the tubes once in 2005. My plan

was to make an amp that didn’t break on

tour. It has two 4x12 cabinets and I’ve got

two output sections. I’ve got four 6L6s in

it and you switch back and forth, so in the

event that one ever fails you just switch to

the other output section.

How do you start a project like that?

I started it the way I start every project. I

sit down with a piece of graph paper and

a pencil, and I just kind of stare off into

space and start thinking about circuits.

Then I play with it until it looks right,

and then I go to the shop and I build

what I drew.

What are you doing right now?

Right now I’m looking at a prototype I

made for Gretsch that so far hasn’t made

it into production. It’s a Cowboy amp.

I took the essence of the cowboy-style

amp [that was popular in] the ’50s and

early ’60s and put it on a modern amp.

It’s got the tooled leather binding and

wraparound grille with the steer head on

it and has the reverb and tremolo circuits

from the Kahuna built into it. It’s got

a modified Baxendale EQ and a single

12—it’s 20 watts.

There’s another one that I designed for Gretsch which has active EQ with just a volume control and a single tone control, but the tone control is a two-legged LC circuit, so when you turn the knob, it moves the boost frequency up or down, which gives it a fantastic range of tonal quality. It’s 18 watts with a single 12. And then I’ve got a little 4-watt studio amp, it’s really good for recording. It has gain, master, treble, and bass controls. It’s been very popular with session musicians and studio owners. I can also add a secondary design called a multiwatt to any tube amp—there’s a switch on the back that will vary the actual wattage. I came up with that about 25 years ago. I’ve done probably hundreds of them—it’s a very popular mod.

Have you noticed any trends lately in

terms of what amps players are using?

A lot of people just want something

small that they can play at home—something

they can play in the living room

without deafening everybody.

Are you still innovating with different

mods?

Oh yeah. I’m just building on a new

one now. It’s nothing fancy, just a mod a

guy’s been asking for.

What was he looking for?

I don’t think he knew, so I just made

something I thought he’d like. My goal was to make it sound full and punchy without

having to put any holes in it because

it’s a mid-’60s Bandmaster. I didn’t want

to do anything that couldn’t be removed

completely in about 20 minutes. I wanted

to make an extra gain stage without making

any holes.

What’s special about your designs?

They sound fantastic. They’re almost

unbreakable. One of the ways I like to

challenge myself is using fewer parts than

anybody else uses and making something

that works better. It’s all my own design,

they all have unique circuits, they’re not

really like anything else. They all have

their own unique sounds, and they’re all

different.

How has West Coast culture influenced

your career and ambitions?

I’ve been out here since the ’60s. I don’t

really know what it’s like to live anywhere

else. I like the West Coast. We’ve got mountains and oceans, winding roads

for sports cars, and anything I want I can

get—I can buy, or have it made, within six

blocks of my shop. My shop is kind of like

having my own amusement park. I’ve got

everything I like. My electronics shop has an

amazing assortment of esoteric test gear. I’ve

got two Tektronix tube curve tracers, and

all kinds of laboratory instrumentation, and

then in the back I have a full metal shop so

I can do machining or sheet metal work,

and next to that I have a full wood shop so

I can build cabinets in the back. I also have

a restoration shop, and on the other side of

the wall I have a state-of-the-art recording

studio and a tracking room there. Of course,

it’s all soundproof—it’s a good place to try

out things. If someone wants to try out an

amp, they can go in there and they won’t

bother anybody. I probably wouldn’t leave if

I didn’t have kids.

How old are your kids?

I have 6-year-old twins. A boy and a girl.

Are they going to be musicians?

Gosh, I hope not. I would hope I raised

them better than that. Sometimes they take

instruments from the studio that they want

to play with, but they’re just getting to the

point where they won’t break it faster than I

can tell them not to.

But you have a repair shop.

Yes. I’m still doing repair when I can.

This year it’s been hard for people to

catch me since I’ve been out touring so

much. I closed for a couple months to

move the shop into a bigger unit. It was

just this big, empty, dirty space and we

had to tear a couple walls down, clean the

whole place out, paint it, and do a couple

of walls … so I’ve been kind of hard to

catch. Hopefully I’ll be able to do more

this year.

How do people generally hear about

your business?

I think word of mouth. I’ve been doing it

for so long on the West Coast that pretty

much everyone knows who I am—plus

I’m the guy from X. I’m often out on tour,

which is the only problem, as far as them

getting hold of me.

So does being Billy Zoom help or hinder

your business in the end?

I’m not sure it does either. I was doing it a

long time before there was X. And, then I

was Billy Zoom, but I don’t think it carried

much weight. It’s worked out well for me.

Many people have called you an icon.

How do you relate to that?

I think it’s great. They could call me a lot

worse things. I’ll accept it.

What’s on the immediate horizon for

your amp shop?

I’m still kind of putting things away from

after the move. I’ll be around more in the

coming year than I have been. People can

come into the shop. In the tracking room

of my studio I usually have the Cowboy,

the blue one, the little 4-watt one, and my

X amp, and my old Bassman head has a

bunch of my mods on it so people can try

it and see what I can do.

In the Shop with Mr. Zoom

The time that Billy Zoom puts into handwiring designs he says are “almost unbreakable” is what requires him to make gear in limited-production runs. As he works on custom builds and repairs in his shop, Zoom keeps his original amps with signature mods (including the wattage-varying “multiwatt” mod he came up with 25 years ago) on hand to show customers what he can do. Here’s a look at three of his main creations.

Little Kahuna

The Little Kahuna is an all-tube,

high-end reverb and tremolo

housed in one unit. These

tone machines use one 6BM8

tube and two 12AX7s, with

dual footswitching for silent

movement between effects.

The cabinets are dovetailed

7-ply Baltic birch covered in

heavy NubTex that’s available

in blonde, black, brown, or

tweed. This is Zoom’s only current

model in serial-numbered

production, with the number

made around 70.

Cowboy Amp

Zoom’s 20-watt Cowboy amp

was built originally as a prototype

for Gretsch. He plans to

start production of this amp

and his “Little Blue Killer” (see

below) later this year, starting

with runs of 50 amps per

model. This design has the essence

of cowboy-style amps

from the ’50s and early ’60s,

including tooled-leather binding,

wraparound grille, and a

steer-head logo. It also has

the reverb and tremolo circuits

from the Little Kahuna, as well

as a modified Baxendale EQ.

The Little Blue Killer

This 18-watt amp (also

designed for Gretsch) uses

EL84 power tubes and has

just a volume control and a

single, active tone control.

“When you turn the knob, it

moves the boost frequency

up or down, which gives it a

fantastic range,” Zoom says.

Photos by John Gilhooley