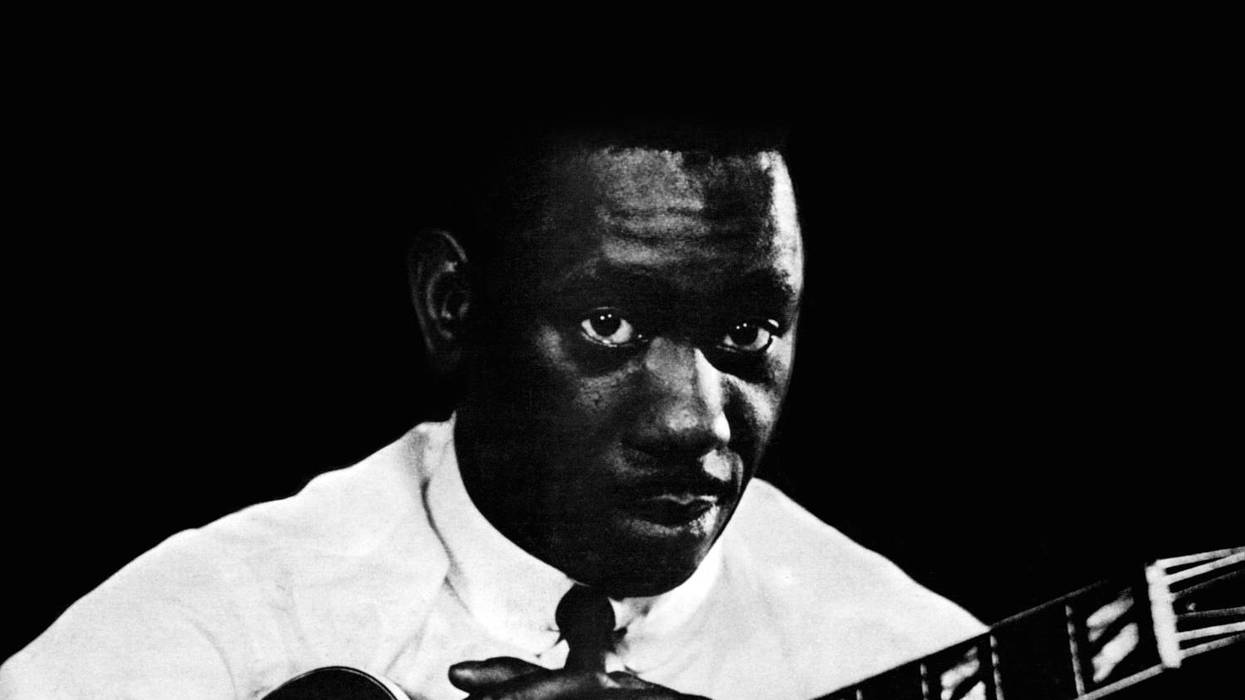

To spawn a completely new musical genre, a musician needs to be unique, technically groundbreaking, and extraordinarily gifted. The virtuosic Gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt (1910-1953) was such a figure. Throughout his teens Django paid his dues accompanying musette accordionists in the dance halls of Paris on violin, banjo, and guitar. Tragically, Django’s promising musical career was nearly ended when his left hand was severely scarred in a caravan fire. Fortunately, the pull of music was so strong that against all odds he retrained himself to play guitar using only his two uninjured left-hand fingers.

During his convalescence, Django discovered jazz, and it subsequently became his lifelong passion. His brilliant recordings with the Quintette du Hot Club de France forged a uniquely European style of jazz that drew inspiration from Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, as well as French musette and Hungarian Gypsy music.

Although Django’s music influenced nearly every other jazz guitarist after him, the only musicians to maintain the pure Django style were the Sinti Gypsies of France, Germany, and the Benelux countries. It was this group of musicians that gave the genre its name. From Django’s death until the 1990s, performances of Gypsy jazz outside the Gypsy community were relatively rare. The immense talent of such contemporary Gypsy guitarists as Boulou Ferré, Stochelo Rosenberg, and Biréli Lagrène was mostly unrecognized until a recent revival that has brought increased awareness to this wonderful style. Gypsy jazz is now flourishing not only in Europe, but also in North America, Japan, Australia, and even further afar.

One of the more distinguishing features of Gypsy jazz is the infectious accompaniment style known as la pompe. This rhythm, which literally means “the pump,” allows a guitarist to provide a complete harmonic and rhythmic foundation for the music. Although Django and subsequent Gypsy guitarists have used a variety of swing and Latin rhythms, la pompe remains the preferred accompaniment style. Therefore, mastery of this rhythm is absolutely essential for learning Gypsy jazz.

The la pompe rhythm is deceptively simple and widely misunderstood. Because la pompe has a heavy accent on beats 2 and 4, beginners often mistake it for a two-beat polka or Western swing rhythm, but la pompe has numerous subtleties that set it apart from these and other styles.

There are several important elements that distinguish la pompe from the American-style “flat four” rhythm playing. First, there’s a very subtle upstroke preceding beats 1 and 3. This is done very quickly no matter what the tempo is. The upstroke seems to be an imitation of a drummer’s hi-hat rhythm. It’s really a grace note, so its time value is not relative to the overall tempo of the song. In Clip 1 you can hear a simple example of la pompe.

To play this rhythm authentically, you must learn the correct right- and left-hand motions. The right-hand is by far the most important, so we’ll start with that. Make sure you’re using proper Gypsy-style right-hand technique with a floating wrist and relaxed pick grip. Play a small upstroke on the bass strings a fraction of a second before the first and third beats. At this point, don’t worry about chord shapes, just mute the strings and play along with a metronome. Don’t let the pick travel very far after you’ve cleared the low 6th string.

Immediately follow the upstroke with a downstroke on the bass strings only. This downstroke should fall right on the first beat of the measure. Next raise your hand all the way to the top of the lower bout of the guitar, and then let it fall to play a strongly accented downstroke on the second beat. This second downstroke should fall predominantly on the treble strings, and it’s crucial to make this motion very large. You should be using gravity, not your muscles, to generate the necessary power. Repeat this process for the remaining two beats in the measure.

The left hand uses precisely timed muting to achieve a rhythmic, drum-like effect. Start by selecting any chord you’re comfortable with, preferably one that uses five or six strings. Begin by pressing down and fretting the chord slightly so that both the downstroke and its preceding upstroke are not muted. Mute with your left hand immediately after the downstroke on beat 1. Now press the chord down so it sounds when you play the large downstroke on beat 2. Finally, mute with your left hand immediately after beat 2’s downstroke.

Beginners usually make two common mistakes: If your upstrokes are too loud and slow, it creates a galloping effect that doesn’t swing. Also, use a very large arm motion on the downstrokes to keep them from sounding weak.

Although it may seem simple at first, it takes a lot of focused practice to master la pompe. A few attempts at playing this rhythm should give you some appreciation of those who’ve mastered it. Nous’che Rosenberg of the Rosenberg Trio can play this rhythm solidly at tempos in excess of 300 bpm for five minutes or more.

To give you a sense of this style, I’ve compiled a number of exercises that are characteristic of the types of ideas Django used in his solos. Before I continue, be aware that Gypsy jazz has a much more systematic approach to technique than most contemporary jazz guitar styles. Because Gypsy jazz was mostly transmitted via oral tradition to successive generations of Gypsies, approaches to picking, improvising, and accompaniment have become highly standardized. Most of these techniques were originally used by Django and have remained part of the genre because of their effectiveness and musicality. The musical examples I will be using in this lesson will reflect the traditional way of playing this genre. Because of this, you’ll often see fingerings and picking techniques that directly contradict contemporary jazz guitar wisdom. Although much of Django’s music can be executed using a more conventional technique, this typically creates a distinct shift in tone, phrasing, and articulation. These differences are especially noticeable when playing on an acoustic instrument.

Django used the rest stroke system, as do nearly all other Gypsy guitarists. This style of picking is ideally suited for the acoustic guitar because it allows one to achieve volume, tone, and speed without uncomfortable tension or pain. In a nutshell, Django’s right-hand technique is a flatpick version of the commonly used classical and flamenco guitar technique known as apoyando. The pick version of this technique has all the benefits of the fingerstyle rest stroke: a secure feeling of placement, reduced muscle tension, and a loud, full tone. In addition, the Gypsy rest stroke takes advantage of basic principles of physics by using the weight of the hand instead of the muscles to propel the pick in much the same manner as a hammer falls on a nail. This stroke is completed by letting the pick come to rest on the next adjacent string, hence the name. For more detailed instruction on learning the rest stroke technique, check out my book, Gypsy Picking.

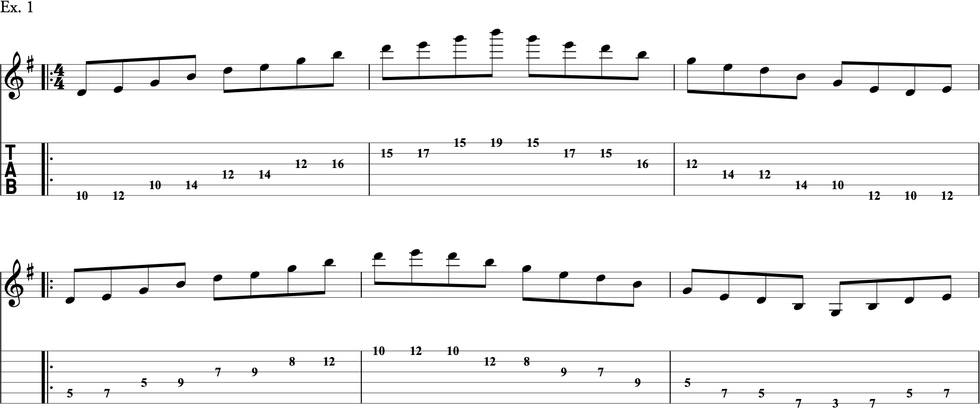

One of the defining characteristics of Django’s style was his heavy reliance on arpeggios. Ex. 1 shows a C6/9 arpeggio pattern that starts on the 7 (B) and concludes with a typical Gypsy flourish. To sound authentic, pay close attention to the fingering and picking indications.

Click here for Ex. 1

Django had a strong tendency to emphasize the 6 and 9 chord tones (in the key of C, that’s A and D, respectively). These tones are only mildly dissonant, but since they are outside of the basic triad they help to create some harmonic interest. The 6/9 sound, both major and minor, is a hallmark of Gypsy jazz guitar.

When Django played minor scale passages, he often used the Dorian mode (1–2–b3–4–5–6–b7) to achieve the minor 6/9 sound. For example, Ex. 2 illustrates using D Dorian (D–E–F–G–A–B–C) over a Dm6/9. Notice how both the 6 (B) and the 9 (E) are emphasized in the second measure. Remember: The rules of alternate picking don’t apply here so much. Check out that last measure.

Click here for Ex. 2

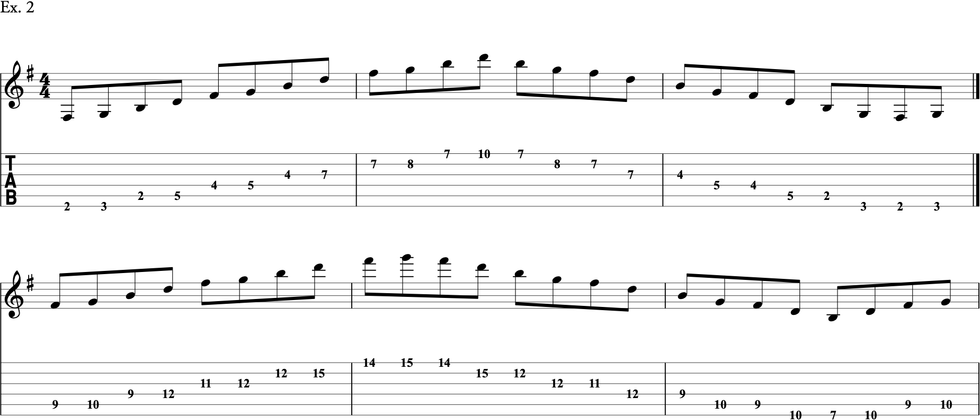

Obviously, you can’t get by sticking only with scales or arpeggios. The subtle art of creatively combining these could fill an entire lesson on its own. Django was an absolute master at this, and Ex. 3 is a slightly longer version of what he might play over a Cm9–Gm9 progression. A Cm6 arpeggio (C–Eb–G–A) appears at the end of the first measure, while a sneaky first inversion Gm triad slips in at the end of the third measure. It’s tricks like these that make Django’s lines so inventive.

Click here for Ex. 3

When playing over dominant chords, Django relied on the Mixolydian mode (1–2–3–4–5–6–b7). Mixolydian differs from the major scale in that the 7 is lowered by a half-step. Ex. 4 demonstrates a G Mixolydian (G–A–B–C–D–E–F) run that links to a Cmaj7 arpeggio (C–E–G–B). Again, we’re always combining scales with arpeggios to break things up.

Click here for Ex. 4

Django also frequently employed the bebop scale when playing over dominant chords. Regular use of the bebop scale coincided with the bebop era of the 1940s, hence its name. However, its existence can be traced as far back as Louis Armstrong’s 1927 solo on “Hotter than That.” Django was heavily influenced by Armstrong and used this scale often. The bebop scale adds an extra passing tone so that chord tones will fall on the strong beats. The passing tone occurs between the b7 and root.

This scale places the root, 3, 5, and b7 on the beat. These chord tones make up the basic structure of a dominant chord and therefore are the strongest target notes. Ex. 5 shows how Django used this scale over an A7 resolving to D6.

Click here for Ex. 5

The harmonic minor scale (1–2–b3–4–5–b6–7) was an integral part of Django’s sound. The scale is identical to the natural minor (1–2–b3–4–5–b6–b7), with the exception of a raised 7 scale degree that strongly resolves to the tonic chord. Although Django would occasionally use the harmonic minor over a minor chord, he mostly used it to achieve altered sounds over dominant chords. Ex. 6 demonstrates how he would use D harmonic minor (D–E–F–G–A–Bb–C#) to move from A7b9 to Dm.

Click here for Ex. 6

Django also made extensive use of the diminished arpeggio (1–b3–b5–bb7). Since each note is the same distance from its neighbors, any note of the chord can be considered the root.

Django used these devices to take advantage of the b9. A simple rule to remember: Play a diminished arpeggio based a half-step above the root of the dominant chord you want to play over. In our example, we use a Bb diminished arpeggio over A7. That yields Bb, C#, E, and G (in other words, the b9, 3, 5, and b7, relative to A7). Ex. 7 demonstrates this in context over an A7b9–Dm6/9 progression.

Click here for Ex. 7

Diminished arpeggios also offer a great way to incorporate chromatic embellishments. In Ex. 8, we move from D7b9 to Gm7 with a triplet-based run full of outside notes. This line leads into a somewhat standard D7b9 arpeggio before resolving to the b3 (Bb) of Gm7.

Click here for Ex. 8

Django also favored targeting chord tones with enclosures. The idea is simple: Just play a note above and below a chord tone before landing on it. Ex. 9 is a quick look at this technique in the key of G. Django often used this pattern to achieve a lightning-fast double-time effect.

Click here for Ex. 9

Ex. 10 demonstrates a series of ascending arpeggios, an idea Django often used. This particular version works well over “Rhythm Changes”-style chord progressions. The chord symbols above the music are the most literal interpretation, and are only one way to describe the harmony. You’ll find that this idea works equally well over numerous other chord progressions.

Click here for Ex. 10

To internalize the most essential parts of the Gypsy style, it’s absolutely essential you do a lot of careful listening. Most Django fans own his recording of “Minor Swing” from 1937. (Head over to the online version of this article to download a backing track for this tune.) Study it carefully, as it’s an excellent example of pre-war la pompe. I often suggest to my students that they listen to some of the numerous duet recordings of Django with various soloists. Since they are duets, you can hear Django’s rhythm quite well. Keep in mind that Django used many advanced rhythmic variations on these recordings, so it’s up to you to pick out the parts where he’s playing straight la pompe.