Many of us have had the experience of picking up someone else’s guitar and feeling instantly at home. But have you ever tried playing your own guitar with someone else’s pick? Unless it has a gauge, shape, and texture similar to your own, an alien pick can make playing even a familiar axe feel like someone changed the locks on your house.

And today, we’ve got more choices than ever—from handmade boutique picks made of unusual organic materials to mass-produced models with closely guarded polymer recipes. Combined, manufacturers produce hundreds of millions of picks every year in a vast array of the aforementioned characteristics.

Yet strictly speaking, picks aren’t necessary. After all, classical guitarists rarely use them, and many players switch between flatpicks and fingerpicking, often in real time, to meet various musical situations. Other players use their fingernails as picks. Some even use coins. Yet aside from the instrument itself, the pick is the universal symbol of guitar playing. How did that happen?

The Spectrum of Plectrums

The story starts at the dawn of recorded history. The word plectrum—which refers to a variety of picks used in everything from guitars to mandolins to harpsichords—comes from Latin by way of the Ancient Greek word plēktron, which, according to Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott’s A Greek-English Lexicon,means “anything to strike with, an instrument for striking the lyre, a spear point.” Ancient Greek artifacts show lyre players holding their plectra, and they’re also mentioned in writings about music from the period. In his book Ancient Greek Music, M. L. West describes how the plectrum was attached to the lyre with a string and had a “handle and a short, pointed blade of ivory, bone, or wood.”

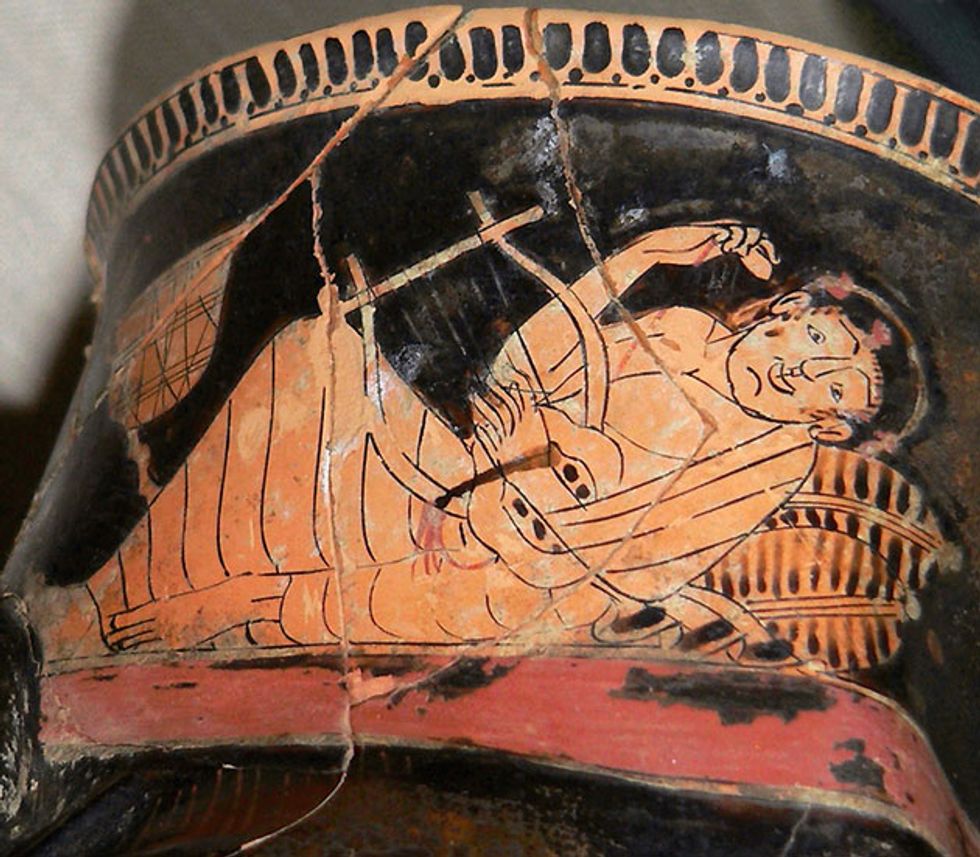

Plectrums have been used to play stringed instruments for more than 2,000 years, as proven by images such as this close-up of a circa-480 BCE Greek drinking vessel depicting a lyre player.

Photo by Peintre de Brygos

Other cultures played stringed instruments with plectrums of different sizes and materials. The Indian sarod, for example, is traditionally played with plectrums made from coconut shells and that look a bit like modern teardrop picks. Others, like the Middle Eastern oud, are played with implements that bear little resemblance to contemporary guitar picks.

According to Will Hoover, author of Picks! The Colorful Saga of Vintage Celluloid Guitar Plectrums, feather quills were the most common material for picking guitars and related instruments until the 19th century, when tortoiseshell became the material of choice. At the time, picks were all handmade, and there were no commercial brands as we know them today.

According to multiple sources cited in this story, Will Hoover’s 1995 book, Picks! The Colorful Saga of Vintage Celluloid Guitar Plectrums, is the definitive source of information on the evolution of the guitar pick over the last century.

The Shell Game

Tortoiseshell—which, once upon a time, was also used for pickguards—had a lot going for it in terms of both sound and feel: Stiff yet flexible, it holds its position and produces a smooth striking surface for the strings. Unfortunately, the “tortoises” contributing the shell—primarily hawksbill sea turtles—were giving up their bodies for more than guitar picks. Overharvesting for everything from combs to furniture adornments and eyeglass frames endangered the turtles’ very existence, and in 1973 it was officially listed as among the world’s most endangered species. Since then, it has been illegal to manufacture picks—or anything else—from tortoiseshell. In fact, to be legal, even old tortoiseshell picks (which are highly prized by collectors) require documentation affirming their antique status.

Further, as Steve Stone put it in a 2008 issue of Vintage Guitar, the forbidden material has plenty of drawbacks, chief among them being that it’s brittle, is easy to chip, and requires a lot of upkeep to maintain smooth edge bevels that don’t get hung up on the strings. “A quarter-sized tortoise pick can end up being dime-sized in a matter of six months of steady polishing and use,” says Stone.

Fortunately, an alternative was found a half-century before tortoiseshell was banned. The modern guitar pick traces its roots to the D’Andrea company, which introduced picks made from celluloid—an early thermoplastic—in early 1922. At the time, the guitar was not yet the musical and cultural icon we know today—both banjo and mandolin were more popular. It’s impossible to know if the guitar would have jumped to the top of the pops without Luigi D’Andrea—the man many regard as the Henry Ford of pick manufacturing—but there’s no disputing that his picks ended up in the hands of countless guitar innovators.

The elder D’Andrea was an unlikely candidate to start the revolution in guitar picking. Born in Foggia, Italy, in 1886, he came to the U.S. in 1902. By the dawn of World War I, he had married and settled with his wife, Flora, in New York City’s Little Italy. According to a company history written by his grandson Tony D’Andrea, Jr., “he eked out a living for his family selling vacuum cleaners to his Italian neighbors in the neighborhood. But Luigi apparently was a pretty driven guy and ready to take full advantage of an opportunity that may come along. And one day it did.”

The plectrum revolution began in the 1920s with the celluloid D’Andrea 351, which is still manufactured in the

company’s Pennsylvania factory. Photo courtesy of D’Andrea

From the Kitchen Table to World Stages

In the 1920s, the Manhattan neighborhoods just north of the financial district were full of factories. The downtown lofts that now serve as homes for well-heeled New Yorkers were sweatshops churning out everything from textiles to machine goods.

“In those days, these small manufacturers would often drag any excess inventory out to the sidewalk in front and display these items for sale,” D’Andrea writes. “One day, walking down a street with many lofts, [Luigi] stopped in front of a company that made ladies’ powder puffs and makeup compacts. With the change in his pocket, he bought the items they had displayed for sale, namely: a few sheets of tortoiseshell-patterned celluloid, several small mallet dies, and the frames of makeup and compact cases and their decoration.”

Back at his apartment, Luigi decided to use the tools and materials to create his own makeup compacts. As he started hammering out heart shapes from the celluloid—a popular decoration for makeup cases at the time—his 8-year-old son Tony noticed the resemblance to the tortoiseshell mandolin picks used by his cousin, Primo. Sensing an opportunity, Luigi brought a box of these heart-shaped picks to a local music store. With Tony, who spoke better English, acting as interpreter, D’Andrea sold the box for $10—over $135 in today’s money, and a tidy sum at the time.

Celluloid—which is still one of the most popular materials for picks—wasn’t exactly new even in 1922. But as Tony Jr. puts it, “it was still the only commercially available plastic in the world … And because of its strength and flexibility and density, [it] made a great guitar pick—and still does.” Made from a combination of nitrocellulose and camphor, celluloid was patented in 1870 by John Wesley Hyatt, who built on the work of Alexander Parkes, a Briton who invented and patented the first thermoplastic, Parkesine, in 1862.

Early 20th-century music catalogs featured mandolin plectrums made from celluloid and shell, often with cork and other design features aimed at improving the player’s grip. One interesting patent had several picks fit together, Swiss Army knife-style, and some picks combined early plastics with rubber, leather, and other materials.

The standardization of the pick—combined with amplification—had an immediate impact on the guitar’s sound and role. “Because striking the guitar strings with a pick produced a much louder sound than could be made with the bare fingers, guitarists in jazz and dance bands had to play with a pick to be heard above the other instruments on the bandstand, like the woodwinds, brass, and drums,” explains Jon Chappell, co-author of the Guitar for Dummies (Wiley) series. “In the 1920s and ’30s, musical styles dictated that guitars replace banjos, so performers like Eddie Lang and Freddie Green became known as guitarists and no longer had to bring a banjo along on their gigs. Green was the guitarist with the Count Basie Band for 50 years and was famous for his signature four-to-the-bar rhythm technique. Essentially, Green would hammer out quarter-note chords, delivered as downstrokes, which served as the foundation of the band’s rhythm, or accompaniment, sound. The pick was also essential for the techniques developed by influential jazzmen like Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt, who took picking into the single-note realm and demonstrated the guitar’s potential as a solo instrument alongside horns and strings. Then there was Les Paul, Barney Kessel, and George Van Eps, as well as country pickers like Jimmy Bryant, who adapted the bowing technique of his days playing violin to master double picking. On the acoustic side, a whole school of high-speed bluegrass playing was developed around the flatpick—it’s even called ‘flatpicking.’”

But picking wasn’t just about speed. “[Highly influential American folk group] the Carter Family used the pick to combine melody and chords in a way that became a template for country and folk,” Chappell says. “And of course, the pick would later give rock players the power and attack that defined the sound of the electric guitar for decades.”

Birth of the 351

Demand grew quickly, and Luigi’s kitchen-table business moved to several factory spaces, including homes in a small building on 29th Street, a larger facility on Long Island, and finally to its current Connecticut-based headquarters and Pennsylvania factory location. And though the company would expand into the businesses of importing instruments and producing accessories, picks have remained its mainstay.

But until D’Andrea’s original epiphany, most picks sold by major companies were made in small shops under contract. Luigi both standardized and industrialized pick making, and by 1928 was mass-producing picks on an unprecedented scale, using semi-automatic punching machines and tumblers to smooth the edges. With input from players, he developed more than 50 celluloid-pick shapes, and dozens more that were available in real tortoiseshell. “I remember being in my grandfather’s office and watching players visit on a Saturday morning to bounce guitar picks on the glass tabletop and discuss the different tonal qualities of celluloid versus real tortoiseshell, and the merits of one shape over another, as the picks bounced,” Tony Jr. says.

Early 20th-century singer-guitarist Nick Lucas, shown in this 1930s image, is considered the performer who first popularized the notion of playing guitar with a pick—specifically the D’Andrea model 351 that most modern designs descended from. Photo by GAB Archive/Redferns

Luigi gave the shapes numbers—which are still in use today. Famous examples include the small, pointy teardrop he called the 358, the larger, rounder teardrop he termed the 354, and the ubiquitous rounded triangle of the 351, which Tony Jr. calls “the standard of the industry [that] still represents the pick of choice for 98 percent of guitar players throughout the world.”

The 351 was originally associated with Nick Lucas, an early 20th-century singer and guitarist regarded by many to be the first to popularize playing the instrument with a plectrum. But long after Lucas faded from the pop charts, the unique traits of the 351 had come to define the average person’s conception of the guitar pick. The latter was aided by the fact that D’Andrea never patented his designs—but most of the competing brands were actually picks designed and manufactured by D’Andrea. That would start to change in the ensuing decades.

Concurrent with development of the pick, the guitar itself was undergoing a rapid evolution in terms of technique, tone, and popularity. As new generations of jazz, country, and pop players expanded its potential as both a lead and a rhythm instrument, the flatpick went from an accompanist’s basic strumming utensil to a precision tool that opened up new realms of speed and accuracy.

Front and back of the Herco Vintage 66—a pick made from nylon, the first material to rival celluloid in popularity.

Photo courtesy of Jim Dunlop

The Name Game

Interestingly, another D’Andrea innovation—printing on picks—would spur an interest in collecting. It started with the D’Andrea brand name, later evolving to include other manufacturers and, most notably, artists. In the 1950s, D’Andrea started making custom picks for manufacturers and players. For example, Fender’s popular pick was actually a rebranded 351.

By the next decade, the pop-music revolution that had started with Elvis was in full bloom—and demand. Pick-manufacturing competition suddenly soared as fans became players and demanded the opportunity to use the equipment their heroes used, right down to the guitar pick. Some of those players became collectors too, prizing picks by classic and new artists, as well as classic examples in both celluloid and tortoiseshell. Ann Pearson, founder of the Vintage Guitar Picks and Things website, has been offering a forum for collectors for years. “It began as a way of cataloguing my personal vintage guitar-pick collection as it grew in size,” she says. “However, I started to realize the need for a place one could go for information about collecting. It’s really the first and only resource of its kind on the net. Daily, I receive various questions from collectors seeking information on guitar picks, and I always make every attempt to answer every question I receive. Even if it's an ‘I’m sorry, I really don’t know’-type of answer.”

Like many of the manufacturers we spoke to for this story, Pearson refers to Will Hoover’s book Picks! as a must-have resource for collectors and anyone interested in the plectrum’s history. As she puts it, “Will created a spark in the darkness for pick collectors.” Other notable collector-historians include Joe Macey and Brian Bouchard, both of whom—like Hoover and Pearson—are contributors to Pick Collecting Quarterly, an online resource for plectrum fanatics worldwide. Though hard to find, Bouchard’s Guitar Picks of Rock & Roll is another important book used by collectors and fans to rate and identify items in their possession.

Like collectors, manufacturers sometimes themselves go to unusual lengths to honor the picking choices of the greats. “Django Reinhardt used a button as a pick,” says D’Andrea’s plant manager Charlie Lusso, who has been watching the pick business evolve since he joined the company in 1981. “At one time, we supplied a vendor with a knockoff of the button he used!”

Rise of “the Big Three”

From the 1950s to the 1980s, pick manufacturing continued to evolve to meet the demand spurred by the wave of baby-boomer guitarists. Along the way, new stylistic developments in both popular music and guitar playing itself spurred new designs and incorporation of new materials.

It was during this time that, says author Will Hoover, D’Andrea faced its first serious competition from the Hershman Musical Instrument Company—better known as Herco. Initially, Herco offered celluloid picks manufactured in Japan. However, the company’s most lasting contribution began in the 1960s, when it offered picks made of nylon, the first material to rival celluloid in decades. The idea originated with Californian Joseph Moshay, but didn’t catch on until Herco brought it to the masses.

Herco and D’Andrea faced competition from Japan, as well, thanks to a company founded by Shoji Nakano—Pickboy—which by the mid 1970s was producing more than 700,000 picks a month.

Though celluloid was more affordable and more popular among players, real tortoiseshell still had its champions. Even before its trade was outlawed in 1973, manufacturers began looking for other synthetics that could mimic the best qualities of shell while simultaneously eliminating some of its disadvantages, such as its brittleness and inconsistency.

Chemical engineer Jim Dunlop started designing musical-instrument accessories in his native Scotland in 1965. Based on reading about player preferences and his own research, Dunlop began making picks out of nylon. Within a few years, he’d left his job at a chemical-engineering company and built a factory in California. By the ’80s, Dunlop would own nylon pioneers Herco, and join D’Andrea and Pickboy in what Hoover calls “the Big Three.”

At the time, electronics were rapidly changing the guitar’s sonic potential. Distortion boxes and higher-gain amps opened guitarists to tones with less emphasis on attack. You no longer had to pick every note to be heard.

Yet at the same time, some rock and fusion players were playing with more precise—and faster—picking techniques than ever before. “Guys like Al Di Meola and, later, Steve Vai pushed the boundaries,” says Lusso, himself an accomplished guitarist. “Then there was the sweep-picking movement of the 1980s—those fast arpeggios. They all influenced how some players choose and use their picks. At the same time, people like David Gilmour and many others showed how different picking techniques could take advantage of the technology to produce a range of sonic textures.”

In addition to nylon, other alternatives to celluloid began appearing. “In 1981, Jim Dunlop discovered Tortex material as an alternative to celluloid,” says Dunlop product manager Frank Aresti. “Pick manufacturers had long been trying to discover a material to achieve the properties of tortoiseshell—at first it was celluloid, then we discovered Tortex. Jim was a machinist by trade, so he also thought to give the picks more precise gauges—in millimeters—than what was typical at the time. [Editor’s note: Prior to that, picks simply came in light, medium, or heavy gauges.] Aresti adds, “Our colors made the picks stand out in the store. Today [Dunlop] picks are made from nylon, Ultem [the thermoplastic polyetherimide], Delrin [another thermoplastic known as polyoxymethylene], graphite, polycarbonate, stainless steel, aluminum, and felt—and we’re always looking at new materials.”

The Many Personalities of the Pick

Although a major identifying point for many players’ preferred picks remains its color—from faux tortoise to solid hues, pearlescent models, and the abstract-impressionist color mix Lusso lovingly refers to as “puke”—it’s the shape, thickness, bevel, and texture that makes a player stick with a particular pick. “We have great players who swear by different models, but it’s interesting to see how the same pick can work in different styles,” Lusso says. “Joe Pass used a 358, but chicken-pickin’ Tele players also use it because its sharp point gives that bright, articulate sound. The bigger 354 teardrop became a favorite for Lee Ritenour and those L.A. jazz guys, but it’s also used by David Gilmour. Pat Metheny uses a thin pick but just uses the rounded edge of it with a close grip.”

All things being equal, a thick pick will produce a faster attack and fatter sound. But, as Lusso notes, many players carry alternatives for specific situations. For instance, many guitarists prefer a light pick to get the shimmery acoustic sound heard on so many pop hits. In fact, between composition, shape, size, and thickness, there is an overwhelming number of ways to shape your tone and technique through use of different picks. And while it’s been decades since the most popular shapes came to be, there’s still plenty of innovation in the industry.

“We make well over a thousand different models,” Dunlop’s Aresti says. “It’s safe to say a great deal of development goes into every pick, but some picks require more than others. Take our Primetone series for example: This is a complicated pick with a great deal of features and benefits that took a lot of time and attention to develop. The grip is the first thing players notice when they pick up the pick, and we were keenly aware of what we wanted the player’s experience to be, so a great deal of time was spent on design for that. The material and the beveled edge are the next things players notice, so we sweat over those details, as well—particularly the bevel, since that is the primary point of contact with the string. A simpler pick, by comparison, would be our new Tortex Flex picks, which we announced at NAMM 2017. We start with the material and spend more time on the finishing process to achieve a certain feel when the pick comes in contact with the strings.”

Today, the majority of mass-produced picks are made using one of two processes: molding—the technique developed for nylon but also used on some plastic-compound models—and punching with tool dies that, Lusso says, resemble cookie cutters. “Once the picks come out of the punch press, they undergo a process called tumbling, which creates both the finished feel and the smooth edges players expect,” says Lusso. “It’s typically a two-step process, with each step taking about a day and a half. So a pick actually takes about a workweek to make. Today, we use such environmentally friendly materials as corn cobs in the tumbling process. The goal is to get that nice beveled edge and finished feel.”

As for new designs, “we’re always getting ideas, both internally and from players,” Lusso says. “Since 2012, we’ve been owned by Delmar Products, Inc., which is the exclusive distributor for celluloid, so we can utilize these resources to develop new and unique designs, too. But we also have an archive of old designs from the 1950s, and we often find that a lot of ‘new’ ideas were tried a long time ago. A design needs to work on a massive level for us to produce it. Making a new pick model is a big investment, and in terms of tooling, it costs us the same to make 200 as it does to make 250,000. Punch dies cost between $5,000 and $10,000, while the molds we use for nylon and Delrin cost tens of thousands of dollars. Our original tooling [for nylon picks] cost over $80,000 back in the 1980s.”

Yet pick making isn’t only about mass production. It continues on a more grassroots level as well, thanks to a new generation of handcrafters who make specialized picks of both traditional and nontraditional materials. “We use a bench grinder that has a grinding wheel on one side and a buffing wheel on the other as the main tool,” says Chris Fahey, founder of boutique outfit Gravity Picks. “The pick is slowly shaped and then buffed to a mirror finish—slow and steady, no magic involved.”

Fahey’s apprenticeship began when he started working with Vinni Smith of V-Picks in 2007. “That is where I initially learned the craft of pick making. Three and a half years of shaping little pieces of plastic will make anyone into a master picksmith. It is tedious, monotonous work. Fortunately, I enjoy that type of work. The inspiration for Gravity Picks came from looking at the other dozen or so handmade pick companies and seeing how I could do something that they weren’t doing.”

Fahey and Smith are part of a growing community of boutique makers. Other notable companies include Wegen, Brossard, Hot-Picks USA, Childs Custom Guitars (which handcrafts picks from wood, mother-of-pearl, and other materials), StoneWorks, BlueChip Picks, and more. Does Fahey see a connection between today’s small shops and the 20th-century pioneers? “I feel that I have a small amount of ingenuity and a lot of tenacity to build upon what others started,” he says. “But the folks that created [the industry] from nothing are in a league of their own.”