Year after year, we hear from our eclectic audience of stompers with diverse tonal ideas and different things to say. For many of you, true joy comes from putting together your personalized toolbox. For example, one of our readers has an entire Moog pedalboard. A player from Wales uses seven loops and sets them up to conjure the intricate techniques of Paul Gilbert, John Petrucci, and Devin Townsend. One guitarist only uses three pedals but has double that on his board, and yet another decided to take his dirt boxes from the stage into the studio to work on film scores. Read on to get inspired. Perhaps you'll discover something you've never seen done, or get an idea for your ultimate board.

Andrew Phillips: Wailing in Wales

I live in Wales, U.K. This pedalboard has been an ongoing project for the last few years, but I think it’s finally finished … for now! All the pedals are routed into a QuarterMaster QMX 10, made by TheGigRig. This receives the output from the guitar. The rest goes something like this:

Loop 1: TC Electronic PolyTune that acts as a mute.

Loop 2: MXR EVH90 Phase 90 and Petrucci Cry Baby Wah.

Loop 3: TC Electronic HyperGravity Compressor and TC Electronic Petrucci The Dreamscape for clean Dream Theater tones.

Loop 4: Boss SD-1 into KHDK Ghoul Screamer.

Loop 5: Boss SD-1 into Friedman BE-OD (sometimes substituted for Mesa/Boogie Grid Slammer and soon to be Horizon Devices Precision Drive). Loop 4 is used with high-gain amp settings while Loop 5 is used to boost lower-gain amp settings.

Loop 6: DigiTech Whammy and Eventide PitchFactor (with Ernie Ball expression pedal) for Steve Stevens’ ray gun sounds.

Loop 7: MXR EVH117 Flanger.

I have three loops left for future purchases. The QuarterMaster goes out into a Decimator Pro Rack G, which goes to a Mesa/Boogie TriAxis preamp, controlled by a Behringer FCB1010 MIDI Foot Controller.

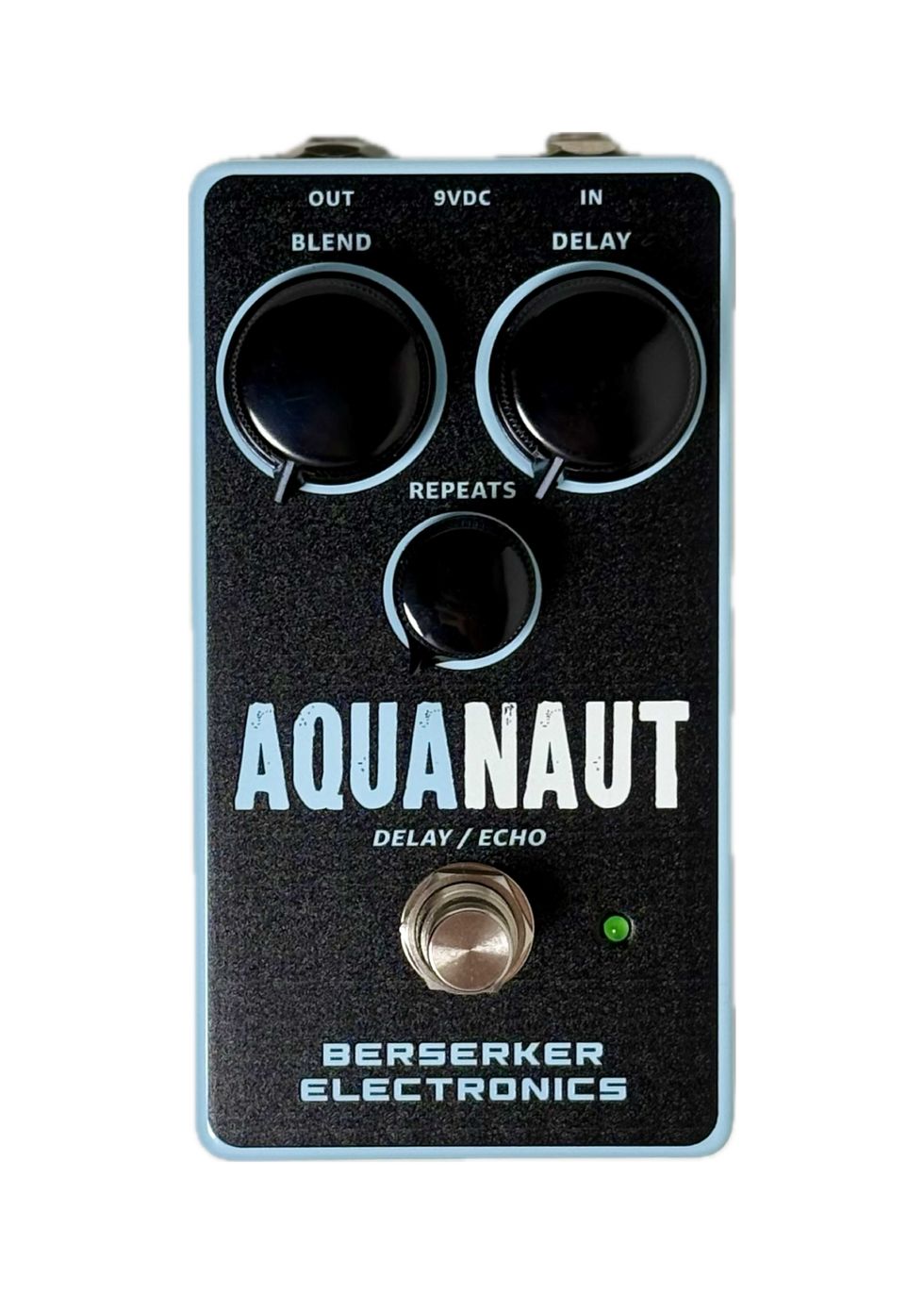

The effects loop of the TriAxis goes to a Mesa/Boogie Five-Band Graphic EQ, then to the MXR Stereo Chorus. My signal then goes to three TC Electronic pedals: a Flashback set for single repeats for the Paul Gilbert “Echo Song” effect, another Flashback set on a Petrucci “Mountain Top” lead setting, and a Hall of Fame Reverb pedal, which goes into the final Flashback set on a ping-pong. This way I can stack delays and even introduce the reverb for Devin Townsend effects. Then it goes back into the TriAxis and is amplified by either a Matrix GT1000FX or Marshall EL84 20/20 through two Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 2x12 cabs. It’s all on a Pedaltrain PRO pedalboard, juiced up by two Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus power supplies.

Bill Raven: Bright Switchin’, Whiskey Burnin’

I’m a guitarist for a country-rock group from La Crosse, Wisconsin, called Burnin’ Whiskey Band. I have a versatile setup that allows me to cover a lot of bases and sounds. I use two blue paisley Blackbird pedalboards. The beginning of my chain is a Line 6 Relay G10, Boss TU-3W Waza Craft, and MXR Reverb on the small board. Then I jump to a Cry Baby Wah, MXR Dyna Comp, MXR Phase 90, MXR Uni-Vibe, Xotic EP Booster, Maxon Envelope Filter, Malekko Sloika, MXR Distortion III, Malekko Helium, Xotic EP Booster with bright switch, Analog Man Prince of Tone, MXR GT-OD, Way Huge Echo-Puss, Strymon DIG, Line 6 M9 (for different tremolo), and a Fender A/B switch (A goes to normal channel on a Fender Deluxe Reverb, B to vibrato channel). This way I can use the amp reverb/tremolo and get a brighter sound on B, and pedal distortion on A, because the “normal” channel on a Deluxe Reverb doesn’t have the bright cap like the vibrato channel. Also, the reason I use two EP Boosters is one is set for my Telecaster and the other, with a bright switch, is set for a Stratocaster.

BJ Beyers: Cosmic Oddities

This setup provides an amazing amount of flexibility, because it can easily nail any tone, from pristine cleans to cosmic oddities to crushing distortions. I’ve made an effort to buy or build what I consider top-class pedals for each effect category, and ended up with an oversized board full of inspiring tones.

My signal chain is as follows: Dunlop Cry Baby Classic Fasel Inductor Wah, handbuilt BYOC 5-knob compressor, Boss DS-1 Distortion (Keeley mod), Analog Man King of Tone overdrive, handbuilt BYOC Ram’s Head Big Muff fuzz clone, an all-white Moogerfooger MIDI MuRF, EarthQuaker Devices Sea Machine chorus, Way Huge Supa-Puss delay, Neunaber Slate reverb with EXP expression pedal, TC Electronic Ditto Looper, a handbuilt BYOC A/B/Y splitter than runs into independent channels of my Vox amp, and a Vox controller that toggles spring reverb and a tremolo.

Chris Roman: Downsized Dirt

I moved from playing live to being a studio player focused on film scores, so I downsized my dirt boxes and started collecting ones that produced different sounds that could be manipulated. I run a compressor and noise gate first, and then I split my signal into two amps: one clean, one dirty. I have a healthy selection of amps in my studio, but my go-to amps are a Matchless Avalon 30 for the clean and a Matchless Excalibur 30 for dirt. Here’s my chain:

• Front end: TC Electronic PolyTune Mini, Keeley 4 Knob Compressor (limited gold top finish), ISP Decimator, Radial Bones Twin City AB/Y Box.

• Clean amp: Electro-Harmonix POG2, Coppersound Effects Telegraph Stutter, Electro-Harmonix Mel9 Tape Replay Machine, JHS Colour Box, MXR Script Phase 90 reissue, Empress Effects Vintage Modified Superdelay, Empress Effects Reverb.

• Dirty amp: Matchless Hot Box III, MJM Effects Brit Bender, Devi Ever FX Bit: Legend of Fuzz, Ibanez TS9B Bass Tube Screamer.

The pedalboards are custom-made by Blackbird Pedalboards, and I use a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 for power.

Fernando Greene: Mean Mooging

This board comes out of many years of being picky and exact in my wants and needs with effects. I handbuilt the Moog board myself. The switching is on a Pedaltrain Grande frame and it’s all powered by TheGigRig. After typing this out, it was more than I expected. Ha-ha—I have a gear problem!

Main board: Strymon Deco, Strymon El Capistan, Pete Cornish ST-2, Cali76, Roger Mayer Voodoo Vibe, Mission Engineering Expressionator, TheGigRig Bank Up Switch, Analog Man Surface, Peterson Strobe Stomp, TheGigRig WetBox, JHS Colour Box, Rockett Treble Boost, Rockett Afterburner, Sustain Punch Creamy Dreamer, GTC Bloody Finger, Mission Engineering Expression Pedal, RMC10 wah, Mission Engineering VM-1, Chicago Iron Octavia, TheGigRig G2, and an Eventide Space.

All-Moog board: CP-251 (connected and used with Phaser), MF-104SD, MF-105 MIDI MuRF, MF-105B Bass MuRF, MF-108M, MF-101 Lowpass Filter, MF-102 Ring Modulator, MF-103 12-Stage Phaser, MF-107 FreqBox, three Expression Pedals (to control a MF-104SD), and a MP-201 Multi-Pedal (controls Lowpass Filter, Ring Modulator, 12-Stage Phaser, FreqBox).

Joe Giordano: Illinoise

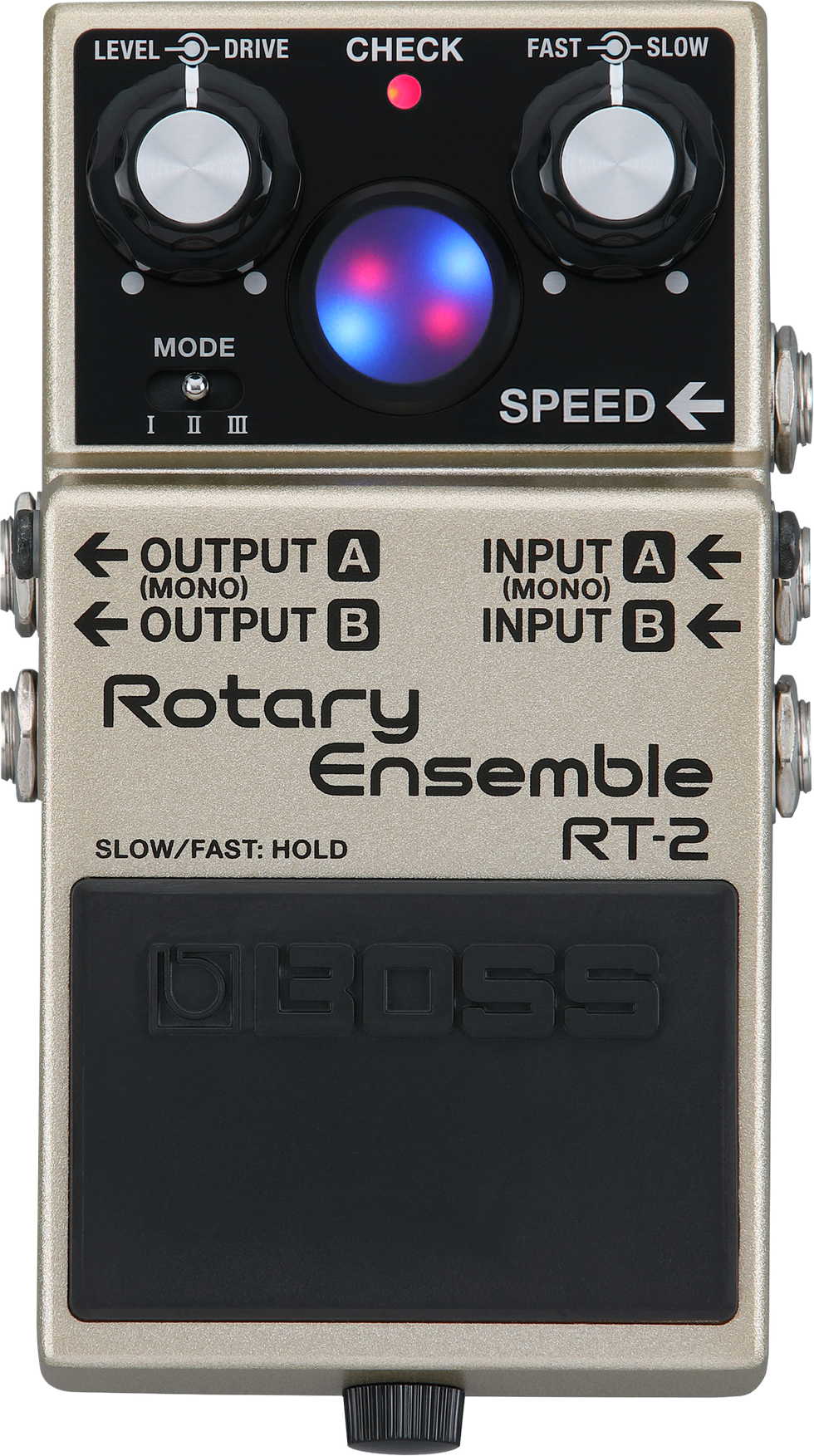

I live just outside of Chicago, Illinois, where I play with a band called Dig Engine. I love Premier Guitar! Here’s my pedalboard: Sarno Steel Guitar Black Box (not pictured), Neo Ventilator II (Leslie speaker simulator), Dunlop GCB95 Cry Baby Wah, two Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamers (silver modification done by Analog Man), Analog Man Comprossor, Electro-Harmonix Micro POG, BBE Tremor Tremolo, DigiTech Whammy II, Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler (mod by Alchemy Audio), Keeley Katana Clean Boost, Boomerang III Phrase Sampler. All pedals are powered by a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power Mondo (isolated power).

Martin Cheney: Old Faithful

Here’s my main board. Some of the pedals are more than 20 years old, including an original Pedal Power. The top level is on hinges, which allows me to access the NS-2 and power cords. The outlet on the Pedal Power allows me to plug in the adaptors for the DigiTech Whammy and TC Electronic RPT-1 Nova Repeater.

The Boss TU-2 and NS-2 have the “power out” option. The NS-2 powers the Boss GE-7 EQ and the TU-2 powers the Xotic SP Compressor and wah. At the moment, I’m using a Moen Jimi Zero Vibe as my modulation, but I have another board almost identical to this (without the volume pedal and whammy), which has a Boss flanger and phaser so I can swap those in and out.

A few years back I was trying to figure out how to make my tone better without buying new pedals, so I bought mod kits from Monte Allums and they turned our great—with thanks to some help from my dad, who is great with electronics. We also did the true-bypass mod on both of my wah pedals.

I just measured it out and bought the wood from a hardware store and spray-painted it flat black.

This is my chain: Ernie Ball Volume, Boss TU-2 Tuner, DigiTech Whammy, Dunlop Cry Baby Wah (true-bypass + vocal mod; a small knob on the side can adjust one of the internal resistors), and Boss Noise Suppressor.

• Loop Send: Xotic SP Compressor, Moen UL-VB Jimi Zero Vibe, Boss Metal Zone (Monte Allums mod), Boss Blues Driver (Monte Allums mod), and Boss Distortion (Keeley mod).

• Loop Return: Boss Tremolo (Monte Allums mod), TC Electronic RPT-1 Nova Repeater, DOD DFX9 Digital Delay, and Boss GE-7 EQ (Monte Allums mod).

Matt Beatty: Mini to Main

There’s nothing really special about my board, but what I pride myself in is that I welded it myself with scrap metal from work, so it cost me nothing. The expanded metal allows for cables to be run above or below the board and makes for one sturdy, rugged board.

My mini-board started when my girlfriend began buying the Ibanez mini series pedals for me, just for her love of “all things mini.” I then welded a “mini” board to house these awesome tiny creations, which so far include an Ibanez Tube Screamer Mini, Ibanez Super Metal Mini, MXR Phase 95, and Ibanez Analog Delay mini. Soon enough, my mini board may become my main board. Cheers from Canada!

Mike Simpson: Overdrive Champion

I play in an ’80s and ’90s dance band and a ’70s hard-rock band, so I needed a board that would handle everything for both types of music. The real champ of the board is the Friedman BE-OD. It’s the best distortion pedal I’ve ever used.

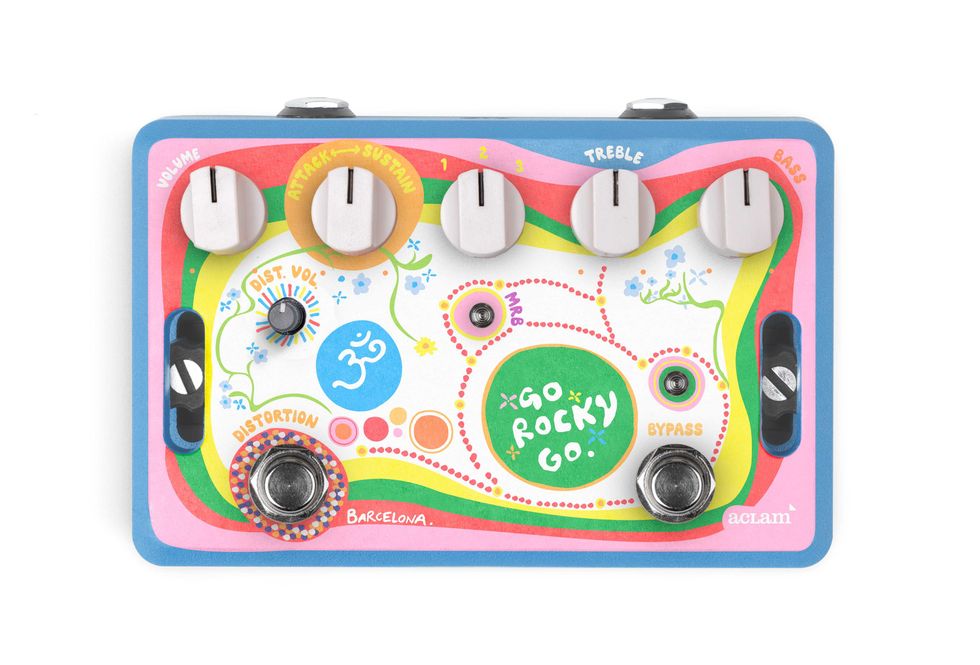

My pedalboard consists of the following: Chemistry Design Werks Holyboard (painted by my kids), Morley Bad Horsie 2, Electro-Harmonix POG2, Line 6 M9 Stompbox Modeler, MXR EVH90 Phase 90, DigiTech Bad Monkey, DigiTech Whammy 5, Friedman BE-OD, two Dunlop Volume X Mini pedals (one for volume, one for expression for the Line 6 M9), and a Big Joe Power Box.

Mike Svensson: Three Pedals and the Truth

Hi from Sweden! My board is straightforward and houses very few things. I’ve had basically the same pedal setup for the last 15 years. All pedals go through the effects loop of my amp in this order: Boss TU-3 tuner (only used as a mute when swapping between guitars), Dunlop Cry Baby Wah, original DigiTech Whammy WH-1 (I have five of these), two Boss DD-3 delays (I could get by with one, but live it’s easier not changing settings too much), a DOD FX40B Equalizer (set flat and only used as a boost for solos), and finally the MXR Phase 90 (which I don’t really use).

I only use three pedals frequently: wah, Whammy, one DD-3. The EQ isn’t really an “effect.” I recently tried to use a Keeley Mini Katana Clean Boost in place of the EQ, but I changed back. I’m a creature of habit, and while the Katana served well, it wasn’t the same. I’ve tried every Whammy model except for the newest DT and WH-5 models. Nothing comes close to the original, both in terms of sound and ease of use. My current wah is a new unit, but my favorite is an ’80s model which sounds much better than any other Cry Baby I’ve tried. I keep that on my backup board (identical to this one, except it houses only one delay). The sweep is much cleaner, smoother, and never gets too high. Unfortunately, it isn’t very reliable to use live, but I always record with it.

Nathan Hall: Tidy Tone

Hi Premier Guitar! My board and I come from Maine. This fairly compact (for me) setup gives me everything I need for playing blues and classic rock at jams and home practice. The Temple Audio board is new to me. I’m loving the departure from Velcro and the tidy system, which enables using mounting plates or zip ties. I use Monster and George L cables, and my signal path is as follows: Real McCoy Custom Picture Wah, TC Electronic PolyTune, Fulltone Supa-Trem, MXR EVH Phase 90, Xotic EP Booster, Xotic AC Booster Comp, Fulltone OCD, Xotic RC Booster V2, TC Electronic Ditto Looper. My wah is powered by a 9V battery; everything else is powered by a Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2, mounted underneath. I usually play a Gibson Les Paul Traditional goldtop into a Marshall DSL50 and 1936 2x12 cab with Celestion Greenbacks.

Roshan Vasudev: The Brain

Here's my baby! I've been playing for years and just couldn't find “my sound" or get organized with all the various combinations of pedals and tones. I was searching for good quality pedals that would make my tone as sweet as Steve Rothery's or Steven Wilson's. I remembered the amazing Rig Rundown video of Steven Wilson's board, and that got me going. I started with a Strymon TimeLine and quickly added the BigSky, then snuck in the Providence when I saw that on one of Guthrie Govan's boards. I also came across That Pedal Show, which sucked me in entirely (hours of videos and reviews to sink my ears into)!

I also started to search for a “brain" to help calm the “pedalboard tap dance," and thanks to PG reviews and an amazing video by Pete Thorn on the RJM Mastermind, I was immediately hooked! So, I decided to abandon all those old cheap pedals and embark on a much more rewarding (and wallet-emptying) endeavor.

Here are the pieces that make this board sing: Electro-Harmonix Nano POG, Xotic SP Compressor, Xotic EP Booster, Boss BD-2 Blues Driver, Thorpy FX Muffroom Cloud (Fallout Cloud), TC-Helicon VoiceTone Harmony-G XT, Providence Anadime Chorus, Pigtronix Rototron, Strymon TimeLine, Strymon BigSky, Lehle Mono Volume Pedal, and Roland EV-5 Expression Pedal.

They're all controlled by “the brain"—RJM Music's Mastermind PBC.

Wesley Farmer: Pedal Dancer

At first glance, this pedalboard might look complicated, but it’s not too complex compared to other boards I’ve seen. I wanted a board that could get me pretty much any tone for the different styles of music I play the most (alternative, classic rock, blues, Americana, prog, and ambient), and the pedals had to be easy to use while still being quality. I made sure no pedal had more than four to five knobs, to keep things as simple as possible.

Here’s the signal path: Boss FV-500H Volume Pedal, DigiTech Whammy (4th gen), Dunlop Cry Baby Wah, Electro-Harmonix Micro POG, Electro-Harmonix Soul Preacher Compressor/Sustainer, MXR Phase 90, Ibanez TS808 Tube Screamer, JHS Angry Charlie V3, Vox Satchurator, Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi, TC Electronic PolyTune 2, Boss CH-1 Super Chorus, MXR Micro Flanger, Boss TR-2 Tremolo, Boss DD-7 Digital Delay (with Quik Lok PS-10 pedal for tap tempo), TC Electronic Shaker Vibrato, Strymon Lex Rotary, TC Electronic Flashback Delay, Boss RV-6 Reverb, TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb, and a JHS Little Black Buffer (under the board). Also pictured is the footswitch to a Fender ’65 Princeton Reverb Reissue.

Pedals are on the Pedaltrain Classic Pro, patch cables are all from Hosa, and the board is powered by the Truetone 1 Spot Pro CS12. My board was built by Jordan McCown at Mountain Music Exchange in Pikeville, Kentucky. He does great work! Time to do the pedal dance…

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.