I confess: I don’t like MIDI guitar. Or I didn’t. I guess what I don’t actually like is the accepted notion of MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) guitar, which is to turn our beloved 6-string into a controller to trigger cheesy synth sounds like pan flute, digital piano, or sampled sax. When you factor in tracking delays (the lag time between plucking a note on a guitar string and when a synth sound actually comes out of a speaker), note misfires, extra cables, special pickups, interfaces, extra floor pedals, and patching into a PA, the sonic promise of MIDI guitar seems musically questionable. In the past, I figured this technology was best left to YouTube noodle-nerds.

But on the other hand, I like effects. I like new sounds. I like trying to push sonic limits, especially since I get bored with stock guitar pretty easily. And though I can kind of get around on the keyboard, I have much greater facility on the guitar. So for sequencing or software-based notation, being able to just play guitar rather than hunt and peck on a keyboard would sure be nice.

After 30 years of MIDI guitar development, most guitarists now stay clear of using the guitar as a controller. Sure, MIDI is commonly used on floor controllers to change patches on multi-effect units or true-bypass pedal loopers, but this is different from using the guitar itself to play a synthesizer or control effect parameters.

We live in an incredible age of music software and synthesis, so it seems well worth taking a fresh look at MIDI guitar, especially in light of new ways to convert guitar notes to MIDI signals. And imagine the rewards if you could make MIDI work: You’d be able to tap into the vast galaxy of software synths and plug-in effects, create unique sounds, and input MIDI signals into sequencing software with ease. Rather than getting frustrated by the inherent quirks of using guitar as a MIDI controller, perhaps one can have a more Zen-like attitude. In this article, we’ll explore a bit of guitar synth history, the current state of MIDI guitar, and ways to take advantage of MIDI while minimizing the guitar-specific pitfalls.

A Brief History of Guitar Synthesizers

The early ’70s saw the introduction of guitar “synthesizers,” which were really analog effect units that created synth-like tones from a guitar pickup’s output while preserving the sound of a normal electric guitar. While these systems occasionally found users, few guitarists adopted them. They were expensive, unwieldy, and sonically limited or disappointing —especially when compared to a keyboard.

True guitar synths started to appear in the late ’70s. Rather than merely processing a guitar signal, these systems analyzed the pitches played on a guitar and then used the resulting information to control synthesizer circuitry. Roland developed a system that was widely adopted. They started with the GS500, followed by improved versions in the form of the GR300 and associated compatible guitars (G303 and G808). These guitar synths were polyphonic, had musically viable sounds, and delivered tracking speed and accuracy that some say has yet to be eclipsed.

By the mid ’80s, MIDI had become established as a way of sending note on/off signals and other musical information from one device to another. Now there was a standardized way to control one synthesizer from a MIDI-compatible keyboard, or, as interest to us here, from a guitar equipped with a hexaphonic pickup and a pitch-to-MIDI conversion system. Roland, Ibanez, Charvel, and a host of other manufacturers offered pitch-to-MIDI conversion systems, with Roland’s GK hexaphonic pickups becoming the standard with their 24-pin (and later 13-pin) connection systems. In 1988, Casio introduced the MG-510 a Strat-style guitar with a built-in hexaphonic pickup, converter, and synth sounds.

Compared to the early Roland guitar synths, these MIDI-based guitar synths had latency issues—the time it takes between when a note is first plucked to when a synth sound is emitted. (For a detailed look at how I measure latency, check out the sidebar.) While keyboards have the advantage of directly triggering a MIDI note, a guitar has a vibrating string that needs to cycle around at least once before it can be recognized by the pitch-to-MIDI system as a musical note. For low notes, it can take over 10 milliseconds (ms) just for a cycle to complete itself, and longer for a note to stabilize and be a recognizable pitch. When combined with the delays inherent in the MIDI synths of the day, tracking delays of well over 50 ms for the guitar’s lowest notes were the rule. This is easily enough time to create a bothersome pause between physical action and hearing a sound.

To get around this tracking delay, a few manufacturers created guitar-like controllers that produced no sound on their own, like the SynthAxe and the Yamaha G10, but provided reduced tracking delays by bypassing the pitch-to-MIDI conversion process. While a few well-known guitarists like Allan Holdsworth and Lee Ritenour employed the SynthAxe, guitar-like controllers never gained traction in the broader guitar marketplace. Instead, the dominant MIDI guitar technology from the early ’90s to today remains a hexaphonic pickup driving a pitch-to-MIDI conversion circuit, sometimes built into a synth unit (like Roland’s series of rack and floor guitar synths, such as the currently produced GR-55).

In the last few years, there have been two notable advances in polyphonic MIDI guitar technology. The first is the Fishman TriplePlay guitar pickup, which transmits MIDI data wirelessly to a USB dongle for direct access to software synths and sequencing software. Tracking delays with the TriplePlay are dependent on software settings (sample rate and buffer size), but typical values for the Fishman TriplePlay seem to be comparable or perhaps slightly better than Roland’s current systems.

The second recent advance is Jam Origin’s MIDI Guitar software for computer or iOS devices, which requires no special pickup yet allows for polyphonic MIDI conversion. You connect your guitar to an audio interface, route it through MIDI Guitar, enable a software synth, and route out to a PA or amp. Measured tracking delays with MIDI Guitar software running as a VST plug-in within Ableton Live using a Zoom TAC-2 Thunderbolt audio interface set to a 44.1 kHz sample rate with a buffer setting of 64 samples, fell between about 30 ms for low notes and 20 ms for high notes.

While not perfect, these two systems offer a convenient—and thus very appealing—way to tap into the unlimited palettes of software synths and computer-based effects.

Setup

If you want to have a MIDI guitar setup that works in live situations, the first thing to consider is whether you want synth sounds to go to your amp or a PA. With a unit like the Roland GR-55 (which requires a divided pickup similar to the Roland GK-3), separate outputs are available for synth and guitar sounds. You can also route your standard, non-processed guitar signal to the synth outputs and send a blend of both signals to an amp or a PA.

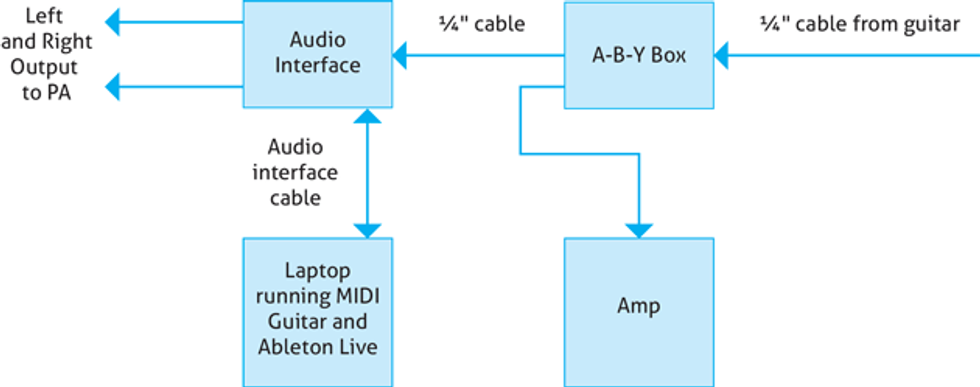

With a laptop or tablet-based MIDI guitar synth setup, things can get a little more complicated. Fig. 1 is a diagram of one way to set things up.

Fig. 1

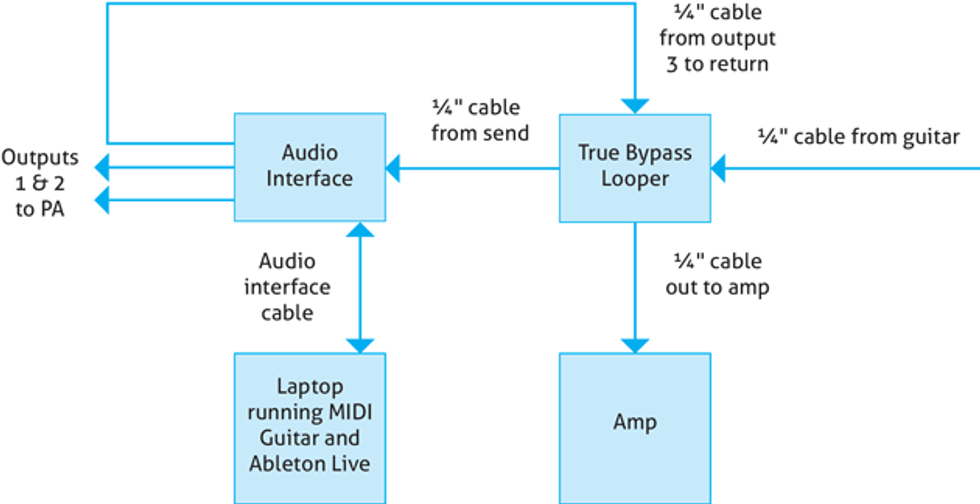

The limitation of the setup in Fig. 1 is that you can’t route computer-based effects or synth sounds to your amp. Fig. 2 shows an alternative setup that will route laptop-based synth sounds or processed guitar to your amp.

Fig. 2

With this second setup, the laptop essentially becomes an effects unit placed in a true bypass loop. It’s easy to switch the laptop in and out by simply hitting one button. With this approach, you need at least three separate output channels on your interface, or if you’re using a Mac, you can create an aggregate device in the Audio MIDI Setup utility to combine the interface and built-in outputs. With an aggregate device, you can run the Mac’s stereo outs to a PA system and your guitar from a mono output on your interface back into the true bypass looper. You select the channels on which to route guitar or synth sounds via software.

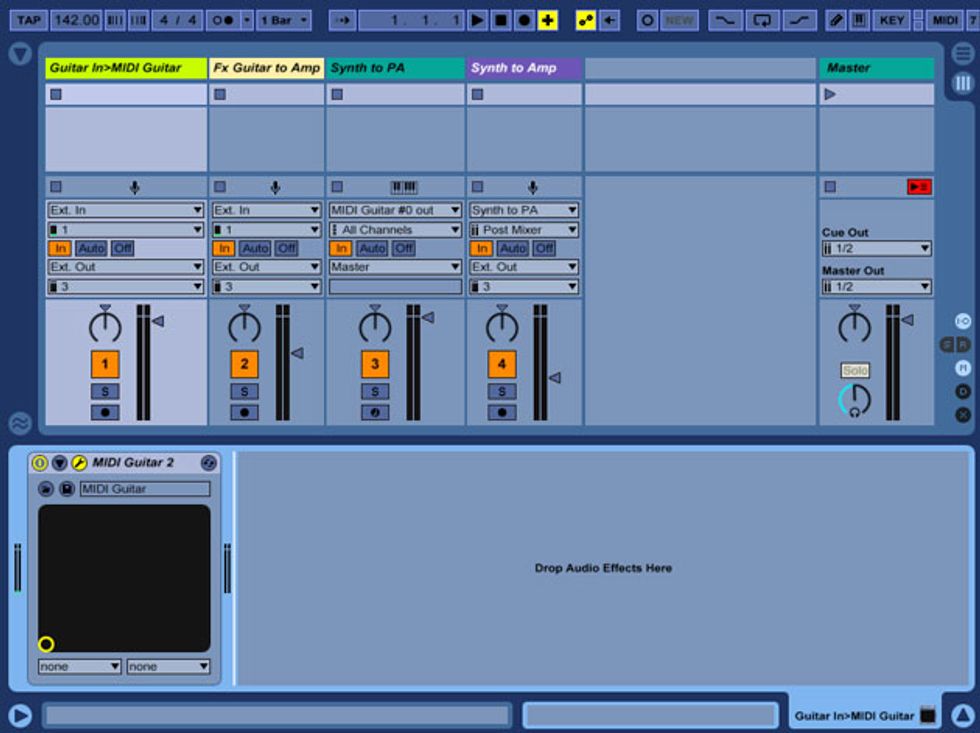

Fig. 3

Take a look at Fig. 3 to see how I’d set this up in Ableton Live. This screen shot shows Ableton Live running Jam Origin’s MIDI Guitar as a plug-in in the configuration illustrated in Fig. 2. Notice that the 2nd and 4th tracks are routed to output 3 (guitar amp) and the synth is routed to the master output stereo channels 1 and 2 (PA).

Fig. 4 shows my preferred settings in MIDI Guitar when running it as a plug-in in Ableton Live. Note that the buffer is set to 128 samples (upper left region), which typically provides very good low-latency performance, particularly with a Thunderbolt audio interface such as a Zoom TAC-2.

Fig. 4

All the following audio examples use MIDI Guitar, because I like being able to play any of my electric guitars with MIDI without having a special pickup or pitch-to-MIDI interface.

Now What?

Once your guitar is set up as a MIDI controller, it would be easy to open a software synth plug-in and start noodling away, playing all the things one normally plays on guitar. The results could be passable, but often they’re cringe-worthy. Tracking delay (even with the respectable results MIDI Guitar provides) can ruin a groove, the subtleties of muted notes and pick variations are lost, and slides and other guitaristic gestures can sound comical as translated by a synth.

And almost always, you have to play extremely cleanly to not trigger wrong and even out-of-key note blips. This can hamper your fluidity. Of course you can always blend in your guitar, so your musical intention is better captured, but this can lead to a dated, stacked-synth sound. In this realm, more is usually not better. What to do? The universe is infinite, but here are a few starting points to explore:

- Use synth sounds that have a soft attack to minimize the perceived tracking delay.

- Use slicer/chopping plug-ins post-synth to create in-the-pocket rhythms.

- Use MIDI plug-ins like arpeggiators and harmonizers to play things that would be impossible on the guitar.

- Trigger non-musical sounds, like speech snippets or noises.

- Use the guitar as a controller to trigger effects parameters, channel muting, and any other MIDI-controllable parameters that respond to note on/off messages.

The audio examples I’ve included here have two goals: (1) to avoid simply turning the guitar into a bogus keyboard and working within the limitations of using vibrating strings to control MIDI, and (2) to inspire you to think of novel ways to use your guitar with MIDI.

Talk about cheating! In Ex. 1 and Ex. 2, I play single notes and let MIDI Guitar’s built-in arpeggiator function do the hard work. The guitar is panned slightly to the left, with the synths a bit to the right. (To hear the audio examples for this article, go to premierguitar.com.)

After listening to Ex. 3, you might say, “I don’t hear any MIDI guitar in this.” I’ve set up Ableton Live to have three different effects that are turned on or off only by specific notes (E3, A3, and G4). In guitar terms, those refer to the open 6th string, the A at the 5th fret of the 6th string, and G on the 15th fret of the 6th string. Whenever I hit the open E the signal is sent to a panned delay effect.

The effect on the A note is a bit more complicated. It triggers a pre-made MIDI clip in Live that’s a chromatic scale that starts on A and descends. This clip serves as a controller for the QuikQuak’s PitchWheel plug-in, which receives audio from the guitar channel’s send and MIDI from the chromatic MIDI clip. When A is struck, the clip starts (sending MIDI data to PitchWheel) and the send on the guitar input channel jumps from 0 to maximum, which sends audio to PitchWheel. To not have this chromatic pitch effect stay on, I have to hit the note again.

The high G that’s triggered when I hit the E minor chord sends audio from the guitar input to a return channel with Ableton Live’s Grain Delay plug-in with the Bubbles preset. Take a look at Fig. 5 to see the PitchWheel plug-in in action.

Fig. 5

Unfortunately, functions triggered with a MIDI note in Live are not momentary, so normally you would have to hit a note a second time to turn off a mapped parameter (as I did with the A3 triggered clip/effect). But thanks to the Momentary 8 plug-in made by Max for Ableton Live, incoming note messages are transformed from toggle to momentary. Thus, when the note stops, the effect is turned off.

In Ex. 4, I took audio of an auctioneer and matched his voice to a MIDI drum rack in Ableton Live. You can hear my original guitar track on the left side and the resulting triggered audio on the right. This example was inspired by the great drummer Deantoni Parks, who in his latest record, Technoself, samples speech, chops it up, and plays the deconstructed words on a keyboard with his right hand while he plays drums with his left hand. The effect is mesmerizing.

For this example (unlike the others), I slightly time-corrected the entire MIDI auctioneer sample track by 30 ms to roughly compensate for the latency I measured with MIDI Guitar that occurs in the pitch-to-MIDI process. Though it sounded good without the correction, it was just tighter with it.

Here’s another example (Ex. 5) of using specific notes on the guitar to trigger effects. In this case, the effects are all within Izotope’s Stutter Edit. I start by playing F notes, with ascending upper notes (starting on a high D) that will trigger various Stutter Edits presets. Then I play an arpeggiated figure, and finally some funk rhythm stuff. Because MIDI Guitar software is polyphonic, it can recognize notes that are within a chord, so that chords that contain particular notes will also trigger the effect.

Okay, finally an example of pure synth being playing by the guitar. But there would be no way to really play Ex. 6 accurately without the help of rhythm-chopping plug-ins. Frankly, to my ears and from my experience trying, the current state of MIDI guitar is just not good enough to play rhythmically with a synth plug-in, particularly if you hope to capture all the funky note mutings and rhythmic scratches that help make rhythm guitar compelling. Perhaps it can be passable for simple rhythms, but generally, you cannot match what a good keyboard player can do rhythmically.

In Ex. 6, what I played on the guitar is pretty darn simple. I start with a basic single-note line and then go into some chords. But all I’m doing is holding chords for a half-note or full measure—the software is doing all the rest. MIDI Guitar is routed to a TAL Software’s excellent TAL-U-NO-LX synth, and then getting chopped up, gated, delayed, and panned by the super-cool Audio Damage BigSeq2 plug-in (Fig. 6). I could post my dry guitar track, but like the Great Oz, I’d rather just say, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

Fig. 6

In this next example (Ex. 7), I play a melody in D minor and then at the end of the first phrase I hit a high D on the 1st string. This note is mapped to the channel “on” button of a synthesizer track in Ableton Live. Once you hit that note, the track is enabled. The channel has a scale plug-in before the synth set to harmonize all the notes I play up a third, but in the key of D natural minor/F major. I also bend notes here to illustrate MIDI Guitar’s very usable pitch-bend tracking.

Sequencing and Notation

If you are ivory-challenged, using the guitar as a MIDI controller in conjunction with sequencing software or notation software can be a godsend. With sequencing software, latency and tracking delay concerns can be overcome since you can quantize or manually align notes. With most notation software, such as Sibelius or Finale, you can either import a MIDI part, or in some cases play directly into the software. Of course, you have to understand notation because inevitably you’ll need to correct misinterpreted rhythms, simplify confusingly written rhythms, change enharmonic notes to ones that are easier to read, etc. But this isn’t unique to guitar—imported or played MIDI parts almost always require cleanup, regardless of what controller created the parts.

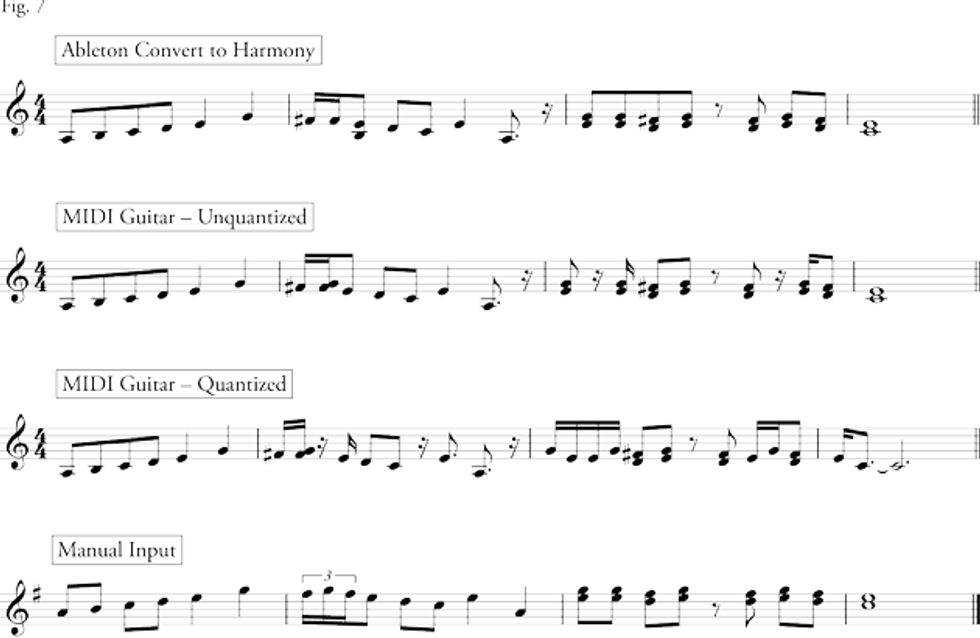

In this notation example (Ex. 8), you can hear the raw guitar track playing a relatively simple melody in A minor. The guitar was converted to MIDI with both MIDI Guitar and Ableton Live’s Convert Harmony to New MIDI Track function. The MIDI Guitar track was also copied and quantized. All three MIDI tracks were exported from Live as MIDI clips and imported into Overture notation software, which in my experience does as good a job at intelligently converting MIDI files to notation as any notation software.

While all three imports are in the ballpark, there are some problems (Fig. 7). First, the key signature was not automatically converted, so you need to know what key the clip is in. Second, the guitar should be written an octave higher than it sounds—standard practice for guitar notation. Third, the triplet in the second measure was not captured properly. And finally, the third measure came out differently in all the three imports, with the Ableton Convert to Harmony being the closest. The last staff shows the phrase more properly and legibly notated, which I did manually. With even simpler lines, however, the chances of accurate MIDI transcription are higher, but you always need to be vigilant that the conversion-to-notation process was done accurately and legibly.

Fig. 7

Using the guitar as a MIDI controller does have its pitfalls, but it can be an excellent creative and useful tool. As I’ve attempted to demonstrate with the examples in this article, you can use your guitar to trigger extra MIDI notes with arpeggiators or harmonizers, trigger effects, and play sounds that don’t have to be “normal” instruments or even synths. You can correct for MIDI tracking delay and overcome groove-busting lags by forcing sounds through synchronized gating effects. An added bonus is that you can use guitar to input MIDI for sequencing and notation, though some cleanup is usually required. Hopefully, these examples get your brain thinking about novel and cool ways to use MIDI with guitar. Surprises await.

Testing Latency

With Jam Origin’s MIDI Guitar 2, I measured overall latency (which includes tracking delay from pitch-to-MIDI conversion) using the following procedure:

- Record a simple one-note-per-string phrase from my guitar into a looper pedal to ensure performance consistency. From low to high, the notes were Bb–Eb–Ab–Db–Gb–B on the 6th and 7th frets.

- Route the looper pedal output to an input of the audio interface.

- Route an output from the audio interface to a miked amp.

- Route the microphone in front of amp speaker to second input on audio interface.

I then setup the following tracks in Ableton Live:

- Guitar input with MIDI Guitar 2 as a plug-in

- Guitar direct input

- MIDI track with keyboard plug-in (preferably using a sound with a sharp attack) receiving MIDI signal from MIDI Guitar 2 plug-in

- Miked amp track

Next, I’d play the looped phrase and simultaneously record direct guitar and miked amp synth signal. Once the parts were recorded, I would zoom in to tracks and measure the distance in milliseconds (ms) between the start of the direct guitar waveform and triggered synth signal.

I repeated the procedure above with various buffer settings, running MIDI Guitar 2 as both a plug-in and standalone app while switching between monophonic and polyphonic modes. With a sample rate of 44.1 kHz and a buffer setting of 64 samples, I measured the following average latencies between the onset of a note with direct guitar and miked synth through an amp while running MIDI Guitar 2 as a plug-in on a channel in Ableton Live:

| Note (low to high, 6th and 7th frets) | Latency (milliseconds) |

|---|---|

| Bb | 38.0 |

| Eb | 35.5 |

| Ab | 30.0 |

| Db | 26.8 |

| Gb | 24.3 |

| B | 21.2 |

I repeated the identical tests in Reaper, another DAW, and it yielded similar results.

Switching between monophonic and polyphonic modes in MIDI Guitar had little effect, though monophonic tended to show 1 to 3 ms less tracking delay. Trying different soft synth plug-ins also had little effect on the measurements, with perhaps a 1 or 2 ms difference between different soft synths. Running MIDI Guitar 2 as a standalone app and inputting MIDI from its virtual MIDI out or IAC Bus had little effect on latency performance, although with my system CPU performance was improved and I could get away with lower buffer sizes while running MIDI Guitar 2 in standalone mode rather than as a plug-in. Interestingly, the difference in measured latency between a 32-sample buffer and a 256-sample buffer in standalone mode was not too dramatic, while the CPU benefits can be very tangible.

Bear in mind these measured latency values include a software offset to make sure that output and recorded audio are in sync. With the test system here—a MacBook Pro i5 2.9 GHz Intel Core i5 with 8 GB of RAM and a Zoom TAC-2 Thunderbolt audio interface running at 44.1 kHz—the software offset needed (as measured in Reaper) is 185 samples, or 4.2 ms. Also, it is worth noting that the recorded MIDI data (the output from MIDI Guitar) was approximately 1/2 to 2/3 the latency of the recorded synth audio and generally under 20 ms. This seems to indicate that MIDI Guitar is remarkably fast at pitch-to-MIDI conversion.