Beginner

Beginner

• Learn how to define a chord inversion.

• Apply inversions to your favorite chord patterns. • Add more interest to your progressions.

• Add more interest to your progressions.

It's easy to fall into the trap of playing chords in the same, predictable way. But if we realize that a chord is just a collection of notes, we can easily and musically change how we stack those notes for new sounds. We call these chord "inversions," because we are… wait for it… inverting the notes in the chord.

In this lesson, I am going to show you how to use inversions to add spice to a few of the most commonly used chord progressions. These shapes are a great tool to help you create and express your individuality and better understand how music works.

Let's take a look at what chord inversions are. As we've stated, they are simply a group of notes rearranged into a different order. With triads–three-note chords consisting of the 1 (or root), 3, and 5–you have three possible inversions: root position, 1st inversion, and 2nd inversion. As the name suggests, root position has the root as the lowest note in the chord, while 1st inversion has the 3 in the bass and 2nd inversion has the 5 in the bass. (When we expand to four-note chords we add the 3rd inversion, with the 7 in the bass.)

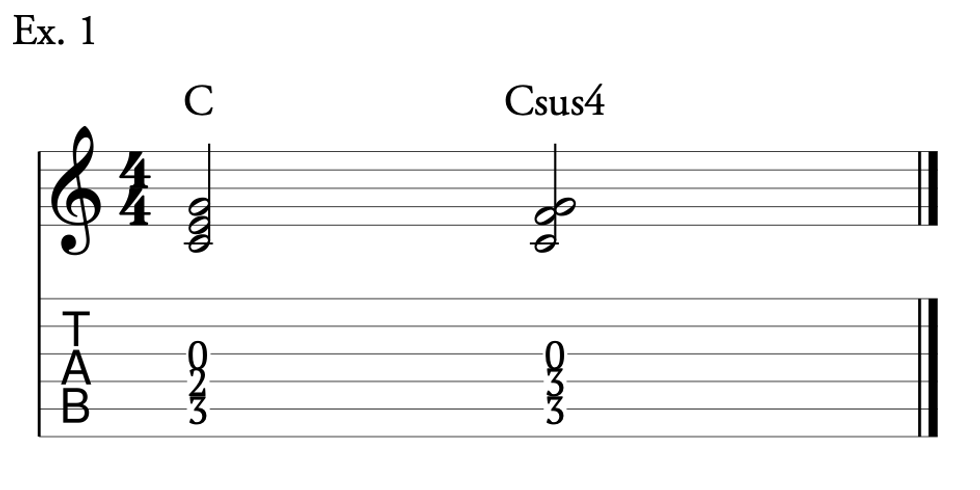

In Ex. 1 you can see the various inversions of a G major triad (G–B–D) and a Gmaj7 chord (G–B–D–F#).

Chord Inversions Ex. 1

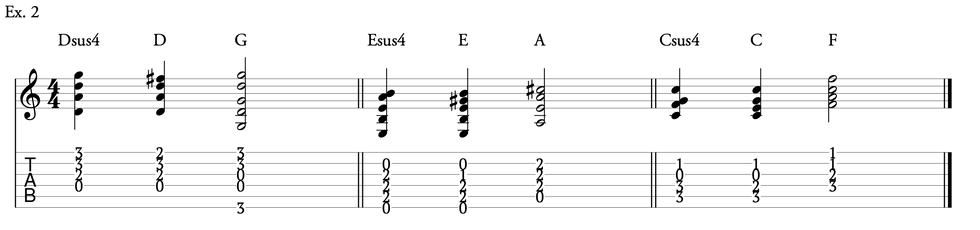

Ex. 2 shows one of the most popular chord progressions in music, G–C–D, or the I–IV–V. I kept the strumming consistent and the fingerings rather easy.

Chord Inversions Ex. 2

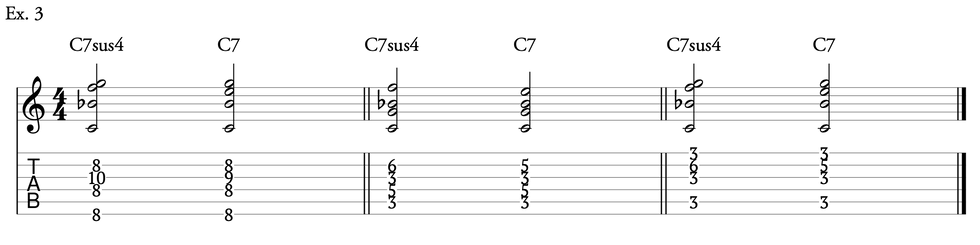

Now that we have our "vanilla" progression, let's use inversions to make it more interesting. In Ex. 3 we insert a G7/B chord, which is 1st inversion, to create a smoother bassline into the C chord in measure 3. The C moves up by a step for the D chord and then I add in a 1st inversion D chord (D/F#) to create a half-step motion to the G.

Chord Inversions Ex. 3

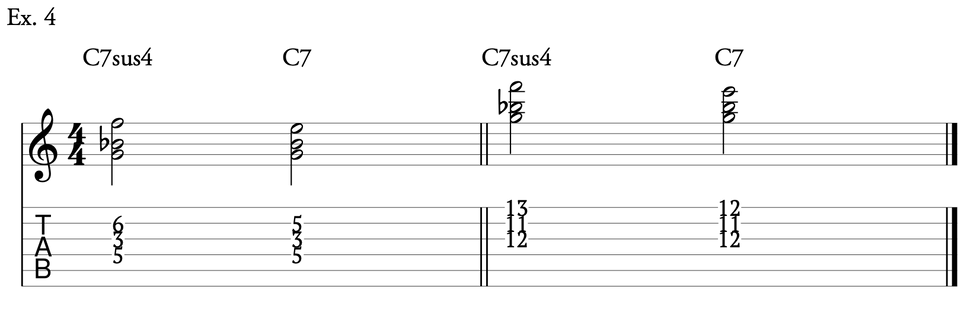

Let's take that bass movement and make it a bit clearer. In Ex. 4 I single out the bass notes. This is a cool way to really add emotional development to your chord progressions. You will notice that I keep the same rhythmic vibe through all of the examples. You can use all of these techniques in different parts of the same song to change the level of intensity.

Chord Inversion Ex. 4

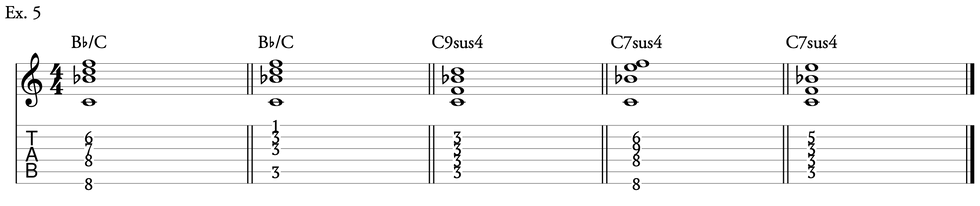

Ex. 5 is based on a minor chord progression. This will be the "vanilla" version that we will then embellish with more inversions. It's a very basic I–IV–IVm progression in A minor. Get comfortable with these shapes before moving on to the next step.

Chord Inversions Ex. 5

In Ex. 6, we add an Am/G, D/F#, and Dm/F to the mix. These inversions allow for a super-hip descending bass line (A–G–F#–F). After playing this one a few times listen to the intro to "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" to see how George Harrison masterfully used inversions.

Chord Inversions Ex. 6

The Beatles - While My Guitar Gently Weeps

As you can see, inversions can be a powerful tool. In Ex. 7, I single out the bass notes again to really bring out that descending movement. You can work on your right-hand picking techniques by playing this example with just the pick, pick and fingers, or just fingers.

Chord Inversions Ex. 7

Ex. 8 is an interesting chord progression because it doesn't fall entirely within a single key. One way to think of the E–A–D–G progression is V–I–IV–bVII in the key of A, although it's notated here in the key of E. This progression has a unique rhythmic signature, where there is a push, or anticipation, on the "and" of beat 4 in measures 1 and 3.

Chord Inversions Ex. 8

Next up is—you guessed it—adding in the inversions. There's so much that you can do with a progression like Ex. 9. In the first measure I added a 1st inversion E (E/G#) as a passing chord to give the bassline a half-step approach going into the A. I repeated the same technique going into the D and G chords.

Chord Inversions Ex. 9

Ex. 10 takes our already interesting chord progression and showcases the bass movement between the chords. The rhythm in this example is a bit more modified but it still retains the most important feature of the pushes on the "and" of beat 4 in every other measure.

Chord Inversions Ex. 10

Don't be afraid to experiment and come up with your own fingerings for chords and inversions. Listen to your favorite players and try to copy what they are doing. You will find that many guitarists use chord inversions to define their style and sound. Cheers.