It’s probably not too far of a stretch to say that most guitarists at one point have pondered building their own guitar. The definition of “building” can vary from creating a Frankenstein out of several guitars and spare parts to buying a body, neck and electronics and assembling one, to all-out, hand-crafting one from start to finish. Back when I was in high school in the mid-‘80s, I took on my first build by assisting with some of the smaller tasks and handing off those results to the real builder to finish off my guitar. The tasks were basic: planing and cutting the body shape as well as some sanding. Back then there was no Internet, the woodshop class had no templates and information was scarce. Nonetheless, I had been bitten by the builder’s bug. Companies and people were making these instruments and I wanted in! Sadly with my poor woodworking skills and lack of knowledge (and tools) I wrote it off as a pipe dream and settled for watching The New Yankee Workshop and marveling at all those wood clamps Norm had in his shop. The dream was shelved until late 2009.

Several months ago I was reading a copy of Premier Guitar (yes, I read it religiously) and noticed an ad for the Phoenix Guitar Company. Having seen the ad several times before, I looked up their website and found that they were just a couple of miles from my house. I dropped in, introduced myself to the owner, George Leach, and we got to talking. He mentioned that twice a year they (George and his partner Diana Huber) hold a small class that lasts about 15 weeks (every Saturday from 8:30am to 5:30pm) and the 5-6 students build their choice of a variety of acoustic models ranging from nylon string classical to grand auditorium steel string guitars. Intriguing me to no end, I pressed on and found that they were starting the next class in March. After a talk with my editor it was agreed upon that I, Steve, the non-woodworking and mechanically declined was going to build his own guitar…finally. But what kind of teaching method could they use that would make sense to me? How could I actually do this without making a complete mess of a beautiful stack of wood? Was I really going to walk out at the end of class with a playable and quality instrument? These questions all weighed heavily on my mind even though George assured me that everything would work out in the end. As I write this first installment I have already completed six of the Saturdays and am happy to say things are looking really good! Lets back up and I’ll start from Day 1.

Prelude

A month before class began I went into the shop and chose my model and wood types. Since I’d never owned a nice classical guitar it was an easy choice, especially considering I already have a great Taylor GS and ‘50s Gibson J-50. There were several classical models at the shop and after playing each of them I decided to go with a rosewood back and sides, and an Engelmann spruce top. With the woods picked out and the fingerboard width chosen (standard 2” width) I just needed to pick up some ear and eye protection since the Phoenix Guitar Company provided all of the other necessary tools.

Day 1: Sides, Top and Back Preparation

The first day began with introductions to my fellow classmates (Carlos, Tim, Rob, Mike and Don) as well as some background information on the class and how it came to be. Since 2001 they have been teaching two group classes per year and also offer one-on-one classes 2-4 times per year. Diana was actually a student of the first class but has helped teach every one since then. The one-on-one classes take place over the course of a couple of weeks while the group class lasts four months. I was curious as to what type of teaching method they’d use especially since lectures in high school weren’t the best way to get information across to me…I was a lab guy. Fortunately George and Diana read my mind and the class is very hands-on with mini-lectures and demonstrations interspersed to explain the current step. It’s also nice that they put a high degree of importance on shop safety and proper technique because no guitarist wants to lose a finger or a hand!

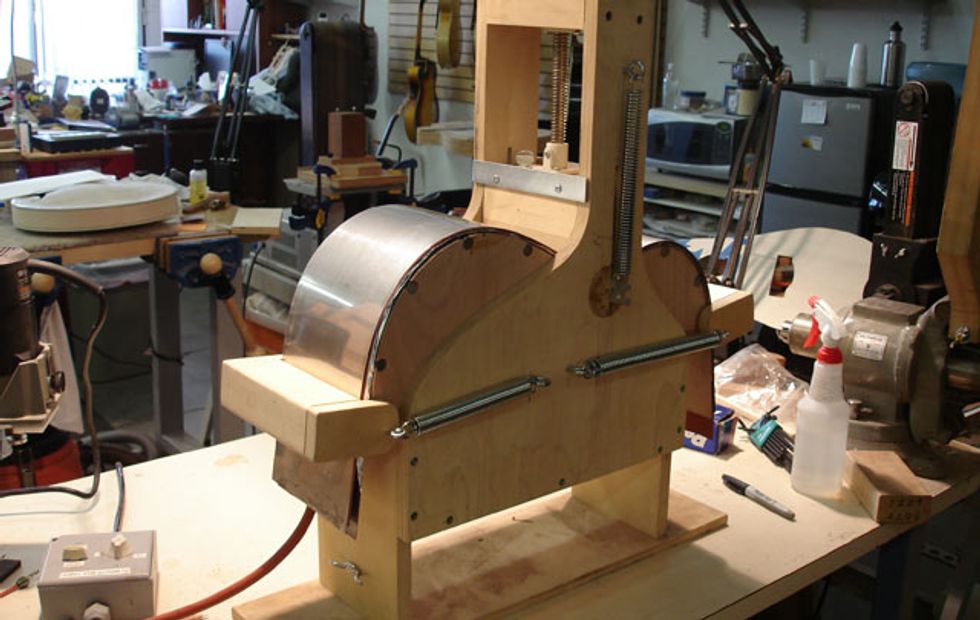

Back to class, we began with bending the sides of the guitar. The process was actually rather simple, or rather made that way by the use of benders and their expertise. We sprayed the rosewood (or mahogany in the case of Don’s guitar) with a water bottle and prepared them for the bender, which is the shape of half of the side of a guitar. With a heating pad on it holding it in place the side was clamped down and set aside for a short period of time. Removing the side from the bender it was put into a wood mold, which also held the previously bent bottom bout. Waxed paper kept the glue from sticking to the mold and spring clamps held the sides in place while we glued on the head and tail blocks.

With the sides drying we took our pre-glued tops (some steps are done ahead of time for expediency) and began working on inlaying the rosettes. In my case the rosette is one piece so George helped out with the tricky step and routed the top to fit and glue it in place. After it dried I spent some time scraping the top to remove any excess glue, then handed the top over to Diana who ran it through the sander to achieve the appropriate final thickness (between .080 to .090). I traced the shape onto the top and made a second line on the outside of the outline and rough-cut the top to shape. With the top ready I used a plexiglass template to trace the bracing pattern onto the wood and began rough cutting my braces.

Onto the back. If there is one thing I’ll take away from this experience it’s that wood glue is incredibly strong and sets a lot faster than you might imagine. With such thin pieces of wood I didn’t expect the glue to hold the back together so easily. Using what looked like three boat dock ties, we put a bead of glue on the back pieces and joined them together with these rope and wood clamps. Within 45 minutes, the back was dry and ready for scraping, thickness sanding and basic shape cutting. After that I cut and glued the back center strip on packed it in for the day…until I realized there was more time available so I moved onto Day 2’s first steps.

Using what are called go-bars (dowels) we supported the sides while still inside the mold to ensure the sides stayed in place during later steps. The next step was to glue the braces onto the top and go-bar them to let dry. With the top laid upside down and each brace glued in one at a time, I used up to three dowels to hold each brace in place. The station that allows this has a piece of heavy plywood held a couple of feet above so the dowels exert a downward pressure on the braces. It wasn’t hard to do but looks really impressive with them all in place. That officially ended my first day.

Day 2: Bracing and Lots of Clamps

The bracing steps were repeated for the back of the guitar. Using the same dowels to hold it in place I left the braces to dry. The next step involved some serious elbow grease to take off the excess wood protruding from the sides of the mold. This is the step that makes the sides the exact thickness and radius they need to be to accept the back and top. Using a scraper tool I spent a good hour taking wood off each side until it was near flush with the mold. Once the rough thickness was correct, the last bit was done using two different sanding wheels that had different radii. For the top it was a flat wheel with no radius, and the back was a 25-foot radius (yes, feet, not inches). Using the heavy wheels made of plywood we basically held them like a bus steering wheel and twisted them back and forth until our chalk lines had disappeared from all edges indicating the side was shaped correctly. This step is both tedious and relaxing because you can let your mind wander a bit while intermittently checking the progress. When that step was finished I repeated the process on the top side.

With the top removed from the go-bar area, the next step was to shape the braces. Shaping comes in the form of carving with a finger plane, chisel and sandpaper. It was explained that the braces needed to taper down to 1/8” at the bottom to allow the top and back to lay flat on the sides. This was where I met my first technical problem, the finger plane. It seemed that no matter what I did that plane just wanted to chew the wood up. Diana came by and showed me the proper technique, but no matter what I did it seemed I was pulling chunks of wood away, so I switched to the sandpaper to dig away a little less aggressively. After some time my braces were scalloped and ready….and my shoulder was sore! I should mention that a few braces needed some super glue to put a chunk back that I had taken out with the chisel. Clearly, I’m not perfect.

The last step of the day was installing the kerf onto the sides of the guitar. Kerf is the surrounding material on the top and back of the sides that gives extra surface area and support to glue the top and back on. This is the step that Norm Abram would be proud of because it uses more clamps than I’ve ever seen in my life. Basically, you lay out 5-6” strips of kerf (made of Engelmann spruce) on each side of the sides and glue and clamp them with finger clamps into place. At any given point I would have around 36 clamps holding the kerf into place while the glue dried. After 10 minutes or so the clamps could be removed and reused on the next piece of kerf.

Day 3: Rough Body Assembly

Day 3 started with removing the ribs from the mold to prepare the top and back to be glued on. After final sanding was done on the kerf (once again using the chalk for reference) the sides were ready. Surprisingly it didn’t take long to glue the top on, but as you can see from the picture we used a lot of clamps again to hold it down. This step was repeated for the back and left to dry.

After the drying was complete I used a router to remove the excess overhang wood on both the top and back exposing what was now a “box” in its basic, final shape. The structural go-bars were then removed from the box by snapping them to fit through the sound hole. In a proud moment I tapped on the guitar to hear it resonate for the first time. I could feel the vibration of the sander across the room coming through the box too…a proud moment!

With the remaining time left in the day I glued the binding onto the sides of the fingerboard (which had already been slotted but not yet radiused). Unfortunately one side of the binding lifted up enough that it needed to be removed. This is where the glue showed its strength and required a heating pad to be applied to loosen up the glue while a tool helped pry it up and off. Unreal, that wood glue. And that wrapped up Day 3.

The Cliff Hanger

Since I’m out of space I’ll need to pick up from Week 4 next time. Suffice it to say I’ve learned a ton about guitar building so far and am extremely surprised that it’s working out so smoothly. Coming from a guy who has a warrant out for his arrest from the hammer police, this is truly a thing of beauty. Tune in next month as I continue my journey into the great world of weekend warrior luthiery.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)