Intermediate

Beginner

• Learn how to use "box" patterns to create licks in different keys.

• Understand how to use open-string drones to create signature parts.

• Hone your ability to play melodic slide-guitar textures.

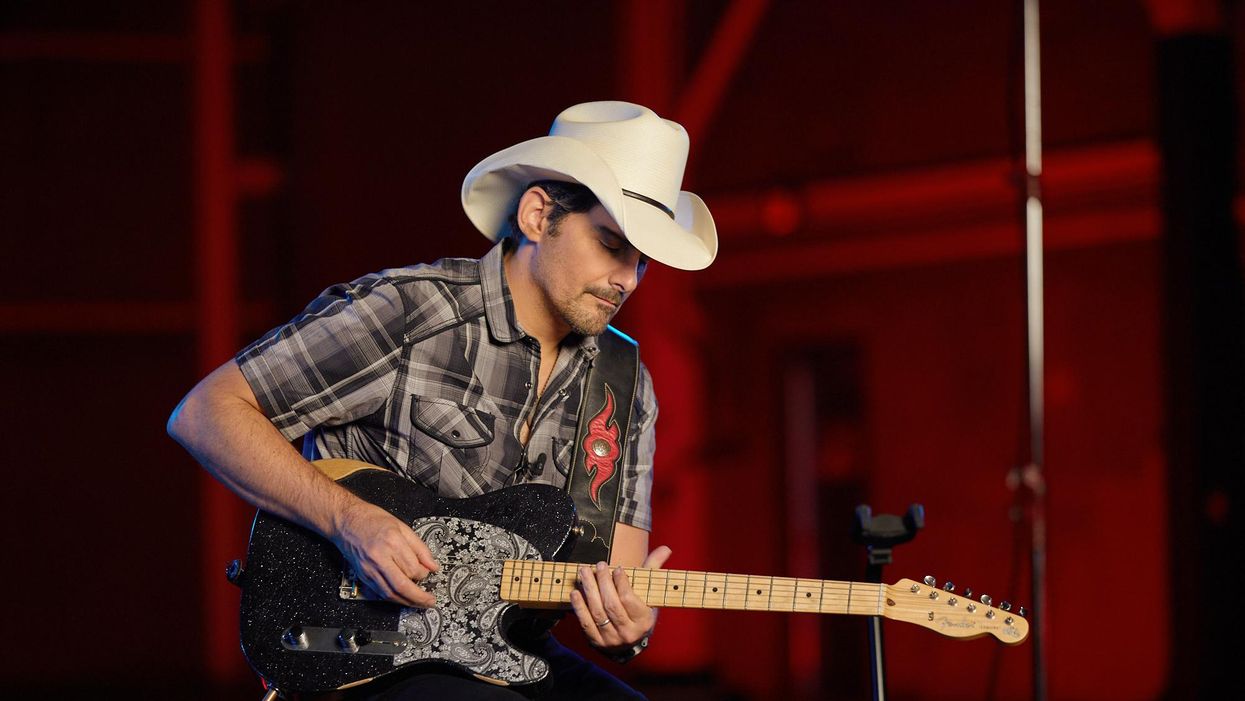

I feel a little embarrassed when people ask me about my guitar influences. I can't claim expertise of Hendrix, I haven't spent hours woodshedding Eric Johnson, and I couldn't tell you the first thing about how to play like David Gilmour. My influences are more behind the scenes, lurking in the shadows of the music industry. They don't have big names, but they are monster players. I'm talking about the number one, most honest influence on my guitar playing: Nashville session guitarists.

In case you don't know, Nashville session guitarists are the cream of the crop—they have to be. Their job is to listen to a song once, write a chart for it during that single listen, step out onto the tracking room floor and simultaneously create, react, and execute a guitar part at a radio-perfect level in one take. I've figured out some tricks by studying the work of musical sharpshooters like J.T. Corenflos, Kenny Greenberg, and Tom Bukovac, and now I get to apply it in my own career when I'm called in for a session. Now, let's steal some tricks.

“Kiss You in the Morning" Box

An important thing to remember throughout this lesson is that the goal is to sound perfect. A dead note on your guitar solo should not be the reason that one of your fellow session players is late to pick up his daughter, so this is no time for finger tapping or seven-fret stretches. I call this the "Kiss You in the Morning" box because it's similar to the signature lick in Michael Ray's song of the same name.

You want the song to sound good, which means you need to sound comfortable. That's why this pattern (Ex. 1) is a great home base for your chord-based riffing. This is a segment of a diagonal major pentatonic scale that only uses your first and third fretting-hand fingers. You don't have to stretch or remember complicated patterns, and it's almost impossible to sound bad here. Place your first finger on the chord's root, which falls on either the low 6th or 5th string, and slide your third finger up two frets to access the rest of the pentatonic notes. It's a closed shape, so you can move it all over the fretboard to whatever key or chord you need, which comes in handy when you're scanning down a Nashville number-style chart in real time and having to come up with a hook or rhythmic motif.

The “All About Tonight" Box

This one is a little tougher, but more rewarding. I could do an entire session just using this box and rearranging the notes in different ways to make my melodies and textures fit the mood of the song. You can hear hints of this pattern in Blake Shelton's "All About Tonight." This is a natural extension to the previous example, but in Ex. 2 we start to introduce double-stops (playing two notes at a time). Low notes on the lower strings sound thick on their own, but as you move up the neck it's a good idea to start using double-stops if you want to keep the guitar sounding thick. In this box, your first finger is always in charge of the same fret, and your third finger oversees hammer-ons two frets higher. To play the double-stops I'm talking about, barre the 5th and 4th strings with your first finger and pick them. Then hammer on the 5th string with your third finger. Boom. You can do the same trick with different string sets.

Open for Business

You've got some lead chops built up, but somebody will be singing for 90 percent of the song, so what do you do? In keeping with our rule that we want our playing to sound comfortable, the answer is open chords. Full barre chords give you a lot of strings to keep track of, and if your dynamics, sustain, and muting aren't spot on, then the producer is going to have to hire someone to redo your parts after you leave, and that doesn't bode well for your session career.

Throw on a capo because only five keys are generally acceptable for playing guitar in a session: G, D, E, C, and A. Is the song in Db? Put a capo on the 1st fret and play in C. How about F#? Place a capo on the 2nd fret and play in E. Even if a song is in A, 95 percent of the time the acoustic guitar player will opt to play with a capo on the 2nd fret so he or she can move around comfortably in the key of G. Ex. 3 shows some of the special open chords that session players use all the time.

Palm-Muting Verses

Wide-open chords aren't everything, though. Songs need to have structure and flow, and the band members need to be on the same page about where the song is going. If you watch a session with guitarists Derek Wells and Jerry McPherson both playing guitar, they aren't clashing. They both know how energetic the song needs to be at any given moment. Chances are you'll nail it if you play the verses a little lower in energy and the choruses a little higher in energy. You can palm-mute the lowest two strings of an open chord, or you can palm-mute a power chord, or you can palm-mute thirds that fit inside of the chord. Check out Ex. 4 for an example. Any of those routes will work to get you from the intro to the chorus. And when it comes time to do a "fill" at the end of the measure or progression, all you really need to do is unmute what you're already doing! Fish in a barrel.

My Kinda Drones

"Box" playing is great, but I'm sure you want to have more than just boxes in your toolkit. One of the best tricks for coming up with melodies that don't sound boxy is by using what I call "My Kinda Party" drone lines. The signature lick in Jason Aldean's song, "My Kinda Party," is a wonderful example of this. Come up with a melody and play the whole thing on the 2nd string. Don't get too complicated, and don't make it too fast. Make it a nursery rhyme, a simple, hummable jingle that a drunk Bonnaroo crowd could sing back to you.

To allow the 1st string to ring out as you move along the neck, you need to fret the notes on the 2nd string using the very end of your fingertips. Now pick through both the top two strings while sliding from note to note (Ex. 5). This adds thickness and texture to the melody and helps make it sound like music, so someone like super-producer Justin Niebank doesn't have to spend time adding effects to your guitar to fill out the mix. As with the open chords, make sure you have the capo in the right spot so the open 1st string fits the song's key.

Get Low

The opposite of that approach is using a technique found in Luke Bryan's tune, "We Rode in Trucks." With this trick, you place the root of the chord on one of the lower three strings and build your melody on the string above it (Ex. 6). My favorite application of this is when you hammer-on to a 3, which puts your hand right in the "All About Tonight" box we talked about earlier if you need to launch into a solo. This trick can only be done if one or more of the low open strings works with the song's key, so you'll have to do some quick mental math and capo accordingly.

Swell into It

This technique is one of the physically easiest to perform, but requires some mental energy to get right. Sometimes the song needs an ambient volume swell to hold things together over chord changes, and this requires choosing your notes carefully. Let's say the progression is Em–C–G–D, with two chords per measure. Look for the notes that both chords share in each measure. Em and C both share E and G notes; G and D both share D notes.

That's the safe route, but you can also swell into notes or pairs of notes that challenge the chord a little bit and make an extension out of it. Swelling into a D over the Em and C turns them into Em7 and Cadd9, respectively, both very cool sounds. And G to D is a pretty strong chord change in this key, so you'll probably want to stick the landing and end up on chord tones here. To change things up from just a D note you can swell in a pre-bent G note and let it down to an F# when the D chord comes in. Or do the same thing, but pre-bend a B note and let it fall to an A (Ex. 7). You can nail this approach if you know your chord tones. Note: You'll need a good amount of delay and reverb to make the most of your swells. Most players do this with a volume pedal, but with the right guitar—a Strat, for example—you can also accomplish this manually.

High Extensions

Now that we're in the mindset of thinking about what our notes do to the chords we're playing over, adding higher extensions can introduce complexity and texture to a song. I have fond memories of sitting with a friend in high school, both of us holding acoustic guitars, and playing different triads and double-stops over each other's open chord strums—just to hear how one person's triad could affect the other person's chord.

The idea is that you'd pick notes that might not be within the basic triad and use these additions to alter the song's principle chords. If a bass player plays a C, and the acoustic guitar plays an open C chord, and the other electric guitarist plays a C power chord, but you play a B and D double-stop high on the fretboard you just made the entire band sound like a Cmaj9 chord, which is really pretty sounding. If you pick G and Bb, then you made the band sound like a C7 chord, which is bluesy and sarcastic sounding. Session players know what note extensions to add to chords, what these extensions will sound like, and when it's appropriate to use them. Ex. 8 illustrates how to use this trick over a basic progression.

Simple Slidin'

On most sessions, slide is used for texture and not for Derek Trucks- or Sonny Landreth-inspired shredding, so it's mostly limited to chord tones and a couple of simple lines. It is a very cool color, though, and it's well worth learning how to navigate a melody with a slide on your pinky. Slide sounds more like a human vocal than fretted notes, so this technique can really lend itself to making memorable, catchy, singable hooks. This is part of the reason guitarist Rob McNelley is on so many records—he's able to really make slide sing. Just be very careful about not letting strings ring unless you want them to. To come up with a simple, catchy, single-note slide line that soars over the arrangement, tap into the same melody-creating brain space you used for the "My Kinda Party" example, as well as the chord knowledge required for swells and extensions. Chord tones are always safe, extensions can be really cool, and make sure you stick the landing (Ex. 9).

Dot … Dot … Dot

You made it all the way to Ex. 10, so give your brain a break and let a pedal do all the work. Delay is a powerful effect, and when you sync that delay to the song tempo, the pedal can play notes for you. If you see guitarist Justin Ostrander doing something simple, chances are there's a timed delay happening to carry the simplicity. A dotted-eighth is equal to three 16th-notes, and a dotted-eighth delay means once you play a note, that note will come around again three 16th-notes later. And if the repeats are turned up, it'll keep repeating every three 16th-notes to create a cool syncopated feel (Ex. 10).

If you play something completely straight against the syncopated pattern the delay will be creating, the delay fills in the notes between what you're playing and makes an otherwise boring figure sound incredibly interesting. To make this trick work, you'll need a delay with programmable or tap tempo. For best results, tap the tempo for quarter-notes, play eighth-notes, and have the delay set for dotted-eighth-notes.

These guitarists stay mostly out of the spotlight, but with the growing world of media they are starting to get a little more exposure with great programs like Premier Guitar's Rig Rundown with Kenny Greenberg (shown below) or Zac Childs' Truetone Lounge episode with Derek Wells.

Videos like these let you inside the world of the pro session player, and are great resources for learning more from the best in the business. Next time you hear some tasty guitar on a radio hit, you'll know it's tasty for a reason and you're one step closer to being the guitarist who gets to play it.