Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Understand the “three over

four” principle.

• Create angular lines over a

blues progression.

• Learn the dangers of raising

ostriches.

Johnny Cash was attacked by an ostrich. It was his own ostrich. In recalling the incident, Johnny theorized that the ostrich was angry over the loss of its mate, which had died from a bout of cold weather— several of the ostriches that Johnny was keeping on his property were frozen as well. Johnny also claims that he only survived the attack because he happened to be wearing a particularly large leather belt.

I feel so normal after hearing a story like this. I have no ostriches on my property, and my belt is not imposing in any way.

I’m sure that Johnny wasn’t trying to be outrageous or showy by owning ostriches. I’m guessing that he just wanted to have some around, so he went out and got them. Similarly, I’m not trying to be outrageous or showy by using my pinky to reach the notes in the example on the following page. I just like these notes, so I go out and look for them. Sometimes the pinky is the first to arrive, so I let it grab a note here and there. If you give your pinky some exercise, it will serve you well. Just keep it out of cold weather.

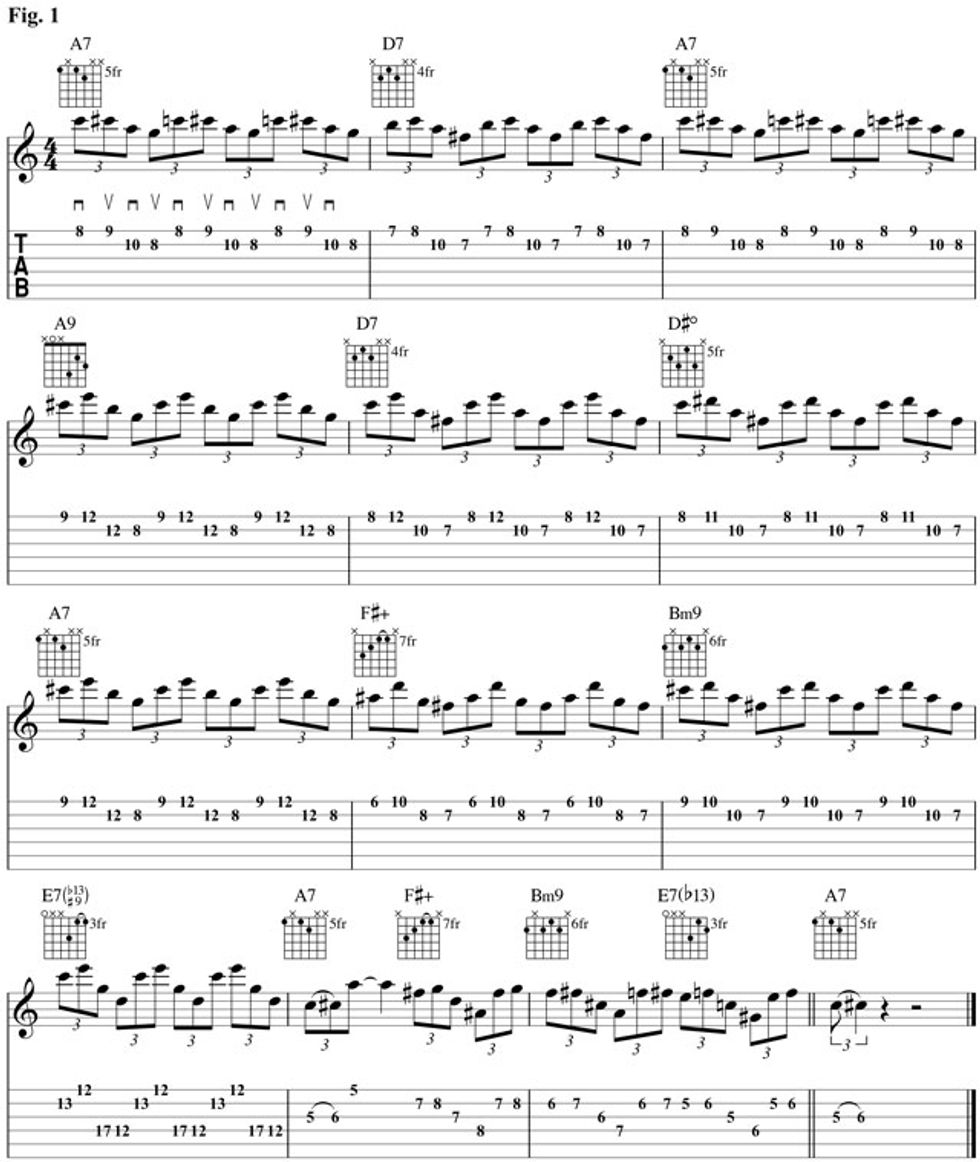

This month’s example is a simple blues progression in A, with a few extra chords thrown in. But for a rock ’n’ roll guitarist like me, those extra chords such as D#dim7, F#+, Bm9, and various altered E7 chords can be as formidable as facing an ostrich charge. My only defense is to practice and listen, and practice and listen even more, getting my fingers and ears around these sounds. I like these sounds, so that’s why I go through the trouble.

The solo pattern is built from two notes going up, followed by two notes going down. To simplify, just think: two up, two down. Soloists often play a lot of notes in one direction, so I like how this phrase reverses so often. It keeps the ear interested.

This is also a good workout for alternate picking. I recommend starting with a downstroke followed by an upstroke, and just keeping that pattern going. For the left hand, I’ve written out the details with tablature to show you where you can find the notes on the neck. Measure 10 is definitely the craziest pinky-stretching and stringskipping moment of the piece. There are other possible fingerings for these notes, but I think this is the easiest one to keep the notes sounding clear.

Rhythmically, I want you to notice that the “two notes up, two notes down” phrase equals a total of four notes. When I see a four-note phrase, my knee jerk reaction is to play 16th-notes. But here, I decided to do something different. I looped the phrase a few times in order to get 12 notes. A phrase of 12 breaks into groups of three just as easily as it does into four, so now I have the option of playing triplets. And that’s what I did. The nice thing is that each time the phrase loops, the notes fall across the beat in unpredictable ways. I’ve heard drummers refer to this technique as “four over three,” and drummers are always good people to learn from.

For the chords, I should mention that the voicings that I’ve chosen often rely on the thumb to play bass notes on the sixth string. I once had a student who looked at me indignantly, and said, “But isn’t the thumb FORBIDDEN?” In response to him—and to all those who avoid the thumb—I would like to officially unforbid it. I heartily encourage you to reach over the top of the neck and hold down some nice, big bass notes. Hendrix did it. Why not give it a try?

And if you are out belt shopping, I’d go with the big one.