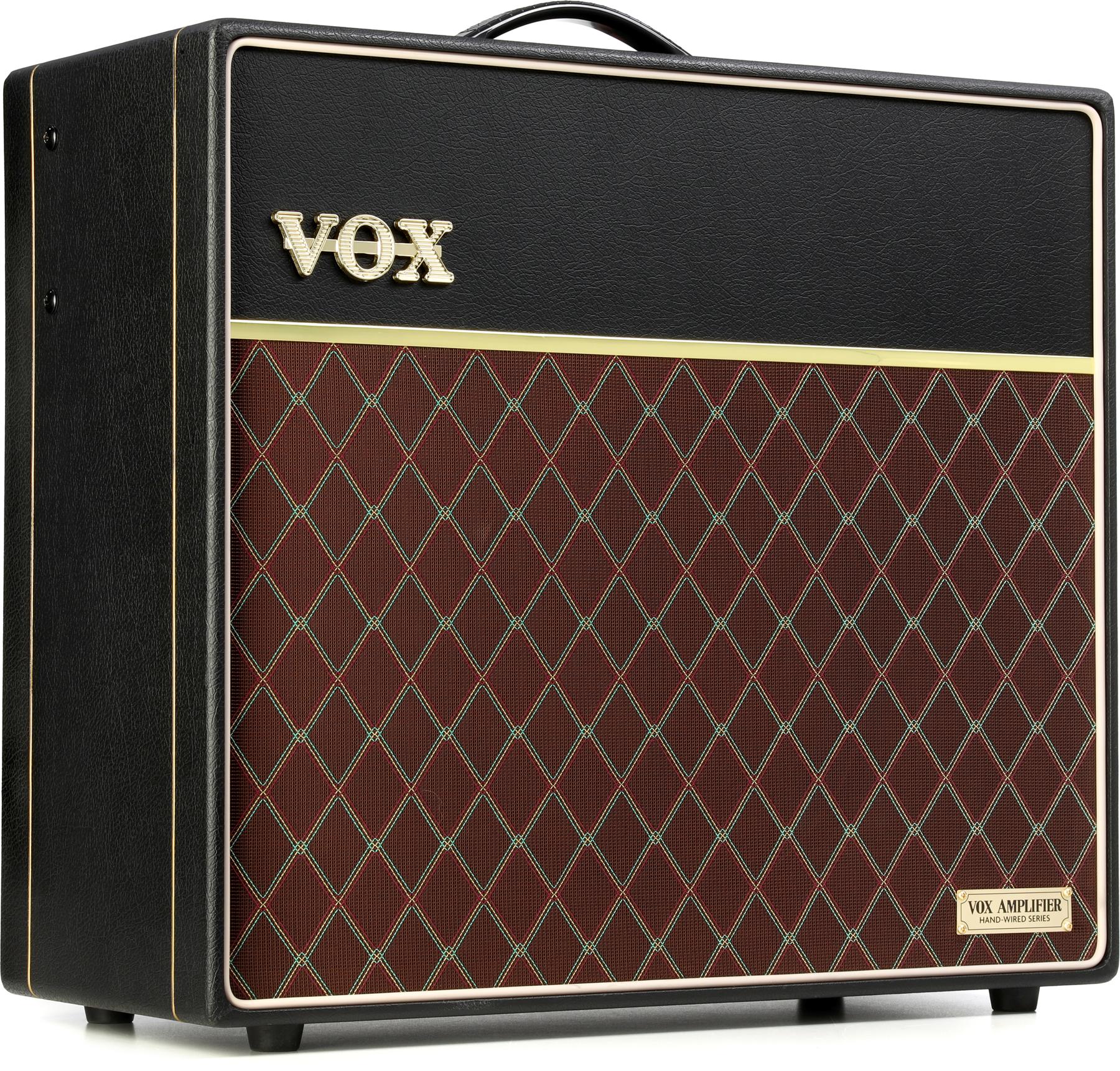

If you asked the average player to sum up a vintage Vox amplifier in a word, I’m guessing they’d say “chimey.” I never really understood the chimey thing. I mean, yeah, there’s chime in the complex tone composite that makes an AC30 an AC30. But for me, Vox amps of the 1960s, above all, sound exciting, thrilling, and potent. Chimey? That’s for dinner bells.

I know that Universal Audio did a good job of capturing the spirit of an AC30 in the UAFX Ruby ’63 amp emulation, because excitement is the first thing I felt. The Ruby ’63 is lively, explosive, reactive, clear, and, yeah, even pretty chimey. And I was very impressed at how it imparted those qualities to decidedly non-Vox-y black-panel Fender amps, and vintage Fender cabinet emulations in UA’s OX Amp emulator. You know how a lot of pedals claiming to be an amp-in-a-box tend to be vaguely similar in terms of EQ and gain structure, but miss the details? The Ruby ’63 is not that. It’s an exhaustively executed emulation that takes you several miles further down the road to true amp-ness. And it sounds and feels awfully close to the real thing.

Mod Cuts

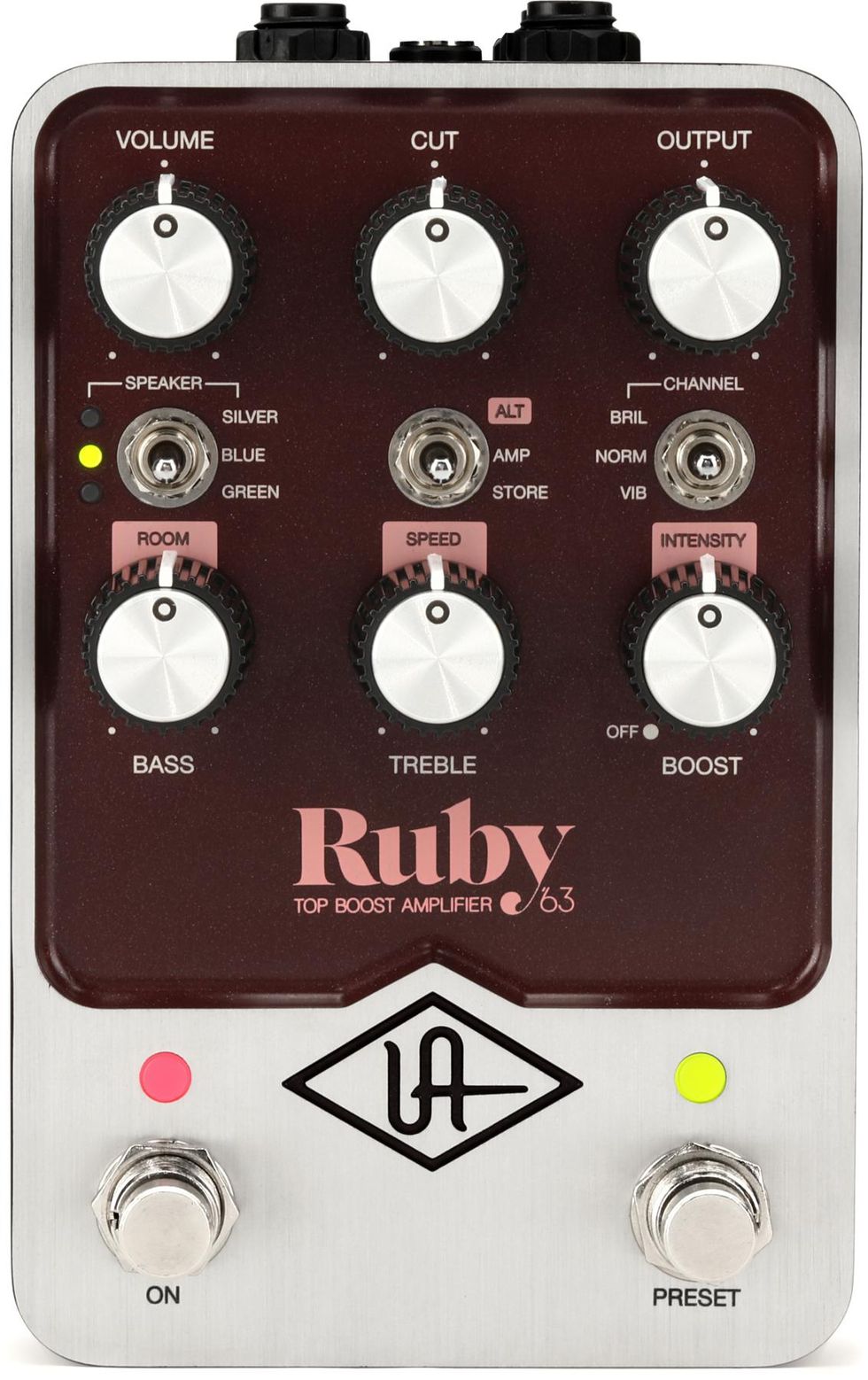

Universal Audio spends a lot of time studying interfaces of every kind—from those on ancient guitar amplifiers and outboard studio gear to the digital interfaces that make up their tracking and emulation software. The experience shows in the Ruby ’63. What stands out on the Ruby’s interface is economy. This pedal covers a lot of possibilities while barely deviating from the AC30’s control template. Of the six knobs on the Ruby ’63, four are the equivalent of controls on an AC30. Another two, the vibrato speed and depth, are available as secondary functions. UA adds a few goodies to enhance Ruby’s vocabulary. The brilliant control is paired with a Echoplex EP-3 preamp emulation. The normal channel setting is mated to a Rangemaster emulation, and the vibrato channel is mated to a clean boost. All of these boosters can be enabled or removed entirely via the boost knob. But I dare any reader to refrain from adding a touch of each respective boost when in the respective channel. They are, for the most part, the source of electric, ecstatic stuff.

The Ruby’s ability to process pedal tones in an amp-like way is one of its most impressive features.

One tone enhancement feature that isn’t an option on the average AC30 is the 3-way speaker toggle, which offers the option of moving between virtual Celestion silver, blue, and green speaker models—or no speaker coloration at all. The choices coax a lot of extra range out of the amp models, including some really beautiful high-mid activation from the silver mode.

Preset options aren’t abundant on the Ruby. You can only store one. But in my estimation, that’s plenty. I had much more fun using the single preset as a hot, boosted version of my base tone, and then blasting the pedal with a period-authentic fuzz, which, by the way, the Ruby reads and reacts to just like your amp would. The Ruby’s ability to process pedal tones in an amp-like way is one of its most impressive features.

Another impressive facet of the Ruby’s makeup is its modest but smart and effective connectivity options. Mono and stereo outs can be routed to amps, interfaces, or PA. You can bypass a real amp’s preamp in amplifiers that have an effects loop. Or you can also use a 4-cable method for switching between the Ruby with your real amp’s preamp section bypassed and your amp and preamp with Ruby bypassed.

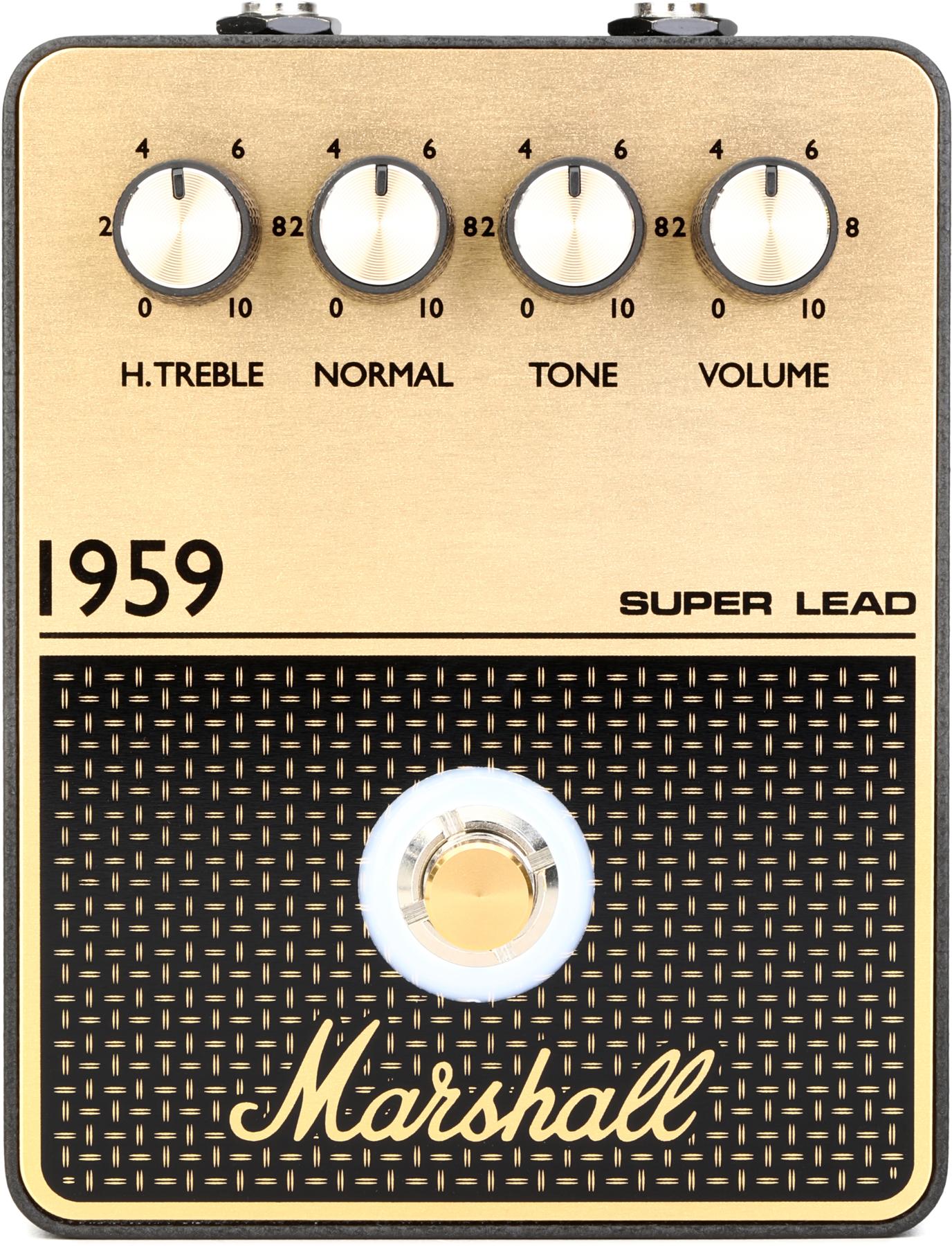

Chelsea Boots Kickin’ With Brit Brawn

One of the beautiful things about the Ruby is how completely it can recolor your amp. Generally speaking, you need a pretty clean amp to achieve the most accurate picture of the Ruby emulation. But even if you want to kick the volume on your amp up into light gain zones, Ruby’s many EQ-shaping tools make the pedal adaptable and capable of retaining its Vox-iness. And even with a black-panel Fender cranked to the point of discernible distortion and compression, the Ruby’s boost, treble, and speaker options can all be used to summon characteristic AC30 sounds to the mix. You can also add focus with the room control by bringing the amp tone right up in your face or adding space, ambience, and a little extra bass ballast from the soft room reflections.

The Verdict

Most efforts to transform an amp by putting a model of another amp in front prove futile. The Ruby ’63 didn’t magically transform my black-panel Fenders to AC30s. But they did make my amps into amazing hybrids that were bristling with unmistakable and thrilling AC30 attributes. I don’t have any newer amps with effects loops, but I’d love to hear how the Ruby ’63 works without a preamp section in the way. At 400 bucks, the Ruby ’63 is expensive, but it seemed transformative enough to feel like another amp entirely. If Ruby can work the same magic for your amp, that 400 bucks could well be a bargain.

Universal Audio Ruby '63 Top Boost Amplifier Pedal

Inspired by the legendary 2 x 12-inch combo amplifier that powered the British invasion, Universal Audio’s Ruby ’63 Top Boost amp pedal is loaded with jangle and bite! This pedal is an end-to-end emulation of one of the most iconic British amps of the ‘60s, sporting Brilliant, Normal, and Vibrato channels that deliver everything from chimey cleans to all-out crunch. Guitarists at Sweetwater are amazed at how closely the Ruby ’63 recreates the sound of a tube amp recorded in a live room, and this life-like quality comes courtesy of UA’s incredible mic, cab, and Dynamic Room Modeling technology. What's more, each pedal in the UAFX series allows you to bypass your amplifier's preamp when the pedal is engaged via the special "4-cable" mode, supercharging your amp with two additional channels.