Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Investigate the blues and jazz influences that were key to Danny Gatton’s style.

• Learn how to mix single-note lines and chord stabs.

• Develop stronger hybrid-picking chops.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

In the previous installment of Beyond Blues, we explored the rhythm guitar techniques of the incredible Danny Gatton. As promised (or perhaps as threatened), we’re back again to investigate some of his crazy lead guitar style.

To create his unique sound, Gatton incorporated influences from many different genres. If you did any research into his vast discography last month, you’ll have noticed a dramatic change in sound from the country twang of his Redneck Jazz Explosion to the more straight-ahead jazz on New York Stories, to the rockabilly edge on Cruisin’ Deuces, or the more blues-based playing on Relentless. There’s no denying that all these years later, no one has truly mastered his style. The best we can hope for is to get our heads around a few of his ideas to bring an edge to our own music.

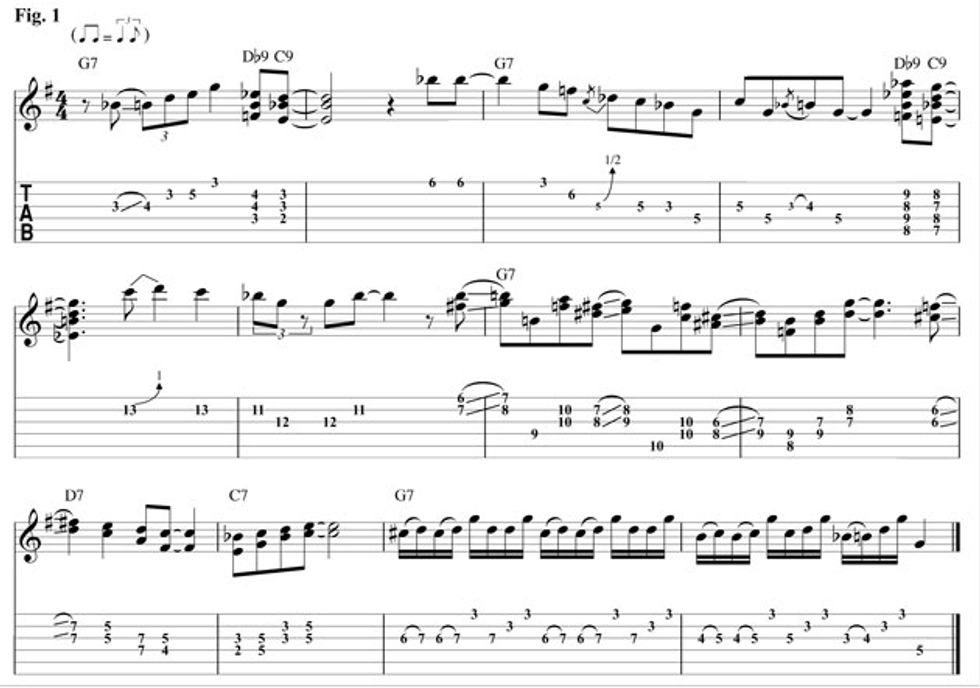

Our first solo (Fig. 1) consists of four basic licks played over a blues in G, each using different ideas. This doesn’t function as a well-balanced solo, it’s more of a “kitchen sink” approach, and Gatton would be more likely to take each of these ideas and develop them over a whole chorus.

The first four measures feature a blend of country-blues phrasing and chord punches to outline the quick change to the IV chord (C7) in the second measure. The descending blues-scale phrase in the third measure is typical of this laid-back blues playing.

The next phrase takes place over the IV chord and is a fantastic idea, even if it’s a little difficult to execute. In the audio example, you’ll hear me do a swell with the tone knob, which creates a wah-like effect—almost like the note is crying. This is extremely tricky to do, perhaps even more on a Telecaster! To pull this off, practice reaching back with your pinky and picking closer to the bridge.

A country influence pops up next where we outline G7, D7, and C7 with double-stops. This may present itself as a bit of a finger twister, but take your time with it and try using it in each of the five CAGED positions I discussed in a previous lesson [https://www.premierguitar.com/articles/Beyond_Blues_Understanding_CAGED_and_the_V_Chord]. If you want to see how far one can take this technique, check out the mind-melting Scotty Anderson, who would play similar ideas at twice this speed while shifting all over the fretboard!

Our final lick in this solo is one of Gatton’s devastating banjo rolls, in which he’d pluck the strings using a combination of flatpick and fingers. These hybrid-picking passages take time to get up to speed. Follow the picking pattern of flatpick–flatpick–middle–flatpick–middle–ring and build up from a slow tempo to something more challenging over a period of time. When playing these, Gatton would approach 200 bpm, so they’re not for those who scare easily.

Our second solo (Fig. 2) is inspired by Gatton’s Redneck Jazz Explosion band and features more jazz-influenced chord changes using a I-VI-IIm-V in place of the more common I-IV-V you hear in simpler blues.

We start off outlining the I and IV chords by fitting a melody around a chord shape. This is a great way to define harmony in a jazz setting, and serious cats like Joe Pass or George Benson do it all the time.

The next phrase comes directly from a Redneck Jazz Explosion solo, and it illustrates how Gatton was more of an “ear” player than a “theory” player. What do I mean by this? Watching his instruction videos or reading past interviews, I’ve never heard Gatton say anything like “I use Super Locrian over this chord” or “I love the sound of Lydian Dominant.” Instead his ear simply prompts him to create some tension in a particular spot, so he plays notes that “shouldn’t work” but actually do the trick.

If you’re curious about what scale you’re hearing, it works like a Dorian mode with an added b5. Over a G7, this loosely implies a G7b5#9.

Over the C7 chord, our perception changes as we begin to use notes from C Mixolydian—C-D-E-F-G-A-Bb. (That Bb is the b7 of C7.) It feels like a series of descending arpeggios, most notably the Dm7 and C major in measure six. For the VI-IIm-V7 chords, we use notes from G minor and G major pentatonic scales (played over E7b9, then Am7 and D7, respectively) to create a sweet-sounding melody to float over the progression.

The final lick outlines a quick I-VI-IIm-V7. It begins on G, descends chromatically to the b9 of E7, then hits four notes that fit into the A Super Locrian before shifting up to the G major pentatonic, and finally ends with some chord stabs.

I hope you’ve enjoyed these two Gatton-inspired lessons as much as I’ve enjoyed toiling over them, and they’ve given you a reason to check out more of his playing and transcribe some new ideas for yourself.