The link between guitars

and cars has been discussed

often. Who among us doesn’t

love swoopy sports cars, sick bobber

bikes, or wicked hot rods?

Flashy and loud, brimming with

sex appeal, and plenty of geeky,

mechanical specs to discuss—instruments and vehicles share

many of the same characteristics.

I’ve spent countless weekends at

custom car shows or concours

and vintage races while ogling

fine machinery. Not surprisingly,

I find that parallels exist right

down to the way we personalize

and modify our toys, as well as

the attitudes about doing so.

In the automotive world, performance is what it’s all about. Pumping up the intake pressure with turbos and superchargers to gain horsepower (can you say preamp?), or tuning an exhaust (choosing the right speaker cab) is just the beginning. We like to have controls in easy reach to negotiate tricky twists or turns, and pedals underfoot to jam on the brakes or power through straight passages. As you can see, I’m already letting my worlds collide.

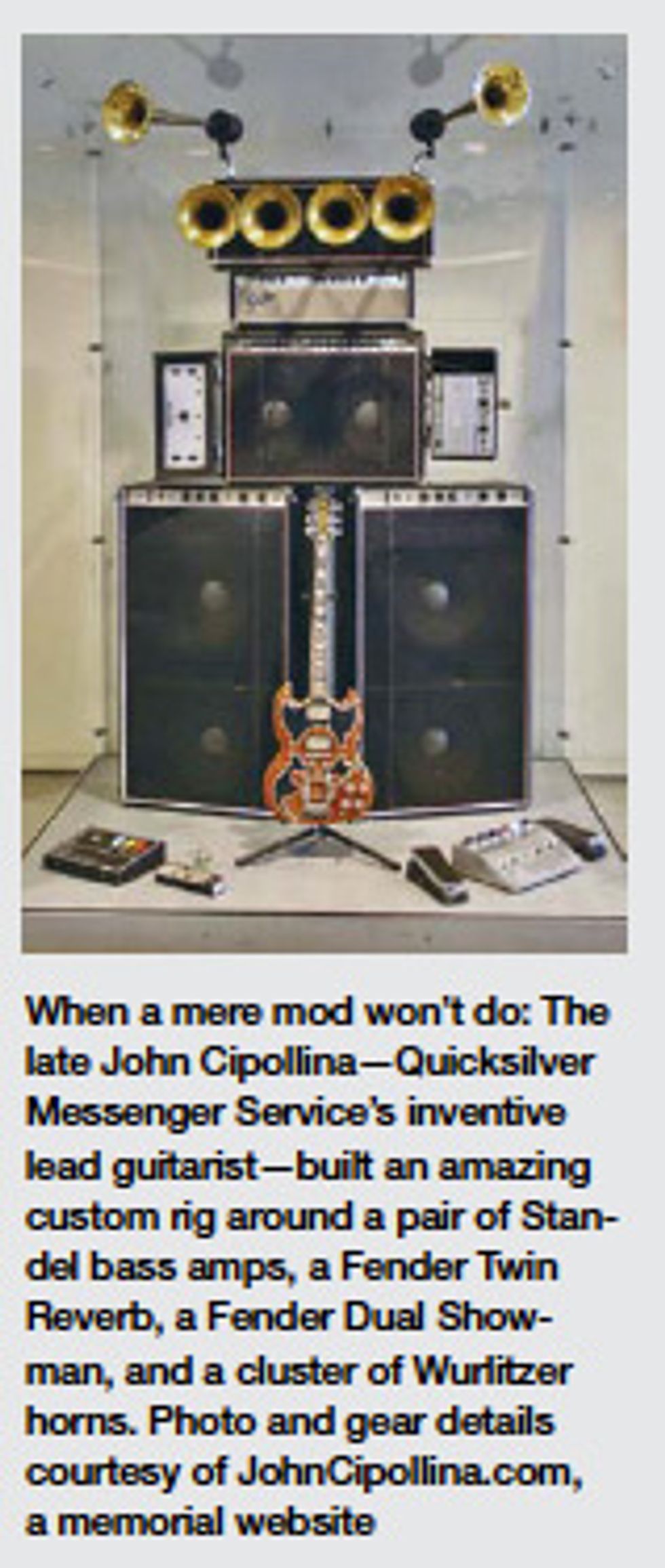

Today, performance mods aren’t considered radical, but almost a right. Everyone wants an edge over the competition, or maybe a little push over the cliff to get one’s creative juices flowing. The game was on when big-band guitarists started stuffing phonograph needles into their guitars. Performance was what Randy Smith had in mind when he created cascading preamp sections for the first Boogies. It’s what Jeff Beck (coincidentally an automobile hot-rodder himself) sought when he removed the covers from his Les Paul humbuckers to get a sonic leg up. Steve Miller and Boz Scaggs heaped extra pickups onto their semi-hollowbodies back in the heyday of Haight-Ashbury. Not to be outdone, Quicksilver’s John Cipollina wove a dozen amps, cabinets, and controls together for his signature sound. A decade later, Edward Van Halen jammed a naked humbucker into his striped, hot-rodded guitar to get the sound he couldn’t buy off-the-shelf. Like dropping a hemi into a ’32 Ford, the replacement pickup is the musical equivalent of a motor transplant—the staple of a hot-rodder’s vernacular.

Playing at your best requires you to be at ease with your instrument. The notes must fall beneath your fingers without difficulty. Similarly, rodders often modify vehicles to provide a pleasing or responsive ride. Even at the beginning of the electric guitar era, the lines were blurred between disciplines. Soon after the whammy bar was invented, Paul Bigsby and Leo Fender began to make tweaks to the design. Bigsby, a motorcycle fabricator himself, created elaborate, raw aluminum tremolo arms reminiscent of his Crocker motorcycle shifters. To improve comfort and fit, Fender curved and scalloped the bodies of the Stratocaster and Jazzmaster until they flowed like the long hoods of European racing cars. Indeed, one such 1960s design was named Jaguar and another, the Mustang, was adorned with racing stripes. Clearly, the pioneers of American electrics understood the relationship between guitars and cars.

Personalization of material property is as old as creation, so why should instruments be immune? From the simple act of applying a sticker to elaborate inlays, engraving, or airbrushing graphics—guitars mimic vehicles in every way. Musicians see themselves as individual snowflakes and there’s no better way to prove it— except playing—than accessorizing guitars. Like jewelry for your axe, there are countless hardware choices. Functional or merely cosmetic, the simple act of replacing a guitar’s knobs, pickguard, or tuners can be a statement of identity similar to aftermarket wheels on a pimped ride.

Some would argue that it’s sacrilege to corrupt a design from its stock configuration. This is a debate that can be heard at car shows as well as vintage guitar festivals. In 1988, for example, a 1973 Porsche 911 was merely a 15-year-old, used, foreign sports car. Then the Miami Vice crowd tore them apart and rebuilt them with bigger motors, sloped noses, fat fender-flares, and giant whale-tail spoilers. Rolling on their ultra-wide, gold-colored wheels, these modified icons of ’80s style can now be had for the cost of an entry-level Toyota. In contrast, had such an example been left in its original form, it could be worth four times that amount—or more.

Similarly, it was common in the ’70s to strip the finish off guitars for a more “natural” appearance. I recall using Zip-Strip to remove the olympic white finish from my early ’60s J bass, reckoning the bare lumber would better complement my band’s earthy vibe. I was personalizing my axe—which was just a $300 used instrument at the time— and the practice was consistent with the trend of the day. I was oblivious to the fact that in both the automotive and instrument world, a time-worn original is worth much more than a restored repaint—even with original parts intact. That Zip-Strip melted thousands of dollars off the J’s future value, but at the time, I was happy in my ignorance.

The choice to modify any possession to make it more distinctive is a personal decision. There are those who have no use for an original 1932 Ford, but would cherish a chopped and channeled rat-rodded version. In turn, a 1956 Strat without a Floyd Rose might be useless to a metal guitarist. Is performance or vanity in the here-and-now more or less important than an uncertain future value? If I had it to do over again, would I have left my bass white?

Jol Dantzig is a

noted designer, builder,

and player who co-founded

Hamer Guitars,

one of the first boutique

guitar brands, in 1973.

Today, as the director of

Dantzig Guitar Design, he continues to

help define the art of custom guitar. To

learn more, visit guitardesigner.com.

Jol Dantzig is a

noted designer, builder,

and player who co-founded

Hamer Guitars,

one of the first boutique

guitar brands, in 1973.

Today, as the director of

Dantzig Guitar Design, he continues to

help define the art of custom guitar. To

learn more, visit guitardesigner.com.

In the automotive world, performance is what it’s all about. Pumping up the intake pressure with turbos and superchargers to gain horsepower (can you say preamp?), or tuning an exhaust (choosing the right speaker cab) is just the beginning. We like to have controls in easy reach to negotiate tricky twists or turns, and pedals underfoot to jam on the brakes or power through straight passages. As you can see, I’m already letting my worlds collide.

Today, performance mods aren’t considered radical, but almost a right. Everyone wants an edge over the competition, or maybe a little push over the cliff to get one’s creative juices flowing. The game was on when big-band guitarists started stuffing phonograph needles into their guitars. Performance was what Randy Smith had in mind when he created cascading preamp sections for the first Boogies. It’s what Jeff Beck (coincidentally an automobile hot-rodder himself) sought when he removed the covers from his Les Paul humbuckers to get a sonic leg up. Steve Miller and Boz Scaggs heaped extra pickups onto their semi-hollowbodies back in the heyday of Haight-Ashbury. Not to be outdone, Quicksilver’s John Cipollina wove a dozen amps, cabinets, and controls together for his signature sound. A decade later, Edward Van Halen jammed a naked humbucker into his striped, hot-rodded guitar to get the sound he couldn’t buy off-the-shelf. Like dropping a hemi into a ’32 Ford, the replacement pickup is the musical equivalent of a motor transplant—the staple of a hot-rodder’s vernacular.

Playing at your best requires you to be at ease with your instrument. The notes must fall beneath your fingers without difficulty. Similarly, rodders often modify vehicles to provide a pleasing or responsive ride. Even at the beginning of the electric guitar era, the lines were blurred between disciplines. Soon after the whammy bar was invented, Paul Bigsby and Leo Fender began to make tweaks to the design. Bigsby, a motorcycle fabricator himself, created elaborate, raw aluminum tremolo arms reminiscent of his Crocker motorcycle shifters. To improve comfort and fit, Fender curved and scalloped the bodies of the Stratocaster and Jazzmaster until they flowed like the long hoods of European racing cars. Indeed, one such 1960s design was named Jaguar and another, the Mustang, was adorned with racing stripes. Clearly, the pioneers of American electrics understood the relationship between guitars and cars.

Personalization of material property is as old as creation, so why should instruments be immune? From the simple act of applying a sticker to elaborate inlays, engraving, or airbrushing graphics—guitars mimic vehicles in every way. Musicians see themselves as individual snowflakes and there’s no better way to prove it— except playing—than accessorizing guitars. Like jewelry for your axe, there are countless hardware choices. Functional or merely cosmetic, the simple act of replacing a guitar’s knobs, pickguard, or tuners can be a statement of identity similar to aftermarket wheels on a pimped ride.

Some would argue that it’s sacrilege to corrupt a design from its stock configuration. This is a debate that can be heard at car shows as well as vintage guitar festivals. In 1988, for example, a 1973 Porsche 911 was merely a 15-year-old, used, foreign sports car. Then the Miami Vice crowd tore them apart and rebuilt them with bigger motors, sloped noses, fat fender-flares, and giant whale-tail spoilers. Rolling on their ultra-wide, gold-colored wheels, these modified icons of ’80s style can now be had for the cost of an entry-level Toyota. In contrast, had such an example been left in its original form, it could be worth four times that amount—or more.

Similarly, it was common in the ’70s to strip the finish off guitars for a more “natural” appearance. I recall using Zip-Strip to remove the olympic white finish from my early ’60s J bass, reckoning the bare lumber would better complement my band’s earthy vibe. I was personalizing my axe—which was just a $300 used instrument at the time— and the practice was consistent with the trend of the day. I was oblivious to the fact that in both the automotive and instrument world, a time-worn original is worth much more than a restored repaint—even with original parts intact. That Zip-Strip melted thousands of dollars off the J’s future value, but at the time, I was happy in my ignorance.

The choice to modify any possession to make it more distinctive is a personal decision. There are those who have no use for an original 1932 Ford, but would cherish a chopped and channeled rat-rodded version. In turn, a 1956 Strat without a Floyd Rose might be useless to a metal guitarist. Is performance or vanity in the here-and-now more or less important than an uncertain future value? If I had it to do over again, would I have left my bass white?

Jol Dantzig is a

noted designer, builder,

and player who co-founded

Hamer Guitars,

one of the first boutique

guitar brands, in 1973.

Today, as the director of

Dantzig Guitar Design, he continues to

help define the art of custom guitar. To

learn more, visit guitardesigner.com.

Jol Dantzig is a

noted designer, builder,

and player who co-founded

Hamer Guitars,

one of the first boutique

guitar brands, in 1973.

Today, as the director of

Dantzig Guitar Design, he continues to

help define the art of custom guitar. To

learn more, visit guitardesigner.com.