This past June, onstage at a handsomely restored vaudeville theater in Washington, D.C., the guitarist and composer Andy Summers made a small but spirited crowd laugh. Hard.

Summers, who rose to fame in the late 1970s as one third of the new-wave phenomenon the Police, told many stories and landed many punchlines. There was the episode in which he and John Belushi partook of psychedelics in Bali, and the time he got kind of hustled by a striking, guitar-playing Long Neck Karen villager in Thailand. He recounted a gut-busting tale of taking a few too many sleeping pills on a trip to South America. With perfectly British dryness and timing, he improvised an aside about living near Arnold Schwarzenegger in Los Angeles, and how he just had to kick the Terminator’s ass.

Out of the Shadows

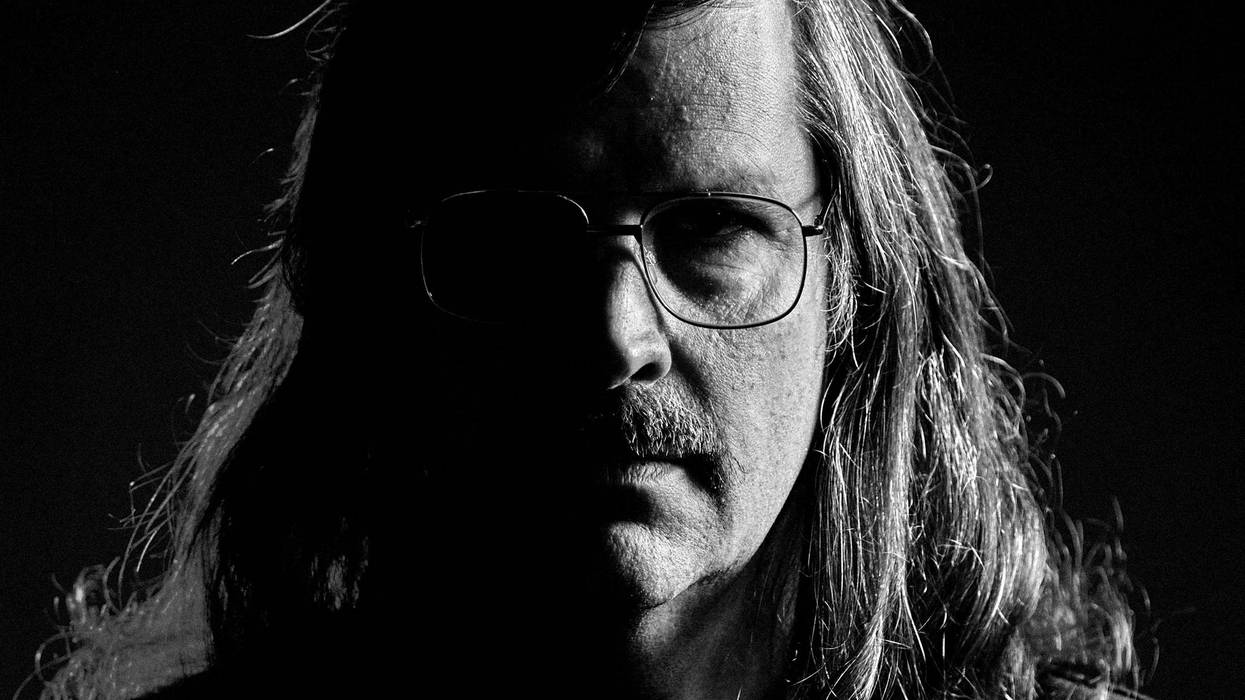

“I think it’s turning into a standup routine, basically,” Summers said recently over Zoom. He was being self-effacing. Mostly, this one-man multimedia show, entitled “The Cracked Lens + A Missing String,” allows Summers to reflect on enduring passions with sincerity, by “integrating these two media I’ve been working on for so long”: music, of course, and art photography, where his work combines painterly composition with street-level intimacy and the global-citizen mission of Nat Geo.

Behind projections of his photos, and between the storytelling and odd video clip, he gave a two-hour recital of solo guitar music. Summers played a new yellow Powers Electric A-Type guitar, and began his show by telling his audience how thrilled he was with it. (Summers has accrued around 200 guitars, many of them given to him, and maintains that he’s “definitely a player,” not a collector.)

Summers spent a significant part of his 20s studying classical music, originally inspired by Julian Bream. Now, onstage in his one-man show, it's clearly time to reflect on his past.

Summers began touring “The Cracked Lens” before the pandemic—the final show prior to shutdown took place at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in 2019—and picked it up last year. It’s evolved, he says, through improvisation and trial and error, following a process much like one he’d put into motion for any band or project.

In D.C., the setlist was both surprising and deeply satisfying. Newer solo music like “Metal Dog” came off as delightfully arch and abstract, a reminder that Summers hit the Billboard albums chart with Robert Fripp, with 1982’s I Advance Masked. A sterling chord-melody arrangement of Thelonious Monk’s “’Round Midnight” spoke to the lifelong impact American jazz has had on the guitarist. A winsome mini-set of bossa nova, including “Manhã de Carnaval,” Luiz Bonfá’s theme to the film Black Orpheus, illustrated Summers’ devotion to both the cinema and the music of Brazil.

And yes, there was Police material, too, which Summers reharmonized and rearranged and used as vessels for longform improvisation. Atop programmed backing tracks, he treated songs like “Tea in the Sahara,” “Roxanne,” “Spirits in the Material World,” and “Message in a Bottle” as if they were his beloved jazz standards, drawing agile lines in and around the harmony, using pop hits as a launch pad for wending single-note narratives. In a small theater, it felt as if you were eavesdropping on Summers, whiling away an afternoon in his home studio. An excitable woman behind me couldn’t help but try and banter with him as he stalked the stage; the guy to my right played air drums. This was thrilling—especially if you were a Police fan whose context for these songs was sold-out arenas.

A New Installment

To combine music and imagery was also the impetus for Vertiginous Canyons, Summers’ recent solo EP. Commissioned as an accent to the guitarist’s fifth photo book, A Series of Glances, the project features eight spontaneously composed instrumental pieces of pop-song length. Its sparkling, layered, and looped soundscapes serve as Zen-like mood music for viewing the photographs. By design, Summers improvised Vertiginous Canyons in a single afternoon without too much fuss, using mostly his early ’60s Strat. “This was drone-like, ambient, atmosphere stuff that I thought was enough,” Summers explains. “Because I suppose you could get into a place, let’s say, where the photography and the music are fighting each other.

“One of the cardinal rules of scoring films, which I’ve done many,” he adds, “is don’t get in the way of the movie.”

On Vertiginous Canyons, listeners will hear influences from Eno to Hendrix to Bill Frisell.

As with Summers’ solo show, the music can stand alone. In many ways, Vertiginous Canyons also comes off like Eno or classical minimalism or the edgiest strain of what can be called “new age”—an engaging yet accessible entryway to experimental music. And as with any effective musical abstraction, what you’ve heard in your life is what you’ll hear in Vertiginous Canyons. The twinkling, fluttering phrases of “Blossom” bring to mind Bill Frisell. “Translucent” and “Village” summon up Glenn Branca’s guitar armies in their quietest moments, ramping up toward euphoria. “Blur” is a far-out exercise in Hendrix-style backwards soloing; “Into the Blue” is Pink Floyd meets Popol Vuh.

Greatly moved by Julian Bream as a young man, Summers spent a sizable chunk of his 20s immersed in classical guitar in California, as hard rock and the singer-songwriters ascended. When I ask him if those studies informed Vertiginous Canyons, his response is rapid-fire. “Definitely. I mean, I spent years doing nothing but classical music, classical guitar,” he says. “It’s very important information that I took in … and it stayed with me the rest of my life.

“So my ears are wide open.... I’m a sophisticated harmonic player, and it’s also informed by classical music. I’m sort of all-’round educated in the ways you can do music.”

Summer Reflections

To let an artist’s age guide your judgment of them is unfair. But in Summers’ case, it’s essential to understanding how and why he became such a fascinating guitarist, one whose whip-smart, cross-cultural approach overhauled the prevailing notion of what rock-guitar heroics could be in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

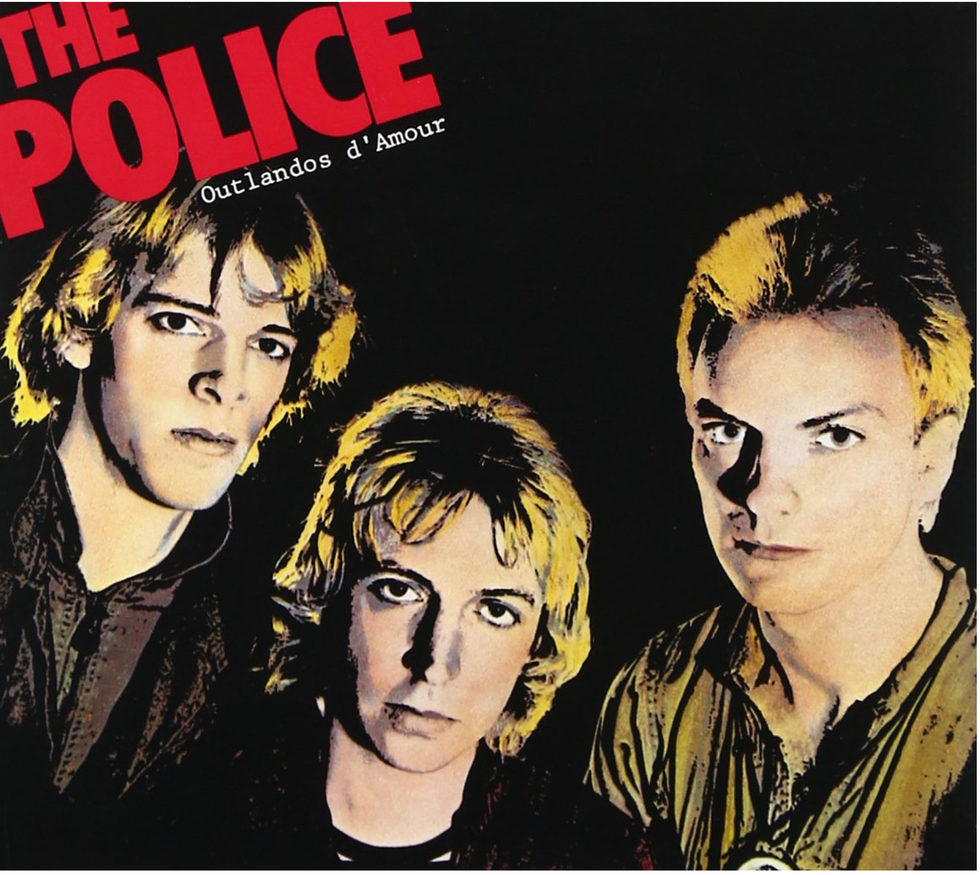

He was born on the last day of 1942, “a kid from the English countryside,” he says. His father was in the Royal Air Force; his mother supported the war effort working in a bomb factory. Alongside Django Reinhardt, he’s on the short list of guitar idols who spent their earliest days in a Romani caravan, which his father bought in the face of a housing shortage. In terms of rock generations, think about it: Jimi Hendrix was born in November of ’42, Keith Richards in ’43, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page in ’44, Pete Townshend and Eric Clapton in ’45. Summers debuted the cinematic, reggae-soaked sound that made him famous on the Police’s Outlandos d’Amour, in 1978, as the punk explosion gave way to post-punk and new wave. But his contemporaries are the British bluesmen who were architects of the psychedelic era and won over the baby boomers.

Andy Summers' Gear

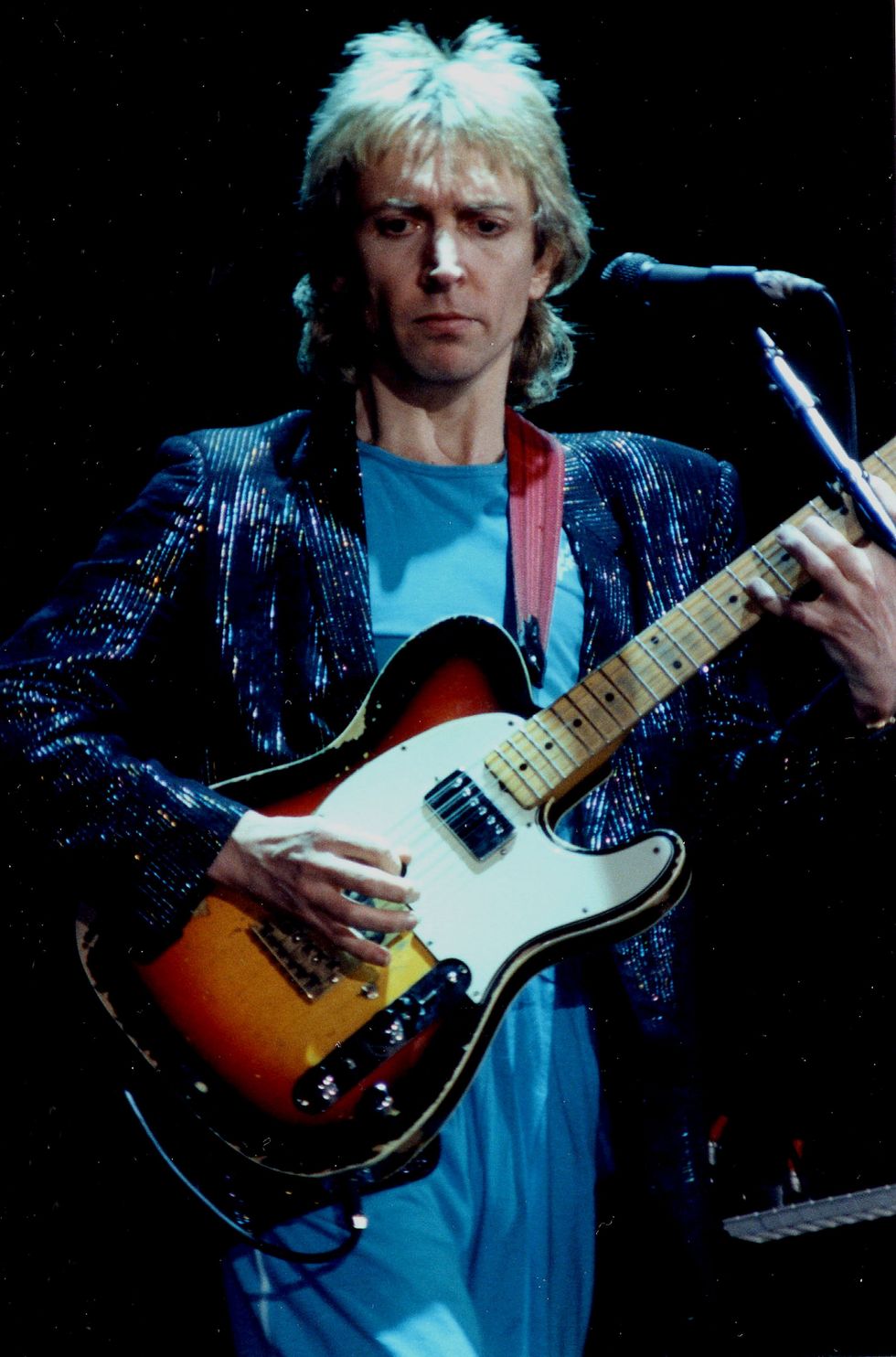

When Summers, pictured here performing with the Police in 1982, began developing his blues chops, he blended in complex chords and jazz phrasing.

Photo by Frank White

Guitars

For touring:

- Fender Custom Shop Stratocaster

- Powers Electric A-Type

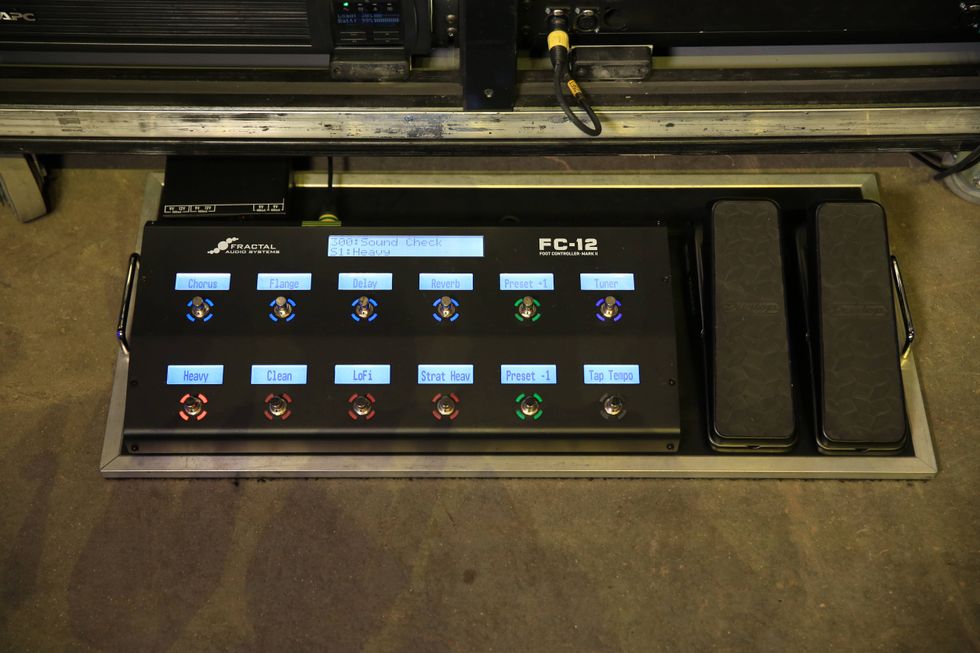

Amps

- Fender Twin with Fender Special Design Speakers

- Fractal Axe-Fx III

- Bob Bradshaw 100-watt head

- Roland JC-120

- Various Mesa/Boogie heads, cabinets and power amps

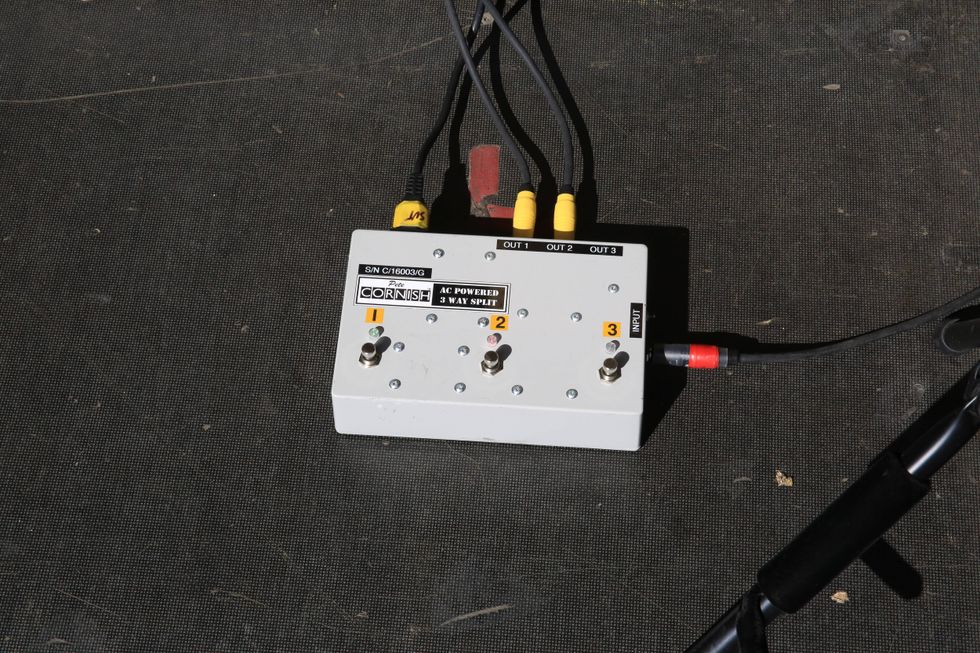

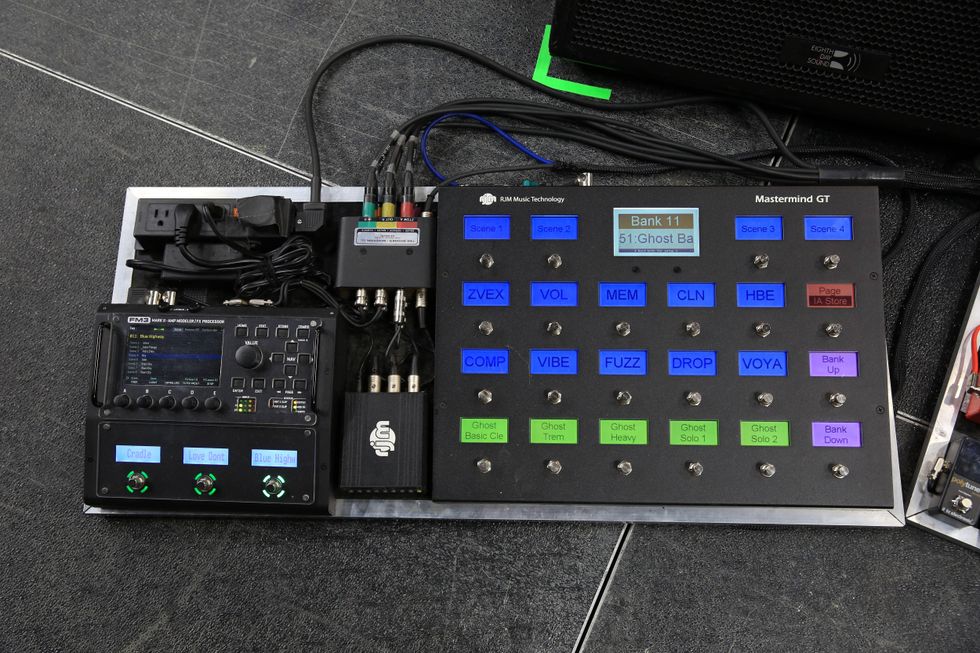

Effects

Current Pedaltrain pedalboard includes these effects, among many others:

- TC Electronic SCF Gold

- Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

- DigiTech Whammy

- Klon Centaur

- TC Electronic Brainwaves

- MXR Carbon Copy

- Electro-Harmonix Freeze

- Paul Trombetta Design Rotobone

- TC Electronic Dark Matter

- Mad Professor Golden Cello

Picks & Strings

- Dunlop Andy Summers Custom 2.0 mm Picks

- D’Addario Strings, mostly .010–.046

The electric-blues revivalism that his peers favored was a scene with which Summers engaged mostly by circumstance. In some capacity he was immersed in it, gigging and recording with hot R&B acts of Swinging Sixties London. But as a developing guitarist, he also transcended its stylistic boundaries, and he ultimately missed out on the wildly lucrative parts of it, after it’d evolved from nightclub entertainment to chart-topping, festival-headlining pop.

“[We’re talking about] real modern electric-guitar history,” Summers says, “because I was really pretty close with Clapton. We all knew each other. There were about five or six of us, and we all played at one club [the Flamingo, in London].

“I watched Eric develop, and he had this mission to play the blues … and he ripped off some great blues solos,” Summers adds, with a mischievous chuckle. “I had grown up with different kinds of music in those formative [teenage] years, when you’re taking it all in and trying to be able to do it.”

So much has been written about how the ’60s British-guitar titans tapped into early rock ’n’ roll influences and Chicago blues, rescuing the latter from obscurity in its country of origin. But it’s important to remember the profound impact that midcentury modern jazz had on culturally curious young Brits; in fact, the moniker “mods”—that clothes-obsessed cult that gave us the Who—began as “modernists,” as in devotees of modern jazz, R&B, soul, and ska.

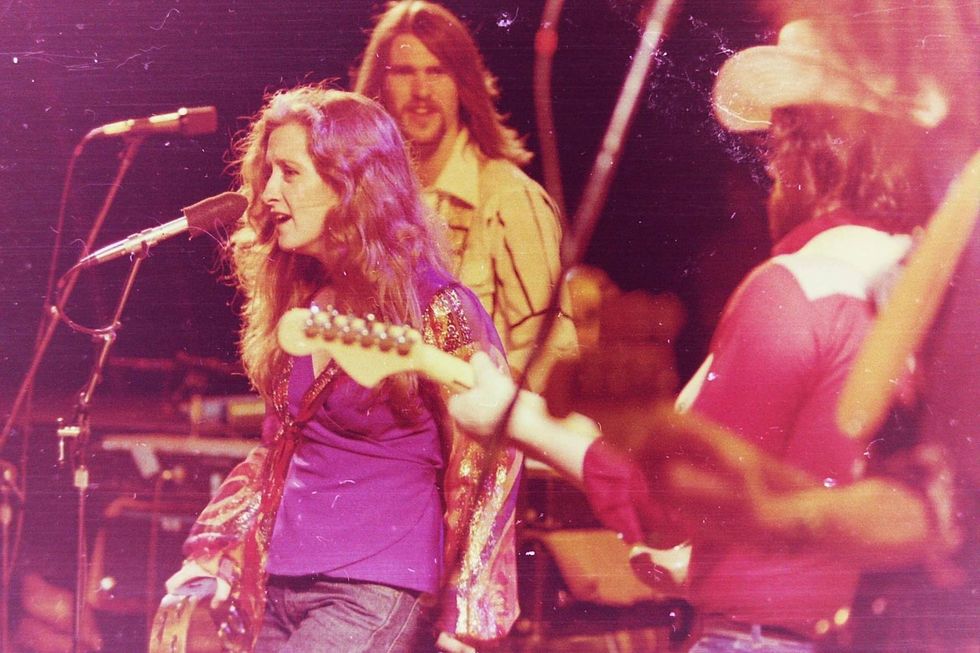

Before meeting Sting (left) and forming the Police, Andy Summers (right) was close friends with Eric Clapton and once jammed with Jimi Hendrix.

Photo by Ebet Roberts

Summers was hooked. Guitarists Wes Montgomery, Jimmy Raney, Kenny Burrell, and Grant Green ranked among his favorites, alongside Sonny Rollins. Rather than sticking to 12-bar patterns, Summers shedded on complex chord sequences and jazz phrasing, logging “thousands of hours of listening, trying to get it. But that’s where the feel of the time comes from, which is the most important element.”

“Eric and I talked about it,” he continues, “and I was in a different place. I don’t think we really had arguments about it, but he was absolutely a disciple of the blues, where I was more into other things.” Summers loved the fleet, chromatic lines of bop, and classical guitar, and African and Indian music. He recalls transcribing Ravi Shankar.

“So I felt like I very much had my own path, and it wasn’t the Eric Clapton path. I was aware of all that, but Eric was deeply into B.B. King — gave me his B.B. King record, actually—Live at the Regal, told me to check it out. So I did listen to it, and yeah, okay, I get it. But my head was elsewhere.” (During that period, Summers also sold Clapton a ’58 Les Paul, after Slowhand’s 1960 model was stolen. “It was guitar craziness,” Summers says. “I really anguished over selling my Les Paul, but I just wasn’t into it. I think there was something wrong with the pickup—at least I thought there was, in my sort of naivety at that time.”)

Nor was Summers’ path the Hendrix path. Because of his friendship with the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s drummer Mitch Mitchell, Summers once jammed in the late ’60s with Jimi. “A quiet guy with a very loud guitar. And he could play the shit out of the guitar,” Summers laughs. “He was definitely sort of a force of nature. You’d feel it.” At an L.A. studio where the Jimi Hendrix Experience was in session, Summers began playing with Mitchell on a break. But “Jimi just couldn’t stay away from the music,” Summers recalls. So Hendrix picked up a bass to anchor Summers’ guitar, until Jimi asked to trade.

“I think of it almost as a sort of a comic moment,” Summers reflects today. “Jimi had come into the scene and … didn’t really play like anyone else. I mean, he played Jimi Hendrix … incredible, but I didn’t really want to play like that. I’ve got to find my own thing. It was very imperative to me not to be yet another Hendrix copier. And I think it’s what he would have appreciated, too.”

Although the first album by the Police was released in late 1978, Summers already had an extensive catalog of recordings with Eric Burdon, Kevin Ayers, Kevin Coyne, Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, and Joan Armatrading before “Roxanne” alerted the world that a new kind of pop group was arriving.

To hear Summers on pre-Police recordings is intriguing; even on straightforward forms, his good taste and sense of harmony present a shrewd, knowing alternative to his peers. Seek out the 1965 LP It Should’ve Been Me, by Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band: On a take of Jimmy Reed’s “Bright Lights, Big City,” Summers applies the single-note harmonic finesse of Grant Green to barroom British R&B. (It was Green’s Gibson ES-330, a surprising instrument for a jazz picker at the time, that inspired Summers to pick up an ES-335 after his ES-175 was stolen.) A few years later, as part of Eric Burdon’s New Animals, Summers covered Traffic’s “Coloured Rain,” going long on a fuzztone solo that fits the psychedelic bill while also telling a story with precision and patience.

Summers’ ship came in nearly a decade later, after he’d returned to England from California and met drummer Stewart Copeland and a singer and bass player, Gordon Sumner, who went by “Sting.” They were bright, dexterous, and culturally well-versed, with backgrounds in prog and jazz. “I think we had a credo,” Summers says, “and it was spoken out loud: We don’t want to sound like anybody else.

“I found I could talk to Sting and say, ‘I want to play this kind of altered chord here. What do you think?’ He could sing right through anything. He had the ears to be able to sing it like a jazz singer. Not that we were trying to lay ‘We’re really jazzers’ on the public. We were trying to present ourselves as a rock band with songs. But the information that we were putting into those rock-song arrangements was different.”

Summers in a late ’80s promo photo, near the start of his solo-recording career.

For Summers, that meant matching the musicianship he’d started earning as a teenager on jazz bandstands with the au courant sounds of post-punk and reggae, filtered through emergent sonic technology. With his heavily modded 1961 Tele and custom Pete Cornish pedalboard, he offered chord sequences and lines that have challenged and educated generations of practicing guitarists brought up on blues-rock technique. Alongside his deft use of open space, he was that rarest rock guitarist who paid serious mind to chord voicings. “My job was to turn the chords into something more unusual,” Summers says, “to have more unusual guitar parts. For instance, something like ‘Walking on the Moon,’ I put in a Dm11 chord, with reverb and a beautiful chorus sound. So it’s got the 11th on top, and immediately it grasps your ear. It’s like the signature of the song was that chord.”

“So my ears are wide open.... I’m a sophisticated harmonic player, and it’s also informed by classical music. I’m sort of all-’round educated in the ways you can do music.”

Of course, no other Summers guitar part or Police song made bigger waves than 1983’s “Every Breath You Take.” Influenced by Bartók’s “44 Duos for Two Violins,” Summers crafted a repeating figure that underlined Sting’s standard pop-song structure while avoiding conventional triadic harmony. (Losing the third from tired rock chords was Summers’ not-so-secret weapon.) “It gave it that haunting quality that made the whole track come to life,” Summers says, “because otherwise, I think we would have dumped the song. It wasn’t one of our favorites at all.”

The Police last performed on their historic reunion tour of 2007 to ’08, and their relationship today is mostly business. “We’re not hanging out with each other,” Summers says. “We’re all in touch through headquarters.” One thing they’ve had to agree on this year is a Super Deluxe reissue, toasting the 40th anniversary of the Synchronicity album, which provides new context that might safely be called revelatory. Among the new box set’s many previously unreleased goodies is Sting’s original demo for “Every Breath You Take,” weighed down with synth keyboards that pile on the sentimentality and pin the track squarely to the 1980s. (Unlike so much ’80s pop-rock, the Police’s music has aged well.) “You can see the transformation,” says Summers.

“Every Breath You Take” became a global smash that ranks among pop’s most successful songs, a feather in the cap of the band that owned the late ’70s and ’80s. Consider this: At a time when his psych-era peers were considered middle-aged Flower Power relics, Summers was leaping around onstage like a bleached-blond atom and representing pop rock’s bleeding edge on MTV. Now, at 81, he’s found a way to forge ahead and, in some fashion, improve on the past.

Call The Police (Andy Summers / João Barone / Rodrigo Santos) - Synchronicity II (ensaio/rehearsal)

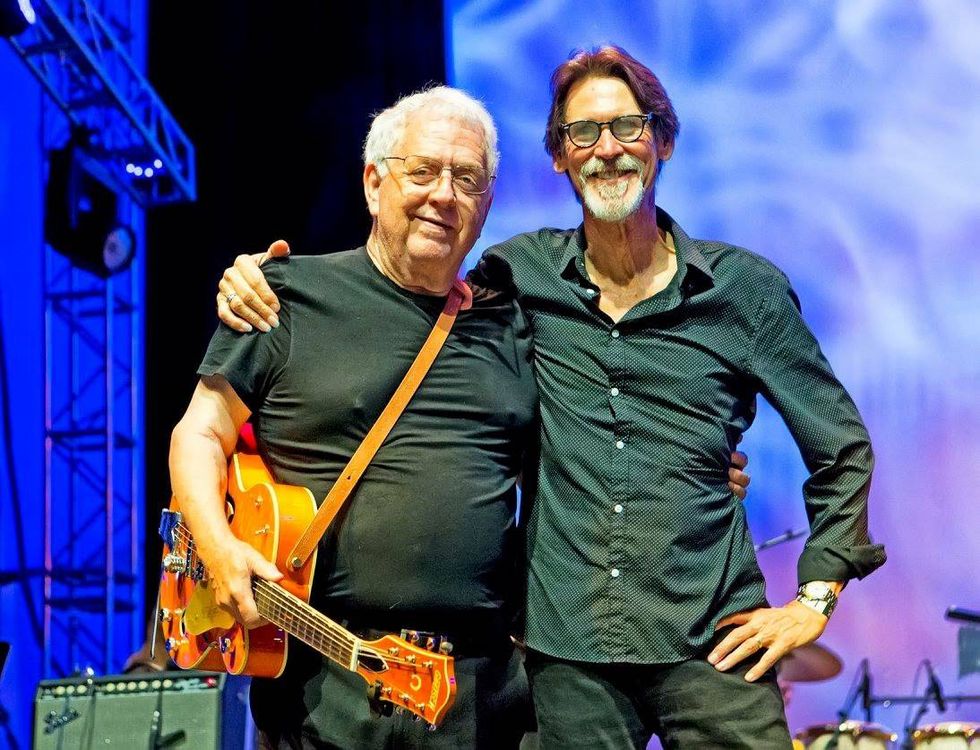

With bandmates João Barone and Rodrigo Santos, of Police tribute band Call the Police, Summers displays the adept riffage that brought him to the big stages and helped solidify his rock legacy.

Leveling Up

When we connect on a followup call in mid July, Summers is in Brazil, about to embark on a South American tour with his trio, Call the Police. This tribute project of a sort features two celebrated Brazilian rockers, bassist-vocalist Rodrigo Santos and drummer João Barone, and plays hits-filled live sets to packed houses. “It’s sort of enhanced, because it gets looser. It’s a bit uptight with those other guys I play with,” says Summers.

With regard to those other guys, that uptightness had much to do with the punk and new-wave era that bore the Police. The relationship between punk and the band was complicated. Somehow, they managed to use the movement’s greatest lessons—in energy, creative bravery, and concise songcraft—without pandering to its musical primitivism. Summers’ reputation amongst guitarists rested in the minimalist intelligence of his decision-making; you kind of understood he could play anything, but he was mature enough not to. “I didn’t feel the need to crush everybody with every guitar part,” he says.

“It was more like a guitar solo is supposed to be a mark of the old guard. You weren’t supposed to be able to play; it was really that dumb.”

Nevertheless, he believes that punk’s principle of non-musicianship kept him from exploring the songs to their fullest. “I think I should have played more solos than I was given the space to do,” he says. “It pisses me off actually, because this came more from Stewart. When we started the band in the thick of the hardcore-punk scene, it was more like a guitar solo is supposed to be a mark of the old guard. You weren’t supposed to be able to play; it was really that dumb.”

“I was a virtuoso player,” he adds, “so it was very frustrating for me. Later, when we did sort of open it up, it really got more exciting. The fact that I could play as well as I did, I found it was a bit threatening. Because the highlight in a performance of a song … would be the guitar solo.”

As in “The Cracked Lens + A Missing String,” Summers can stretch out in Call the Police to his heart’s content. At long last. “It’s very improvised,” he says, “and they’re up to the level where they can do that. They go with me. It’s how it should always have been.”

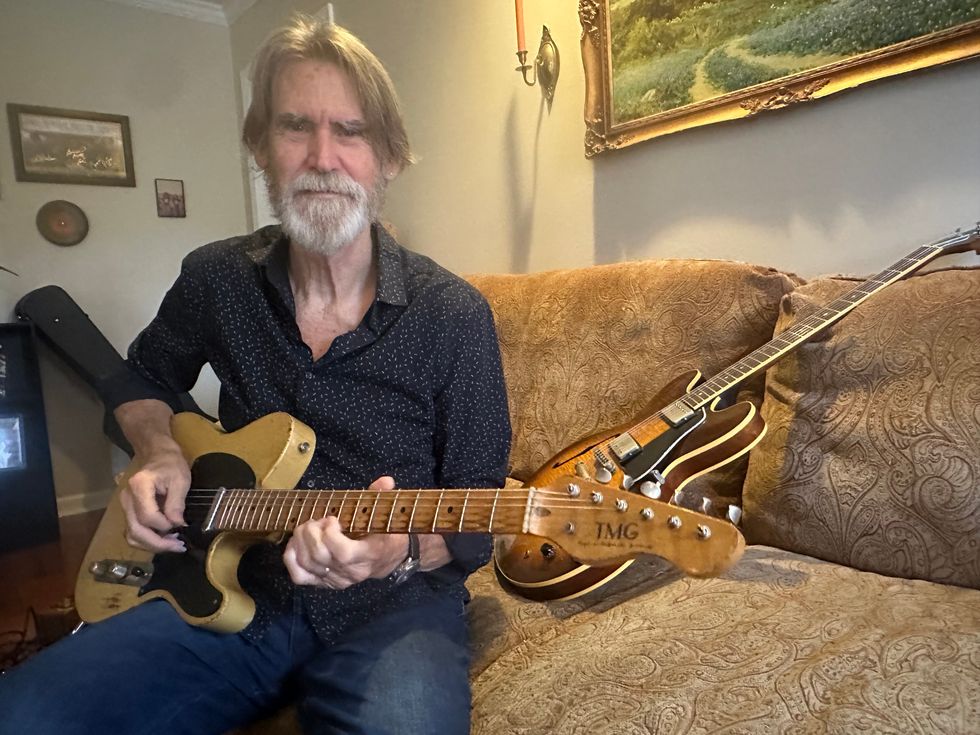

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski