|

|

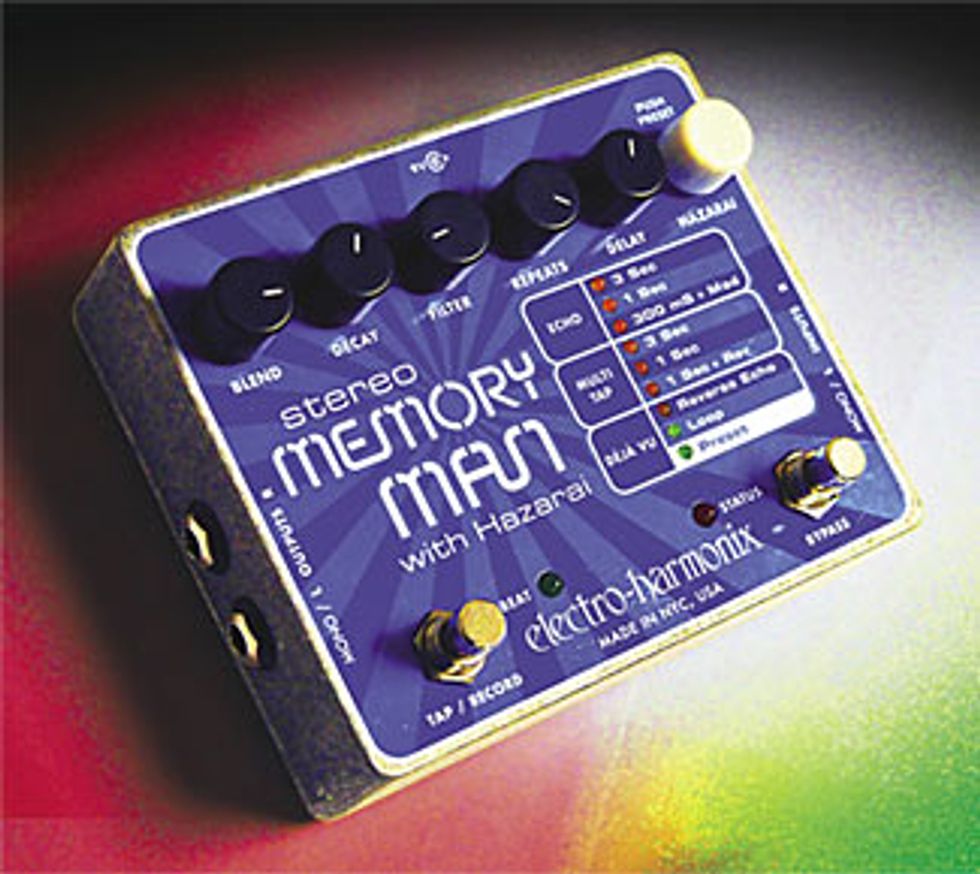

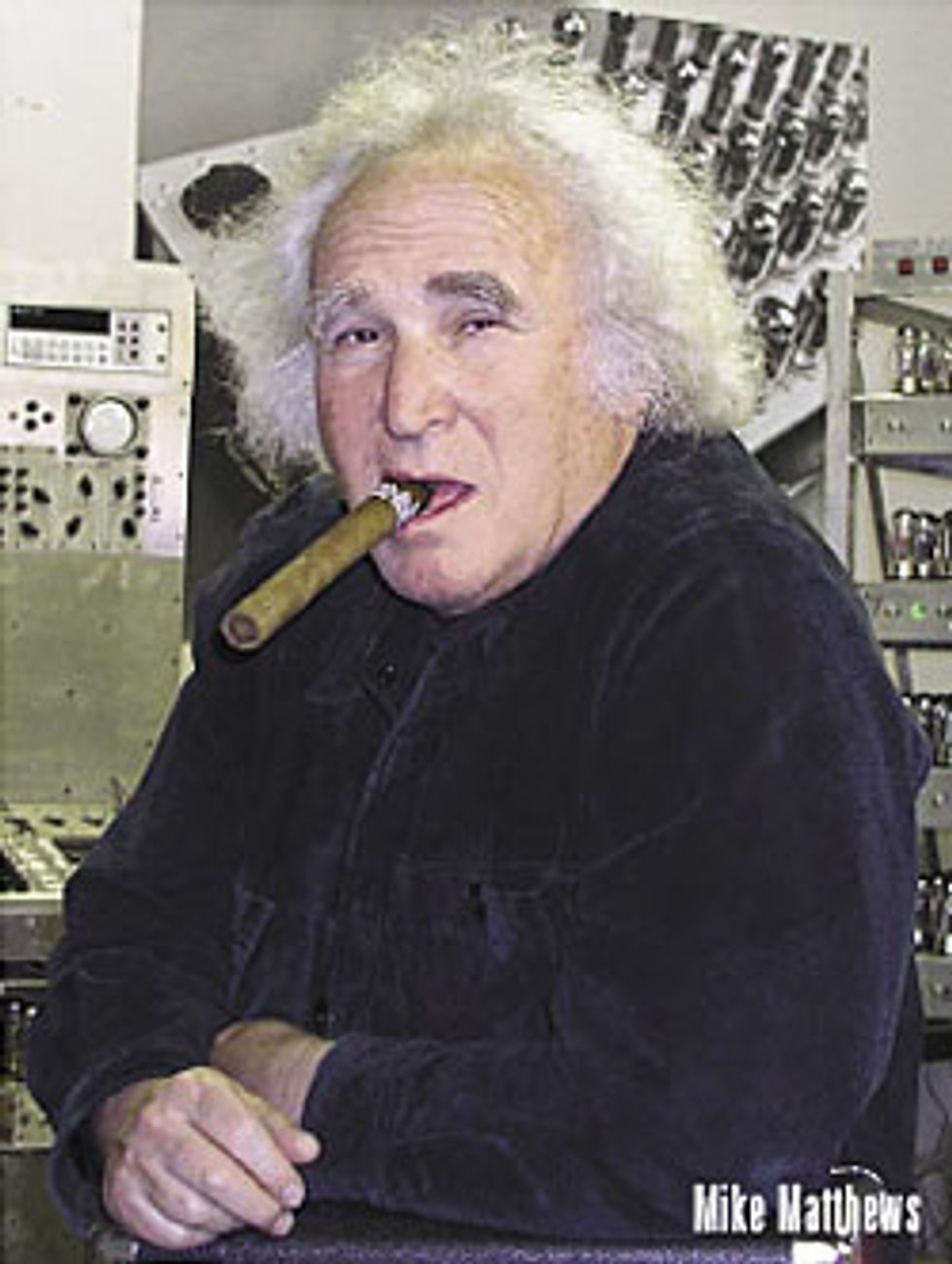

So Hazarai can loosely be defined as everything but the kitchen sink, but how does that apply to a delay, and reasonably sized one at that? For the answer, a little history might be in order. Formed in 1968 by renowned individualist Mike Matthews, Electro-Harmonix’ first product was the LPB-1, a preamp that was capable of hitting the front end of the then-clean tube amps harder than a drunk jaywalking at three in the morning, delivering sweet overdrive and distortion in the process. The line evolved, adding the Big Muff in 1970, which ended up in the capable hands of guitarists like Jimi Hendrix and Carlos Santana and went on to become the object of countless fuzz crushes, perfectly displayed in a droolinducing scene in Fuzz: the Sound that Changed the World featuring J. Mascis planted firmly in front of a china cabinet chock full of vintage Big Muffs. Delving into time-based effects in the mid-seventies with the Electric Mistress flanger, EH was well on its way to mastering the tone-per-dollar equation by the time they released the Memory Man in 1976. Previously, electronic delays were the exclusive domain of recording studios, with tape delays being relegated to mere mortal use. When EH followed with the under-$100 Instant Replay sampler in 1980, more than minds were blown – Electro-Harmonix had firmly established their ability to consistently provide William Randolph Hearst tones at Cletus Delroy Spuckler prices.

1980 also saw the release of the 2 Second Digital Delay, the first affordable digital delay available, followed by the 16 Second Digital Delay in ’82, the first commercially available looper, demonstrating Electro- Harmonix’ early predilection for providing more in their delays, which is completely in line with the concept of Hazarai.

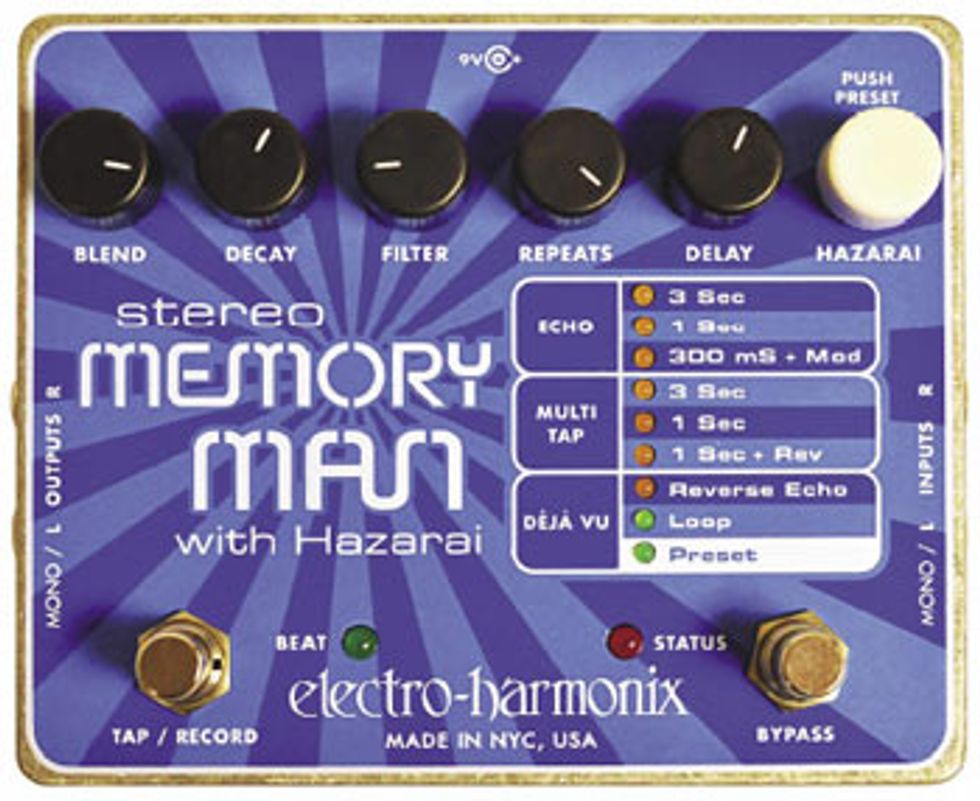

Making its buzz-filled debut at ’07 Summer NAMM, the Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai’s moniker seems apt; it’s the latest member of the EH pedal club, offering cutting edge features and idiosyncratic Electro-Harmonix musicality for dues that everyone can afford. To make sense of its deep feature set, we called upon John Pisani, one of the pedal’s designers, who was kind enough to chat with us about the inner workings of the latest in a long line of memorable EH effects.

Let’s talk about the name Hazarai for a minute – why did you decide to use it with this pedal?

Let’s talk about the name Hazarai for a minute – why did you decide to use it with this pedal? Well, we added the word Hazarai because we wanted to create a delay pedal that was over the top with features – as many as we could in a relatively small package and not go overboard with controls.

Can you tell us how the design process started on the Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai?

The Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai came about when Mike decided that we should have a couple of digital delay products that weren’t based on anything from the past. Out of that idea came the Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai and the #1 Echo. The #1 Echo is a smaller, much simpler digital delay.

I was able to check that out at Summer NAMM – it was released at the same time as the Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai, right?

Yeah, they were both sort of made in tandem. So for the Hazarai we used our Chief Design Engineer David Cockerell who has designed numerous Electro-Harmonix pedals, both in the seventies and this decade, like the Micro Synthesizer, Bass Micro Synthesizer, the Small Stone, the original 16 Second Delay, the 16 Second Delay reissue and the 2880.

So he’s no slouch.

Yeah, exactly. He designed the Instant Replay, which was one of the first inexpensive samplers. Not only that, he went on to design most of the Akai samplers, in addition to dozens of other EH pedals. More recently he has designed the the HOG, the software for the POG, the Micro POG, the Stereo Electric Mistress – our new digital flanger and the Hazarai. Mike and I went over the concept for the two delays and we told David what we were looking for in the Hazarai, and he came up with a circuit and functional front panel – knobs, indicators, things like that. We tweaked a few things and he went about writing the software. The thing about the Hazarai is that it’s a digital pedal, so nearly all the processing – all of the fun stuff – is written in software.

We came up with some of the algorithms together, including the Reverse Echo and the Looper. We really wanted a full-featured looper, even though the Hazarai is primarily a delay/echo pedal. With all of the competition out there we decided it needed to include overdubbing capability. You can also overdub onto the loop with the echo, so you can go to any echo mode – or Reverse Echo or a Multitap Echo – and record the loop with your echo. It’s really unique.

Digital makes sense for time-based effects, but do you see non time-based effects entering this realm in the future?

To a certain degree I do. Consider what we have out already – the POG and the HOG are both non-time-based effects that are completely digital. They are both basically pitch shifters, so they’re unique compared to what’s out there. Even though EH will probably have a finger in every sort of technology – tubes, transistors and digital – I definitely see us heading in a direction where we’ll be writing more software for our DSPs, and the software won’t necessarily be delays, flangers or choruses, but other interesting effects that are mathematically intensive and therefore hard to produce in the analog world.

Do you think distortion effects and overdrives will remain analog or do you ever see that going digital, too?

I do see it going digital, but not 100 percent. We’ll still be making analog distortions like the Big Muff, the Muff Overdrive, the Metal Muff and the English Muff’n. Tube and transistor distortions need to use analog circuitry for that particular sound. We don’t really have much interest in modeling something like the Big Muff or coming up with a digital version of it, but we would be interested in coming up with a different type of distortion that can only be done digitally.

I was assuming that since we are running out of some very specific chips that you would eventually have to go digital. You’re saying as long as there are IC chips, you can find something to work?

Yeah, I would say that’s essentially true. The chips that we do run out of, like the Panasonic MN3005 in the Deluxe Memory Man, do one very specific job – delay a signal by however long you need it to be. But the transistors in the Big Muff, for example, could be used for anything. I can’t see a point in the future when they’ll stop making those.

The circuitry to make a fuzz tone is relatively simple, but the corresponding signal that comes out of the output is very complex, which seems much more difficult to replicate digitally.

As simple as the circuits are for fuzz tones, the amazing thing is how much component tolerances, the slight changes in components – whether it’s a resistor or capacitor – really change the sound. That’s why some people think distortion pedals from the seventies sound better. It’s the subtle differences in component tolerances and the way the components have been made. It really makes a huge difference in things like distortion, but digital pedals can absorb component tolerances a lot better than analog pedals.

Can you explain that?

Can you explain that? For the majority of digital pedals out there, all of the processing work is happening in the DSP chip and processor, and the sound is being manipulated and affected by the software running on the processor. That software never changes. Every digital pedal needs analog circuitry supporting it – A/D and D/A converters at the very least. Those types of circuits are very common and they don’t change much from chip to chip. Different A/D and D/A converters with similar specs get a similar sound.

So once you’ve got a design together and you’re happy with the way everything is working, at that point it’s easier to build consistently. You sent us a Hazarai to check out a month or so ago – if you sent us another one tomorrow, it would sound the same.

Exactly, it takes inconsistency out of the equation. With all-analog circuitry there might be some variance due to chip tolerances and various things.

How do you guys handle that variance in your analog pedals?

We use resistors and capacitors with low tolerances. If you were to measure a bag of resistors they would all be within plus or minus one percent.

"With the Hazarai we tried to throw in everything you would want from a digital delay pedal, from tapping in the delay time to having the ability to create loops on the fly"

So you use really close tolerances – not plus or minus five percent?

Sometimes we do use the plus or minus fives – that’s only one way we try to do it. Another way is circuit tricks that help make those tolerances less noticeable. A very popular one is to use negative feedback around the transistor. That helps to subtract out any variance from transistor to transistor.

So by using tighter tolerances and specific design choices you can keep the variances to a minimum.

Even with all that, in something like a Big Muff, there are some variances from unit to unit. One thing we don’t have control over are the pots themselves. The pots tend to have huge tolerances, like plus or minus ten percent. It’s very difficult to get a tighter tolerance on a pot, so if the pot itself is in the middle of a tone circuit, then it’s going to cause differences from unit to unit.

Is it just the quality of pots that are available now?

It’s always been the case. I’ve never done this, but if you were to take five Big Muffs from the same production line from 1973 and listen to all five, you would probably hear something different out of every one.

So with analog circuitry, it seems like more of a holistic approach – you have to be concerned with every component.

Yeah, every component in the design has a purpose, but nearly every component in an analog pedal actually touches the signal; that’s not typically the case with a digital pedal. With digital designs you have components that never even see the signal – all they see is the digitized version of it.

During the process of designing the Hazarai, were there any specific challenges that you weren’t expecting? It sounds like everything went really smoothly.

[Laughs] Yeah, I know, I guess it’s kind of boring. Part of the reason everything went so smoothly is that [David] Cockerell is a very experienced designer, so he knows what he’s doing. As far as the circuitry goes, the digital pedals tend to be very similar from design to design; they have an A/D, a D/A, a processor, some analog circuits at the front end, the output and a power supply. So, if you’ve designed one, in a sense you’ve designed a million. By the time he went about designing the Hazarai, he pretty much knew what was going on and what would and wouldn’t work.

What was your role on the team while you were working on this?

My main role was project management, making sure deadlines were met, even though we didn’t have any hard and fast deadlines. In addition, I did much of the testing of the Hazarai. David would send me a software update, I would listen to it and make comments – this is good, this isn’t, or we want it to work differently. The best example I can give you is the Reverse Echo, which hadn’t been designed or written in the software until later in the design process. My part in that was coming up with an idea for how the algorithm should work – like we want to have a note detector that can tell when the player plucks a note and then at that point the Hazarai is going to reverse the delay. So I wrote down some ideas for David on how the echo should work and he made that happen. It took a few tries – we went back and forth five or six times before we eventually got it.

Was that time frame typical of a new pedal?

Was that time frame typical of a new pedal? I would say the Hazarai actually took a shorter amount of time than the typical digital pedal, and I want to clarify digital. The reason is that because much of the circuitry used in the Hazarai was in the 2880 and in the HOG pedals, so we were able to take what we needed from those two pedals to go into the Hazarai.

Does that speak to David’s involvement with all of those pedals?

He designed all of those pedals, and since he already had a design in place from the 2880 and the HOG, which use the same basic chips as the Hazarai, he was able to use all that circuitry and pare it down – we didn’t need everything that was in the 2880. A lot of the circuitry of the Hazarai was already tested, already established, already known, so it was a relatively quick design process because we had already established the most important chips in the circuit.

Was the end product price a consideration at this point?

At the beginning stages, it wasn’t. For the #1 Echo, price was a consideration – we wanted to make that competitive, but with the Hazarai we decided to pull out all the stops.

That must be nice from a design standpoint.

Well, we knew we couldn’t go overboard, but we also knew we had a little bit of leeway. With the Hazarai we tried to throw in everything you would want from a digital delay pedal, from tapping in the delay time to having the ability to create loops on the fly. We wanted to make a really good sounding digital delay with modulations and filtering – we threw it all in. We even got some reverb in there, which was a surprise. It wasn’t on the original specs but I’m glad it’s there.

What do you use to program this? I envisioned oscilloscopes everywhere, but the way you’re describing it, it sounds more like sitting in front of a computer display.

We are planted in front of desktop computers. We have our scopes and our waveform generators, which we use to test the circuits and the software, but instead of soldering and trying different component values, most of the work is done with software, where a few lines of code are written and we try it out.

Can you tell us more about the Looper function?

With the Looper, we looked back at some older pedals, and we always liked the infinite function, which takes whatever is in the delay’s memory at that time and loops it forever but it doesn’t record any new audio. We kicked around the idea of having that in there, but ultimately we decided that as nice as that is, it would be more useful if the musician could record the echoes and delays as they’re hearing them, creating a loop if they wanted. With the Hazarai, you can record a loop while you’re playing any of the echo effects, with one exception. The Looper records the output of the Blend knob, which is essentially the last stage, so it’ll record the loop as you hear it, which is an important feature that we wanted.

What is the echo function exception for recording loops?

The one exception is the mode that’s called One Second plus Reverse. The looper works by holding down the tap footswitch to record the loop, but the tap is also a multi-function switch – you can set the tap tempo if you press and release the switch at least two times. Since the Hazarai has the ability to play back whatever you just played in reverse, when you’re in the One Second plus Reverse mode, the tap switch plays back your previous six seconds in reverse. I want to clarify that you can still tap, because in a YouTube video that somebody made…

Is that the one with the echo guy with the disco light on the desk?

Yeah, in that video, there’s one error: they say that you can tap in any mode except the One Second plus Reverse mode, but that is not true, you just can’t record a loop in that mode.

Let’s talk about getting signal in and out.

The Hazarai features stereo ins and outs. You could have a left and right input and a left and right output, and they will stay separated. You could also do mono in and stereo out: plug in your mono guitar and then you go out to two amps or two channels of a mixer. In that case, the Hazarai will ping pong between the two outputs. So while you’re in your echo modes, let’s say you have the Multitap Echo with six repeats. The first repeat will go out to the left side, second repeat will go out to the right side, and so on. You can get this really great back and forth effect. And of course, there is mono in and mono out.

So if you’re coming from a stereo chorus pedal, you could bring that stereo signal in.

Yeah, exactly, keep that stereo chorus in stereo.

What are you working on now?

What’s next for us is we have a lot of things on the table right now, but I would say the biggest thing for us right now is that we’re getting into making bass guitar effects – we have five or six bass guitar effects in the works. The first one that is coming out we took to NAMM. It’s called the Steel Leather, again designed by David Cockerall. It’s a bass expander, a pedal that accentuates the attack or the picking of notes when you play bass. It’s really cool.

Click here for videos of the Electro-Harmonix Memory Man with Hazarai

Electro-Harmonix

ehx.com