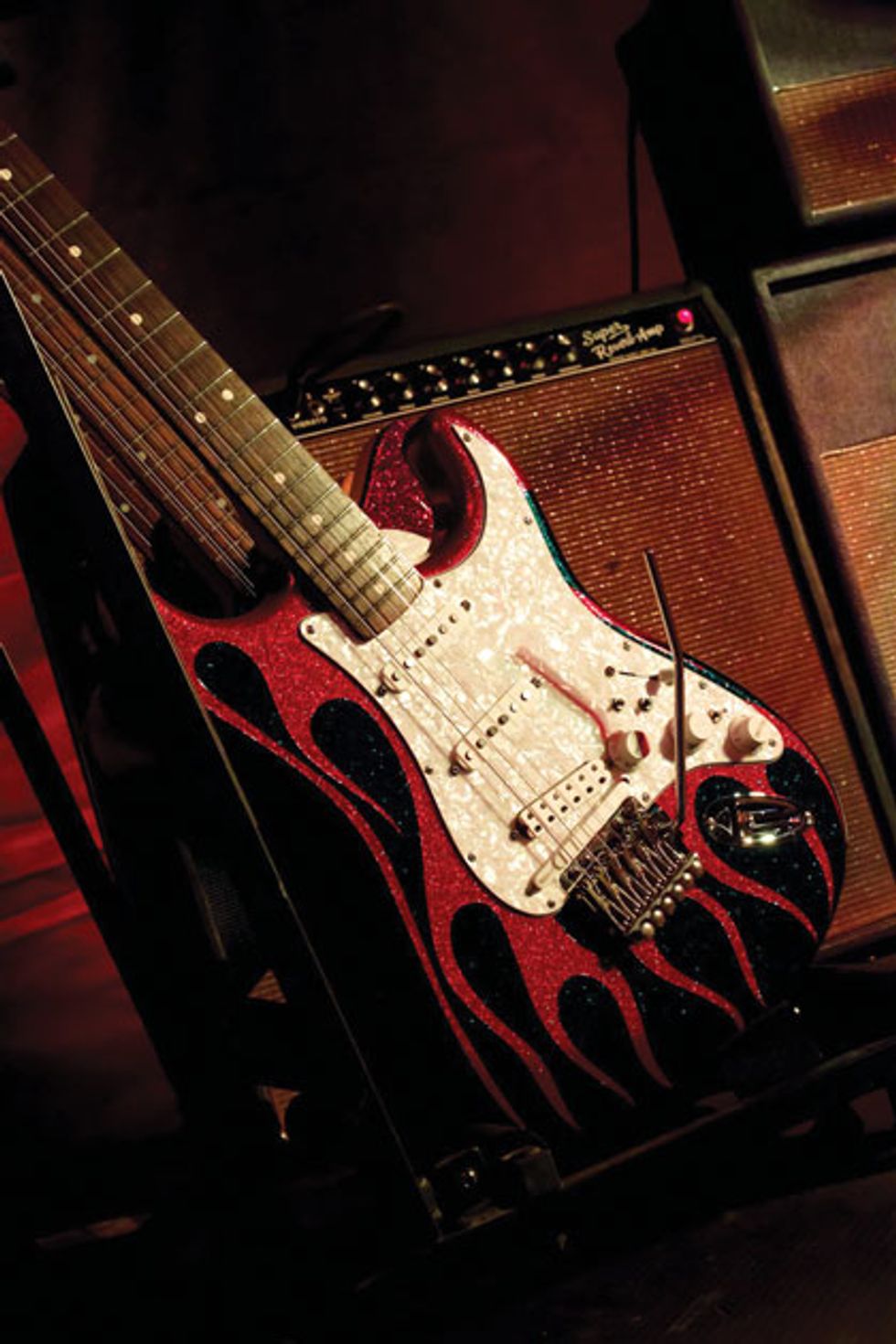

Danny Carr

Danny Carr of San Jose, California, says this sparkle-flamed beauty started out as a 2004 Roland Ready Strat. “Aside from the wood, frets, Roland circuit boards, and hex pickup, there’s not much left that’s original,” notes Carr. The new neck and middle pickups are single-coil GFS Vintage Staggers (neither is reverse-wound), while the bridge is a Duncan Li’l Screamin’ Demon humbucker. The pickguard is from Pickguard Heaven, the pearloid-knob tuners are by Schaller, the locking whammy system is by Super Vee, and Willies Rod and Kustom Car Shop of Campbell, California, provided the glorious paint job.

The electronics are equally ambitious: Switch 1 is a standard 5-way pickup selector. Switch 2 activates the bridge pickup (providing seven possible combinations from the non-synth pickups). Switches 3 and 4 control the synth pickup, and a push/pull tone knob houses a fifth switch to toggle the humbucker between series and parallel mode. “For 16 years I’ve played in a classic-rock cover band, which means I have to cover a ton of sonic territory,” says Carr. “With the mods on this guitar, there’s not much I can’t do.”

Throughout the year we collect stories and photos of guitar-mod projects created by you, our dear readers. Some are so inspiring that we include them here in our annual Hot Rod issue.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)